Monitoring the Elections and Electoral Fraud 12 ■■DOCUMENTATION Election Results 14 Elections Results and Turnout in Comparison 15

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

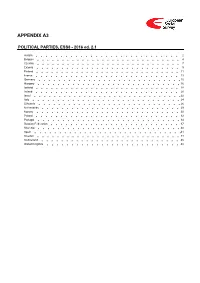

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

INTERNATIONAL ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION Russian Federation – Presidential Election, 18 March 2018

INTERNATIONAL ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION Russian Federation – Presidential Election, 18 March 2018 STATEMENT OF PRELIMINARY FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS The 18 March presidential election took place in an overly controlled legal and political environment marked by continued pressure on critical voices, while the Central Election Commission (CEC) administered the election efficiently and openly. After intense efforts to promote turnout, citizens voted in significant numbers, yet restrictions on the fundamental freedoms of assembly, association and expression, as well as on candidate registration, have limited the space for political engagement and resulted in a lack of genuine competition. While candidates could generally campaign freely, the extensive and uncritical coverage of the incumbent as president in most media resulted in an uneven playing field. Overall, election day was conducted in an orderly manner despite shortcomings related to vote secrecy and transparency of counting. Eight candidates, one woman and seven men, stood in this election, including the incumbent president, as self-nominated, and others fielded by political parties. Positively, recent amendments significantly reduced the number of supporting signatures required for candidate registration. Seventeen prospective candidates were rejected by the CEC, and six of them challenged the CEC decisions unsuccessfully in the Supreme Court. Remaining legal restrictions on candidates rights are contrary to OSCE commitments and other international standards, and limit the inclusiveness of the candidate registration process. Most candidates publicly expressed their certainty that the incumbent president would prevail in the election. With many of the candidates themselves stating that they did not expect to win, the election lacked genuine competition. Thus, efforts to increase the turnout predominated over the campaign of the contestants. -

Public Opinion and Democracy In

PUBLIC OPINION AND DEMOCRACY IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE (1992-2004) by Zofia Maka A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science and International Relations Summer 2014 © 2014 Zofia Maka All Rights Reserved UMI Number: 3642337 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3642337 Published by ProQuest LLC (2014). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 PUBLIC OPINION AND DEMOCRACY IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE (1992-2004) by Zofia Maka Approved: __________________________________________________________ Gretchen Bauer, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Political Science and International Relations Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ James G. Richards, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Julio Carrion, Ph.D. -

Redalyc.POLAND's FOREIGN and SECURITY POLICY

Revista UNISCI ISSN: 2386-9453 [email protected] Universidad Complutense de Madrid España Bieczyk-Missala, Agnieszka POLAND’S FOREIGN AND SECURITY POLICY: MAIN DIRECTIONS Revista UNISCI, núm. 40, enero, 2016, pp. 101-117 Universidad Complutense de Madrid Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=76743646007 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Revista UNISCI / UNISCI Journal , Nº 3 9 ( Enero / January 2016 ) POLAND’S FOREIGN AND SECURITY POLICY: MAI N DIRECTIONS Agnieszka Bieńczyk - Missala 1 University of Warsaw Abstract : This article tries to present the main areas of Polish foreign and security policy.Poland’s membership in the EU and in NATO was the strongest determinant of its position in international relations, and the guiding light of its foreign policy. Poland’s wor k in the EU was focused in particular on EU policy towards its eastern neighbours, common energy policy and security issues, while in NATO, Poland has always been a proponent of the open doors policy and has maintained close relationship with the US, suppo rting many of its policies and initiatives . Keywords : Poland, European Union Security and Defence, NATO, Poland´s bilateral relations . Resumen : El artículo presenta las principales áreas de la política exterior y de seguridad de Polonia, siendo su pertenencia a la Unión Europea y la OTAN los principales determinantes de su posición en las relaciones internacionales y el foco que ilumina su política exterior. -

Download Directly from the Website

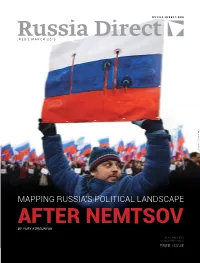

RUSSIA-DIRECT.ORG |#20 | MARCH 2015 © ILIA PITALEV / RIA NOVOSTI © ILIA PITALEV BY YURY KORGUNYUK AVAILABLE FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY FREE ISSUE Mapping Russia’s political landscape afteR neMtsov | #20 | MaRcH 2015 EDITor’s noTE The murder of opposition politician Boris Nemtsov fundamentally changed the landscape of Russian politics. In the month that has passed since his murder, both Western and Russian commentators have weighed in on what this means – not just for the fledgling Russian opposition movement, but also for the Kremlin. What follows is a comprehensive overview of the landscape of political Ekaterina forces in Russia today and their reaction to Nemtsov’s murder. Zabrovskaya The author of this Brief is Yury Korgunyuk, an experienced political ana- Editor-in-Chief lyst in Moscow and the head of the political science department at the Moscow-based Information Science for Democracy (INDEM) Foundation. Also, we would like to inform you, our loyal readers, that later this spring, Russia Direct will introduce a paid subscription model and will begin charging for its reports. There will be more information regarding this ini- tiative on our website www.russia-direct.org and weekly newsletters. We are thrilled about this development and hope that you will support us as the RD editorial team continues to produce balanced analytical sto- ries on topics untold in the American media. Keeping the dialogue be- tween the United States and Russia going is a challenging but important task today. Please feel free to email me directly at [email protected] -

Ukraine by Oleksandr Sushko and Olena Prystayko

Ukraine by Oleksandr Sushko and Olena Prystayko Capital: Kyiv Population: 45.5 million GNI/capita, PPP: US$8,970 Source: The data above are drawn from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators 2015. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Electoral Process 3.25 3.00 3.00 3.50 3.50 3.50 3.75 4.00 4.00 3.50 Civil Society 2.75 2.75 2.75 2.75 2.75 2.75 2.75 2.75 2.50 2.25 Independent Media 3.75 3.75 3.50 3.50 3.50 3.75 4.00 4.00 4.25 4.00 National Democratic Governance 4.50 4.75 4.75 5.00 5.00 5.50 5.75 5.75 6.00 6.00 Local Democratic Governance 5.25 5.25 5.25 5.25 5.25 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.50 Judicial Framework and Independence 4.25 4.50 4.75 5.00 5.00 5.50 6.00 6.00 6.00 6.00 Corruption 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 6.00 6.00 6.25 6.00 Democracy Score 4.21 4.25 4.25 4.39 4.39 4.61 4.82 4.86 4.93 4.75 NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s). -

The 2015 CSO Sustainability Index for Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia

The 2015 CSO Sustainability Index for Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia Developed by: United States Agency for International Development Bureau for Europe and Eurasia Technical Support Office (TSO), Democracy and Governance (DG) Division TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................................................................ ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................ 1 2015 CSO SUSTAINABILITY INDEX SCORES ......................................................................................................... 11 ALBANIA ........................................................................................................................................................................................................ 12 ARMENIA ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... 21 AZERBAIJAN ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 32 BELARUS ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Russian Federation

Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights RUSSIAN FEDERATION STATE DUMA ELECTIONS 19 September 2021 ODIHR NEEDS ASSESSMENT MISSION REPORT 31 May-4 June 2021 Warsaw 25 June 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................ 1 III. FINDINGS ....................................................................................................................... 4 A. BACKGROUND AND POLITICAL CONTEXT ....................................................................... 4 B. LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND ELECTORAL SYSTEM .............................................................. 5 C. ELECTION ADMINISTRATION ........................................................................................... 6 D. VOTING TECHNOLOGIES ................................................................................................. 7 E. VOTER REGISTRATION .................................................................................................... 7 F. CANDIDATE AND PARTY REGISTRATION ......................................................................... 8 G. ELECTION CAMPAIGN ..................................................................................................... 9 H. PARTY AND CAMPAIGN FINANCE .................................................................................. 10 I. MEDIA ......................................................................................................................... -

Federation Without Federalism Relations Between Moscow and the Regions

49 FEDERATION WITHOUT FEDERALISM RELATIONS BETWEEN MOSCOW AND THE REGIONS Jadwiga Rogoża NUMBER 49 WARSAW APril 2014 FEDERATION WITHOUT FEDERALISM RELATIONS BETWEEN MOSCOW AND THE REGIONS Jadwiga Rogoża © Copyright by Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia / Centre for Eastern Studies Content editors Adam Eberhardt, Marek Menkiszak Editor Halina Kowalczyk CO-OPERATION Anna Łabuszewska, Katarzyna Kazimierska Translation Jadwiga Rogoża CO-OPeration Jim Todd GraPhic design Para-buch PHOTOGRAPH ON COVER Shutterstock DTP GroupMedia MAPS Wojciech Mańkowski Publisher Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia Centre for Eastern Studies ul. Koszykowa 6a, Warsaw, Poland Phone + 48 /22/ 525 80 00 Fax: + 48 /22/ 525 80 40 osw.waw.pl ISBN 978-83-62936-43-4 Contents KEY POINTS /5 INTRODUCTION /8 I. POST-SOVIET NEGOTIATED FEDERALISM /10 II. THE LANDSCAPE AFTER CENTRALISATION /13 III. A MULTI-SPEED RUSSIA /18 IV. FERMENT IN THE REGIONS /29 V. MONOCENTRISM STRIKES BACK /34 VI. PROSPECTS: DECENTRALISATION AHEAD (BUT WHAT KIND OF DECENTRALISATION?) /41 MAPS /44 KEY POINTS • The territorial extensiveness of the Russian Federation brings about an immense diversity in terms of geographic, economic and ethnic features of individual regions. This diversity is reflected by serious disparities in the regions’ levels of development, as well as their national identity, civic awareness, social and political activity. We are in fact dealing with a ‘mul- ti-speed Russia’: along with the economically developed, post-industrial regions inhabited by active communities, there are poverty-stricken, in- ertial regions, dependent on support and subsidies from the centre. Large cities, with their higher living standards, concentration of social capital, a growing need for pluralism in politics and elections characterised by competition constitute specific ‘islands of activity’ on Russia’s map. -

ESS8 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS8 - 2016 ed. 2.1 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Czechia 7 Estonia 9 Finland 11 France 13 Germany 15 Hungary 16 Iceland 18 Ireland 20 Israel 22 Italy 24 Lithuania 26 Netherlands 29 Norway 30 Poland 32 Portugal 34 Russian Federation 37 Slovenia 40 Spain 41 Sweden 44 Switzerland 45 United Kingdom 48 Version Notes, ESS8 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS8 edition 2.1 (published 01.12.18): Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. ESS8 edition 2.0 (published 30.05.18): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Spain. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2013 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ), Social Democratic Party of Austria, 26,8% names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP), Austrian People's Party, 24.0% election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), Freedom Party of Austria, 20,5% 4. Die Grünen - Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne), The Greens - The Green Alternative, 12,4% 5. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ), Communist Party of Austria, 1,0% 6. NEOS - Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum, NEOS - The New Austria and Liberal Forum, 5,0% 7. Piratenpartei Österreich, Pirate Party of Austria, 0,8% 8. Team Stronach für Österreich, Team Stronach for Austria, 5,7% 9. Bündnis Zukunft Österreich (BZÖ), Alliance for the Future of Austria, 3,5% Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

The Revenge of the Nation: Political Passions in Contemporary Poland

THE REVENGE OF THE NATION POLITICAL PASSIONS IN CONTEMPORARY POLAND ▪ AZILIZ GOUEZ REPORTREPORT NO. NO. 116 117 ▪ ▪NOVEMBER JANUARY 20192018 ISSN 2257-4840 #POLAND THE REVENGE OF THE NATION POLITICAL PASSIONS IN CONTEMPORARY POLAND AZILIZ GOUEZ ASSOCIATE RESEARCH FELLOW, JACQUES DELORS INSTITUTE AZILIZ GOUEZ TABLE OF CONTENTS Aziliz Gouez is an anthropologist by training, with an interest in issues of identity, memory and political symbolism. Between 2013-2017 she was the Chief Speechwriter for the President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins. As a Research Fellow at the Jacques Delors Institute from 2005 to 2010 she directed a research Executive summary 5 programme on the predicaments of European identity in the post-1989 era, looking in particular at the discrepancy between economic integration, East-West migration of labour and capital on the one hand, Introduction 7 and political and cultural patterns on the other. Aziliz is a graduate of Sciences Po Paris, the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales and the 1. Social policy for good people 10 University of Cambridge. She has lived and worked in Romania, Poland, Ireland, the former-Yugoslavia, as well as the United States and Israel. Recently, she has published on the consequences of Brexit for 1.1 The 2018 local elections and the battle for the Polish province 10 Ireland; she currently steers a project on populism for the Dublin-based IIEA while also contributing to the development of the network of Pascal Lamy Chairs of European anthropology. 1.2 “Good change”: redistribution, family and the active state 13 1.3 “We are not servants, we aspire to more” 16 2. -

ESS6 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

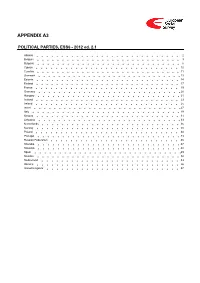

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS6 - 2012 ed. 2.1 Albania 2 Belgium 3 Bulgaria 6 Cyprus 10 Czechia 11 Denmark 13 Estonia 14 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Israel 27 Italy 29 Kosovo 31 Lithuania 33 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 43 Russian Federation 45 Slovakia 47 Slovenia 48 Spain 49 Sweden 52 Switzerland 53 Ukraine 56 United Kingdom 57 Albania 1. Political parties Language used in data file: Albanian Year of last election: 2009 Official party names, English 1. Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë (PS) - The Socialist Party of Albania - 40,85 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Partia Demokratike e Shqipërisë (PD) - The Democratic Party of Albania - 40,18 % election: 3. Lëvizja Socialiste për Integrim (LSI) - The Socialist Movement for Integration - 4,85 % 4. Partia Republikane e Shqipërisë (PR) - The Republican Party of Albania - 2,11 % 5. Partia Socialdemokrate e Shqipërisë (PSD) - The Social Democratic Party of Albania - 1,76 % 6. Partia Drejtësi, Integrim dhe Unitet (PDIU) - The Party for Justice, Integration and Unity - 0,95 % 7. Partia Bashkimi për të Drejtat e Njeriut (PBDNJ) - The Unity for Human Rights Party - 1,19 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Socialist Party of Albania (Albanian: Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë), is a social- above democratic political party in Albania; it is the leading opposition party in Albania. It seated 66 MPs in the 2009 Albanian parliament (out of a total of 140). It achieved power in 1997 after a political crisis and governmental realignment. In the 2001 General Election it secured 73 seats in the Parliament, which enabled it to form the Government.