Poland: Background and U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poland (Mainly) Chooses Stability and Continuity: the October 2011 Polish Parliamentary Election

Poland (mainly) chooses stability and continuity: The October 2011 Polish parliamentary election Aleks Szczerbiak [email protected] University of Sussex SEI Working Paper No. 129 1 The Sussex European Institute publishes Working Papers (ISSN 1350-4649) to make research results, accounts of work-in-progress and background information available to those concerned with contemporary European issues. The Institute does not express opinions of its own; the views expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the author. The Sussex European Institute, founded in Autumn 1992, is a research and graduate teaching centre of the University of Sussex, specialising in studies of contemporary Europe, particularly in the social sciences and contemporary history. The SEI has a developing research programme which defines Europe broadly and seeks to draw on the contributions of a range of disciplines to the understanding of contemporary Europe. The SEI draws on the expertise of many faculty members from the University, as well as on those of its own staff and visiting fellows. In addition, the SEI provides one-year MA courses in Contemporary European Studies and European Politics and opportunities for MPhil and DPhil research degrees. http://www.sussex.ac.uk/sei/ First published in March 2012 by the Sussex European Institute University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton BN1 9RG Tel: 01273 678578 Fax: 01273 678571 E-mail: [email protected] © Sussex European Institute Ordering Details The price of this Working Paper is £5.00 plus postage and packing. Orders should be sent to the Sussex European Institute, University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton BN1 9RG. -

The Image of Poland in Russia Through the Prism of Historical Disputes

THE IMAGE OF POLAND IN RUSSIA THROUGH THE PRISM OF HISTORICAL DISPUTES Report based on a public opinion poll carried out by the Levada Center in Russia for the Centre for Polish-Russian Dialogue and Understanding Warsaw 2020 Report on public opinion research THE IMAGE OF POLAND IN RUSSIA THROUGH THE PRISM OF HISTORICAL DISPUTES Report based on a public opinion poll carried out by the Levada Center in Russia for the Centre for Polish-Russian Dialogue and Understanding CENTRE FOR POLISH-RUSSIAN DIALOGUE Warsaw 2020 AND UNDERSTANDING Report on public opinion research THE IMAGE OF POLAND IN RUSSIA THROUGH THE PRISM OF HISTORICAL DISPUTES Survey: Levada Center Analyses and report: Łukasz Mazurkiewicz, Grzegorz Sygnowski (ARC Rynek i Opinia) Commentary: Łukasz Adamski, Ernest Wyciszkiewicz © Copyright by Centrum Polsko-Rosyjskiego Dialogu i Porozumienia 2020 Graphic design and typesetting: Studio 27 (www.studio27.pl) Cover photo: Lela Kieler/Adobe Stock ISBN 978-83-64486-79-1 Publisher The Centre for Polish-Russian Dialogue and Understanding 14/16A Jasna Street, 00-041 Warsaw, Poland tel. + 48 22 295 00 30 fax + 48 22 295 00 31 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.cprdip.pl Contents Commentary 4 Introduction – background and purpose of the study 8 Information about the study 9 Detailed findings 11 Summary 26 www.cprdip.pl 3 THE IMAGE OF POLAND IN RUSSIA THROUGH THE PRISM OF HISTORICAL DISPUTES Commentary By pursuing their particular, excessive ambi- peace in Europe, and of anti-semitism. Putin tions it was the politicians in interwar Poland played down to vanishing-point the totalitarian who submitted their nation, the Polish nation, to character of the USSR, its tactical coopera- the German war machine and generally contrib- tion with the Third Reich in destroying peace in uted to the outbreak of World War II. -

Flash Reports on Labour Law January 2017 Summary and Country Reports

Flash Report 01/2017 Flash Reports on Labour Law January 2017 Summary and country reports EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate DG Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion Unit B.2 – Working Conditions Flash Report 01/2017 Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). LEGAL NOTICE This document has been prepared for the European Commission however it reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://www.europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017 ISBN ABC 12345678 DOI 987654321 © European Union, 2017 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Flash Report 01/2017 Country Labour Law Experts Austria Martin Risak Daniela Kroemer Belgium Wilfried Rauws Bulgaria Krassimira Sredkova Croatia Ivana Grgurev Cyprus Nicos Trimikliniotis Czech Republic Nataša Randlová Denmark Natalie Videbaek Munkholm Estonia Gaabriel Tavits Finland Matleena Engblom France Francis Kessler Germany Bernd Waas Greece Costas Papadimitriou Hungary Gyorgy Kiss Ireland Anthony Kerr Italy Edoardo Ales Latvia Kristine Dupate Lithuania Tomas Davulis Luxemburg Jean-Luc Putz Malta Lorna Mifsud Cachia Netherlands Barend Barentsen Poland Leszek Mitrus Portugal José João Abrantes Rita Canas da Silva Romania Raluca Dimitriu Slovakia Robert Schronk Slovenia Polonca Končar Spain Joaquín García-Murcia Iván Antonio Rodríguez Cardo Sweden Andreas Inghammar United Kingdom Catherine Barnard Iceland Inga Björg Hjaltadóttir Liechtenstein Wolfgang Portmann Norway Helga Aune Lill Egeland Flash Report 01/2017 Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................. -

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth As a Political Space: Its Unity and Complexity*

Chapter 8 The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as a Political Space: Its Unity and Complexity* Satoshi Koyama Introduction The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita) was one of the largest states in early modern Europe. In the second half of the sixteenth century, after the union of Lublin (1569), the Polish-Lithuanian state covered an area of 815,000 square kilometres. It attained its greatest extent (990,000 square kilometres) in the first half of the seventeenth century. On the European continent there were only two larger countries than Poland-Lithuania: the Grand Duchy of Moscow (c.5,400,000 square kilometres) and the European territories of the Ottoman Empire (840,000 square kilometres). Therefore the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was the largest country in Latin-Christian Europe in the early modern period (Wyczański 1973: 17–8). In this paper I discuss the internal diversity of the Commonwealth in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and consider how such a huge territorial complex was politically organised and integrated. * This paper is a part of the results of the research which is grant-aided by the ‘Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research’ program of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science in 2005–2007. - 137 - SATOSHI KOYAMA 1. The Internal Diversity of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Poland-Lithuania before the union of Lublin was a typical example of a composite monarchy in early modern Europe. ‘Composite state’ is the term used by H. G. Koenigsberger, who argued that most states in early modern Europe had been ‘composite states, including more than one country under the sovereignty of one ruler’ (Koenigsberger, 1978: 202). -

James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 474 132 SO 033 912 AUTHOR Parker, Franklin; Parker, Betty TITLE James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 18p.; Paper presented at Uplands Retirement Community (Pleasant Hill, TN, June 17, 2002). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Authors; *Biographies; *Educational Background; Popular Culture; Primary Sources; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *Conversation; Educators; Historical Research; *Michener (James A); Pennsylvania (Doylestown); Philanthropists ABSTRACT This paper presents an imaginary conversation between an interviewer and the novelist, James Michener (1907-1997). Starting with Michener's early life experiences in Doylestown (Pennsylvania), the conversation includes his family's poverty, his wanderings across the United States, and his reading at the local public library. The dialogue includes his education at Swarthmore College (Pennsylvania), St. Andrews University (Scotland), Colorado State University (Fort Collins, Colorado) where he became a social studies teacher, and Harvard (Cambridge, Massachusetts) where he pursued, but did not complete, a Ph.D. in education. Michener's experiences as a textbook editor at Macmillan Publishers and in the U.S. Navy during World War II are part of the discourse. The exchange elaborates on how Michener began to write fiction, focuses on his great success as a writer, and notes that he and his wife donated over $100 million to educational institutions over the years. Lists five selected works about James Michener and provides a year-by-year Internet search on the author.(BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Assumptions of Law and Justice Party Foreign Policy

Warsaw, May 2016 Change in Poland, but what change? Assumptions of Law and Justice party foreign policy Adam Balcer – WiseEuropa Institute Piotr Buras – European Council on Foreign Relations Grzegorz Gromadzki – Stefan Batory Foundation Eugeniusz Smolar – Centre for International Relations The deep reform of the state announced by Law and Justice party (PiS) and its unquestioned leader, Jarosław Kaczyński, and presented as the “Good Change”, to a great extent also influences foreign, especially European, policy. Though PiS’s political project has been usually analysed in terms of its relation to the post 1989, so called 3rd Republic institutional-political model and the results of the socio-economic transformation of the last 25 years, there is no doubt that in its alternative concept for Poland, the perception of the world, Europe and Poland’s place in it, plays a vital role. The “Good Change” concept implies the most far-reaching reorientation in foreign policy in the last quarter of a century, which, at the level of policy declarations made by representatives of the government circles and their intellectual supporters implies the abandonment of a number of key assumptions that shaped not only policy but also the imagination of the Polish political elite and broad society as a whole after 1989. The generally accepted strategic aim after 1989 was to avoid the “twilight zone” of uncertainty and to anchor Poland permanently in the western security system – i.e. NATO, and European political, legal and economic structures, in other words the European Union. “Europeanisation” was the doctrine of Stefan Batory Foundation Polish transformation after 1989. -

Dear President, Dear Ursula, We Welcome the Letter of 1 March That

March 8, 2021 Dear President, dear Ursula, We welcome the letter of 1 March that you received from Chancellor Merkel and PM Frederiksen, PM Kallas and PM Marin. We share many of the ideas outlined in the letter. Indeed, there are some points that we find are of particular importance as we work to progress the digital agenda for the EU. We certainly agree that our agenda must be founded on a good mix of self-determination and openness. Our approach to digital sovereignty must be geared towards growing digital leadership by preparing for smart and selective action to ensure capacity where called for, while preserving open markets and strengthening global cooperation and the external trade dimension. Digital innovation benefits from partnerships among sectors, promoting public and private cooperation. Translating excellence in research and innovation into commercial successes is crucial to creating global leadership. The Single Market remains key to our prosperity and to the productivity and competitiveness of European companies, and our regulatory framework needs to be made fit for the digital age. We need a Digital Single Market for innovation, to eliminate barriers to cross-border online services, and to ensure free data flows. Attention must be paid to the external dimension where we should continue to work closely with our allies around the world and where in our interest, develop new partnerships. We need to make sure that the EU can be a leader of a responsible digital transformation. Trust and innovation are two sides of the same coin. Europe’s competitiveness should be built on efficient, trustworthy, transparent, safe and responsible use of data in accordance with our shared values. -

Annual Report the PARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY of the MEDITERRANEAN

PARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY OF THE MEDITERRANEAN ASSEMBLEE PARLEMENTAIRE DE LA MEDITERRANEE اﻟﺠﻤﻌﻴﺔ اﻟﺒﺮﻟﻤﺎﻧﻴﺔ ﻟﻠﺒﺤﺮ اﻷﺑﻴﺾ اﻟﻤﺘﻮﺳﻂ a v n a C © 2020 Annual Report THE PARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY OF THE MEDITERRANEAN The Parliamentary Assembly of the Mediterranean (PAM) is an international organization, which brings together 34 member parliaments from the Euro-Mediterranean and Gulf regions to discuss the most pressing common challenges, such as regional conflicts, security and counterterrorism, humanitarian crises, economic integration, climate change, mass migrations, education, human rights and inter-faith dialogue. Through this unique political forum, PAM Parliaments are able to engage in productive discussions, share legislative experience, and work together towards constructive solutions. a v n 2 a C © CONTENTS FOREWORD 4 14TH PLENARY SESSION 6 REPORT OF ACTIVITIES 9 1ST STANDING COMMITTEE - POLITICAL AND SECURITY-RELATED COOPERATION 11 2ND STANDING COMMITTEE - ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL COOPERATION 16 3RD STANDING COMMITTEE - DIALOGUE AMONG CIVILIZATIONS AND HUMAN RIGHTS 21 KEY EVENTS 2020 28 PAM 2020 DOCUMENTS – QUICK ACCESS LINKS 30 PAM AWARDS 2020 33 MANAGEMENT AND FINANCIAL REMARKS 36 FINANCIAL REPORT 39 CALENDAR 2020 49 PRELIMINARY CALENDAR 2021 60 3 a v n a C © FOREWORD Hon. Karim Darwish President of PAM Dear Colleagues and friends, It has been a privilege and an honor to act as the President of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Mediterranean in 2020. As this year draws to a close, I would like to reiterate my deep gratitude to all PAM delegates and their National Parliaments, the PAM Secretariat and our partner organizations for their great work and unwavering support during a time when our region Honorable Karim Darwish, President of PAM and the world face a complex array of challenges. -

Declining Support for Government of Donald Tusk and for Civic Platform (Po)

DECLINING SUPPORT FOR GOVERNMENT OF DONALD TUSK AND FOR CIVIC PLATFORM (PO) The coalition of Civic Platform and Polish Peasant Party (PO-PSL), which has governed Poland for over four years, is losing social support. Evaluations of the government of Donald Tusk have deteriorated. At present, they are the worst, if both parliamentary terms are considered. The decline was precipitated by, among others, problems with implementation of new rules on refunding medicines, signing of the ACTA agreement (a decision from which the government eventually withdrew), and planned changes in the pension system, especially raising the retirement age to 67 years. From Dec. 2011 to March 2012 the proportion of government supporters fell from 44% to 31%, while the number of opponents rose from 31% to 45%. ATTITUDE TO THE GOVERNMENT OF DONALD TUSK “Don't know” omitted The popularity of the Prime Minster is diminishing. The proportion of respondents satisfied with the work of Donald Tusk as Prime Minister fell from 49% in Dec. 2011 to 33% in March 2012. At the same time, the number of the dissatisfied rose from 38% to 57%. SATISFACTION WITH DONALD TUSK AS PRIME MINISTER “Don't know” omitted The effects of government's activities are perceived ever more critically. The proportion of people satisfied with them fell in the last four months from 45% to 25%, while the number of the dissatisfied rose from 40% to 67%. EVALUATION OF EFFECTS OF ACTIVITY OF DONALD TUSK'S GOVERNMENT UP TO DATE “Don't know” omitted The decline in support for the government is accompanied by a drop in the ratings of the Civic Platform (PO). -

LETTER to G20, IMF, WORLD BANK, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS and NATIONAL GOVERNMENTS

LETTER TO G20, IMF, WORLD BANK, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS and NATIONAL GOVERNMENTS We write to call for urgent action to address the global education emergency triggered by Covid-19. With over 1 billion children still out of school because of the lockdown, there is now a real and present danger that the public health crisis will create a COVID generation who lose out on schooling and whose opportunities are permanently damaged. While the more fortunate have had access to alternatives, the world’s poorest children have been locked out of learning, denied internet access, and with the loss of free school meals - once a lifeline for 300 million boys and girls – hunger has grown. An immediate concern, as we bring the lockdown to an end, is the fate of an estimated 30 million children who according to UNESCO may never return to school. For these, the world’s least advantaged children, education is often the only escape from poverty - a route that is in danger of closing. Many of these children are adolescent girls for whom being in school is the best defence against forced marriage and the best hope for a life of expanded opportunity. Many more are young children who risk being forced into exploitative and dangerous labour. And because education is linked to progress in virtually every area of human development – from child survival to maternal health, gender equality, job creation and inclusive economic growth – the education emergency will undermine the prospects for achieving all our 2030 Sustainable Development Goals and potentially set back progress on gender equity by years. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

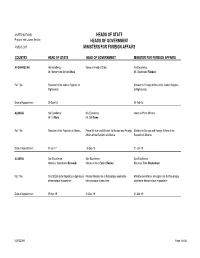

HEADS of STATE Protocol and Liaison Service HEADS of GOVERNMENT PUBLIC LIST MINISTERS for FOREIGN AFFAIRS

UNITED NATIONS HEADS OF STATE Protocol and Liaison Service HEADS OF GOVERNMENT PUBLIC LIST MINISTERS FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS COUNTRY HEAD OF STATE HEAD OF GOVERNMENT MINISTER FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS AFGHANISTAN His Excellency Same as Head of State His Excellency Mr. Mohammad Ashraf Ghani Mr. Salahuddin Rabbani Full Title President of the Islamic Republic of Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Islamic Republic Afghanistan of Afghanistan Date of Appointment 29-Sep-14 02-Feb-15 ALBANIA His Excellency His Excellency same as Prime Minister Mr. Ilir Meta Mr. Edi Rama Full Title President of the Republic of Albania Prime Minister and Minister for Europe and Foreign Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs of the Affairs of the Republic of Albania Republic of Albania Date of Appointment 24-Jul-17 15-Sep-13 21-Jan-19 ALGERIA Son Excellence Son Excellence Son Excellence Monsieur Abdelkader Bensalah Monsieur Nour-Eddine Bedoui Monsieur Sabri Boukadoum Full Title Chef d'État de la République algérienne Premier Ministre de la République algérienne Ministre des Affaires étrangères de la République démocratique et populaire démocratique et populaire algérienne démocratique et populaire Date of Appointment 09-Apr-19 31-Mar-19 31-Mar-19 31/05/2019 Page 1 of 66 COUNTRY HEAD OF STATE HEAD OF GOVERNMENT MINISTER FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS ANDORRA Son Excellence Son Excellence Son Excellence Monseigneur Joan Enric Vives Sicília Monsieur Xavier Espot Zamora Madame Maria Ubach Font et Son Excellence Monsieur Emmanuel Macron Full Title Co-Princes de la Principauté d’Andorre Chef du Gouvernement de la Principauté d’Andorre Ministre des Affaires étrangères de la Principauté d’Andorre Date of Appointment 16-May-12 21-May-19 17-Jul-17 ANGOLA His Excellency His Excellency Mr.