Young People, Precarious Employment and Nationalism in Poland: Exploring the (Missing) Links

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assumptions of Law and Justice Party Foreign Policy

Warsaw, May 2016 Change in Poland, but what change? Assumptions of Law and Justice party foreign policy Adam Balcer – WiseEuropa Institute Piotr Buras – European Council on Foreign Relations Grzegorz Gromadzki – Stefan Batory Foundation Eugeniusz Smolar – Centre for International Relations The deep reform of the state announced by Law and Justice party (PiS) and its unquestioned leader, Jarosław Kaczyński, and presented as the “Good Change”, to a great extent also influences foreign, especially European, policy. Though PiS’s political project has been usually analysed in terms of its relation to the post 1989, so called 3rd Republic institutional-political model and the results of the socio-economic transformation of the last 25 years, there is no doubt that in its alternative concept for Poland, the perception of the world, Europe and Poland’s place in it, plays a vital role. The “Good Change” concept implies the most far-reaching reorientation in foreign policy in the last quarter of a century, which, at the level of policy declarations made by representatives of the government circles and their intellectual supporters implies the abandonment of a number of key assumptions that shaped not only policy but also the imagination of the Polish political elite and broad society as a whole after 1989. The generally accepted strategic aim after 1989 was to avoid the “twilight zone” of uncertainty and to anchor Poland permanently in the western security system – i.e. NATO, and European political, legal and economic structures, in other words the European Union. “Europeanisation” was the doctrine of Stefan Batory Foundation Polish transformation after 1989. -

Uphill Struggle for the Polish Greens

“The Most Challenging Term Since 1989”: Uphill Struggle for the Polish Greens Article by Urszula Zielińska July 9, 2021 Rising corruption, shrinking democratic freedoms, and a crackdown on free media: the political landscape in Poland is challenging to say the least. After a long struggle, Polish Greens made it into parliament in 2019, where they have been standing in solidarity with protestors and fighting to put green issues on the agenda. We asked Green MP Urszula Zielińska how the environment and Europe fit into the Polish political debate, and how Greens are gearing up ahead of local and parliamentary elections in 2023. This interview is part of a series that we are publishing in partnership with Le Grand Continent on green parties in Europe. Green European Journal: 2020 saw presidential elections in Poland as well as a great wave of protest provoked by further restrictions to abortion rights. The pandemic is ongoing in Poland as everywhere. How are the Greens approaching the main issues in Polish politics in 2021? Urszula Zielinska: This period is significant for the Greens. We entered parliament for the first time after the October 2019 election with three MPs as part of a coalition with the Christian Democrat party Civic Platform (PO) and two other partners (The Modern Party and Initiative Poland). It’s taken the Greens 14 years to reach this point and the coalition helped us gain our first MPs. But at the same time, it has been an extremely difficult parliamentary term in general for Poland. In some respects, it may have been the most challenging term in 30 years of free, democratic Poland. -

The October 2015 Polish Parliamentary Election

An anti-establishment backlash that shook up the party system? The october 2015 Polish parliamentary election Article (Accepted Version) Szczerbiak, Aleks (2016) An anti-establishment backlash that shook up the party system? The october 2015 Polish parliamentary election. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 18 (4). pp. 404-427. ISSN 1570-5854 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/63809/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk An anti-establishment backlash that shook up the party system? The October 2015 Polish parliamentary election Abstract The October 2015 Polish parliamentary election saw the stunning victory of the right-wing opposition Law and Justice party which became the first in post-communist Poland to secure an outright parliamentary majority, and equally comprehensive defeat of the incumbent centrist Civic Platform. -

EUROPEAN ELECTIONS in the V4 from Disinformation Campaigns to Narrative Amplification

Strategic Communication Programme EUROPEAN ELECTIONS IN THE V4 From disinformation campaigns to narrative amplification 1 AUTHORS Miroslava Sawiris, Research Fellow, StratCom Programme, GLOBSEC, Slovakia Lenka Dušková, Project Assistant, PSSI, Czech Republic Jonáš Syrovátka, Programme Manager, PSSI, Czech Republic Lóránt Győri, Geopolitical Analyst, Political Capital, Hungary Antoni Wierzejski, Member of the Board, Euro-Atlantic Association, Poland GLOBSEC and National Endowment for Democracy assume no responsibility for the facts or opinions expressed in this publication or their subsequent use. The sole responsibility lies with the authors of this report. METHODOLOGY Data were collected between 10.4.2019 and 29.5.2019 from 15 relevant Facebook pages in each V4 country based on the following criteria: local experts and publicly available sources (such as blbec.online) identified Facebook channels that often publish disinformation content. In the selection of Facebook pages, those openly affiliated with a specific political party were omitted, including the Facebook pages of individual candidates. The data were filtered using different forms of the term “election” in local languages and the term “euro”, and then labelled based on the sentiment toward relevant political parties and the most prevalent narratives identified. © GLOBSEC GLOBSEC, Bratislava, Slovakia June 2019 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Czechia 4 Hungary 4 Poland 4 Slovakia 4 ACTIVITY OF THE MONITORED CHANNELS ACROSS THE V4 REGION 6 Intensity of the campaigns 6 -

Poland and Its Relations with the United States

Poland and Its Relations with the United States Derek E. Mix Analyst in European Affairs March 7, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44212 Poland and Its Relations with the United States Summary Over the past 25 years, the relationship between the United States and Poland has been close and cooperative. The United States strongly supported Poland’s accession to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1999 and backed its entry into the European Union (EU) in 2004. In recent years, Poland has made significant contributions to U.S.- and NATO-led military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, and Poland and the United States continue working together on issues such as democracy promotion, counterterrorism, and improving NATO capabilities. Given its role as a close U.S. ally and partner, developments in Poland and its relations with the United States are of continuing interest to the U.S. Congress. This report provides an overview and assessment of some of the main dimensions of these topics. Domestic Political and Economic Issues The Polish parliamentary election held on October 25, 2015, resulted in a victory for the conservative Law and Justice Party. Law and Justice won an absolute majority of seats in the lower house of parliament (Sejm), and Beata Szydlo took over as the country’s new prime minister in November 2015. The center-right Civic Platform party had previously led the government of Poland since 2007. During its first months in office, Law and Justice has made changes to the country’s Constitutional Tribunal and media law that have generated concerns about backsliding on democracy and triggered an EU rule-of-law investigation. -

Law and Justice's Stunning Victory in Poland Reflected Widespread

blogs.lse.ac.uk http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2015/11/02/law-and-justices-stunning-victory-in-poland-reflected-widespread-disillusionment-with-the- countrys-ruling-elite/ Law and Justice’s stunning victory in Poland reflected widespread disillusionment with the country’s ruling elite What does the recent parliamentary election in Poland tell us about the country’s politics? Aleks Szczerbiak writes that the victory secured by the right-wing opposition party Law and Justice stemmed from widespread disillusionment with Poland’s ruling elite. He notes that the usual strategy employed by the ruling party, Civic Platform, of trying to mobilise the ‘politics of fear’ against Law and Justice was not successful this time. The election result heralds major changes on the political scene including a leadership challenge in Civic Platform, the emergence of new ‘anti-system’ and liberal political forces in parliament, and a period of soul searching for the marginalised Polish left. Poland’s October 25th parliamentary election saw a stunning victory for the right-wing Law and Justice (PiS) party, previously the main opposition grouping. The party increased its share of the vote by 7.7 per cent – compared with the previous 2011 poll – to 37.6 per cent, securing 235 seats in the 460-member Sejm, the more powerful lower house of the Polish parliament. This made Law and Justice the first political grouping in post-communist Poland to secure an outright parliamentary majority. At the same time, the centrist Civic Platform (PO), the outgoing ruling party led by prime minister Ewa Kopacz, suffered a crushing defeat, seeing its vote share fall by 15.1 per cent to only 24.1 per cent and number of seats drop to 138. -

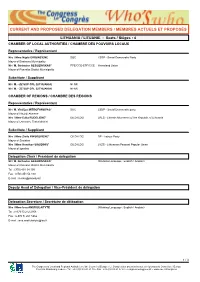

Current and Proposed Delegation Members

&855(17$1'352326(''(/(*$7,210(0%(560(0%5(6$&78(/6(7352326e6 /,7+8$1,$/,78$1,(6HDWV6LqJHV CHAMBER OF LOCAL AUTHORITIES / CHAMBRE DES POUVOIRS LOCAUX 5HSUHVHQWDWLYH5HSUpVHQWDQW 0UV0PH1LMROp',5*,1&,(1( SOC LSDP - Social Democratic Party Mayor of Birstonas Municipality Mr / M. Gintautas GEGUZINSKAS* PPE/CCE-EPP/CCE Homeland Union Mayor of Pasvalys District Municipality 6XEVWLWXWH6XSSOpDQW Mr / M. - ZZ SUP CPL (LITHUANIA) NI-NR Mr / M. - ZZ SUP CPL (LITHUANIA) NI-NR &+$0%(52)5(*,216&+$0%5('(65e*,216 5HSUHVHQWDWLYH5HSUpVHQWDQW Mr / M. Vitalijus MITROFANOVAS* SOC LSDP - Social Democratic party Mayor of Naujoji Akmene Mrs / Mme Edita RUDELIENE* GILD-ILDG LRLS - Liberals Movement of the Republic of Lithuania Mayor of Lentvaris, Trakai district 6XEVWLWXWH6XSSOpDQW Mrs / Mme Zivile PINSKUVIENE* GILD-ILDG DP - Labour Party Mayor of Sirvintos Mrs / Mme Henrikas SIAUDINIS* GILD-ILDG LVZS - Lithuanian Peasant Popular Union Mayor of Ignalina 'HOHJDWLRQ&KDLU3UpVLGHQWGHGpOpJDWLRQ Mr / M. Gintautas GEGUZINSKAS* (Working Language : English / Anglais) Mayor of Pasvalys District Municipality Tel : (370) 451 54 100 Fax : (370) 451 54 130 E-mail : [email protected] 'HSXW\+HDGRI'HOHJDWLRQ9LFH3UpVLGHQWGHGpOpJDWLRQ 'HOHJDWLRQ6HFUHWDU\6HFUpWDLUHGHGpOpJDWLRQ Mrs / Mme Ieva ANDRIULAITYTE (Working Language : English / Anglais) Tel : (+370 5) 212 2958 Fax : (+370 5) 261 5366 E-mail : [email protected] 1 / 3 7KH&RQJUHVVRI/RFDODQG5HJLRQDO$XWKRULWLHVRIWKH&RXQFLORI(XURSH/H&RQJUqVGHVSRXYRLUVORFDX[HWUpJLRQDX[GX&RQVHLOGHO¶Europe F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex ±7pO33 (0)3 88 41 21 10±Fax : +33 (0)3 88 41 37 47±[email protected] ±www.coe.int/congress 32/$1'32/2*1(6HDWV6LqJHV CHAMBER OF LOCAL AUTHORITIES / CHAMBRE DES POUVOIRS LOCAUX 5HSUHVHQWDWLYH5HSUpVHQWDQW Mr / M. Robert BIEDRON SOC Independant Mayor Slupsk Mr / M. -

The Polish Paradox: from a Fight for Democracy to the Political Radicalization and Social Exclusion

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article The Polish Paradox: From a Fight for Democracy to the Political Radicalization and Social Exclusion Zofia Kinowska-Mazaraki Department of Studies of Elites and Political Institutions, Institute of Political Studies of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Polna 18/20, 00-625 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] Abstract: Poland has gone through a series of remarkable political transformations over the last 30 years. It has changed from a communist state in the Soviet sphere of influence to an autonomic prosperous democracy and proud member of the EU. Paradoxically, since 2015, Poland seems to be heading rapidly in the opposite direction. It was the Polish Solidarity movement that started the peaceful revolution that subsequently triggered important democratic changes on a worldwide scale, including the demolition of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of Communism and the end of Cold War. Fighting for freedom and independence is an important part of Polish national identity, sealed with the blood of generations dying in numerous uprisings. However, participation in the democratic process is curiously limited in Poland. The right-wing, populist Law and Justice Party (PiS) won elections in Poland in 2015. Since then, Poles have given up more and more freedoms in exchange for promises of protection from different imaginary enemies, including Muslim refugees and the gay and lesbian community. More and more social groups are being marginalized and deprived of their civil rights. The COVID-19 pandemic has given the ruling party a reason to further limit the right of assembly and protest. Polish society is sinking into deeper and deeper divisions. -

On the Connection Between Law and Justice Anthony D'amato Northwestern University School of Law, [email protected]

Northwestern University School of Law Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Working Papers 2011 On the Connection Between Law and Justice Anthony D'Amato Northwestern University School of Law, [email protected] Repository Citation D'Amato, Anthony, "On the Connection Between Law and Justice" (2011). Faculty Working Papers. Paper 2. http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/facultyworkingpapers/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. On the Connection Between Law and Justice, by Anthony D'Amato,* 26 U. C. Davis L. Rev. 527-582 (1992-93) Abstract: What does it mean to assert that judges should decide cases according to justice and not according to the law? Is there something incoherent in the question itself? That question will serve as our springboard in examining what is—or should be—the connection between justice and law. Legal and political theorists since the time of Plato have wrestled with the problem of whether justice is part of law or is simply a moral judgment about law. Nearly every writer on the subject has either concluded that justice is only a judgment about law or has offered no reason to support a conclusion that justice is somehow part of law. This Essay attempts to reason toward such a conclusion, arguing that justice is an inherent component of the law and not separate or distinct from it. -

The Development of Online Political Communication in Poland in European Parliamentary Elections 2014: Technological Innovation V

ORIGINAL ARTICLE The development of online political communication in Poland in European Parliamentary elections 2014: Technological innovation versus old habits Michał Jacuński UNIVERSITY OF WROCŁAW, POLAND Michał Jacuński, Paweł Baranowski UNIVERSITY OF WROCŁAW, POLAND ABSTRACT: Th is article analyzes the methods of electoral communication during the 2014 European Parliament election in Poland. Are Polish candidates to the European Parliament stuck with the old habits and patterns of communication or have they adopted all the available technological innova- tions? Constant technological evolution and increasing Internet usage-rate are not only giving the candidates new possibilities to reach potential voters, but they also pose a challenge. By using content analysis, we have analyzed the structure of candidates’ websites and their offi cial Facebook and Twit- ter profi les. We also analyzed the level of interactivity with candidates’ fans on Facebook and open- ness to two-way communication on websites, a “must” in the late web 2.0 era. KEYWORDS: European Parliament, elections, online political communication, owned media, so- cial media, web campaigning, participation INTRODUCTION According to communication research theoreticians, nowadays “one cannot not communicate” (Motley, 1990). Th rough communication one can fully participate in social groups and processes. When it comes to cyberspace, the above men- tioned rule, originating from communication theoreticians of the Palo Alto school of the 1960s and 1970s, is particularly evident and relates mainly to two- way communication processes in social media. Social media are the media (Dew- ing, 2012) which we use to become socialized (Safk o, 2010), using one of the basic attributes of the human species — communication with other members of the group. -

The 2000 Presidential Election in Poland

THE 2000 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION IN POLAND Krzysztof Jasiewic z Washington and Lee University The National Council for Eurasian and East European Researc h 910 17 th Street, N.W . Suite 300 Washington, D .C. 20006 TITLE VIII PROGRAM Project Information* Principal Investigator : Krzysztof Jasiewicz Council Contract Number : 8L5-08g Date : July 9, 200 1 Copyright Informatio n Scholars retain the copyright on works they submit to NCEEER . However, NCEEER possesse s the right to duplicate and disseminate such products, in written and electronic form, as follows : (a) for its internal use; (b) to the U .S. Government for its internal use or for dissemination to officials o f foreign governments; and (c) for dissemination in accordance with the Freedom of Information Ac t or other law or policy of the U .S. government that grants the public access to documents held by th e U.S. government. Additionally, NCEEER has a royalty-free license to distribute and disseminate papers submitted under the terms of its agreements to the general public, in furtherance of academic research , scholarship, and the advancement of general knowledge, on a non-profit basis. All paper s distributed or disseminated shall bear notice of copyright. Neither NCEEER, nor the U .S . Government, nor any recipient of a Contract product may use it for commercial sale . ' The work leading to this report was supported in part by contract or grant funds provided by the National Council fo r Eurasian and East European Research, funds which were made available by the U .S . Department of State under Title VIII (The Soviet-East European Research and Training Act of 1983, as amended) . -

Poland's Rock Star-Politician: What Happened to Paweł Kukiz?

Poland’s rock star-politician: What happened to Paweł Kukiz? blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2016/05/11/polands-rock-star-politician-what-happened-to-pawel-kukiz/ 5/11/2016 A year ago rock star and social activist Paweł Kukiz caused a sensation when he finished a surprise third in the first round of the Polish presidential election. He held on to enough support for his new Kukiz ‘15 grouping to secure representation in the legislature after the October parliamentary election. Aleks Szczerbiak writes that Kukiz ‘15 has retained a reasonably stable base of support, but its lack of organisational and programmatic coherence casts doubt over the grouping’s long-term prospects, which are closely linked to its leader’s personal credibility. Election success in spite of blunders Last May the charismatic rock star and social activist Paweł Kukiz caused a political sensation when he came from nowhere to finish third in the first round of the Polish presidential election, picking up more than one fifth of the vote. Standing as an independent right-wing ‘anti-system’ candidate, Mr Kukiz’s signature issue, and main focus of his earlier social activism, was strong support for the replacement of Poland’s current list-based proportional electoral system with UK-style single-member constituencies (known by the Polish acronym ‘JOW’), which he saw as the key to renewing Polish politics. Opinion polls conducted immediately after the presidential poll showed Mr Kukiz to be Poland’s most trusted politician and his (as-yet-unnamed) grouping running in second place behind the right- wing Law and Justice (PiS) party – the main opposition grouping, which went on to win a decisive victory in the parliamentary election – but ahead of the ruling centrist Civic Platform (PO).