CONTINGENCY in POSTSITUATIONIST ARCHITECTURE Phd Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Support to Commercial Space Launch

The Space Congress® Proceedings 2019 (46th) Light the Fire Jun 4th, 3:30 PM Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Support to Commercial Space Launch Thomas Ste. Marie Vice Commander, 45th Space Wing Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/space-congress-proceedings Scholarly Commons Citation Ste. Marie, Thomas, "Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Support to Commercial Space Launch" (2019). The Space Congress® Proceedings. 31. https://commons.erau.edu/space-congress-proceedings/proceedings-2019-46th/presentations/31 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Space Congress® Proceedings by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Support to Commercial Space Launch Colonel Thomas Ste. Marie Vice Commander, 45th Space Wing CCAFS Launch Customers: 2013 Complex 41: ULA Atlas V (CST-100) Complex 40: SpaceX Falcon 9 Complex 37: ULA Delta IV; Delta IV Heavy Complex 46: Space Florida, Navy* Skid Strip: NGIS Pegasus Atlantic Ocean: Navy Trident II* Black text – current programs; Blue text – in work; * – sub-orbital CCAFS Launch Customers: 2013 Complex 39B: NASA SLS Complex 41: ULA Atlas V (CST-100) Complex 40: SpaceX Falcon 9 Complex 37: ULA Delta IV; Delta IV Heavy NASA Space Launch System Launch Complex 39B February 4, 2013 Complex 46: Space Florida, Navy* Skid Strip: NGIS Pegasus Atlantic Ocean: Navy Trident II* Black text – current programs; -

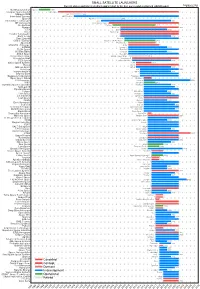

Small Satellite Launchers

SMALL SATELLITE LAUNCHERS NewSpace Index 2020/04/20 Current status and time from development start to the first successful or planned orbital launch NEWSPACE.IM Northrop Grumman Pegasus 1990 Scorpius Space Launch Demi-Sprite ? Makeyev OKB Shtil 1998 Interorbital Systems NEPTUNE N1 ? SpaceX Falcon 1e 2008 Interstellar Technologies Zero 2021 MT Aerospace MTA, WARR, Daneo ? Rocket Lab Electron 2017 Nammo North Star 2020 CTA VLM 2020 Acrux Montenegro ? Frontier Astronautics ? ? Earth to Sky ? 2021 Zero 2 Infinity Bloostar ? CASIC / ExPace Kuaizhou-1A (Fei Tian 1) 2017 SpaceLS Prometheus-1 ? MISHAAL Aerospace M-OV ? CONAE Tronador II 2020 TLON Space Aventura I ? Rocketcrafters Intrepid-1 2020 ARCA Space Haas 2CA ? Aerojet Rocketdyne SPARK / Super Strypi 2015 Generation Orbit GoLauncher 2 ? PLD Space Miura 5 (Arion 2) 2021 Swiss Space Systems SOAR 2018 Heliaq ALV-2 ? Gilmour Space Eris-S 2021 Roketsan UFS 2023 Independence-X DNLV 2021 Beyond Earth ? ? Bagaveev Corporation Bagaveev ? Open Space Orbital Neutrino I ? LIA Aerospace Procyon 2026 JAXA SS-520-4 2017 Swedish Space Corporation Rainbow 2021 SpinLaunch ? 2022 Pipeline2Space ? ? Perigee Blue Whale 2020 Link Space New Line 1 2021 Lin Industrial Taymyr-1A ? Leaf Space Primo ? Firefly 2020 Exos Aerospace Jaguar ? Cubecab Cab-3A 2022 Celestia Aerospace Space Arrow CM ? bluShift Aerospace Red Dwarf 2022 Black Arrow Black Arrow 2 ? Tranquility Aerospace Devon Two ? Masterra Space MINSAT-2000 2021 LEO Launcher & Logistics ? ? ISRO SSLV (PSLV Light) 2020 Wagner Industries Konshu ? VSAT ? ? VALT -

Space Coast Is Getting Busy: 6 New Rockets Coming to Cape Canaveral, KSC

4/16/2019 Space Coast is getting busy: 6 new rockets coming to Cape Canaveral, KSC Space Coast is getting busy: 6 new rockets coming to Cape Canaveral, Kennedy Space Center Emre Kelly, Florida Today Published 4:04 p.m. ET April 11, 2019 | Updated 7:53 a.m. ET April 12, 2019 COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. – If schedules hold, the Space Coast will live up to its name over the next two years as a half-dozen new rockets target launches from sites peppered across the Eastern Range. Company, government and military officials here at the 35th Space Symposium, an annual space conference, have reaffirmed their plans to launch rockets ranging from more traditional heavy-lift behemoths to smaller vehicles that take advantage of new manufacturing technologies. Even if some of these schedules slip, at least one thing is apparent to several spaceflight experts here: The Eastern Range is seeing an unprecedented growth in commercial space companies and efforts. Space Launch System: 2020 NASA's Space Launch System rocket launches from Kennedy Space Center's pad 39B in this rendering by the agency. (Photo: NASA) NASA's long-awaited SLS, a multibillion-dollar rocket announced in 2011, is slated to become the most powerful launch vehicle in history if it can meet a stringent late 2020 deadline. The 322-foot-tall rocket is expected to launch on its first flight – Exploration Mission 1 – from Kennedy Space Center with an uncrewed Orion capsule for a mission around the moon, which fits in with the agency's wider goal of putting humans on the surface by 2024. -

Espinsights the Global Space Activity Monitor

ESPInsights The Global Space Activity Monitor Issue 6 April-June 2020 CONTENTS FOCUS ..................................................................................................................... 6 The Crew Dragon mission to the ISS and the Commercial Crew Program ..................................... 6 SPACE POLICY AND PROGRAMMES .................................................................................... 7 EUROPE ................................................................................................................. 7 COVID-19 and the European space sector ....................................................................... 7 Space technologies for European defence ...................................................................... 7 ESA Earth Observation Missions ................................................................................... 8 Thales Alenia Space among HLS competitors ................................................................... 8 Advancements for the European Service Module ............................................................... 9 Airbus for the Martian Sample Fetch Rover ..................................................................... 9 New appointments in ESA, GSA and Eurospace ................................................................ 10 Italy introduces Platino, regions launch Mirror Copernicus .................................................. 10 DLR new research observatory .................................................................................. -

The Right Rocket for the Job: Small Launch Providers Target Small Satellites

The Right Rocket for the Job: Small Launch Providers Target Small Satellites An STS Research Paper presented to the faculty of the School of Engineering and Applied Science University of Virginia by Gabriel Norris May 11, 2020 On my honor as a University student, I have neither given nor received unauthorized aid on this assignment as defined by the Honor Guidelines for Thesis-Related Assignments. Signed: _________________________________________________ Approved: _______________________________________ Date ________________________ Peter Norton, Department of Engineering and Society 2 The University of Virginia Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering has its first satellite, Libertas, now in orbit and plans to launch two more within the next three years. This sudden activity is representative of the vastly increased smallsat1 launch cadence by a variety of groups around the world. The trend is facilitated by the reduced cost and relative ease of assembly conferred by CubeSats, which collectively make up 70 percent of satellites launched today (Halt & Wieger, 2019). Startups, underdeveloped countries, and universities that, just ten years ago, would have been incapable of any kind of space mission are now launching several. From 2012 to 2019, 663 CubeSats were manufactured by private companies, nearly 300 by governments or militaries, and 371 by academic institutions. Yearly satellite launches have increased six-fold in this time (Halt & Wieger, 2019; fig. 1). This marked increase in customers underscores a sociotechnical problem in the rocketry industry: most rockets are fairly large and cater primarily to large satellites, leaving behind a large number of customers in the smallsat domain. Satellites broadly fall within four categories of use: remote sensing, communication, technology demonstration, and scientific investigation. -

Undergraduate Thesis Prospectus Design And

Undergraduate Thesis Prospectus Design and Construction of an Amateur Radio CubeSat (technical research project in Aerospace Engineering) The Right Rocket for the Job: Small Launch Providers Target Small Satellites (STS research project) by Gabriel Norris October 31, 2019 technical project collaborators: MAE 4690/4700 Spacecraft Design Team On my honor as a University student, I have neither given nor received unauthorized aid on this assignment as defined by the Honor Guidelines for Thesis-Related Assignments. signed: __________________________________________ date: ________________ approved: ________________________________________ date: ________________ Peter Norton, Department of Engineering and Society approved: ________________________________________ date: ________________ Christopher Goyne, Department of Aerospace Engineering 2 General Research Problem: Small Satellites in Low Earth Orbit How can we efficiently and reliably put scientific and communications equipment into orbit? The development of radio telecommunications transformed human communication. The line-of-sight propagation of most radio signals, however, kept the technology from enabling truly global communication for some time. By 1927, it was possible to bounce high-energy radio waves off the ionosphere, which enabled transcontinental radiotelephony, but at a very high cost and with poor signal quality. In October 1945, Arthur C. Clarke published an article proposing the concept of a satellite constellation for the purpose of relaying signals around the world, a full twelve years before the launch of Sputnik 1 (Clarke, 1945). In 1958, Clarke’s vision came to pass with the launch of the first communications satellite SCORE, which broadcast a Christmas greeting from President Eisenhower to the entire world (Martin, 2007). Now over 2,000 satellites orbit the Earth and the world is more interconnected than ever. -

Systems-Theoretic Process Analysis of Space Launch Vehicles ⁎ John M

The Journal of Space Safety Engineering xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect The Journal of Space Safety Engineering journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jsse Systems-Theoretic Process Analysis of space launch vehicles ⁎ John M. Risinga, , Nancy G. Levesonb a Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA b Aeronautics and Astronautics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA ABSTRACT This article demonstrates how Systems-Theoretic Process Analysis (STPA) can be used as a powerful tool to identify, mitigate, and eliminate hazards throughout the space launch system lifecycle. Hazard analysis tech- niques commonly used to evaluate launch vehicle safety use reliability theory as their foundation, but most modern space launch vehicle accidents have resulted from design errors or other factors independent of com- ponent reliability. This article reviews safety analysis methods as they are applied to space launch vehicles, and demonstrates that they are unable to treat many of the causal factors associated with modern launch accidents. Next, it describes how STPA can be applied to the design of space launch vehicles to treat these casual factors. Safety-guided design with STPA is then demonstrated with a hypothetical small-lift launch vehicle, launch safety system, and upper stage propulsion system. 1. Introduction reliability-based tools often used to evaluate safety are unable to predict or analyze software and component interactions. Furthermore, the 1.1. Motivation growing popularity of autonomous flight termination systems (AFTS) reinforces the need for software safety analysis tools. Designers of The causal factors of launch vehicle accidents are changing. Early launch systems need hazard analysis tools that are better equipped to accidents were often caused by electromechanical component failures, handle these new causes of launch vehicle accidents. -

Start-Up Space Report 2020

Start-Up Space Update on Investment in Commercial Space Ventures 2020 i Bryce Space and Technology brycetech.com CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................... III INTRODUCTION. 1 Purpose and Background . 1 Methodology ...................................................1 OVERVIEW OF START-UP SPACE VENTURES. 3 TYPES OF SPACE INVESTOR ......................................4 SPACE INVESTMENT BY THE NUMBERS ...........................11 Seed Funding . 15 Venture Capital . 16 Private Equity . 17 Acquisition ...................................................18 Public Offering ................................................19 Debt Financing . 19 Investment Across All Types .....................................19 Valuation ....................................................21 Casualties ...................................................22 SPACE INVESTORS BY THE NUMBERS ............................23 Overall ......................................................23 Angels ......................................................27 Venture Capital Firms . 28 Private Equity Groups ..........................................31 Corporations . 32 Banks and Other Financial Institutions .............................33 SPECIAL TOPIC: CHINESE ACTIVITY IN START-UP SPACE VENTURES. 35 START-UP SPACE: WHAT’S NEXT?. 38 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. 41 ii brycetech.com Bryce Space and Technology EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Three significant trends are shaping the start-up space environment as we enter the 2020s. First, investors continue to pour large amounts -

Tough Crowd: Small Launch Vehicles Seek Niche in Ultra-Competitive Market

Tough crowd: Small launch vehicles seek niche in ultra-competitive market Date Posted: 13-Aug-2020 Author: Pat Host, Washington, DC Publication: Jane's International Defence Review More companies than ever are developing small launch vehicles, but must address market economics and an industry behemoth that could undercut them. Pat Host reports The small launch vehicle market, roughly defined as rockets carrying payloads of 250 kg or less, is as competitive as ever. About 100 companies are developing small rockets, and many started years ago to fulfill an expected demand for hundreds of launches per day of disaggregated low Earth orbit (LEO) satellites. This market failed to develop. Janes analysis suggests the small launch market can support two to three, maybe four companies. In addition, industry behemoth Space Exploration Technologies Corp (SpaceX), is now offering rideshare opportunities on its Falcon 9 rocket at USD5,000 per kg. An industry executive, who was given anonymity to discuss market pricing, told Janes in May that this may be 10-times cheaper than custom launches being offered by existing small launch providers. The executive said the challenge facing small rocket developers is that large vehicles, such as SpaceX’s Falcon 9, can launch 50-times as many satellites as a small vehicle, while costing only five times as much to make the rocket. Planet, a satellite imagery provider, signed contracts for multiple launches of three 115 kg spacecraft at a time on Falcon 9 as a ride share. © 2020 Jane’s Group UK Limited. No portion of this report may be reproduced, reused, or otherwise distributed in any form Page 1 of 16 without prior written consent, with the exception of any internal client distribution as may be permitted in the license agreement between client and Jane’s. -

Espinsights the Global Space Activity Monitor

ESPInsights The Global Space Activity Monitor Issue 5 January-March 2020 CONTENTS FOCUS ..................................................................................................................... 1 The COVID-19 pandemic crisis: the point of view of space ...................................................... 1 SPACE POLICY AND PROGRAMMES .................................................................................... 3 EUROPE ................................................................................................................. 3 Lift-off for ESA Sun-exploring spacecraft ....................................................................... 3 ESA priorities for 2020 ............................................................................................. 3 ExoMars 2022 ........................................................................................................ 3 Airbus’ Bartolomeo Platform headed toward the ISS .......................................................... 3 A European Coordination Committee for the Lunar Gateway ................................................ 4 ESA awards contract to drill and analyse lunar subsoil ........................................................ 4 EU Commission invests in space .................................................................................. 4 Galileo’s Return Link Service is operational .................................................................... 4 Quality control contract on Earth Observation data .......................................................... -

Space Portal Edgar Zapata.Pdf

• • ABOUT ME PUBLICATIONS MORE • NASA NIAC EXTERNAL COUNCIL • [email protected] • ZAPATATALKSNASA.COM 2 • ONLY PART OF THE TOTAL COST TO NASA, DOD, GOVERNMENT (CLOSER TO “PRICE”) • OTHER PUBLIC DATA FOR PERSONNEL/GOVERNMENT AND OTHER PROGRAM/PROJECT RELATED PROCUREMENT COSTS WITH PRIOR, GETS NEAR TO “TOTAL COST” • THE BENEFIT ACROSS TIME, THE CUMULATIVE BENEFIT PRODUCED FOR THAT PRICE/COST, LONG TERM 4 • • • • • • • 5 • • • • • • • • • • • 6 Zapata 4/6/2021 The NASA Budget Education & IG, then Cross Agency Support '07 fwd NASA budget increases = ~ 1.8 % per year average 1995-2020 $24,000 Aerospace incl. R&D to '02 / Aeronautics '03 fwd Science $22,000 Space Flight Support (incl. Payload/Util., LSP, Comm., & SMA) $20,000 Cx '05 Fwd, SLS + Orion + Grd.Sys. '11 Fwd $18,000 NASA BUDGET Expl. R&D: Gateway $16,000 Purchase Power Expl. R&D: Advanced Cis-lunar/Landers, HRT, & Commercial LEO 19% Drop 1995-2021 Purchase Power $14,000 R&D (Many) & LifeSci; now Expl. R&D: AES Science Drop 1995 to 2021 = Space Tech. & Aero-Tech. Space Technology '10 Fwd $12,000 19% ISS R&D $10,000 ISS (Construction to '11, then Ops & Maint.) $8,000 Shift to (Cx/Ares I Cross-cutting Research Constellation canceled) Orion, SLS US Commercial Crew for ISS & Program Budget Begins & Ground Sys. Development $6,000 Management + LifeSci ISS Crew (Soyuz) & Cargo (US Commercial) << ISS 1st ISS Element $4,000 Development Launched Space Shuttle Production, Operations & Upgrades Begins 1985 (Russian) 1998 & Construction >> <-- Shuttle Shuttle Production, Earmarks $2,000 $Millions NASA Budget (Nominal Dollars) (Nominal Budget NASA $Millions Development Begins Operations 1972 & Upgrades Rescissions (2012a) $- 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 Rescissions (2012b) Return To Flight Last Shuttle Columbia Purchase Power (PP) in 1995 $ Decision: End Shuttle post-ISS Flight 2011 Dragon/Cargo Cygnus/Cargo Dragon/Crew & Falcon 9 & Antares to ISS May 8 May 2012 Sept. -

Space News Greg Stanley July 10, 2021 Robotic Missions to Venus Announced

Space News Greg Stanley July 10, 2021 Robotic missions to Venus announced • 2 NASA missions to launch around 2029 • First US missions there in 30 years except flybys • DAVINCI+ (atmospheric analysis, images) • Atmosphere 90x • Parachute a probe (3 foot titanium sphere) in 1 hour thicker than Earth’s descent to surface, 1.5 hour life • Determine how atmosphere evolved, if it had an • 900 °F at surface ocean, look for controversial phosphine life indicator • Sulfuric acid • VERITAS • Radar will update topographic maps • Looking for geologic activity like volcanos, land movement Contrast-enhanced false color image. Credit: NASA/JPL • ESA (European Space Agency) announced similar EnVision mission (2031) • Rocket Lab still plans private mission using Photon craft (2023) • Will orbit, drop a probe, look for that phosphine biomarker • Rocket Lab has NASA contracts to orbit the Moon (2021), Mars (2024) • Why now: climate change emphasis, mostly-discredited recent evidence of life Suborbital space tourism/private astronaut race • Virgin Galactic launch expected July 11 • First launch with passengers (+ 2 pilots) • Richard Branson + 3 other employee passengers • 2 hour ride, mostly in the carrier aircraft, 4- 5 minutes of weightlessness • Blue Origin launch expected on July 20 • First New Shepard launch with people • Jeff Bezos going, taking his brother, 82-year old woman Wally Funk (trained as an Picture credit: Virgin Galactic astronaut), and someone who paid $28M in a charity auction • 10 minute automated ride (no pilots), 3 minutes of weightlessness