Tough Crowd: Small Launch Vehicles Seek Niche in Ultra-Competitive Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Support to Commercial Space Launch

The Space Congress® Proceedings 2019 (46th) Light the Fire Jun 4th, 3:30 PM Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Support to Commercial Space Launch Thomas Ste. Marie Vice Commander, 45th Space Wing Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/space-congress-proceedings Scholarly Commons Citation Ste. Marie, Thomas, "Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Support to Commercial Space Launch" (2019). The Space Congress® Proceedings. 31. https://commons.erau.edu/space-congress-proceedings/proceedings-2019-46th/presentations/31 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Space Congress® Proceedings by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Support to Commercial Space Launch Colonel Thomas Ste. Marie Vice Commander, 45th Space Wing CCAFS Launch Customers: 2013 Complex 41: ULA Atlas V (CST-100) Complex 40: SpaceX Falcon 9 Complex 37: ULA Delta IV; Delta IV Heavy Complex 46: Space Florida, Navy* Skid Strip: NGIS Pegasus Atlantic Ocean: Navy Trident II* Black text – current programs; Blue text – in work; * – sub-orbital CCAFS Launch Customers: 2013 Complex 39B: NASA SLS Complex 41: ULA Atlas V (CST-100) Complex 40: SpaceX Falcon 9 Complex 37: ULA Delta IV; Delta IV Heavy NASA Space Launch System Launch Complex 39B February 4, 2013 Complex 46: Space Florida, Navy* Skid Strip: NGIS Pegasus Atlantic Ocean: Navy Trident II* Black text – current programs; -

2008 Estes-Cox Corp. All Rights Reserved

Estes-Cox Corp. 1295 H Street, P.O. BOX 227 Patent Pending Penrose, CO 81240-0227 ©2008 Estes-Cox Corp. All rights reserved. (9-08) PN 2927-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS HOW DO I START MY OWN ESTES ROCKET FLEET? The best way to begin model rocketry is with an Estes flying model rocket Starter Set or Launch Set. You can ® Index . .2 Skill Level 2 Rocket Kits . .30 either start with a Ready To Fly Starter Set or Launch Set that has a fully constructed model rocket or an E2X How To Start . .3 Skill Level 3 Rocket Kits . .34 Starter Set or Launch Set with a rocket that requires assembly prior to launching. Both types of sets come What to Know . .4 ‘E’ Engine Powered Kits . .36 complete with an electrical launch controller, adjustable launch pad and an information booklet to get you out Model Rocket Safety Code . .5 Blurzz™ Rocket Racers . .36 and flying in no time. Starter Sets include engines, Launch Sets let you choose your own engines (not includ- Ready To Fly Starter Sets . .6 How Model Rocket Engines Work . .38 ed). You’ll need four ‘AA’ alkaline batteries and perhaps glue, depending on which set you select. E2X® Starter Sets . .8 Model Rocket Engine Chart . .39 Ready to Fly Launch Sets . .10 Engine Time/Thrust Curves . .40 Launch Sets . .12 Model Rocket Accessories . .41 HOW EASY AND HOW MUCH TIME DOES IT TAKE TO BUILD MY ROCKETS? Ready To Fly Rockets . .14 Estes R/C Airplanes . .42 ® E2X Rocket Kits . .16 Estes Educator™ Products . -

Astra Space, Inc. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): August 27, 2021 Astra Space, Inc. (Exact name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter) Delaware 001-39426 14-1916687 (State or Other Jurisdiction (Commission File Number) (IRS Employer of Incorporation) Identification No.) 1900 Skyhawk Street Alameda, California 94501 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s Telephone Number, Including Area Code: (866) 278-7217 Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: ☐ Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) ☐ Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Trading Title of each class Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered Class A common stock, par value $0.0001 per share ASTR NASDAQ Global Select Market Warrants to purchase one share of common stock, each at ASTRW NASDAQ Global Select Market an exercise price of $11.50 Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is an emerging growth company as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933 (§ 230.405 of this chapter) or Rule 12b-2 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (§ 240.12b-2 of this chapter). -

GB-ASTRA 3B-Comsatbw-21Mai V

A BOOST FOR SPACE COMMUNICATIONS SATELLITES For its first launch of the year, Arianespace will orbit two communications satellites: ASTRA 3B for the Luxembourg-based operator SES ASTRA, and COMSATBw-2 for Astrium as part of a contract with the German Ministry of Defense. The choice of Arianespace by leading space communications operators and manufacturers is clear international recognition of the company’s excellence in launch services. Because of its reliability and availability, the Arianespace launch system continues to set the global standard. Ariane 5 is the only commercial satellite launcher now on the market capable of simultaneously launching two payloads. Over the last two decades, Arianespace and SES have developed an exceptional relationship. ASTRA 3B will be the 33rd satellite from the SES group (Euronext Paris and Luxembourg Bourse: SESG) to have chosen the European launcher. SES ASTRA operates the leading direct-to-home TV broadcast system in Europe, serving more than 125 million households via DTH and cable networks. ASTRA 3B was built by Astrium using a Eurostar E 3000 platform, and will weigh approximately 5,500 kg at launch. Fitted with 60 active Ku-band transponders and four Ka-band transponders, ASTRA 3B will be positioned at 23.5 degrees East. It will deliver high-power broadcast services across all of Europe, and offers a design life of 15 years. Astrium chose Arianespace for the launch of two military communications satellites, COMSATBw-1 and COMSATBw-2, as part of a satellite communications system supplied to the German Ministry of Defense. The first satellite in this family, COMSATBw-1, was launched by Arianespace in October 2009. -

IT's a Little Chile up Here

IT’s A Little chile up here Press Kit | NET 29 July 2021 LAUNCH INFORMATION LAUNCH WINDOW ORBIT 12-day launch window opening from 29 July 2021 600km DAILY LAUNCH OPPORTUNITY The launch timing for this mission is the same for each day of the launch window. SATELLITES Time Zone Window Open Window Close NZT 18:00 20:00 UTC 06:00 08:00 1 EDT 02:00 04:00 PDT 23:00 01:00 The launch window extends for 12 days. INCLINATION 37 Degrees LAUNCH SITE Launch Complex 1, Mahia, New Zealand CUSTOMER LIVE STREAM Watch the live launch webcast: USSF rocketlabusa.com/live-stream Dedicated mission for U.S. Space Force 2 | Rocket Lab | Press Kit: It’s A Little Chile Up Here Mission OVERVIEW About ‘It’s a Little Chile Up Here’ Electron will launch a research and development satellite to low Earth orbit from Launch Complex 1 in New Zealand for the United States Space Force COMPLEX 1 LAUNCH MAHIA, NEW ZEALAND Electron will deploy an Air Force Research Laboratory- sponsored demonstration satellite called Monolith. ‘It’s a Little Chile Up Here’ The satellite will explore and demonstrate the use of a deployable sensor, where the sensor’s mass is a will be Rocket Lab’s: substantial fraction of the total mass of the spacecraft, changing the spacecraft’s dynamic properties and testing ability to maintain spacecraft attitude control. Analysis from the use of a deployable sensor aims to th st enable the use of smaller satellite buses when building 4 21 future deployable sensors such as weather satellites, launch for Electron launch thereby reducing the cost, complexity, and development timelines. -

Press Release

Rocket Lab, an End-to-End Space Company and Global Leader in Launch, to Become Publicly Traded Through Merger with Vector Acquisition Corporation End-to-end space company with an established track record, uniquely positioned to extend its lead across a launch, space systems and space applications market forecast to grow to $1.4 trillion by 2030 One of only two U.S. commercial companies delivering regular access to orbit: 97 satellites deployed for governments and private companies across 16 missions Second most frequently launched U.S. orbital rocket, with proven Photon spacecraft platform already operating on orbit and missions booked to the Moon, Mars and Venus Transaction will provide capital to fund development of reusable Neutron launch vehicle with an 8-ton payload lift capacity tailored for mega constellations, deep space missions and human spaceflight Proceeds also expected to fund organic and inorganic growth in the space systems market and support expansion into space applications enabling Rocket Lab to deliver data and services from space Business combination values Rocket Lab at an implied pro forma enterprise value of $4.1 billion. Pro forma cash balance of the combined company of approximately $750 million at close Rocket Lab forecasts that it will generate positive adjusted EBITDA in 2023, positive cash flows in 2024 and more than $1 billion in revenue in 2026 Group of top-tier institutional investors have committed to participate in the transaction through a significantly oversubscribed PIPE of approximately $470 million, with 39 total investors including Vector Capital, BlackRock and Neuberger Berman Transaction is expected to close in Q2 2021, upon which Rocket Lab will be publicly listed on the Nasdaq under the ticker RKLB Current Rocket Lab shareholders will own 82% of the pro forma equity of combined company Long Beach, California – 1 March 2021 – Rocket Lab USA, Inc. -

2019 Nano/Microsatellite Market Forecast, 9Th Edition

2019 NANO/MICROSATELLITE MARKET FORECAST, 9TH EDITION Copyright 2018, SpaceWorks Enterprises, Inc. (SEI) APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE. SPACEWORKS ENTERPRISES, INC., COPYRIGHT 2018. 1 Since 2008, SpaceWorks has actively monitored companies and economic activity across both the satellite and launch sectors 0 - 50 kg 50 - 250kg 250 - 1000kg 1000 - 2000kg 2000kg+ Custom market assessments are available for all mass classes NANO/MICROSATELLITE DEFINITION Picosatellite Nanosatellite Microsatellite Small/Medium Satellite (0.1 – 0.99 kg) (1 – 10 kg) (10 – 100 kg) (100 – 1000 kg) 0 kg 1 kg 10 kg 100 kg 1000 kg This report bounds the upper range of interest in microsatellites at 50 kg given the relatively large amount of satellite development activity in the 1 – 50 kg range FORECASTING METHODOLOGY SpaceWorks’ proprietary Launch Demand Database (LDDB) Downstream serves as the data source for all satellite market Demand assessments ▪ Planned The LDDB is a catalogue of over 10,000+ historical and Constellations future satellites containing both public and non-public (LDDB) satellite programs Launch Supply SpaceWorks newly updated Probabilistic Forecast Model (PFM) is used to generate future market potential SpaceWorks PFM Model ▪ The PFM considers down-stream demand, announced/planed satellite constellations, and supply-side dynamics, among other relevant factors Expert Analysis The team of expert industry analysts at SpaceWorks SpaceWorks further interprets and refines the PFM results to create Forecast accurate market forecasts Methodology at a Glance 2018 SpaceWorks forecasted 2018 nano/microsatellite launches with unprecedented accuracy – actual satellites launched amounted to just 5% below our analysts’ predictions. In line with SpaceWorks’ expectations, the industry corrected after a record launch year in 2017, sending 20% less nano/microsatellites to orbit than in 2018. -

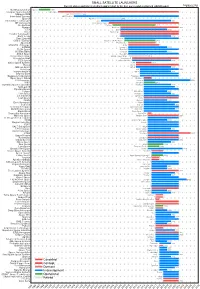

Small Satellite Launchers

SMALL SATELLITE LAUNCHERS NewSpace Index 2020/04/20 Current status and time from development start to the first successful or planned orbital launch NEWSPACE.IM Northrop Grumman Pegasus 1990 Scorpius Space Launch Demi-Sprite ? Makeyev OKB Shtil 1998 Interorbital Systems NEPTUNE N1 ? SpaceX Falcon 1e 2008 Interstellar Technologies Zero 2021 MT Aerospace MTA, WARR, Daneo ? Rocket Lab Electron 2017 Nammo North Star 2020 CTA VLM 2020 Acrux Montenegro ? Frontier Astronautics ? ? Earth to Sky ? 2021 Zero 2 Infinity Bloostar ? CASIC / ExPace Kuaizhou-1A (Fei Tian 1) 2017 SpaceLS Prometheus-1 ? MISHAAL Aerospace M-OV ? CONAE Tronador II 2020 TLON Space Aventura I ? Rocketcrafters Intrepid-1 2020 ARCA Space Haas 2CA ? Aerojet Rocketdyne SPARK / Super Strypi 2015 Generation Orbit GoLauncher 2 ? PLD Space Miura 5 (Arion 2) 2021 Swiss Space Systems SOAR 2018 Heliaq ALV-2 ? Gilmour Space Eris-S 2021 Roketsan UFS 2023 Independence-X DNLV 2021 Beyond Earth ? ? Bagaveev Corporation Bagaveev ? Open Space Orbital Neutrino I ? LIA Aerospace Procyon 2026 JAXA SS-520-4 2017 Swedish Space Corporation Rainbow 2021 SpinLaunch ? 2022 Pipeline2Space ? ? Perigee Blue Whale 2020 Link Space New Line 1 2021 Lin Industrial Taymyr-1A ? Leaf Space Primo ? Firefly 2020 Exos Aerospace Jaguar ? Cubecab Cab-3A 2022 Celestia Aerospace Space Arrow CM ? bluShift Aerospace Red Dwarf 2022 Black Arrow Black Arrow 2 ? Tranquility Aerospace Devon Two ? Masterra Space MINSAT-2000 2021 LEO Launcher & Logistics ? ? ISRO SSLV (PSLV Light) 2020 Wagner Industries Konshu ? VSAT ? ? VALT -

NASA Expendable Launch Services Current Use of EELV

NASA Expendable Launch Services Current Use of EELV Lynn F. H. Cline Deputy Associate Administrator for Space Operations National Aeronautics and Space Administration June 17, 2009 Overview • NASA’s expendable launch vehicles are run by the Launch Services Program (LSP) consolidated at Kennedy Space Center in 1998 – LSP provides acquisition, technical management, mission integration and launch management • NASA utilizes a mixed fleet of vehicles (small, medium & intermediate) with varying levels of performance used to support a mix of mission sizes – Mainly for Science Mission Directorate payloads, but other NASA Directorates and other government agencies also use NASA launch services – Launches conducted from multiple ranges, including RTS, WFF, Kodiak • Vehicles are selected from the NASA Launch Services Contract (NLS) – Through competition based on mass, orbit, class of payload, and best value – Current NLS contract expires in 2010, RFP released to extend the contract • Most recent contract action purchased four intermediate class missions – TDRS – K & L, RBSP and MMS • Important issues – Loss of Medium Class launch service provider, which has been 50% of NASA missions historically – Compressed manifest – Possibility that NASA incurs a portion of the intermediate class infrastructure costs post 2010 NASA Launch Services Manifest FPB Approved 3/25/09 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Release 6/03/09 Rev. 1 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Small Class (SC) NuSTAR (P-XL) -

Space Coast Is Getting Busy: 6 New Rockets Coming to Cape Canaveral, KSC

4/16/2019 Space Coast is getting busy: 6 new rockets coming to Cape Canaveral, KSC Space Coast is getting busy: 6 new rockets coming to Cape Canaveral, Kennedy Space Center Emre Kelly, Florida Today Published 4:04 p.m. ET April 11, 2019 | Updated 7:53 a.m. ET April 12, 2019 COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. – If schedules hold, the Space Coast will live up to its name over the next two years as a half-dozen new rockets target launches from sites peppered across the Eastern Range. Company, government and military officials here at the 35th Space Symposium, an annual space conference, have reaffirmed their plans to launch rockets ranging from more traditional heavy-lift behemoths to smaller vehicles that take advantage of new manufacturing technologies. Even if some of these schedules slip, at least one thing is apparent to several spaceflight experts here: The Eastern Range is seeing an unprecedented growth in commercial space companies and efforts. Space Launch System: 2020 NASA's Space Launch System rocket launches from Kennedy Space Center's pad 39B in this rendering by the agency. (Photo: NASA) NASA's long-awaited SLS, a multibillion-dollar rocket announced in 2011, is slated to become the most powerful launch vehicle in history if it can meet a stringent late 2020 deadline. The 322-foot-tall rocket is expected to launch on its first flight – Exploration Mission 1 – from Kennedy Space Center with an uncrewed Orion capsule for a mission around the moon, which fits in with the agency's wider goal of putting humans on the surface by 2024. -

Launcherone Success Opens New Space Access Gateway Guy Norris January 22, 2021

1/22/21 7:05 1/6 LauncherOne Success Opens New Space Access Gateway Guy Norris January 22, 2021 With San Nicolas Island far below, LauncherOne headed for polar orbit. Credit: Virgin Orbit Virgin Orbit had barely tweeted news of the successful Jan. 17 space debut of its LauncherOne vehicle on social media when new launch contracts began arriving in the company’s email inbox. A testament to the pent-up market demand for small-satellite launch capability, the speedy reaction to the long-awaited demonstration of the new space-access vehicle paves the way for multiple follow-on Virgin Orbit missions by year-end and a potential doubling of the rate in 2022. First successful privately developed air-launched, liquid-fueled rocket Payloads deployed for NASA’s Venture Class Launch Services program The glitch-free !ight of LauncherOne on its second demonstration test was a critical and much-welcomed milestone for the Long Beach, California-based company. Coming almost nine years a"er the air-launch concept was #rst unveiled by Virgin founder Richard Branson, and six years a"er the start of full-scale development, the !ight followed last May’s #rst demonstration mission, which ended abruptly when the rocket motor shut o$ a"er just 4 sec. 1/22/21 7:05 2/6 A"er an exhaustive analysis and modi#cations to beef up the oxidizer feed line at the heart of the #rst !ight failure, the path to the Launch Demo 2 test was then delayed until January 2021 by the COVID-19 pandemic. With the LauncherOne system now proven, design changes veri#ed and the #rst 10 small satellites placed in orbit, Virgin Orbit is already focusing on the next steps to ramp up its production and launch-cadence capabilities. -

Photographs Written Historical and Descriptive

CAPE CANAVERAL AIR FORCE STATION, MISSILE ASSEMBLY HAER FL-8-B BUILDING AE HAER FL-8-B (John F. Kennedy Space Center, Hanger AE) Cape Canaveral Brevard County Florida PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD SOUTHEAST REGIONAL OFFICE National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 100 Alabama St. NW Atlanta, GA 30303 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD CAPE CANAVERAL AIR FORCE STATION, MISSILE ASSEMBLY BUILDING AE (Hangar AE) HAER NO. FL-8-B Location: Hangar Road, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (CCAFS), Industrial Area, Brevard County, Florida. USGS Cape Canaveral, Florida, Quadrangle. Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: E 540610 N 3151547, Zone 17, NAD 1983. Date of Construction: 1959 Present Owner: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Present Use: Home to NASA’s Launch Services Program (LSP) and the Launch Vehicle Data Center (LVDC). The LVDC allows engineers to monitor telemetry data during unmanned rocket launches. Significance: Missile Assembly Building AE, commonly called Hangar AE, is nationally significant as the telemetry station for NASA KSC’s unmanned Expendable Launch Vehicle (ELV) program. Since 1961, the building has been the principal facility for monitoring telemetry communications data during ELV launches and until 1995 it processed scientifically significant ELV satellite payloads. Still in operation, Hangar AE is essential to the continuing mission and success of NASA’s unmanned rocket launch program at KSC. It is eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) under Criterion A in the area of Space Exploration as Kennedy Space Center’s (KSC) original Mission Control Center for its program of unmanned launch missions and under Criterion C as a contributing resource in the CCAFS Industrial Area Historic District.