California State University, Northridge Past Into Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religious Advisement Resources Part Ii

RELIGIOUS ADVISEMENT RESOURCES 2020 PART II Notice Regarding External Resources: The listed resources are provided in this document are operated by other government organizations, commercial firms, educational institutions, and private parties. We have no control over the information of these resources which may contain information that could be objectionable or which may not otherwise conform to Department of Defense policies. These listings are offered as a convenience and for informational purposes only. Their inclusion here does not constitute an endorsement or an approval by the Department of Defense of any of the products, services, or opinions of the external providers. The Department of Defense bears no responsibility for the accuracy or the content of these resources. 1 FAITH AND BELIEF SYSTEMS U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Prisons Inmate Religious Beliefs and Practices http://www.acfsa.org/documents/dietsReligious/FederalGuidelinesInmateReligiousBeliefsandPractices032702.pdf Buddhism Native American Eastern Rite Catholicism Odinism/Asatru Hinduism Protestant Christianity Islam Rastfari Judaism Roman Catholic Christianity Moorish Science Temple of America Sikh Dharma Nation of Islam Wicca U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Religious Literacy Primer https://crcc.usc.edu/files/2015/02/Primer-HighRes.pdf Baha’i Earth-Based Spirituality Buddhism Hinduism Christianity: Anabaptist Humanism Anglican/Episcopal Islam Christian Science Jainism Evangelical Judaism Jehovah’s Witnesses -

Mexico - the Country 1

Mexico - The Country 1. 758,278 square miles in size. 2. 1,100 miles long ••••• 1,900 miles wide. 3. One-Fourth the size of the United States. 4. 2,000 miles of border with the United States. 5. Two-Thirds of the country is mountains or desert: A) The geography has created some bad \ economic problems. B) It has created difficulties in transportation. C) It has created difficulties in communication. 6. Also has: A) Fertile plains. B) Tropical areas. C) Rivers••••• Etc. 7. Highest point in the country••• Mt. Orizaba: A) 18,700 feet high. ( 8. Annual average temperature••••• 62 degrees. / \, 9. Primary Barrier to••••• Economic "Well-Being"••••• Absence of sufficient moisture: A) Northern Mexico••••• Parched - "Water Hungry." B) Central Mexico••••• Barely enough moisture to sustain plant life: I. Rains are seasonal! C) Southern Mexico••••• Saturated with water. 10. Rain: A) One-Half of the country: I. Insufficient rain year-round. B) 130/0 of the country: I. Sufficient rain year-round. 11. Permanent Snow Line: A) Between 14,600 and 15,000 feet. 12. Is a country of small villages: A) 940/0 of these villages have less than 500 people. 13. Capital ••• Mexico City••• 7 ,650 feet above sea level: A) Largest city. B) From Mexico City to Veracruz ••• 265 miles. 14. 2 nd largest city••• Guadalajara. 15. 3 rd largest city••• Monterrey. 16. 4th largest city••• Puebla. 17. 21 cities ••• Population of 25,000 or more. 18. Population: A) Density is over 27 per square mile. B) 70% live above 3,000 feet sea level. C) 29% live above 6,000 feet sea level. -

Ancient Cultures

Name: Date: Mesoamerica Quiz Class: 1. What can you conclude about Mesoamerica from its 6. What did Maya civilization have in common with name? Western civilization? a. Its political structure a. The development of a written language b. The types of languages spoken there b. The domestication of horses and cattle c. The time period when great civilizations flourished c. The use of a 12-month calendar there d. The worship of a single, all-powerful god d. Its location 7. What is cultural diffusion? Choose the best answer. 2. Where could you visit if you a. When one culture takes over and completely replaces wanted to see ancient an existing culture Mesoamerican ruins? b. The spreading and sharing of cultural ideas between societies that are close together c. The weakening of traditional culture in the face of a. Texas modernization b. Argentina d. When several independent societies are united into a c. Guatemala single large empire d. Peru 8. What role did maize play in 3. Are the Spanish-speaking populations of Mexico, Mesoamerican culture? Spain, and Peru a culture area? a. Yes, because the people in these places all speak Spanish b. No, because the three areas are not geographically a. It was a staple of the Mesoamerican diet connected b. It was used only to feed domesticated animals c. No, because there are no similarities shared by these c. It played only a ceremonial role in Mesoamerican three cultures culture d. Yes, because the people in these places all practice d. It was the only crop Mesoamericans knew how to the same religion grow 4. -

Christianity, Islam, and Judaism Are All Monotheistic Religions Founded in the Middle East

Christianity, Islam, and Judaism are all monotheistic religions founded in the Middle East. Often grouped together as “Abrahamic religions," these three faiths share common history and traditions, a respect for the Bible, a conviction that there is one God, a belief in prophets and divine revelation, and a holy city in Jerusalem, among other things. But Christianity, Islam and Judaism also differ significantly in matters of belief and practice, from their understanding of God to the identity of the prophets and Jesus and the authority of various scriptures. The following chart is intended to be a starting point for understanding these ancient religions and their relationships to one another. Christianity Islam Judaism origins Based on life and teachings of Jesus of Based on teachings of the Prophet The religion of the Hebrews (c. 1300 Nazareth, c. 30 CE, Roman province Muhammad; founded 622 CE in BC), especially after the destruction of of Palestine. Mecca, Saudi Arabia. the Second Temple in 70 AD. major splits Catholic-Orthodox (1054); Catholic- Shia-Sunni (c. 650 CE) Reform-Orthodox (1800s CE) Protestant (1500s) original Aramaic and Greek Arabic Hebrew language adherents 2 billion 1.3 billion 14 million texts Bible (Hebrew Bible + New Qur'an (Scripture); Hadith (tradition) Hebrew Bible (Tanakh); Talmud Testament) god(s) Holy Trinity = God the Father + God One God (Allah in Arabic); the same One God: Yahweh (YHVH) God revealed (imperfectly) in the Christianity Islam Judaism the Son + God the Holy Spirit Jewish and Christian Bibles Jesus was Son of God. Savior. Messiah. Second True prophet sent by God, but message false prophet person of the Trinity. -

A Linguistic Look at the Olmecs Author(S): Lyle Campbell and Terrence Kaufman Source: American Antiquity, Vol

Society for American Archaeology A Linguistic Look at the Olmecs Author(s): Lyle Campbell and Terrence Kaufman Source: American Antiquity, Vol. 41, No. 1 (Jan., 1976), pp. 80-89 Published by: Society for American Archaeology Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/279044 Accessed: 24/02/2010 18:09 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sam. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society for American Archaeology is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Antiquity. http://www.jstor.org 80 AMERICAN ANTIQUITY [Vol. 41, No. 1, 1976] Palomino, Aquiles Smith, Augustus Ledyard, and Alfred V. -

Encounter with the Plumed Serpent

Maarten Jansen and Gabina Aurora Pérez Jiménez ENCOUNTENCOUNTEERR withwith thethe Drama and Power in the Heart of Mesoamerica Preface Encounter WITH THE plumed serpent i Mesoamerican Worlds From the Olmecs to the Danzantes GENERAL EDITORS: DAVÍD CARRASCO AND EDUARDO MATOS MOCTEZUMA The Apotheosis of Janaab’ Pakal: Science, History, and Religion at Classic Maya Palenque, GERARDO ALDANA Commoner Ritual and Ideology in Ancient Mesoamerica, NANCY GONLIN AND JON C. LOHSE, EDITORS Eating Landscape: Aztec and European Occupation of Tlalocan, PHILIP P. ARNOLD Empires of Time: Calendars, Clocks, and Cultures, Revised Edition, ANTHONY AVENI Encounter with the Plumed Serpent: Drama and Power in the Heart of Mesoamerica, MAARTEN JANSEN AND GABINA AURORA PÉREZ JIMÉNEZ In the Realm of Nachan Kan: Postclassic Maya Archaeology at Laguna de On, Belize, MARILYN A. MASSON Life and Death in the Templo Mayor, EDUARDO MATOS MOCTEZUMA The Madrid Codex: New Approaches to Understanding an Ancient Maya Manuscript, GABRIELLE VAIL AND ANTHONY AVENI, EDITORS Mesoamerican Ritual Economy: Archaeological and Ethnological Perspectives, E. CHRISTIAN WELLS AND KARLA L. DAVIS-SALAZAR, EDITORS Mesoamerica’s Classic Heritage: Teotihuacan to the Aztecs, DAVÍD CARRASCO, LINDSAY JONES, AND SCOTT SESSIONS Mockeries and Metamorphoses of an Aztec God: Tezcatlipoca, “Lord of the Smoking Mirror,” GUILHEM OLIVIER, TRANSLATED BY MICHEL BESSON Rabinal Achi: A Fifteenth-Century Maya Dynastic Drama, ALAIN BRETON, EDITOR; TRANSLATED BY TERESA LAVENDER FAGAN AND ROBERT SCHNEIDER Representing Aztec Ritual: Performance, Text, and Image in the Work of Sahagún, ELOISE QUIÑONES KEBER, EDITOR The Social Experience of Childhood in Mesoamerica, TRACI ARDREN AND SCOTT R. HUTSON, EDITORS Stone Houses and Earth Lords: Maya Religion in the Cave Context, KEITH M. -

A Conference in Pre-Columbian Iconography Elizabeth P. Benson

A Conference in Pre-Columbian Iconography OCTOBER 3l ST AND NOVEMBER l ST, 1970 Elizabeth P. Benson, Editor Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collections TRUSTEES FOR HARVARD UNIVERSITY Washington, D.C. Copyright 1972 Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C. Library of Congress catalog number 72-90080 Preface OBERT WOODS BLISS began collecting Pre-Columbian art because he was lured by the beauty of the materials, the fineness of the craftsmanship, and Rthe fascination of the iconography of the first Pre-Columbian objects he saw. The Bliss Collection has been, since its beginning in 1912, primarily an esthetic one-probably the first esthetically oriented collection of Pre-Columbian artifacts- so it seemed appropriate to organize a conference that would focus on a cross-cultural, art-historical approach. When we sought for a theme, the first that came to mind was that great unifying factor in Pre-Columbian cultures, the feline. Large cats such as the jaguar and puma preoccupied the artists and religious thinkers of the very earliest civilizations, the Olmec in Mesoamerica and Chavín in Peru. The feline continued to be an important theme throughout much of the New World until the European con- quests. We are indebted to Barbara Braun for the title, “The Cult of the Feline.” Pre-Columbian studies merge many disciplines. This conference was not only cross- cultural but cross-disciplinary-with contributions from anthropologists, archaeolo- gists, art historians, and ethnologists-since we believed that the art-historical ap- proach to iconography should be based on the knowledge of what has been found archaeologically and what is known of the customs of the present-day peoples who have been isolated enough to carry on what must be very ancient traditions. -

California State University, Northridge the Were

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE THE WERE-JAGUAR MOTIF AND THE OLMEC CHIEFDOM A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the .requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology by Bryn Marie Barabas January 1985 0 • The Thesis of Bryn Marie Barabas is approved: Susan Kenagy Dav~ Hayanbj f{_ Robert Ravicz, Chairma~ California State University, Northridge ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to gratefully acknowledge all of the help and guidance provided by my committee members, Susan Kenagy, David Hayano, Robert Ravicz, and my second ·chair Carol Mackey, without whom this thesis wo~ld not have been possible. I also extend thanks to Gregory Truex, Charles Bearchell, and Ralph Vicero for coming through in the end. Thanks Mom and Pops for your patient understanding and encouragement. And finally, multiple thank yous to all of those special people, particularly R. J., for seeing me through with my elusive were-jaguar dream. iii TABLE ·oF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • • • • • • • • • • • • iii LIST OF FIGURES • • • • • • • • • • • • v ABSTRACT • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • vi Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • 1 2 DEFINITIONS • • • • • • • • • • 5 Summary • • • • • • • • • • 14 3 BACKGROUND • • • • • • • • • • 16 Summary • • • • • • • • • • 36 4 THE WERE-JAGUAR • • • • • • • • • 38 Summary • • • • • • • • • • 71 5 SAN LORENZO • • • • • • • • • • 73 Summary • • • .. • • • • • • 86 6 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS • _. • • • • 89 Conclusions • • • • • • • • • 93 NOTES • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 97 FIGURES • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 99 REFERENCES • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 117 APPENDIX • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 130 iv LIST OF FIGURES figure page 1 The Olmec Area (Weaver 1981:63). • • • • • • 100 2 Chronology (Coe 1970; Tolstoy 1978; Weaver 1981) • 101 3 Olmec Central Places (Bernal 1969; Bove 1976:129). 102 4 Celts or Ceremonial Axes (Covarrubias 1946:30). • 103 5 Evolution of Mesoamerican Rain Gods (Covarrubias 1946:27) ~ • • • • • • • • • 104 6 R{o Chiquita Monument 1 (Joralemon 1976:31). -

The Olmec, Maya & Aztec

The Olmec, Maya & Aztec Mesoamerica • Mesoamerica refers to a geographical and cultural area which extends from central Mexico down through Central America. • The term “Meso” means middle. (Middle America) • Many important Ancient Civilizations developed in this area. • A civilization is a culture that has developed complex systems of government, education, and religion. Mesoamerica The Original Olmec Olmec Civilization • The Olmec civilization existed from 1300 BC to about 400 BC. • The Olmec are believed to be the earliest civilization in the Americas. • The Olmec people established a civilization in the area we know today as southern Mexico. Map of Olmec Empire: The “Mother Culture” • Many historians consider the Olmec civilization the “mother culture” of Mesoamerica. • A mother culture is a way of life that strongly influences later cultures. • The Olmec empire led to the development of other civilizations, such as the Maya and the Aztec. Olmec Daily Life • The Olmec were very good at farming. The land in this region was very fertile and food supply was steady. • They lived in villages near rivers and also fished for food. • Olmec people also were good at making pottery and weaving. Olmec Daily Life • The Olmec played a game called “pok-a-tok” where, you must shoot a rubber ball through a stone ring without using your hands or feet. • Huge ball courts built by the Olmec suggest that the game was popular with spectators. Olmec Art • The Olmec carved large heads from basalt, a type of volcanic rock. • What the giant stone heads represent or why the Olmec built them is a mystery. -

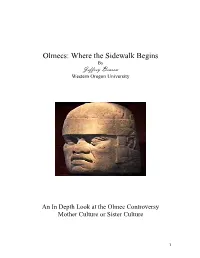

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins by Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins By Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University An In Depth Look at the Olmec Controversy Mother Culture or Sister Culture 1 The discovery of the Olmecs has caused archeologists, scientists, historians and scholars from various fields to reevaluate the research of the Olmecs on account of the highly discussed and argued areas of debate that surround the people known as the Olmecs. Given that the Olmecs have only been studied in a more thorough manner for only about a half a century, today we have been able to study this group with more overall gathered information of Mesoamerica and we have been able to take a more technological approach to studying the Olmecs. The studies of the Olmecs reveals much information about who these people were, what kind of a civilization they had, but more importantly the studies reveal a linkage between the Olmecs as a mother culture to later established civilizations including the Mayas, Teotihuacan and other various city- states of Mesoamerica. The data collected links the Olmecs to other cultures in several areas such as writing, pottery and art. With this new found data two main theories have evolved. The first is that the Olmecs were the mother culture. This theory states that writing, the calendar and types of art originated under Olmec rule and later were spread to future generational tribes of Mesoamerica. The second main theory proposes that the Olmecs were one of many contemporary cultures all which acted sister cultures. The thought is that it was not the Olmecs who were the first to introduce writing or the calendar to Mesoamerica but that various indigenous surrounding tribes influenced and helped establish forms of writing, a calendar system and common types of art. -

Interpreting Olmec Style Symbolism at the Formative

THE DAWNING OF CREATION IN THE CENTRAL MEXICAN HIGHLANDS: INTERPRETING OLMEC STYLE SYMBOLISM AT THE FORMATIVE PERIOD SITES OF CHALCATZINGO, OXTOTITLÁN, AND JUXTLAHUACA by Brendan C. Stanley, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in Anthropology August 2020 Committee Members F. Kent Reilly III, Chair David A. Freidel Jim F. Garber COPYRIGHT by Brendan C. Stanley 2020 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-533, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Brendan C. Stanley, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for education or scholarly purposes only. ACKNOWLEDEGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude towards my committee members, David A. Freidel and Jim F. Garber, for their guidance and support throughout the writing process. I would especially like to thank my committee chair, long time mentor, and friend, F. Kent Reilly III, for all the support and assistance throughout the past years. This thesis would not have been possible without all your help. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................. -

Guerrero's Archaeological

Guerrero’s Archaeological Patrimony and Cultural Potential Gerardo Gutiérrez* l e i t n o M e i s l E y b s o t o h P Teopantecuanitlan Cuetlajuchitlan iven a random combination of factors including difficult topography, a lack Gof paved highways and certain social strife, until very recently, archaeological re - search in Guerrero was minimal. Despite the efforts of a dozen or so Mexican and foreign archaeologists who fought day to day to sal - vage and disseminate the state’s rich archaeo - logical patrimony, the lack of exploration is evi - Xochipala dent. This turns the archaeology of Guerrero into a big black box: all kinds of unproven idea s fit. Thus, the cultures that inhabited Guerrero Colima, Jalisco, Michoacán and Nayarit have have been classified as peripheral, marginal, non - begun to leave Guerrero out of this regional urban, pre-state, etc. But, actually, the state’s classification because they consider it different archaeological remains show patterns of de - from what is called the West. Unfortunately, velopment similar to the rest of Mesoamerica important museums continue to promote this and in the same time period, which means the y idea: for example, the National Anthropology are not backward, or marginal or peripheral. Museum’s Room of Western Cultures exhibits In 1948, the Mexican Anthropological So - an important collection of archaeological ob - ciety classified the state of Guerrero as part of jects from Guerrero, together with shaft tombs the cultural region called the Mexican West. from the states of Colima and Jalisco, and cave Although this erroneous notion can still be art from the northern state of Baja California! found in the literature, specialists working in This arrangement would not be particularly pro b - lematic if it were not for the fact that Gue - rrero’s archaeological material shows evidence * Archaeologist and ethno-historian.