With Special Reference to the Ornamental Prefix O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In This Issue

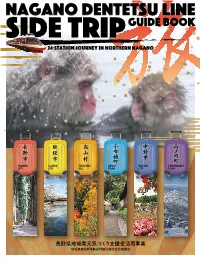

to Kanazawa In this issue to JoetsuJCT Toyoda-Iiyama I.C P.12 Nakano City Shinsyu-Nakano I.C P.14 Yudanaka Station Shinsyu-Nakano P.04 P.10 Station Nagano Yamanouchi Town Nagano City Obuse Town Snow Monkey Obuse Dentetsu Station Line Obuse P.A P.08 Suzaka Station Takayama Vill Nagano Zenkoji Temple Station P.06 Nagano I.C Expressway Suzaka City Nagano Expressway Joshinetsu Koshoku J.C.T Nagano Prefecture Nagano City Suzaka City Greetings from Northern 1Zenkoji × Soba× Oyaki p04 2 What´s Misosuki Don ? p06 Nagano! Come take a JoshinetsuExpressway Shinshu Matsumoto Airport Mathumoto I.C JR Hokuriku Shinkansen to Tokyo journey of 24 stations ! 02 Enjoy a scenic train ride through the 03 Nagano Hongo Kirihara Kamijyo Hino Kita-suzaka Entoku Nakano-Matsukawa Fuzokuchugakumae Murayama Shiyakushomae Shinano-Yoshida Suzaka Sakurasawa Shinsyu-Nakano Shinano-Takehara Gondo Obuse Zenkojishita Asahi Tsusumi Yomase Yudanaka Yanagihara Nagano countryside on the Nagano Dentetsu line. Nicknamed “Nagaden”, min 2 min 2 min 2 min 2 min 2 min 2 min 3 min 2 min 2 min 3 min 2 min 3 min 4 min 4 min 2 min 4 min 3 min 4 min 3 min 4 min 2 min 2 min 3 the train has linked Nagano City with Suzaka, Obuse, Nakano and Yamanouchi since it opened in 10- June, 1922. Local trains provide min 2 min 2 min 3 min 2 min 3 min 8 min 6 min 9 12min Limited B express leisurely service to all 24 stations min 2 14min min 6 min 9 12min along the way, while the express trains Limited A express such as the “Snow Monkey” reaches Takayama Village Obuse Town 【About express train 】 Yudanaka from Nagano Station in as quickly as 44 minutes. -

GOHAN「 Rice 」 OKAZU

“DASHI” is a traditional stock of bonito skipjack tuna (katsuo) and konbu seaweed, making a broth brimming with umami, the savory fifth taste sensation. Enjoy a cultural taste of Japan through Ramen. ひのでやは日本古来の食文化の根本である かつおや昆布の“だし”の旨みを食材より存分に引き出し、 この街・サンフランシスコでも身近な日本食の一つ「ラーメン」を通じて和風のだし文化を皆様にお届けします。 YASAI 「 vegetables 」 OKAZU 「 side dish 」 Shishito Peppers 5 Gyoza ( 5pcs ) 7 lightly fried and coated in a savory dashi soy pork and chicken dumpling w/ dashi sauce glaze. 1 in 10 might be extra spicy ! Hinodeya Salad 8 Green Gyoza(5pcs) 7 Half Salad 5 vegetables and edamame dumpling w/sesame sauce organic mizuna mix w/ home made vegetable dressing Crispy Fried Yam 8 naga-imo potato lightly fried w/ sesame sauce OTSUMAMI 「 tapas 」 Gyouza Tebasaki ( stewed chicken wings ) 8 Edamame 4 traditional Japanese braised chicken wings Izakaya style snap peas snack Spicy Menma 4 young bamboo shoots in hot chili oil Oysters Fried 9 Takowasa 5 from Hiroshima Japan chopped raw octopus in a wasabi sauce Spicy Edamame 5 Kara-Age ( 5pcs ) 10 spicy and savory, cooked in a hot oil, Fried juicy boneless cage free organic chicken garlic, and dashi sauce 肉味噌(Niku Miso) 5 GOHAN 「 rice 」 chopped pork w/spicy Miso ,topping endive Aburi Chashu 7 Quinoa Small Rice Bowl 4 w/traditional konbu and shiitake dashi taste flame torched pork belly full of flavor and steamed rice and quinoa fragrance. garnished with green onions & sriracha = Indicates item is vegan/ can be made vegan vegan and non-vegan items prepared using same kitchen and equipment RAMEN Hinodeya Ramen ( House -

4 Analyse Des Bildes Der Bösartigen Alten Frauen in Der

4 Analyse des Bildes der bösartigen alten Frauen in der Edo- zeitlichen Trivialkultur 4.1 Allgemeine Charakteristika der trivialen Kulturproduktion 4.1.1 Inhalte und Darstellungsweisen: Fantastik, Zerstückelung, Sensa- tionslust, und ihr problematischer Realitätsbezug Kehren wir nun zu den Edo-zeitlichen Abwandlungen des Themas zurück, so muss zunächst gesagt werden, dass jene Genres der bürgerli- chen Kultur, der die in Kapitel 2 beschriebenen Werke mit ihren Figu- ren bösartiger, mörderischer alter Frauen zuzurechnen sind – sei es das weite Feld der Holzschnitte, die Heftchen-Literatur oder das Kabuki- und Puppentheater –, von der Forschung bislang nur unzureichend be- rücksichtigt worden sind, zumal was ihre Inhalte und Bezüge zur sozia- len Realität betrifft. Zwar sind Kabuki und Bunraku als Theaterformen Teil der Weltkultur geworden und haben, was Darstellungstechniken betrifft, westliche Theatermacher auf der Suche nach Auswegen aus einer gewissen Sackgasse beeinflusst, in die zu viel Realismus und Sachlichkeit das europäische Theater geführt zu haben schienen. Doch richtet sich dieses Interesse auf Aufführungspraxis und Ästhetik beider unterschiedlicher, wenn auch einander nahe stehender Gattungen. Inhaltliche Untersuchungen waren und bleiben eher selten, denn, wie es Faubion Bowers 1956 formulierte, kursieren vorwiegend zwei Mei- nungen über das Kabuki: „die eine, die der westlichen Besucher, lautet, dass der Inhalt nicht wichtig ist, weil Kabuki vor allem ein Spektakel ist; die andere, meist von Japanern geäußerte, besagt, dass -

Tustin-Menu-2021.6-Newsmall.Pdf

Drink Menu SAKE HONDA-YA Sake We have collaborated with HONDA-YA Sake (300ml) $13.00 "KINOKUNIYA BUNZAEMON" Hot Sake Small(150ml) $4.50 to create a smooth and fragrant Large(300ml) $7.50 sake with a gentle robust flavor. Sho Chiku Bai (300ml) Unfiltered $10.00 Type: Junmai (300ml) Kikusui“Perfect Snow” $19.00 Region: Wakayama $13.00 (300ml) Unfiltered Honda-ya Sake PREMIUM SAKE (Junmai) Yaemon Hizo Senkin Dassai 39 Kubota Junmai Daiginjo Otokoyama Kame no O Junmai Daiginjo Junmai Daiginjo 300ml Blue Junmai Daiginjo 720ml 720ml $22.00 Junmai Ginjo 720ml $65.00 $65.00 Fukushima 720ml $60.00 Yamaguchi Niigata $50.00 Tochigi Fukuoka Onikoroshi Kurosawa Otokoyama Kikusui Seishu Junmai Premium Junmai Junmai Ginjo Glass $7.50 Glass $8.50 Glass $10.50 Glass $11. 5 0 1.8L $70.00 1.8L $80.00 1.8L $95.00 720ml $55.00 Kyoto Nagano Hokkaido 1.8L $100.00 Niigata WINE/PLUM WINE/FLAVORED SAKE Glass 1/2L 1L Hana Pineapple Chardonnay $4.00 $10.00 $18.00 Glass $7.00 Merlot $4.00 $10.00 $18.00 750ml Bottle $28.00 Takara Plum Wine $ 5 . 0 0 $13.00 $24.00 Hana White Peach Beninanko $9.00 $70.00 (720ml Bottle) Plum Wine Glass $7.00 Corkage Fee (Wine Bottle 750ml Only)$15.00 Beninanko Plum Wine 750ml Bottle $28.00 SOFT DRINK NR: Non Refillable Coke, Diet Coke, Sprite $3.00 Melon Soda, Calpico, NR $2.50 Iced Tea (sweetened), Pink Lemonade Iced Oolong Tea, Iced Green Tea, Orange Juice Ramune Soda Bottle NR $3.00 Hot Green Tea $1.50 Starter EDAMAME . -

Recipe Books in North America

Greetings How have Japanese foods changed between generations of Nikkei since they first arrived in their adopted countries from Japan? On behalf of the Kikkoman Institute for International Food Culture (KIIFC), Mr. Shigeru Kojima of the Advanced Research Center for Human Sciences, Waseda University, set out to answer this question. From 2015 to 2018, Mr. Kojima investigated recipe books and conducted interviews in areas populated by Japanese immigrants, particularly in Brazil and North American, including Hawaii. His research results on Brazil were published in 2017 in Food Culture No. 27. In this continuation of the series, he focuses on North America. With the long history of Japanese immigration to North America, as well as Nikkei internments during WWII, the researcher had some concerns as to how many recipe books could be collected. Thanks to Mr. Kojima’s two intensive research trips, the results were better than expected. At a time of increasing digitization in publishing, we believe this research is both timely and a great aid in preserving historical materials. We expect these accumulated historical materials will be utilized for other research in the future. The KIIFC will continue to promote activities that help the public gain a deeper understanding of diverse cultures through the exploration of food culture. CONTENTS Feature Recipe Books in North America 3 Introduction Recipe Books Published by Buddhist Associations and Other Religious Groups 10 Recipe Books Published by Nikkei Associations (Excluding Religious Associations) 13 Mobile Kitchen Recipe Books 15 Recipe Books Published by Public Markets and Others 17 Books of Japanese Recipes as Ethnic Cuisine 20 Recipe Books as Handbooks for Living in Different Cultures 21 Hand-written Recipe Books 22 Summary Shigeru Kojima A research fellow at the Advanced Research Center for Human Sciences, Waseda University, Shigeru Kojima was born in Sanjo City, Niigata Prefecture. -

Food Byways: the Sugar Road by Masami Ishii

Vol. 27 No. 3 October 2013 Kikkoman’s quarterly intercultural forum for the exchange of ideas on food SPOTLIGHT JAPAN: JAPANESE STYLE: Ohagi and Botamochi 5 MORE ABOUT JAPANESE COOKING 6 Japan’s Evolving Train Stations 4 DELECTABLE JOURNEYS: Nagano Oyaki 5 KIKKOMAN TODAY 8 THE JAPANESE TABLE Food Byways: The Sugar Road by Masami Ishii This third installment of our current Feature series traces Japan’s historical trade routes by which various foods were originally conveyed around the country. This time we look at how sugar came to make its way throughout Japan. Food Byways: The Sugar Road From Medicine to Sweets to be imported annually, and it was eventually According to a record of goods brought to Japan from disseminated throughout the towns of Hakata China by the scholar-priest Ganjin (Ch. Jianzhen; and Kokura in what is known today as Fukuoka 688–763), founder of Toshodaiji Temple in Nara, Prefecture in northern Kyushu island. As sugar cane sugar is thought to have been brought here in made its way into various regions, different ways the eighth century. Sugar was considered exceedingly of using it evolved. Reflecting this history, in the precious at that time, and until the thirteenth 1980s the Nagasaki Kaido highway connecting the century it was used solely as an ingredient in the cities of Nagasaki and Kokura was dubbed “the practice of traditional Chinese medicine. Sugar Road.” In Japan, the primary sweeteners had been After Japan adopted its national seclusion laws maltose syrup made from glutinous rice and malt, in the early seventeenth century, cutting off trade and a sweet boiled-down syrup called amazura made and contact with much of the world, Nagasaki from a Japanese ivy root. -

Ichiju Sansai

Washoku was Registered by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Asset, But What is It? Contents The Four Characteristics of Washoku Culture Washoku was Registered by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Asset, But What is It? Diverse, fresh ingredients, The Four Characteristics of Washoku Culture and respect for their What is Washoku as Cuisine? individual flavors The land of Japan extends a Washoku Ingredients long way from north to south, • Rice, Vegetables, Seafood, Wagyu and is covered by an expressive expanse of nature through seas, Washoku Condiments mountains, and villages. Diverse ingredients with local roots are Dashi used in each part of the country, Fermented Condiments and preparation techniques and implements have developed to • Soy Sauce, Miso, Sake, Vinegar, Mirin, make the most of their flavors. Fish sauce Yakumi • Wasabi (Japanese horseradish), Shoga (ginger), Negi (green onions), Shiso (perilla), Yuzu (Japanese citron) Nutritional balance Washoku Style to support a healthy Ichiju sansai diet The diet based on ichiju sansai Cha-kaiseki and Kaiseki (one soup and three dishes) makes it easy to get a good Nihonshu (Japanese sake) nutritional balance, makes the most of the umami of dashi stock Wagashi (Japanese cakes) and Nihoncha and of fermented ingredients, (Japanese tea) and keeps down the intake of animal fats. That helps the Chopsticks and the Manners of Eating With Japanese people live long and Them resist obesity. • Ohashi • Manners of eating Expression of the beauty of nature and the changing seasons Dishes are decorated with items Definition such as seasonal flowers and leaves, and furnishings and “Washoku”, as registered by UNESCO, goes utensil are used that match beyond the food itself, referring to Japan’s the season. -

Menú Okazu Mayo 2021

Olio Extravergine di Oliva BIOLOGICO ITALIANO BY CHEF ERIK MALMSTEN DISPONIBLE Bibenda 2021 Italian Sommelier Association Nomina a ARGIANO como uno mejores aceites de oliva procedentes de la Toscana. “ A perfect example of Italian olive oil at its best” Bernardino Sani CEO/ Wine Maker, Argiano “A fantastic olive oil” Luca Gardini Mejor Sommelier del mondo 2010 NORDIC | JAPANESE CUISINE ANOCHE CUBRÍ MIS HIJOS DORMIDOS Y EL RUIDO DEL MAR. WATANABE HAKUSEN L UNC H M ENU | 1 2 : 0 0 p m a 4 : 0 0 p m C O R T E S Í A Nordic Miso Soup OPCIÓN I. S U S H I L U N C H Sashimi de Atún o Salmón Niguiri Mixto de Salmón, Atún y Camarón Veggies Tempura Sushi Maki (Rolls) o Riceless A elección Café - Té O P C I Ó N II. C OCIN A C A L I E N T E Shrimp Gyoza Tomato Dashi / Fennel / Dill Oil Mushroom Gyoza Dashi Trufado / Cebolla Encurtida Okazu Fried Rice Arroz Koshihikari / Shiitake / Cebolla / Egg / Arroz Inflado Camarón - Pato - Picaña - Salmón Café - Té O P C I Ó N III . M I X T O Sashimi de Atún o Salmón Niguiri Mixto Salmón, Atún y Camarón Veggies Tempura Okazu Fried Rice Arroz Koshihikari / Shiitake / Cebolla / Egg / Arroz Inflado Camarón - Pato - Picaña - Salmón Café - Té BEBI D A S A E L E C CIÓ N Copa Vino Tinto / Blanco Jarra de Sake RD$ 1, 450 + imp. SNACKS Edamame & Sea Salt 335 Edamame Okazu Style 335 Fire Kissed with Togarashi Squid Chicharrón & Yuzu Kewpie 250 Shishitos 490 Soya Ahumada / Limón / Furikake SASHIMI() Hamachi 795 Atún 495 Atún Blanco 495 Salmón 550 Pulpo 550 Carite 450 Sashimi Mixto Pescado (12 cortes) 725 3 Cortes de 4 Variedades -

Yamazato En Menu.Pdf

グランドメニュー Grand menu Yamazato Speciality Hiyashi Tofu Chilled Tofu Served with Tasty Soy Sauce ¥ 1,300 Agedashi Tofu Deep-fried Tofu with Light Soy Sauce 1,300 Chawan Mushi Japanese Egg Custard 1,400 Tori Kara-age Deep-fried Marinated Chicken 1,800 Nasu Agedashi Deep-fried Eggplant with Light Soy Sauce 2,000 Yasai Takiawase Assorted Simmered Seasonal Vegetables 2,200 Kani Kora-age Deep-fried Crab Shell Stuffed with Minced Crab and Fish Paste 2,800 Main Dish Tempura Moriawase Assorted Tempura ¥ 4,000 Yakiyasai Grilled Assorted Vegetables 2,600 Sawara Yuko Yaki Grilled Spanish Mackerel with Yuzu Flavor 3,000 Saikyo-yaki Grilled Harvest Fish with Saikyo Miso Flavor 3,200 Unagi Kabayaki Grilled Eel with Sweet Soy Sauce 7,800 Yakimono Grilled Fish of the Day current price Yakitori Assorted Chicken Skewers 2,200 Sukini Simmered Sliced Beef with Sukiyaki Sauce 8,500 Wagyu Butter Yaki Grilled Fillet of Beef with Butter Sauce 10,000 Rice and Noodle Agemochi Nioroshi Deep-fried Rice Cake in Grated Radish Soup ¥ 1,700 Tori Zosui Chicken and Egg Rice Porridge 1,300 Yasai Zosui Thin-sliced Vegetables Rice Porridge 1,300 Kani Zosui King Crab and Egg Rice Porridge 1,800 Yasai Udon Udon Noodle Soup with Vegetables 1,500 Yasai Soba Buckwheat Noodle Soup with Vegetables 1,500 Tempura Udon Udon Noodle Soup with Assorted Tempura 5,200 Tempura Soba Buckwheat Noodle Soup with Assorted Tempura 5,200 Tendon Tempura Bowl Served with Miso Soup and Pickles 5,200 Una-jyu Eel Rice in Lacquer Box Served with Miso Soup 8,800 A la Carte Appetizers Yakigoma Tofu Seared -

JCCH Supports Hawai'i National History Day Students

SPRING 2020 | VOL. 26, NO . 1 JCCH Supports Hawai‘i National History Day Students A documentary about music in the World War II internment camps was selected to represent Hawai‘i in the National History Day competition. The filmmakers (left to right): Marissa Kwon, Lily Lockwood, and Erin Nishi. PAGE 4 EXECUTIVE DIREctor’s MESSAGE MARCH 16, 2020 “ Aloha” is more than a word of greeting or farewell or a salutation. “Aloha” means mutual regard and affection and extends warmth in caring with no obligation in return. “Aloha” is the essence of relationships in which each person is important to every other person for collective existence. “Aloha” means to hear what is not said, to see what cannot be seen and to know the unknowable. – The LaW OF THE ALOHA SPIRIT, HAWai‘i REVISED STATUTES JCCH MISSION STATEMENT: Aloha has been on our minds as we face a virus Now more than ever we recognize the To be a vibrant resource, that has led to a global pandemic. We draw importance of finding new ways to carry out our strengthening our diverse inspiration from the stories that have been passed mission to be a vibrant resource, strengthening community by educating down to us about how, during challenging times, our diverse community by educating present present and future generations our community has pulled together, persevered, and future generations in the evolving Japanese in the evolving Japanese and — with the Aloha Spirit intact — survived. American experience in Hawai‘i. The JCCH American experience in As we face the present-day threat of the volunteers have begun meeting with staff Hawai‘i. -

Asianinspirations.Com.Au Back to Content 1 Asianinspirations.Com.Au Back to Content 2 FAST & FAB

asianinspirations.com.au Back to Content 1 asianinspirations.com.au Back to Content 2 FAST & FAB Nuoc Cham Crunchy Prawn Salad 12 Char Kueh Tiaw 27 Meryem Celik Adeline Crispy Skin Duck Breast with Spring Onions, Enoki & Hoisin Jus 13 Vermicelli Noodle Salad with Cantonese Chicken 28 Hope V (Fast & Fab Theme Winner) Kristy Caramel Tamarind Pork with Thai Red Jasmine Rice & White Peach Salad 14 Seared Scallops with Cha Soba & Ponzu 30 Glenda McDonnell Hang Tran Thai Panang Chicken 16 Tuna Tartare 31 Kiet Chueamrasri (Wok of Fame Winner) Hope V Thai Prawn Skewers 18 Honey-Soy Salmon with Rich Coconut Rice & Ginger Veggies 32 Adrian Dalzotto Mariana Valdez Massaman Steak & Salad 19 Pork and Vegetable San Choi Bao 34 Bronwyn Cawley Donna Keogh 10 Minute Noodles with Prawns & Chilli Oil 21 Chicken Katsu Curry 35 Andrea Geddes Lachlan Gluten Free Pork & Baby Pak Choy Stir Fry 22 Creamy Chilli Coconut Prawns 36 Paula Swan (Wok of Fame Winner) Brian Hung (Fast & Fab Theme Winner) Coconut & Mango Tapioca Breakfast Pot 23 Sushi Stack with Egg Floss & Spicy Mango Kewpie 37 Svetlana Desousa Kristy (Asian Inspirations’ Choice Winner) Opor Ayam Kuning (Pressure Cooker Javanese 25 Mixed Seafood Stir-Fried with Red Curry Paste 40 Turmeric-Infused Creamy Coconut Chicken Curry) Chawalit Teeranal Helen Agostino asianinspirations.com.au Back to Content 3 FAST & FAB Korean Kimchi Pork 41 Mel A Mea Culpa Blackened Ocean Trout 42 Elizabeth Slee Fried Shrimp Dumpling 43 Jade (Fast & Fab Theme Winner) Okonomiyaki 44 Karl McKeever (Wok of Fame Winner) Bouquet of -

L J K C F I O B E H N a D

11階 催会場 〈即売〉 ■2月25日(火) → 3月3日(月):7日間 ※連日午後8時まで開催。ただし3月1日(土)は午後8時30分まで、最終日は午後6時閉場。 化粧室 55 温泉市場 お食事処 <生ばふんうにいくら丼> Edy ※イートインは各日10時30分オープン、 お休み処 ラストオーダーは閉場の30分前、 チャージ機 総合受付 最終日は午後5時ラストオーダー。 56 25 上和田有機米 《 1 実演 19 37 生産組合 43 小林金物 5 興洋フリーズ お 鳴海屋 菓秀苑 森長 <遠藤五一さんの 小豆島お肉の山下 <あごだしめんたい> こしひかり> 食 <藁焼きトロかつお <半熟生カステラ> <銀シャリ羽釜> 事 <くるくる煮豚> のタタキ> 処》 20 実演 24 38 エ A D モツホルモン奈良屋 G M 2 実演 角煮家こじま <煮込みホルモン 築 レ 4 秋津野直売所きてら 42 鶴太屋 <角煮まん> 久慈ファーム 地 前田海産 <南高梅ジュース 39 肉の小林 <煮込み ベ <鳥取のハワイ名物・ <辛子明太子> ー <山形牛さくらんぼ漬> ハンバーグ> 鳥 父ちゃんコロッケ> 23 21 新世 藤 あき津゛ <白菜きむち> 41 三谷牧場 分 40三陸海鮮料理 タ <金の ー 3 河久 <めんたいこ> 22 今村芳翠園本舗 中村家 <特製 ヨーグルト> 親子丼> <真ふぐからあげ> <一休ロール> <海宝漬> 6 実演 13 12 26 実演 30 48 ヤマキ醸造 おやきや 佃の佃煮 すし幸 みさきまぐろ倶楽 44 杉清 ・豆庵 総本家 <昆布〆 <とろまん> <能登がき> 刺身> 美味料理研究所 <豆乳レアチーズ> <さつまあげ> <門前おやき> 27 ぷりんやさん 57 11 土佐鮮活処 <奥沢ぷりん> B 吉雪 そのまんま E H N <小千谷ふるさとそば> <ばんのうわりした> 7 実演 45 47 虎ノ門市場 2927 川越開運堂 富士見堂 サンエイ 荒忠商店 おすすめコ-ナー 10 <干し芋> 28 阿部牛肉加工 <てこね寿司> <厚焼き煎餅> <ふぐの子糠漬> デリカテッセン <道産牛すじ煮込みカレー> ハンスホールベック DMセントラルキッチン にしきや すや亀 46 8 9 ひだ千利庵 富久屋 <牛たんカレー> <五穀みそおこげ> <赤かぶら長熟漬> <ローストビーフ> <フライッシュケーゼ <いちご大福> ニーハオ <羽根付き餃子> 加賀守岡屋 <焼きいなり> 純系名古屋コーチン工房 <名古屋コーチン薫製> 14 実演 18 31 36 49 54 温泉市場 ミルク工房 丸加水産 江戸一 吹田商店 オホーツク・ <紅鮭荒塩造り 切身> <ジャージーミルクピス> 市場めし 兆 KIZASHI <銀だら味噌漬> <いかあられ> <梅昆布> テロワールの店 大和蒲鉾 <兆弁当(海鮮弁当)> <大和 浜千鳥> C <蒸しかぼちゃ> 32 誉食品 F 50 鳥藤 I ハマスイ O 15 実演 <手羽先 <ふかうら真鯛の <するめ数の子松前漬 35 辛み焼き> ごまだれ丼の素> 肴や一蓮 蔵 17 53 枕崎市漁業協同組合 北海道海産 <かにじゅうまい> 51 近江屋牛肉店 <枕崎かつおユッケ> 東水フーズ スイート 33 <ボイル <上州麦豚の がんじゅう オーケストラ 函館カール・レイモ ずわいがに姿> やきぶた> <紅豚ロースの味噌漬> 16 ン <秋田県産 <ベーコン> <山わさび漬 クレープ工房 ぎばさ> <スイートポテト> たらこ> 52 イベント <ブラック&ホワイト 34 トンデンファーム 築地田中商店 ミルクレープ> <鹿児島県産 & <骨つきソーセージ> <銀だら粕漬> うなぎ蒲焼> 日替わり 即売会 ○2月25日(火)10時~ 【番組公開収録(桂米助&橋本志穂)】 J ○2月26日(水)10時~ 【船上ボイルズワイガニ即売会】 紳士服イージーメード ○2月28日(金)11時・14時 DOWN UP 【日本一の米農家 遠藤五一氏トーク 2着セール ショー】 DOWN UP K ○3月2日(日)11時・14時・16時 エ ス カ レ ー タ ー 【虎ノ門市場おすすめ マグロ即売会】 ○3月3日(月)10時~ UP DOWN 髙島屋特選 UP DOWN ひな人形&五月人形陳列即売会 L Tokyo Television Toranomon-Ichiba Program, Happy Meal Travelog at Shinjuku Takashimaya Feb.25 Thu → Mar.3 Mon.