Food Byways: the Sugar Road by Masami Ishii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In This Issue

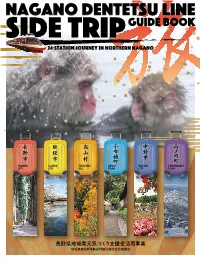

to Kanazawa In this issue to JoetsuJCT Toyoda-Iiyama I.C P.12 Nakano City Shinsyu-Nakano I.C P.14 Yudanaka Station Shinsyu-Nakano P.04 P.10 Station Nagano Yamanouchi Town Nagano City Obuse Town Snow Monkey Obuse Dentetsu Station Line Obuse P.A P.08 Suzaka Station Takayama Vill Nagano Zenkoji Temple Station P.06 Nagano I.C Expressway Suzaka City Nagano Expressway Joshinetsu Koshoku J.C.T Nagano Prefecture Nagano City Suzaka City Greetings from Northern 1Zenkoji × Soba× Oyaki p04 2 What´s Misosuki Don ? p06 Nagano! Come take a JoshinetsuExpressway Shinshu Matsumoto Airport Mathumoto I.C JR Hokuriku Shinkansen to Tokyo journey of 24 stations ! 02 Enjoy a scenic train ride through the 03 Nagano Hongo Kirihara Kamijyo Hino Kita-suzaka Entoku Nakano-Matsukawa Fuzokuchugakumae Murayama Shiyakushomae Shinano-Yoshida Suzaka Sakurasawa Shinsyu-Nakano Shinano-Takehara Gondo Obuse Zenkojishita Asahi Tsusumi Yomase Yudanaka Yanagihara Nagano countryside on the Nagano Dentetsu line. Nicknamed “Nagaden”, min 2 min 2 min 2 min 2 min 2 min 2 min 3 min 2 min 2 min 3 min 2 min 3 min 4 min 4 min 2 min 4 min 3 min 4 min 3 min 4 min 2 min 2 min 3 the train has linked Nagano City with Suzaka, Obuse, Nakano and Yamanouchi since it opened in 10- June, 1922. Local trains provide min 2 min 2 min 3 min 2 min 3 min 8 min 6 min 9 12min Limited B express leisurely service to all 24 stations min 2 14min min 6 min 9 12min along the way, while the express trains Limited A express such as the “Snow Monkey” reaches Takayama Village Obuse Town 【About express train 】 Yudanaka from Nagano Station in as quickly as 44 minutes. -

Table Grill Beverages

BULDAEGI BBQ HOUSE TABLE GRILL BEVERAGES Bottled Water — $2 Sparkling Water — $2.50 Hot Tea (Green or Earl Gray)— $1.75 Canned Soda — $1.75 Sweet /Unsweet Tea (No Refills) — $1.75 DOMESTIC BEER — $4 Yuengling Blue Moon IMPORTED BEER — $5 Tsingtao (China) Heineken (Holland) Asahi (Japan) Kirin Ichiban (Japan) Sapporo (Japan) OB (Korea) APPETIZERS Potato Pancake (감자전) — S / $10, L / $14 Crispy potato pancake. Kimchi Pancake (김치전) — S / $10, L / $14 Kimchi and vegetable pancake. Spicy. Haemul Pancake (해물파전) — $16 Crispy pancake with assorted seafood, carrot, green and white onion. House Japchae (불돼지잡채) — $14 Glass noodles, carrot, white and green onion. Choose a style: Pork, Beef, or Veggie. Duk Bok Ki* (떡볶기) — $14 Rice cake, fish cake, hard-boiled egg, hot pepper paste sauce. Spicy. Dak Gangjeong (닭강정) — $16 Crispy boneless fried chicken glazed with sweet, housemade sauce. Fried Dumplings (튀김만두) — $8 Deep-fried dumplings with chicken and vegetables. 8 pieces. Tang Su Yuk (탕수육) — $18 Deep-fried meat or tofu in housemade sweet & sour sauce. Choose a style: Beef, Pork, or Tofu. Spring Rolls - $8 Shredded cabbage, carrots, tofu, onions. 6 pieces. *Consuming raw or undercooked meats, poultry, seafood, shellfish, or egg may increase your risk of food-borne illnesses. TABLE GRILL Choose a minimum of 2 BBQ orders or 1 Combo. Includes lettuce wraps, banchan, corn cheese, steamed egg*. Extra small sides — $6 each. (See back for options) Pork Combo A — $50.50 Choose any 5 meats from Pork BBQ. Serves 2. Pork Combo B — $70.50 Choose any 7 meats from Pork BBQ. Serves 3-4. -

ON-YASAI Ice Cream Hiyashi Udon ON-YASAI's Chilled Udon Noodles Strawberry Cheese Tart ON-YASAI Aisu Ichigo No Chizu Taruto

Enjoy dishes with the added touch of delicious ingredients, perfect with alcoholic beverages. ON-YASAI Special Stir it all up, Snacks "Tsumire" (Meatball) Choice of Tsumire add it into the Hashi-Yasume ON-YASAI Tokusei Tsumire Okonomi Tsumire pot, and enjoy. Plum Pulp and Cartilage Dressing Dish Basil and Cheese Tsumire Pickled Plum and Perilla Spicy Cod Roe, Cheese, Bainiku to Nankotsu no Aemono Standard Tsumire on Brown Sugar and Bajiru Chizu Tsumire Leaf Rice Cake Tsumire and Rice Cake Tsumire Broad Beans Half-Cut Bamboo, Ume Shiso Mochi Tsumire Mentai Chizu Mochi Tsumire Hitokuchi Kokuto Soramame beloved for over 10 years 1 2 3 Seasoned Quail Eggs Uzura no Ajitama toHow make a "Tsumire" (meatball) Add the ingredients. Stir well. Add to the pot, and that's it. Kimchee Amakara Kimuchi Italian Herbs and Cheese Tomato Salad Tomato no Itarian Sarada Namuru-Style Meat Peanut Sprouts Namuru-fu Pinattsu Moyashi Colorful Pickled Vegetables Irodori Yasai no Pikurusu Fluy Bell Pepper Mousse Meats dier depending on the course. Funwari Papurika Musu Please see the separate “Tabehoudai Course Menu (All-You-Can-Eat Menu)” Recommended Recommended for the Meat Menu. Peanut Fluy Bell Sprouts Pepper Mousse A characteristic of peanuts is their sweetness and aroma, Enjoy the sweetness of vegetables and scent as well as their vitamin E, which helps with anti-aging; of basil with the widely enjoyed taste of bell protein, which is linked to beautiful skin; and dietary peppers in mousse. Recommended for ber, which helps to promote bowel movements. children who don't like vegetables. - Enjoy Shabu-Shabu More with ON-YASAI Curry - is curry makes the most of vegetables' sweetness, and is perfect with meat and udon noodles Top it o with meat Pour it on udon noodles Curry and Rice (Available in a half serving) Curry with Meat Curry with Udon To have great tasting Shabu-Shabu, one important thing is the e importance of thickness of the meat. -

Collection of Products Made Through Affrinnovation ‐ 6Th Industrialization of Agriculture,Forestry and Fisheries ‐

Collection of Products made through AFFrinnovation ‐ 6th Industrialization of Agriculture,Forestry and Fisheries ‐ January 2016 Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries In Japan, agricultural, forestry and fisheries workers have been making efforts to raise their income by processing and selling their products in an integrated manner to create added value. These efforts are called the “AFFrinnovation,” and agricultural, forestry and fisheries workers throughout the country have made the best use of inventiveness to produce a variety of products. This book introduces products that were created through the efforts to promote the AFFrinnovation. We hope this book would arouse your interest in the AFFrinnovation in Japan. Notes ○ Information contained in this book is current as of the editing in January 2016, and therefore not necessarily up to date. ○ This book provides information of products by favor of the business operators as their producers. If you desire to contact or visit any of business operators covered in this book, please be careful not to disturb their business activities. [Contact] Food Industrial Innovation Division Food Industry Affairs Bureau Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries URL:https://www.contact.maff.go.jp/maff/form/114e.html Table of Contents Hokkaido Name of Product Name Prefecture Page Business Operator Tomatoberry Juice Okamoto Nouen Co., Ltd. Hokkaido 1 Midi Tomato Juice Okamoto Nouen Co., Ltd. Hokkaido 2 Tokachi Marumaru Nama Cream Puff (fresh cream puff) Okamoto Nouen Co., Ltd. Hokkaido 3 (tomato, corn, and azuki bean flavors) Noka‐no Temae‐miso (Farm‐made fermented soybean Sawada Nojo LLC Hokkaido 4 paste) Asahikawa Arakawa Green Cheese Miruku‐fumi‐no‐ki (milky yellow) Hokkaido 5 Bokujo LLC Asahikawa Arakawa Farm Green Cheese Kokuno‐aka (rich red) Hokkaido 6 LLC Menu at a farm restaurant COWCOW Café Oono Farm Co., Ltd. -

Seven Weeks on the Henro Michi Steps Along the Shikoku Island 88 Temple Pilgrimage Marc Pearl

Seven Weeks on the Henro Michi Steps along the Shikoku Island 88 Temple Pilgrimage Marc Pearl The Settai Offering (Temples #7- #11) The Settai Offering is a fundamental aspect of the Henro Pilgrim experience. Offerings and services of all kinds are given to the Pilgrim as he makes his way along the island paths. Meals, snacks and cups of tea, items necessary to the Henro such as incense sticks and candles and coins, as well as places to spend the night, are donated by the kind people of Shikoku. Although the Henro is a stranger traveling but briefly through the neighborhood, he is greeted as a friend, and invited to sit on the veranda or inside the front genkan entrance, leaving the hot sun and dusty road for some moments to relax and share a few words. During my second day of walking, between Temples #7 and #8, I got caught in a gentle sunshower, so I stood under the eaves of a house alongside the road. From the open doorway of the genkan, a grandmother motioned me inside. We sat quietly and drank green tea and nibbled some crackers while we watched the rain and talked about the Pilgrimage. In Spring and Summer there are a lot of chartered buses whizzing by her door, she told me. In the fall, it was calmer. She doesn’t see very many walking pilgrims nowadays, not like the old days after the war when, for a lack of jobs or anything else to do, many people would do the Pilgrimage, before they had cars or those fancy taxis and buses. -

Download Our Menu In

Appetizer Specials King Crab Salad 17 Mixture of cooked King Crab Meat, Seaweed Salad, Cucumber, Mayo and Tobiko. Jalapeño Calamari 12 Fried Calamari Served with House Jalapeño Sauce. Crispy Crab Shumai 14 Crispy Fried Shumai Skin stuffed with Sweet Blue Crab Meat and Onion. Garnished with Tobiko and Sprouts, Served with Spicy Mayo. Lady in White 17 A 3 tiered roll consisting of thinly sliced White Tuna, Avocado, Tuna and Masago. Stuffed with Spicy Tuna, Lobster Salad, Avocado, and drizzled with Yuzu Dressing. Sushi Sandwich 17 4 Pieces of Club Sandwich Styled Sushi with Tuna, Salmon, Kani, Avocado, Cucumber, Lettuce, Masago & Pink Seaweed in the Center. Topped with Wasabi Mayo. King Crab Hot Roll 19 Alaskan King Crab, Avocado and Masago Wrapped in the Center Deep Fried Until the Rice is Perfectly Soft and Chewy. Served with Chef’s Spicy Mango Salsa Coconut Shrimp Roll 17 Coconut Battered Tempura Shrimp Wrapped in a Roll, Topped w/ Lobster Salad, Masago and Thinly Sliced Avocado. Sprinkled with Fine Coconut Flakes, and Drizzled with Wasabi Dressing. Angry White Tuna Roll 17 Spicy White Tuna, Asparagus, Avocado and Tempura Flakes lnside. Topped With Seared White Tuna, Jalapeño and Chef’s Ginger Eel Sauce. Sprinkled with Crunchy Kani. Salad House Salad 5.5 Tofu Salad 8 Asparagus Salad 8 Avocado Salad 8 Bean Sprout Salad 8 Seasoned, Blanched Soy Bean Sprouts Mixed with White Sesame Seeds Hiyashi Wakame Salad 6 Seaweed Salad Hijiki 6 Cooked Seaweed Sprinkled with White Sesame Seeds in Chef's Special Light Sauce, Served Cold Edamame 5 Blanched -

Fujian Soda / Lye Zongzi with Red Bean Paste

DILMAH RECIPES Fujian Soda / Lye Zongzi with Red Bean Paste 0 made it | 0 reviews Alkaline water (potassium carbonate and sodium bi- carbonate) turns the glutinous rice into an attractive warm yellow colour. This vegan zongzi is served plain with sugar, honey or syrup. It can also be filled with sweet paste (lotus or red bean). Sub Category Name Food Main Courses Savory Recipe Source Name Tea Inspired Festivities Festivities Name Chinese New Year Festival Dragon Boat / Duanwu Festival Glass Type Twelve Used Teas t-Series Green Tea 1 / 2 DILMAH RECIPES Ingredientswith Jasmine Flowers Fujian Soda / Lye Zongzi with Red Bean Paste 650g or 3 cups glutinous rice 2 tbsp lye/alkaline water 1,1/2 tbsp cooking oil 400g red bean paste 1 tbsp salt 28 dried bamboo leaves, soaked overnight Kitchen twine Methods and Directions Fujian Soda / Lye Zongzi with Red Bean Paste Soak the glutinous rice in five cups of water overnight. Drain thoroughly and then mix with cooking oil and lye. The rice should turn yellow. Set aside. Divide the bean paste into 12 portions of 30g. Blanch the bamboo leaves in boiling water until soft (about 10 minutes). To assemble the zongzi, form a cone using 2 bamboo leaves, placing one on top of another and fold into a cone. Place 1 tablespoon of rice into the cone. Make a small well, then place one portion of red bean paste in it. Cover with 1,1/2 tablespoons of rice. Pack all ingredients lightly, and smoothen the top with a clean wet spoon. Complete the wrapping and secure with kitchen twine. -

20180910 Matcha ENG.Pdf

Matcha served with wagashi Sencha served with wagashi Whole tea leaves ground into fine, ceremonial grade Choose from three excellent local teas curated by powder and whipped into a foamy broth using a our expert staff. Select one Kagoshima wagashi to method unchanged for over 400 years. Choose one accompany your tea for a refreshing break. Kagoshima wagashi to accompany your drink for the perfect pairing of bitter and sweet. ¥1,000 ¥850 Please choose your tea and wagashi from the following pages. All prices include tax. Please choose your sencha from the options below. Chiran-cha Tea from fields surrounding the samurai town of Chiran. Slightly sweet with a clean finish. Onejime-cha Onejime produces the earliest first flush tea in Kagoshima. Sharp, clean flavour followed by a gently lingering bitterness. Kirishima Organic Matcha The finest organically cultivated local matcha from the mountains of Kirishima. Full natural flavour with a slightly astringent edge. Oku Kirishima-cha Tea from the foothills of the Kirishima mountain range. Balanced flavour with refined umami and an astringent edge. Please choose your wagashi from the options below. Seasonal Namagashi(+¥200) Akumaki Sweets for the tea ceremony inspired by each season. Glutinous rice served with sweet toasted soybean Ideal with a refreshing cup of matcha. flour. This famous snack was taken into battle by tough Allergy information: contains yam Satsuma samurai. Allergy information: contains soy Karukan Hiryu-zu Local yams combined with refined rice flour and white Sweet bean paste, egg yolk, ginkgo nuts, and shiitake sugar to create a moist steamed cake. Created 160 mushrooms are combined in this baked treat that has years ago under the orders of Lord Shimadzu Nariakira. -

Read Book Wagashi and More: a Collection of Simple Japanese

WAGASHI AND MORE: A COLLECTION OF SIMPLE JAPANESE DESSERT RECIPES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Cooking Penguin | 72 pages | 07 Feb 2013 | Createspace | 9781482376364 | English | United States Wagashi and More: A Collection of Simple Japanese Dessert Recipes PDF Book Similar to mochi, it is made with glutinous rice flour or pounded glutinous rice. Tourists like to buy akafuku as a souvenir, but it should be enjoyed quickly, as it expires after only two days. I'm keeping this one a little under wraps for now but if you happen to come along on one of my tours it might be on the itinerary Next to the velvety base, it can also incorporate various additional ingredients such as sliced chestnuts or figs. For those of you who came on the inaugural Zenbu Ryori tour - shhhhhhhh! Well this was a first. This classic mochi variety combines chewy rice cakes made from glutinous rice and kinako —roasted soybean powder. More about Hishi mochi. The sweet and salty goma dango is often consumed in August as a summer delicacy at street fairs or in restaurants. The base of each mitsumame are see-through jelly cubes made with agar-agar, a thickening agent created out of seaweed. Usually the outside pancake-ish layer is plain with a traditional filling of sweet red beans. Forgot your password? The name of this treat consists of two words: bota , which is derived from botan , meaning tree peony , and mochi , meaning sticky, pounded rice. Dessert Kamome no tamago. Rakugan are traditional Japanese sweets prepared in many different colors and shapes reflecting seasonal, holiday, or regional themes. -

Ach Food Companies Inc. Athena Foods Atlantic Beverage Company

ACH FOOD COMPANIES INC. BOOTH # 184 Item # Description Unit MFG # Allowance QTY 31340 24/1 LB CORN STARCH (ARGO) Case 2001561 $0.50 40614 4/1 GL SYRUP CORN SYRUP RED NO HFCS (KARO) Case 2010736 $2.00 AJINOMOTO BOOTH # 186 Item # Description Unit MFG # Allowance QTY 70804 6/4 LB APTZR MOZZARELLA STICK BREADED (FRED'S) Case 205120 $0.50 71851 6/2 LB APTZR GOUDA SMK BACON BITE (FRED'S) Case 0142020 $0.50 71853 4/4 LB APTZR PICKLE SPEAR GRL&ONION (FRED'S) Case 2270120 $0.50 A1001 TOASTED ONION BATTERED GREEN BEAN Case 0275720 $0.50 A1002 6/2 LB PICKLE CHIP BATTERED Case 0274120 $0.50 A1003 CHEESE CURD BATTERED Case 0606420 $0.50 ATHENA FOODS BOOTH # 191 Item # Description Unit MFG # Allowance QTY 42570 4/8 LB DRSNG MEDITERRANEAN (SWT LORAIN) Case 12804NMD 42572 4/8 LB DRSNG GINGER SOY (SWT LORAIN) Case 12804NGSD 42574 4/8 LB DRSNG BALSAMIC VINIAGRETTE (SWT LORAIN) Case 12804NBSD 42576 4/8 LB DRSNG POPPYSEED (SWT LORAIN) Case 12804NPSD 42578 4/8 LB DRSNG CAESAR VEGAN (SWT LORAIN) Case 12804NVSD 42760 12/13 OZ DRSNG SHIELD'S RETAIL (SHIELDS) Case 1312NSD 73322 4/8 LB SAUCE CHEESE (SWT LORAIN) Case 12804NCS 73324 4/3 LB PESTO FROZEN (SWT LORAIN) Case 4804NSP 74340 18/12 ct QUICHE FRZ SPINACH ATHN (ATHENA FOO) Case 1218NSQ ATLANTIC BEVERAGE COMPANY BOOTH # 196 Item # Description Unit MFG # Allowance QTY 12001 6/#10 BEAN BLACK #10 (SUNFIELD) Case 700250 12018 6/#10 OLIVE BLACK SLICED SPANISH (ASSAGIO) Case 700890 13219 6/108 OZ PINEAPPLE TIDBIT #10 (SUNFIELD) Case 703076 33210 4/6 LB SEASONING LEMON PEPPER (ASSAGIO) Case 708200 40841 4/1 GL SAUCE HOT FRANK'S (FRENCHS) Case 05560 40844 4/1 GL SAUCE HOT BUFFALO WING FRANKS (FRENCHS) Case 74161 41509 1/2000 CT SWEETNER (SPLENDA) Case 822413 Tuesday, September 3, 2019 Page 1 of 18 41573 4/1 GL PEPPER PEPPERONCINI (CORCEL) Case 701280 42633 1/12 KG OLIVE KALAMATA X LARGE 201/23 (CORCEL) Pail 701120 BARILLA GROUP INC. -

Vegan Lunch Box : 150 Amazing, Animal-Free Lunches Kids and Grown-Ups Will Love! / Jennifer Mccann

1600940729 text_rev.qxd 4/21/08 8:53 AM Page i PRAISE FOR VEGAN LUNCH BOX “Jennifer McCann’s cookbook makes vegan cooking accessible and fun. It’s informative but not stuffy, detailed yet concise, and the recipes are creative without being difficult. There are so many delicious, well put to- gether options here, it’s not only perfect for kids but for anyone who ever eats lunch!” —Isa Chandra Moskowitz, author of VEGANOMICON “Being a vegan kid just got a lot easier! The menus in Vegan LunchLunch BoxBox make it easy to plan a balanced and nutritious lunch for your kids (or your- self!). The variety alone makes it worth having.” —Erin Pavlina, author of RAISING VEGAN CHILDREN IN A NON-VEGAN WORLD “Destined to become a classic, this is the book vegan parents have been waiting for. And who knew? A vegan mom started a blog describing the lunches she made for her son for one school year, and it won the 2006 Bloggie Award for “Best Food Blog” (NOT “best VEGETARIAN food blog,” but “Best Food Blog,” period!). It inspired, delighted, and motivated not only vegan parents, but omnivores bored with their own lackluster lunches. This book will continue delighting with recipes that are as innovative, kid- pleasing, and healthful as they are delicious.” —Bryanna Clark Grogan, author of NONNA’S ITALIAN KITCHEN 1600940729 text_rev.qxd 4/21/08 8:53 AM Page ii This page intentionally left blank 1600940729 text_rev.qxd 4/21/08 8:53 AM Page iii Vegan Lunch Box 1600940729 text_rev.qxd 4/21/08 8:53 AM Page iv This page intentionally left blank 1600940729 text_rev.qxd 4/21/08 8:53 AM Page v Vegan Lunch Box 150 Amazing, Animal-Free Lunches Kids and Grown-Ups Will Love! Jennifer McCann A Member of the Perseus Books Group 1600940729 text_rev.qxd 4/21/08 8:53 AM Page vi Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. -

ESORA: the Rise of the Culinary Bambinos | High Net Worth

15/01/2019 ESORA: The Rise of the Culinary Bambinos | High Net Worth Dining (https://www.hnworth.com/article-category/dining) ESORA: The Rise of the Culinary Bambinos By Sihan Lee https://www.hnworth.com/article/2018/12/06/esora-the-rise-of-the-culinary-bambinos/ 1/9 15/01/2019 ESORA: The Rise of the Culinary Bambinos | High Net Worth December 6, 2018 Recommended 2018 has been an epic year of change for the F&B scene in Singapore, Insights (https://www.hnworth.com/article- notwithstanding the sad category/insights) departure/closure of several renowned institutions in the industry. With several big names out of action, this creates room for the younger, more ambitious chefs and restauranteurs to strive and crack the glass ceilings of fine dining. And for many of these up-and-comers, beige is (https://www.hnworth.com/article/201 the new white; and wood is the new 10-biggest-risks-for-2018/) marble. The 10 Biggest Risks for 2018 (https://www.hnworth.com/article/201 10-biggest-risks-for-2018/) Style (https://www.hnworth.com/article- category/style) (http://www.hnworth.com/wp- content/uploads/2018/11/Esora-Art- 1.jpg) Contributing significantly to these efforts, is the newly opened ESORA (https://www.restaurant-esora.com/), (https://www.hnworth.com/article/201 an intimate 26-seater Kappo-style to-get-the-nike-react-element-87- establishment that has recently added x-undercover/) the T.Dining Best New Restaurant award to its impending accolades, just https://www.hnworth.com/article/2018/12/06/esora-the-rise-of-the-culinary-bambinos/ 2/9 15/01/2019 ESORA: The Rise of the Culinary Bambinos | High Net Worth 3 months of opening its doors.