Early Farming Communities 4.?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subsistence Strategies and Burial Rituals: Social Practices in the Late Deccan Chalcolithic

Subsistence Strategies and Burial Rituals: Social Practices in the Late Deccan Chalcolithic TERESA P. RACZEK IN THE SECOND MILLENNIUM B.C., THE RESIDENTS OF THE WESTERN DECCAN region of India practiced an agropastoral lifestyle and buried their infant children in ceramic urns below their house floors. With the coming of the first millennium B.C., the inhabitants of the site of Inamgaon altered their subsistence practices to incorporate more wild meat and fewer grains into their diet. Although daily practices in the form of food procurement changed, infant burial practices remained constant from the Early Jorwe (1400 B.c.-lOOO B.C.) to the Late Jorwe (1000 B.c.-700 B.C.) period. Examining interments together with subsistence strategies firmly situates ideational practices within the fabric of daily life. This paper will explore the relationship between change and continuity in burial and subsistence practices around 1000 B.C. at the previously excavated Cha1colithic site of Inamgaon in the western Deccan (Fig. 1). By considering the act of burial as a moment of social construction that both creates and reflects larger traditions, it is possible to understand how each individual interment affects chronological variability. That burial traditions at Inamgaon were continuously recreated in the face of a changing society suggests that meaningful and significant practices were actively upheld. Burial practices at Inamgaon were both structured and fluid enough to allow room for individual and group expression. The con temporaneous variability that occurs in the burial record at Inamgaon may reflect the marking of various aspects of personhood. Burial traditions and the ability and desire of the living to conforITl to them vary over time and it is important to consider the specific social context in which they occur. -

(Social Sciences) Ancient Indian History Culture

PUNYASHLOK AHILYADEVI HOLKAR SOLAPUR UNIVERSITY, SOLAPUR Faculty of Humanities (Social Sciences) Ancient Indian History Culture and Archaeology M.A. Part I Semester I & II w.e.f. June, 2020 1 Punyashlok Ahilyadevi Holkar Solapur University, Solapur School of Social Sciences Dept. of Ancient Indian History Culture and Archaeology M.A. Part-I CBCS Pattern (New)w.e.f. June 2020 Marks : 100 (70+30) SEMESTER -I AIHCA Hard Core HCT 1.1 History of Ancient India up to 650 A.D. HCT 1.2 Ancient Indian Iconography HCT 1.3 Prehistory of India Soft Core (Anyone) SCT 1.1 Introduction to Archaeology SCT 1.2 Ancient Indian Literature Practical/Field Work/Tutorial HCP 1.1 Practical/Field Work-I SCP 1.2 Practical/Field Work-II Tutorials (Library Work) Note: - 70Marks for theory paper & 30 Marks on Class room Seminars/ Study Tour/ Tutorials/ Field Work/ Project. 2 Punyashlok Ahilyadevi Holkar Solapur University, Solapur School of Social Sciences, Dept. of Ancient Indian History Culture and Archaeology M.A. Part-I, Semester-I CBCS Pattern (New)w.e.f. June 2020 Marks : 100 (70+30) HCT-1.1 History of Ancient India Up to 650 AD 70 Unit- 1: Sources and Historiography of Ancient India i)Geography ii)Historiography iii) Sources of Ancient Indian History Unit 2: Early of political institutions in ancient India i. Janapadas, Republic (Ganrajya) , Mahajanapadas in ancient India ii. Rise of Magadha Empire iii. Persian and Greek Invasions: Causes and Impacts Unit 3: Mauryan and Post-Mauryan India i. Chandragupta Maurya and Bindusara ii. Ashoka, his successors and decline of the Mauryas iii. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Note: Page numbers in italics refer to figures and tables. 16R dune site, 36, 43, 440 Adittanallur, 484 Adivasi peoples see tribal peoples Abhaipur, 498 Adiyaman dynasty, 317 Achaemenid Empire, 278, 279 Afghanistan Acharyya, S.K., 81 in “Aryan invasion” hypothesis, 205 Acheulean industry see also Paleolithic era in history of agriculture, 128, 346 in Bangladesh, 406, 408 in human dispersals, 64 dating of, 33, 35, 38, 63 in isotope analysis of Harappan earliest discovery of, 72 migrants, 196 handaxes, 63, 72, 414, 441 skeletal remains found near, 483 in the Hunsgi and Baichbal valleys, 441–443 as source of raw materials, 132, 134 lack of evidence in northeastern India for, 45 Africa major sites of, 42, 62–63 cultigens from, 179, 347, 362–363, 370 in Nepal, 414 COPYRIGHTEDhominoid MATERIAL migrations to and from, 23, 24 in Pakistan, 415 Horn of, 65 related hominin finds, 73, 81, 82 human migrations from, 51–52 scholarship on, 43, 441 museums in, 471 Adam, 302, 334, 498 Paleolithic tools in, 40, 43 Adamgarh, 90, 101 research on stature in, 103 Addanki, 498 subsistence economies in, 348, 353 Adi Badri, 498 Agara Orathur, 498 Adichchanallur, 317, 498 Agartala, 407 Adilabad, 455 Agni Purana, 320 A Companion to South Asia in the Past, First Edition. Edited by Gwen Robbins Schug and Subhash R. Walimbe. © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2016 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 0002649130.indd 534 2/17/2016 3:57:33 PM INDEX 535 Agra, 337 Ammapur, 414 agriculture see also millet; rice; sedentism; water Amreli district, 247, 325 management Amri, -

Unit 10 Chalcolithic and Early Iron Age-I

UNIT 10 CHALCOLITHIC AND EARLY IRON AGE-I Structure 10.0 Objectives 10.1 Introduction 10.2 Ochre Coloured Pottery Culture 10.3 The Problems of Copper Hoards 10.4 Black and Red Ware Culture 10.5 Painted Grey Ware Culture 10.6 Northern Black Polished Ware Culture 10.6.1 Structures 10.6.2 Pottery 10.6.3 Other Objects 10.6.4 Ornaments 10.6.5 Terracotta Figurines 10.6.6 Subsistence Economy and Trade 10.7 Chalcolithic Cultures of Western, Central and Eastern India 10.7.1 Pottery: Diagnostic Features 10.7.2 Economy 10.7.3 Houses and Habitations 10.7.4 Other 'characteristics 10.7.5 Religion/Belief Systems 10.7.6 Social Organization 10.8 Let Us Sum Up 10.9 Key Words 10.10 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 10.0 OBJECTIVES In Block 2, you have learnt about'the antecedent stages and various aspects of Harappan culture and society. You have also read about its geographical spread and the reasons for its decline and diffusion. In this unit we shall learn about the post-Harappan, Chalcolithic, and early Iron Age Cultures of northern, western, central and eastern India. After reading this unit you will be able to know about: a the geographical location and the adaptation of the people to local conditions, a the kind of houses they lived in, the varieties of food they grew and the kinds of tools and implements they used, a the varietie of potteries wed by them, a the kinds of religious beliefs they had, and a the change occurring during the early Iron age. -

The Decline of Harappan Civilization K.N.DIKSHIT

The Decline of Harappan Civilization K.N.DIKSHIT EBSTRACT As pointed out by N. G. Majumdar in 1934, a late phase of lndus civilization is illustrated by pottery discovered at the upper levels of Jhukar and Mohenjo-daro. However, it was the excavation at Rangpur which revealed in stratification a general decline in the prosperity of the Harappan culture. The cultural gamut of the nuclear region of the lndus-Sarasvati divide, when compared internally, revealed regional variations conforming to devolutionary tendencies especially in the peripheral region of north and western lndia. A large number of sites, now loosely termed as 'Late Harappan/Post-urban', have been discovered. These sites, which formed the disrupted terminal phases of the culture, lost their status as Harappan. They no doubt yielded distinctive Harappan pottery, antiquities and remnants of some architectural forms, but neither town planning nor any economic and cultural nucleus. The script also disappeared. ln this paper, an attempt is made with the survey of some of these excavated sites and other exploratory field-data noticed in the lndo-Pak subcontinent, to understand the complex issue.of Harappan decline and its legacy. CONTENTS l.INTRODUCTION 2. FIELD DATA A. Punjab i. Ropar ii. Bara iii. Dher Majra iv. Sanghol v. Katpalon vi. Nagar vii. Dadheri viii. Rohira B. Jammu and Kashmir i. Manda C. Haryana i. Mitathal ii. Daulatpur iii. Bhagwanpura iv. Mirzapur v. Karsola vi. Muhammad Nagar D. Delhi i. Bhorgarh 125 ANCiENT INDlA,NEW SERIES,NO.1 E.Western Uttar Pradesh i.Hulas il.Alamgirpur ili.Bargaon iv.Mandi v Arnbkheri v:.Bahadarabad F.Guiarat i.Rangpur †|.Desalpur ili.Dhola宙 ra iv Kanmer v.」 uni Kuran vi.Ratanpura G.Maharashtra i.Daimabad 3.EV:DENCE OF RICE 4.BURIAL PRACTiCES 5.DiSCUSS10N 6.CLASSiFiCAT10N AND CHRONOLOGY 7.DATA FROM PAKISTAN 8.BACTRIA―MARGIANAARCHAEOLOGICAL COMPLEX AND LATE HARAPPANS 9.THE LEGACY 10.CONCLUS10N ・ I. -

Unit 3 Harappan Civilisation and Other Chalcolithic Cultures

Introductory UNIT 3 HARAPPAN CIVILISATION AND OTHER CHALCOLITHIC CULTURES Structure 3.0 Introduction 3.1 The Background 3.2 The Harappan Culture 3.3 Urbanism 3.4 State Structure 3.5 Social Structure 3.6 End of the Harappan Civilization 3.7 Other Chalcolithic Cultures 3.8 Summary 3.9 Glossary 3.10 Exercises 3.11 Suggested Readings 3.0 INTRODUCTION The purpose of this Unit is to investigate more complex social structures than those covered in the previous Unit. This complexity arises due to the emergence of the state in the 3rd millennium BC. This early state is an inchoate one, incorporating many elements of tribal societies. This Bronze Age state is also quite different from the states of later periods, in no small measure due to the lack of commoditisation and coined money in this period. That this period also witnessed the first experiments in urbanism in the subcontinent adds to its complexity. These developments were basically confined to the North-western parts of the subcontinent and one must be aware that other socio-political structures, like band, tribal or chiefship level societies, may have existed contemporaneously in this and other areas. So far, we have seen incipient stages of social development, encompassing the band and tribal levels. In this Unit, we will discuss the other two stages of development, namely chiefdom (or chiefship) and state. Structurally, the chiefdom resembles the tribal level with the beginnings of social stratification, a political office and redistributive economy. On the other hand, there is a marked difference between tribal or chiefdom and state societies. -

Chalcolithic Cultures of India

4/1/2020 .The discovery of the Chalcolithic culture at Jorwe in 1950 opened a new phase in the prehistory of the Deccan. Chalcolithic Cultures of India .Since then a large number of Chalcolithic habitation sites have been discovered as a result of systematic exploration not only in the Deccan but also in other parts of the country bringing to light several regional Hkkjr dh rkezik’kkf.kd laLd`fr;k¡ cultures. .Large scale excavations have been conducted at Ahar and Navadatoli, both are Chalcolithic sites. .Most of these cultures are post Harappa, a few like Kayatha are contemporaneous Harappa. .An important feature is their painted pottery, usually black-on-red. Dr. Anil Kumar .The people subsisted on farming, stock-raising, hunting and fishing. .They used copper on restricted scale as the metal was scarce. Professor .They were all rural culture. Ancient Indian History and Archaeology .It is enigmatic that most of these settlements were deserted by the end University of Lucknow 2nd millennium B.C. [email protected] .The Chalcolithic cultures such as Ahar, Kayatha, Malwa, and Jorwe are [email protected] discussed further. Kayatha Culture Out of over 40 sites of Kayatha Culture, two of them namely Kayatha and Dangwada have been excavated. This Chalcolithic culture was named after the type site Kayatha, in Ujjain dist., Madhya Pradesh. The excavation was due to the joint collaboration of Deccan College, Pune and Department of Ancient Indian History, Culture and Archaeology, Vikram University, Ujjain. They lived in small huts having well-rammed floors. The main ceramics of Kayatha- Chocolate-slipped, incised, sturdy and well baked Kayatha ware. -

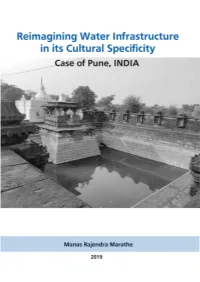

Reimagining Water Infrastructure in Its Cultural Specificity

Reimagining Water Infrastructure in its Cultural Specificity Case of Pune, INDIA. Manas Rajendra Marathe Supervisors Prof. Dr-Ing. Annette Rudolph-Cleff Prof. Dr Gerrit Jasper Schenk Fachgebiet Entwerfen und Stadtwicklung Fachbereich Architektur 2019 REIMAGINING WATER INFRASTRUCTURE IN ITS CULTURAL SPECIFICITY Case of Pune, INDIA. Genehmigte Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Ingenieurwissenschaften (Dr-Ing.) von M.Sc. Manas Rajendra Marathe aus Pune, Indien. Graduiertenkolleg KRITIS 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr-Ing. Annette Rudolph-Cleff 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr Gerrit Jasper Schenk Tag der Einreichung: 11-09-2019 Tag der Prüfung: 21.10.2019 Fachgebiet Entwerfen und Stadtwicklung Fachbereich Architektur (FB 15) Technische Universität Darmstadt L3 01 El- Lissitzky Straße 1 64287 Darmstadt URN: urn:nbn:de:tuda-tuprints-92810 URI: https://tuprints.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/id/eprint/9281 Published under CC BY 4.0 International https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Darmstadt, October 2019. Cover page: Photo of Barav at Loni Bhapkar, Pune. Erklärung zur Dissertation Hiermit versichere ich, die vorliegende Dissertation ohne Hilfe Dritter nur mit den angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmitteln angefertigt zu haben. Alle Stellen, die aus Quellen entnommen wurden, sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. Diese Arbeit hat in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form noch keiner Prüfungsbehörde vorgelegen. Darmstadt, den 11-09-2019. ________________________ (Manas Rajendra Marathe) Acknowledgements The culmination of this dissertation would not have been possible without the help and support of many people and institutions. Firstly, I express my sincere gratitude towards my Supervisor Prof. Dr-Ing. Annette Rudolph Cleff and my Co-Supervisor Prof. Dr Gerrit Jasper Schenk for their constant encouragement, guidance and wholehearted support. -

![[Ancient History] Syllabus](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5432/ancient-history-syllabus-4155432.webp)

[Ancient History] Syllabus

NEHRU GRAM BHARTI VISHWAVIDYALAYA Kotwa-Jamunipur-Dubawal ALLAHABAD SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE CLASSES (I & II, III & IV Semester) (Revised 2016) DEPARTMENT OF ANCIENT HISTORY, CULTURE & ARCHAEOLOGY (1) COURSE STRUCTURE First –Semester Pap. Content Unit Lec. Credit Mar. No. Paper –I Aspects of Ancient Indian Culture 05 40 04 100 (Political Social an Economic (80+20) Institutions) Paper –II Political History of Ancient India 05 40 04 100 (From : 6th Century B.C. to C. 185 B.C) (80+20) Paper -III Indian Paleography 05 40 04 100 (80+20) Paper-IV Paper IV (a) : Archaeological Theories 05 40 04 100 (Archaeology Group) (80+20) OR Paper IV B : Elements of Indian Archaeology Prehistory (Non-Archaeology Group) Semester -II Paper -I Aspects of Ancient Indian Culture 05 40 04 100 (Political Social an Economic Institutions) (80+20) Paper-II Political History of Ancient Indiaa (From C 05 40 04 100 185 B.C. to 319 A.D.) (80+20) Paper –III Indian Numismatics 05 40 04 100 (80+20) Paper-IV(a) Archaeological Methods and Techniques 05 40 04 100 (Archaeology Group) (80+20) OR Elements of Indian Archaeology Protohistory and Historical Archaeology (Non-Archaeology Group) Viva – voice a All Groups 01 100 marks Total Marks First & II Semester Total Marks 900 (2) COURSE STRUCTURE Third –Semester Pap. Content Unit Lec. Credit Mar. No. Paper –I Political History of Ancient India (From 05 40 04 100 AD 319 to 550 A.D.) (80+20) Paper –II Historiography and theories of History 05 40 04 100 (80+20) Paper –III (a) Pre-History : Paleolithic Cultures (With 05 40 04 100 -

Crafts and Technologies of the Chalcolithic People of South Asia: an Overview

Indian Journal of History of Science, 50.1 (2015) 42-54 DOI: 10.16943/ijhs/2015/v50i1/48111 Crafts and Technologies of the Chalcolithic People of South Asia: An Overview Vasant Shinde and Shweta Sinha Deshpande* (Received 15 January 2015) Abstract The Chalcolithic or the Early Farming community flourished from 7000 BC to first millennium BC all over South Asia due to many factors, including climate change and population pressure. A large number of sites discovered and selected ones excavated have thrown flood of light on various aspects of their lifestyle, including crafts and technological advances made by these people. Most of the technologies were innovated due to sheer necessities. This paper discusses the evidence from excavated sites a variety of pyro and non-pyro technologies the Chalcolithic people introduced and used over such a long period. Key words: Ahar culture, Chalcolithic, Chalcolithic technology, Deccan, Jorwe culture, Kayatha culture, Northwest India, South Asia. 1. INTRODUCTION steady growth and gradual induction of complex Technology forms the most important technologies from time to time. The rate of aspect of any culture, as it is the gauge for technological change that took place until the assessing economic and social developments introduction of farming (the period of the Early within human society during its various phases of Farming communities is usually referred to as history. It is the systematic study of techniques either Neolithic in some regions or Chalcolithic (craft) for making and doing things; and is in other) was slow and spread over a long period concerned with the fabrication and use of artefacts. -

History of the World Research

History of the World Research History of Civilisation Research Notes 200000 - 5500 BCE 5499 - 1000 BCE 999 - 500 BCE 499 - 1 BCE 1 CE - 500 CE 501 CE - 750 CE 751 CE - 1000 1001 - 1250 1251 - 1500 1501 - 1600 1601 - 1700 1701 - 1800 1801 - 1900 1901 - Present References Notes -Prakrit -> Sanskrit (1500-1350 BCE) -6th Dynasty of Egypt -Correct location of Jomon Japan -Correct Japan and New Zealand -Correct location of Donghu -Remove “Armenian” label -Add D’mt -Remove “Canaanite” label -Change Gojoseon -Etruscan conquest of Corsica -322: Southern Greece to Macedonia -Remove “Gujarati” label (to 640) -Genoa to Lombards 651 (not 750) Add “Georgian” label from 1008-1021 -Rasulids should appear in 1228 (not 1245) -Provence to France 1481 (not 1513) -Yedisan to Ottomans in 1527 (not 1580) -Cyprus to Ottoman Empire in 1571 (not 1627) -Inner Norway to sweden in 1648 (not 1721) -N. Russia annexed 1716, Peninsula annexed in 1732, E. Russia annexed 1750 (not 1753) -Scania to Sweden in 1658 (not 1759) -Newfoundland appears in 1841 (not 1870) -Sierra Leone -Kenya -Sao Tome and Principe gain independence in 1975 (not 2016) -Correct Red Turban Rebellion --------- Ab = Abhiras Aby = Abyssinia Agh = Aghlabids Al = Caucasian Albania Ala = Alemania Andh = Andhrabhrtya Arz = Arzawa Arm = Armenia Ash = Ashanti Ask = Assaka Assy/As = Assyria At = Atropatene Aus = Austria Av = Avanti Ayu = Ayutthaya Az = Azerbaijan Bab = Babylon Bami = Bamiyan BCA = British Central Africa Protectorate Bn = Bana BNW = Barotseland Northwest Rhodesia Bo = Bohemia BP = Bechuanaland -

Department of Ancient History, Culture and Archaeology University Of

Department of Ancient History, Culture and Archaeology University of Allahabad, Prayagraj-211 002 Syllabus modified only for Covid-19 period due to unprecedented situation B.A. Part-1 Paper-I: Early Cultures and Civilizations of India Unit-I : Definition of Archaeology and relation with other disciplines; Palaeolithic Cultures: Salient features with special reference to Belan Valley & Son Valley. Unit-II : Mesolithic Cultures: Salient features with special reference to Vindhyas, Ganga Plains. Neolithic Cultures: Salient features with special reference to North-West India, South India & Vindhyas. Unit-III : Harappan Civilization: Origin, Salient features, decline. Unit-IV : Chalcolithic Cultures – Kayatha Culture, Ahar Culture, Malwa Culture, Jorwe Culture & Copper hoards. UNIT-V : (a) Iron Age: Antiquity of Iron. (b) Sites: Bhaghwanpura, Atranjikhera, Hastinapur & Kausambi. Department of Ancient History, Culture and Archaeology University of Allahabad, Prayagraj-211 002 Syllabus modified only for Covid-19 period due to unprecedented situation B.A. Part-1 Paper-II: History of India upto the Kushanas (C.600 B.C. – C. 319 A.D.) Unit-I : Sources : Literary -Indian and Foreign Archaeological Unit-II : Early State Formation: The Mahajanapadas ; Rise of Magadha from Bimbisara to Mahapadma Nanda. Alexander’s Invasion, Monarchical States; Nature of Republics. Unit-III : Mauryan Empire and its Decline: Magadhan Expansion in the time of Chandragupta Maurya – administration Ashoka and his Dhamma Decline of the Mauryan Empire. Unit-IV : Political Fragmentation (C. 200 BC – AD 300): Early History of Satavahanas, Achievements of Pushyamitra Shunga and Gautamiputra Satkarni. Shaka-Satavahana Struggle. UNIT-V : Foreign Invasions and Dynasties - Shakas & Kushanas : Kanishka–I : Date and Achievements Department of Ancient History, Culture and Archaeology University of Allahabad, Prayagraj-211 002 Syllabus modified only for Covid-19 period due to unprecedented situation B.A.