Reimagining Water Infrastructure in Its Cultural Specificity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ashtavinayaka Temples, the Yatra Vidhi and More

Newsletter Archives www.dollsofindia.com Ashtavinayaka - the Eight Holy Abodes of Ganesha Copyright © 2018, DollsofIndia Sri Ganesha, also known as Vinayaka, is one of the most popular deities of the Hindu pantheon. Highly revered as the Harbinger of Success and the Remover of Obstacles, this Elephant- Headed son of Shiva and Parvati is venerated not only by Hindus, but also by people from all religions and all walks of life; from all over the world. One can find innumerable Ganesha temples all over the globe. In fact, all Hindu temples; irrespective of who the main deity is; necessarily have at least one shrine dedicated to Vighnavinayaka. Devotees first visit this shrine, pray to Ganesha to absolve them of their sins and only then proceed to the main sanctum. So exalted is the position of this God in Hindu culture. Shola Pith Ganapati Sculpture There are eight forms of Vinayaka, collectively referred to as Ashtavinayaka ('Ashta' in Sanskrit means 'eight'). The Ashtavinayaka Yatra implies a pilgrimage to the eight Vinayaka temples, which can be found in the Indian State of Maharashtra, situated in and around the city of Pune. The Yatra follows a particular route, in a pre-ascertained sequence. Each of these ancient Ashtavinayaka temples features a distinct murti (idol) of Ganesha and has a different legend behind its existence. Not only that; the appearance of each murti; even the angle of his trunk; are all distinct from one another. In this post, we bring you all the details on the Ashtavinayaka temples, the Yatra vidhi and more. Resin Ashtavinayak with Shloka on Wood - Wall Hanging The Ashtavinayaka Temples The eight temples of Ashtavinayaka, in their order, are as follows: 1. -

Sr. No. College Name University Name Taluka District JD Region

Non-Aided College List Sr. College Name University Name Taluka District JD Region Correspondence College No. Address Type 1 Shri. KGM Newaskar Sarvajanik Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Pandit neheru Hindi Non-Aided Trust's K.G. College of Arts & Pune University, ar ar vidalaya campus,Near Commerece, Ahmednagar Pune LIC office,Kings Road Ahmednagrcampus,Near LIC office,Kings 2 Masumiya College of Education Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune wable Non-Aided Pune University, ar ar colony,Mukundnagar,Ah Pune mednagar.414001 3 Janata Arts & Science Collge Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune A/P:- Ruichhattishi ,Tal:- Non-Aided Pune University, ar ar Nagar, Dist;- Pune Ahmednagarpin;-414002 4 Gramin Vikas Shikshan Sanstha,Sant Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune At Post Akolner Tal Non-Aided Dasganu Arts, Commerce and Science Pune University, ar ar Nagar Dist Ahmednagar College,Akolenagar, Ahmednagar Pune 414005 5 Dr.N.J.Paulbudhe Arts, Commerce & Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune shaneshwar nagarvasant Non-Aided Science Women`s College, Pune University, ar ar tekadi savedi Ahmednagar Pune 6 Xavier Institute of Natural Resource Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Behind Market Yard, Non-Aided Management, Ahmednagar Pune University, ar ar Social Centre, Pune Ahmednagar. 7 Shivajirao Kardile Arts, Commerce & Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Jambjamb Non-Aided Science College, Jamb Kaudagav, Pune University, ar ar Ahmednagar-414002 Pune 8 A.J.M.V.P.S., Institute Of Hotel Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag -

Magarpatta-Nova-8502.Pdf

APARTMENTS 2 & 2.5 BHK www.novaproject.in WELCOME TO THE BRIGHT SIDE OF LIFE. Strategically located in Mundhwa, close to every possible convenience that one can ask for, presenting Nova – 2 & 2.5 BHK apartments. An ode to new-age professionals, these homes are planned keeping the requirements of modern, urban family in mind. Aesthetically designed with state-of- the-art specifications, Nova boasts of an elegant living room, with a plush kitchen cum dining area and spacious bedrooms to suit your stature. With a good inlay for sunlight and proper ventilation, these apartments promise to take you to the bright side of life. Welcome aboard. SPECIFICATIONS: • Structure: Reinforced Cement Concrete (RCC) structure • Flooring: Vitrified tiles • External walls: Reinforced Cement Concrete (RCC) shear walls • Kitchen Platform: Granite top platform with stainless steel sink and glazed • Internal walls: Autoclaved Aerated Cement (AAC) blocks and Reinforced tile dado up to ceiling. Provision for exhaust fan and water purifier. Cement Concrete (RCC) • Toilet: Flooring – Matt finish tiles • Internal Finishing: Gypsum finish for ceilings and walls Dado: Glazed tiles. Dado up to door top. • Door Frame and Shutters: • Plumbing: Concealed plumbing Apartment main doors and bedroom doors: Laminated door frames with • Sanitary ware: Standard sanitary ware with Brass Chromium plated fittings laminated door shutters and good quality door fittings • Painting: External – Acrylic / Texture paint Apartment toilet door: Granite door frames with laminated door shutter Internal: Oil bound distemper and good quality door fittings Grills: Enamel paint Apartment Balcony Door: Powder coated Aluminium sliding door • Lifts: Lift with diesel generator backup • Windows: Powder coated Aluminium sliding windows with M.S. -

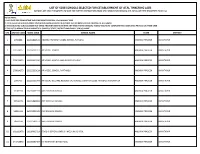

List of 6038 Schools Selected for Establishment of Atal Tinkering

LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. LAST DATE FOR COMPLETING THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS : 31st JANUARY 2020 2. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST OPEN A NEW BANK ACCOUNT IN A PUBLIC SECTOR BANK FOR THE PURPOSE OF ATL GRANT. 3. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST NOT SHARE THEIR INFORMATION WITH ANY THIRD PARTY/ VENDOR/ AGENT/ AND MUST COMPLETE THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS ON THEIR OWN. 4. THIS LIST IS ARRANGED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER OF STATE, DISTRICT AND FINALLY SCHOOL NAME. S.N. ATL UID CODE UDISE CODE SCHOOL NAME STATE DISTRICT 1 2760806 28222800515 ANDHRA PRADESH MODEL SCHOOL PUTLURU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 2 132314217 28224201013 AP MODEL SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 3 574614473 28223600320 AP MODEL SCHOOL AND JUNIOR COLLEGE ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 4 278814373 28223200124 AP MODEL SCHOOL RAPTHADU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 5 2995459 28222500704 AP SOCIAL WELFARE RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL JUNIOR COLLEGE FOR GIRLS KURUGUNTA ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 6 13701194 28220601919 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 7 15712075 28221890982 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 8 56051196 28222301035 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 9 385c1160 28221591153 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 10 102112978 28220902023 GOOD SHEPHERD ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 11 243715046 28220590484 K C NARAYANA E M SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Shiva's Waterfront Temples

Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Subhashini Kaligotla All rights reserved ABSTRACT Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla This dissertation examines Deccan India’s earliest surviving stone constructions, which were founded during the 6th through the 8th centuries and are known for their unparalleled formal eclecticism. Whereas past scholarship explains their heterogeneous formal character as an organic outcome of the Deccan’s “borderland” location between north India and south India, my study challenges the very conceptualization of the Deccan temple within a binary taxonomy that recognizes only northern and southern temple types. Rejecting the passivity implied by the borderland metaphor, I emphasize the role of human agents—particularly architects and makers—in establishing a dialectic between the north Indian and the south Indian architectural systems in the Deccan’s built worlds and built spaces. Secondly, by adopting the Deccan temple cluster as an analytical category in its own right, the present work contributes to the still developing field of landscape studies of the premodern Deccan. I read traditional art-historical evidence—the built environment, sculpture, and stone and copperplate inscriptions—alongside discursive treatments of landscape cultures and phenomenological and experiential perspectives. As a result, I am able to present hitherto unexamined aspects of the cluster’s spatial arrangement: the interrelationships between structures and the ways those relationships influence ritual and processional movements, as well as the symbolic, locative, and organizing role played by water bodies. -

Pune District Geographical Area

73°20'0"E 73°30'0"E 73°40'0"E 73°50'0"E 74°0'0"E 74°10'0"E 74°20'0"E 74°30'0"E 74°40'0"E 74°50'0"E 75°0'0"E 75°10'0"E PUNE DISTRICT GEOGRAPHICAL AREA To war a ds K ad (MAHARASHTRA) aly nw an- ha Dom m bi ra vali B P ds imp r a a l ¤£N g w H a o -2 T 19°20'0"N E o KEY MAP 2 2 n N Jo m 19°20'0"N g a A e D CA-01 TH THANE DINGORE 46 H CA-02 # S ta OTUR o Ma # B n JUNNAR s CA-03 ik AHMADNAGAR /" rd Doh D a ± CA-04 am w PUNE GEOGRAPHICAL o AREA (MNGL) TO BE CA-10 EXCLUDED FROM PUNE T DISTRICT GEOGRAPHICAL AREA UMBRAJ 0 # -5 CA-01 H N£ CA-05 DHALEWADI TARF HAVELI ¤ CA-09 CA-11 # Y ed ALE gaon Re T servoir Lake # ow 2 CA-06 22 a CA-08 H- r 19°10'0"N d RAJURI N s RAIGARH # £¤ T 19°10'0"N ak CA-07 CA-12 #NARAYANGAON #BORI BK. li D ho CA-13 ke Dim WARULWADI BELHE sh SOLAPUR bhe # w SATARA Da # S a m H r 5 1 KALAMB Total Population within the Geographical Area as per Census 2011 # T ow 46.29 Lacs (Approx.) GHODEGAON ar Total Geographical Area (Sq KMs) No. of Charge Areas ds S /" CA-02 H 1 Sh 14590 13 12 MANCHAR (CT) iru WADA r # .! Charge Area Identification Taluka Name C CA-01 Junnar 19°0'0"N ha CA-02 Ambegaon sk 19°0'0"N am an D CA-03 Khed a m CA-04 Mawal CA-05 Mulshi S PETH H 5 # CA-06 Velhe 4 i G d CA-07 Bhor h a T od Na o d w CA-08 Purandhar i( e w R CA-03 i n KADUS v CA-09 Haveli a e K a # r u r v ) k CA-10 Shirur d a d A s i G R CA-11 Daund N RAJGURUNAGAR i s H v e d a CA-12 Baramati /" r r v a M i w CA-13 Indapur M Wa o d i A v T u H 54 a le Dam S 62 18°50'0"N m SH D N SHIRUR 18°50'0"N b £H-5 ¤0 N a /" i CA-04 #DAVADI AG #KENDUR LEGEND KHADKALE -

Service Provider of Ashtavinayak Darshan, Maharashtra

+91-8377808574 Choudhary Yatra Company Private Limited www.choudharyyatra.in We are one of the well known names of the industry that provides International and Domestic Tour & Travel services. Our services are widely applauded for their reliability, comfort and timely execution. A Member of P r o f i l e Established in the year 1994, we, Choudhary Yatra Company Private Limited, are one of the distinguished service providers of International and Domestic Tour & Travel. The proposed tour packages comprise of Ashtavinayak Darshan, Maharashtra & Goa Tours and Dwarka Rajasthan Tours. Because of impressive work in this field, we have achieved National Award from Tourism Ministry and National Tourism Award . We are well known in the market for providing unforgettable experience through our packages and lay huge emphasis on the safety, comfort and fulfillment of the varied needs of our valued clients. Owing to our reliable and flexible services, we have earned a large number of customers across the nation. To manage and execute the services with utmost perfection, we have recruited experienced and knowledgeable professionals. We are concerned with the comfort and safety of our travelers and carry out our plans keeping in mind the constraints of time and budget. Our customers place immense trust in our capabilities and rely on us for offering organized tours with optimum comfort and personalized attention. We have earned a large number of clients in the past as a result of our unmatched quality of service and an impressive & friendly treatment. We are a Private Limited Company under the capable leadership of Mr. Ravindra Barde. -

Brahma Suncity

https://www.propertywala.com/brahma-suncity-pune Brahma Suncity - Wadgaon Sheri, Pune Residential Apartments Brahma Suncity is located within the city's central districts, Wadgaon Sheri is possibly Pune's best kept real estate secret with a, comparatively, low price that offers tremendous potential for the appreciation in the near future. Project ID : J791190745 Builder: brahma builders Properties: Apartments / Flats, Residential Plots / Lands Location: Brahma Suncity, Wadgaon Sheri, Pune - 411014 (Maharashtra) Completion Date: Aug, 2011 Status: Started Description Gemini Developers is an endeavour of a group of professionals who have come together with their vast experience and knowledge of large infrastructural projects. We at Gemini Developers aim to undertake large infrastructure and turnkey projects using the latest equipment and technology available in India and managed by the best in the industry. Gemini Developers is a company of Engineers, Architects, Builders and planners. Gemini Developers provides high quality services to meet the needs of clients and customers. Brahma Suncity is located within the city's central districts, Wadgaon Sheri is possibly Pune's best kept real estate secret with a, comparatively, low price that offers tremendous potential for the appreciation in the near future.It is a 3BHK residential multistorey apartment, is available for the offer of rent , located in the heart of Pune. The property is in the vicinity of prime locations, therefore has an ease of access to important landmarks. The property has -

Kyra Brochure 14X10 for Print Copy

Site Address: S. No. 134/2/1, 2/2A, 2B/2, 3A, 3B & 4, Magarpatta, Pune. Call: +91 2-2615106, 30250700 | E-mail: [email protected] | www.marvelrealtors.com CONFIDENTIALLY LUXURIOUS 301-302, Jewel Tower, Lane 5, North Main Road, Koregaon Park, Pune - 411001. Architects Structural Design Architect of Records Landscape Architects Legal Advisor KYRA HB Design International Inc., Singapore. Design Werkz Engineering Pvt. Ltd., Pune. Rahul Malwadkar, Pune. Siteectonix Pvt. Ltd., Singapore Rajiv Patel & Associates, Pune. Magarpatta Road, Pune Confidentially Luxurious A Secret Destination Behind Closed Doors Well- Appointed Details Private Moments CONTENTS Quiet Landscapes Intuitive Technology Nature’s Sanctity Our Other Properties CONFIDENTIALLY LUXURIOUS There’s a brand of luxury that’s exclusive to you. One that you don’t talk about. One that’s best experienced surreptitiously. One that lets you please your innermost sensibilities with the very best of the very best. A life of luxury to you is one where pampering yourself is something you want to do in a space that let’s you let down your guard. Welcome to the confidentially luxurious life at Marvel Kyra. Discover a residence made for your discreet extravagances. A higher order of luxury that goes beyond labels and overt exhibition. Feel like you’re the only person in the world as you set foot inside your grand private lobby. Disappear into your state of the art apartment or duplex. Slip into as much or as Welcome to an indulgent life. little as you take a dip in your private plunge pool or lounge on your own sundeck. -

Industry Indcd Industry Type Commissio Ning Year Category

Investme Water_Co Industry_ Commissio nt(In nsumptio Industry IndCd Type ning_Year Category Region Plot No. Taluka Village Address District Lacs) n(In CMD) APAR Industries Ltd. Dharamsi (Special nh Desai Oil SRO Marg Refinary Mumbai Mahul Mumbai 1 Div.) 9000 01.Dez.69 Red III Trombay city 1899 406 Pirojshah nagar E.E. Godrej SRO Highway Industries Mumbai Vikhroli Mumbai 2 Ltd. 114000 06.Nov.63 Red III (E) city 0 1350 Deonar SRO Abattoir Mumbai S.No. 97 Mumbai 3 (MCGM) 214000 Red III Govandi city 450 1474.5 Love Groove W.W.T.F Municipal Complex Corporati ,Dr Annie on of Beasant BrihannM SRO Road Mumbai 4 umbai 277000 04.Jän.38 Red Mumbai I Worli city 100 3000 Associate d Films Industries SRO 68,Tardeo Mumbai 5 Pvt. Ltd. 278000 Red Mumbai I Road city 680 100 CTS No. 2/53,354, Indian 355&2/11 Hume 6 Antop Pipe SRO Hill, Mumbai 6 Comp. Ltd 292000 01.Jän.11 Red Mumbai I Wadala(E) city 19000 212 Phase- III,Wadala Truck Terminal, Ultratech Near I- Cement SRO Max Mumbai 7 Ltd 302000 01.Jän.07 Orange Mumbai I Theaters city 310 100 R68 Railway Locomoti ve Western workshop Railway,N s / .M. Joshi Carriage Integrate Marg Repair d Road SRO N.M. Joshi Lower Mumbai 8 Workshop 324000 transport 26.Dez.23 Red Mumbai I Mumbai Marg Parel city 3750 838 A G Khan Worly SRO Road, Mumbai 9 Dairy 353000 04.Jän.60 Red Mumbai I Worly city 8.71 2700 Gala No.103, 1st Floor, Ashirward Est. -

Subsistence Strategies and Burial Rituals: Social Practices in the Late Deccan Chalcolithic

Subsistence Strategies and Burial Rituals: Social Practices in the Late Deccan Chalcolithic TERESA P. RACZEK IN THE SECOND MILLENNIUM B.C., THE RESIDENTS OF THE WESTERN DECCAN region of India practiced an agropastoral lifestyle and buried their infant children in ceramic urns below their house floors. With the coming of the first millennium B.C., the inhabitants of the site of Inamgaon altered their subsistence practices to incorporate more wild meat and fewer grains into their diet. Although daily practices in the form of food procurement changed, infant burial practices remained constant from the Early Jorwe (1400 B.c.-lOOO B.C.) to the Late Jorwe (1000 B.c.-700 B.C.) period. Examining interments together with subsistence strategies firmly situates ideational practices within the fabric of daily life. This paper will explore the relationship between change and continuity in burial and subsistence practices around 1000 B.C. at the previously excavated Cha1colithic site of Inamgaon in the western Deccan (Fig. 1). By considering the act of burial as a moment of social construction that both creates and reflects larger traditions, it is possible to understand how each individual interment affects chronological variability. That burial traditions at Inamgaon were continuously recreated in the face of a changing society suggests that meaningful and significant practices were actively upheld. Burial practices at Inamgaon were both structured and fluid enough to allow room for individual and group expression. The con temporaneous variability that occurs in the burial record at Inamgaon may reflect the marking of various aspects of personhood. Burial traditions and the ability and desire of the living to conforITl to them vary over time and it is important to consider the specific social context in which they occur.