Sir John and Lady Rita Cornforth: a Distinguished Chemical Partnership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RSC Branding

Royal Society of Chemistry National Chemical Landmarks Award Honouree Location Inscription Date The Institute of Cancer Research, Chester ICR scientists on this site and elsewhere pioneered numerous new cancer drugs from 10 Institute of Cancer Beatty Laboratories, 237 the 1950s until the present day – including the discovery of chemotherapy drug December Research Fulham Road, Chelsea carboplatin, prostate cancer drug abiraterone and the genetic targeting of olaparib for 2018 Road, London, SW3 ovarian and breast cancer. 6JB, UK The Institute of Cancer ICR scientists on this site and elsewhere pioneered numerous new cancer drugs from 10 Research, Royal Institute of Cancer the 1950s until the present day – including the discovery of chemotherapy drug December Marsden Hospital, 15 Research carboplatin, prostate cancer drug abiraterone and the genetic targeting of olaparib for 2018 Cotswold Road, Sutton, ovarian and breast cancer. London, SM2 5NG, UK Ape and Apple, 28-30 John Dalton Street was opened in 1846 by Manchester Corporation in honour of 26 October John Dalton Street, famous chemist, John Dalton, who in Manchester in 1803 developed the Atomic John Dalton 2016 Manchester, M2 6HQ, Theory which became the foundation of modern chemistry. President of Manchester UK Literary and Philosophical Society 1816-1844. Chemical structure of Near this site in 1903, James Colquhoun Irvine, Thomas Purdie and their team found 30 College Gate, North simple sugars, James a way to understand the chemical structure of simple sugars like glucose and lactose. September Street, St Andrews, Fife, Colquhoun Irvine and Over the next 18 years this allowed them to lay the foundations of modern 2016 KY16 9AJ, UK Thomas Purdie carbohydrate chemistry, with implications for medicine, nutrition and biochemistry. -

Robert Burns Woodward

The Life and Achievements of Robert Burns Woodward Long Literature Seminar July 13, 2009 Erika A. Crane “The structure known, but not yet accessible by synthesis, is to the chemist what the unclimbed mountain, the uncharted sea, the untilled field, the unreached planet, are to other men. The achievement of the objective in itself cannot but thrill all chemists, who even before they know the details of the journey can apprehend from their own experience the joys and elations, the disappointments and false hopes, the obstacles overcome, the frustrations subdued, which they experienced who traversed a road to the goal. The unique challenge which chemical synthesis provides for the creative imagination and the skilled hand ensures that it will endure as long as men write books, paint pictures, and fashion things which are beautiful, or practical, or both.” “Art and Science in the Synthesis of Organic Compounds: Retrospect and Prospect,” in Pointers and Pathways in Research (Bombay:CIBA of India, 1963). Robert Burns Woodward • Graduated from MIT with his Ph.D. in chemistry at the age of 20 Woodward taught by example and captivated • A tenured professor at Harvard by the age of 29 the young... “Woodward largely taught principles and values. He showed us by • Published 196 papers before his death at age example and precept that if anything is worth 62 doing, it should be done intelligently, intensely • Received 24 honorary degrees and passionately.” • Received 26 medals & awards including the -Daniel Kemp National Medal of Science in 1964, the Nobel Prize in 1965, and he was one of the first recipients of the Arthur C. -

St Catherine's College Oxford

MESSAGES The Year St Catherine’s College . Oxford 2013 ST CATHERINE’S COLLEGE 2013/75 MESSAGES Master and Fellows 2013 MASTER Susan C Cooper, MA (BA Richard M Berry, MA, DPhil Bart B van Es (BA, MPhil, Angela B Brueggemann, Gordon Gancz, BM BCh, MA Collby Maine, PhD California) Tutor in Physics PhD Camb) DPhil (BSc St Olaf, MSc Fellow by Special Election Professor Roger W Professor of Experimental Reader in Condensed Tutor in English Iowa) College Doctor Ainsworth, MA, DPhil, Physics Matter Physics Senior Tutor Fellow by Special Election in FRAeS Biological Sciences Geneviève A D M Peter R Franklin, MA (BA, Ashok I Handa, MA (MB BS Tommaso Pizzari, MA (BSc Wellcome Trust Career Helleringer (Maîtrise FELLOWS DPhil York) Lond), FRCS Aberd, PhD Shef) Development Fellow ESSEC, JD Columbia, Maîtrise Tutor in Music Fellow by Special Election in Tutor in Zoology Sciences Po, Maîtrise, Richard J Parish, MA, DPhil Professor of Music Medicine James E Thomson, MChem, Doctorat Paris-I Panthéon- (BA Newc) Reader in Surgery Byron W Byrne, MA, DPhil DPhil Sorbonne, Maîtrise Paris-II Tutor in French John Charles Smith, MA Tutor for Graduates (BCom, BEng Western Fellow by Special Election in Panthéon-Assas) Philip Spencer Fellow Tutor in French Linguistics Australia) Chemistry Fellow by Special Election Professor of French President of the Senior James L Bennett, MA (BA Tutor in Engineering Science in Law (Leave H14) Common Room Reading) Tutor for Admissions Andrew J Bunker, MA, DPhil Leverhulme Trust Early Fellow by Special Election Tutor in Physics -

Sir John Warcup Cornforth

Sir John Warcup Cornforth The degree of Doctor of Science (honoris causa) was conferred upon Sir John Warcup Cornforth at a ceremony held in the Great Hall on 2 November 1977. Sir John Warcup Cornforth, photo G3_224_1122, University of Sydney Archives. Citation A Nobel Prize-winning chemist who has been totally deaf for the past 40 years will be awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Science by the University at a cemony in the Great Hall next Wednesday, November 2, 1977. He is Sir John Cornforth, 60, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1975 for his work on the stereochemistry of enzyme-catalysed reactions. He is currently the Royal Society Research Professor at the University of Sussex, and during his four-week visit to Australia he will deliver lectures in Sydney, Canberra, Melbourne and Adelaide. Sir John entered this University at the age of 16. The first signs of his deafness (from otosclerosis) had begun when he was 10, and although he had been able to profit from teaching at Sydney Boys' School, he was unable to hear any lecture at the University. He was, however, attracted by laboratory work in organic chemistry (which he had done in an improvised laboratory at home since the age of 14) and by the availability of original chemical literature. In 1937 he graduated with first-class honours and the University medal. After a year of postgraduate research he won a scholarship to work at Oxford. Two such scholarships were awarded each year, and the other was won by Rita Harradence, also of Sydney and also a winner of the University medal. -

Robert Burns Woodward 1917–1979

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ROBERT BURNS WOODWARD 1917–1979 A Biographical Memoir by ELKAN BLOUT Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoirs, VOLUME 80 PUBLISHED 2001 BY THE NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS WASHINGTON, D.C. ROBERT BURNS WOODWARD April 10, 1917–July 8, 1979 BY ELKAN BLOUT OBERT BURNS WOODWARD was the preeminent organic chemist Rof the twentieth century. This opinion is shared by his colleagues, students, and by other distinguished chemists. Bob Woodward was born in Boston, Massachusetts, and was an only child. His father died when Bob was less than two years old, and his mother had to work hard to support her son. His early education was in the Quincy, Massachusetts, public schools. During this period he was allowed to skip three years, thus enabling him to finish grammar and high schools in nine years. In 1933 at the age of 16, Bob Woodward enrolled in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to study chemistry, although he also had interests at that time in mathematics, literature, and architecture. His unusual talents were soon apparent to the MIT faculty, and his needs for individual study and intensive effort were met and encouraged. Bob did not disappoint his MIT teachers. He received his B.S. degree in 1936 and completed his doctorate in the spring of 1937, at which time he was only 20 years of age. Immediately following his graduation Bob taught summer school at the University of Illinois, but then returned to Harvard’s Department of Chemistry to start a productive period with an assistantship under Professor E. -

Historical Group

Historical Group NEWSLETTER and SUMMARY OF PAPERS No. 67 Winter 2015 Registered Charity No. 207890 COMMITTEE Chairman: Dr J A Hudson ! Dr C Ceci (RSC) Graythwaite, Loweswater, Cockermouth, ! Dr N G Coley (Open University) Cumbria, CA13 0SU ! Dr C J Cooksey (Watford, Hertfordshire) [e-mail [email protected]] ! Prof A T Dronsfield (Swanwick, Secretary: Prof. J. W. Nicholson ! Derbyshire) 52 Buckingham Road, Hampton, Middlesex, ! Prof E Homburg (University of TW12 3JG [e-mail: [email protected]] ! Maastricht) Membership Prof W P Griffith ! Prof F James (Royal Institution) Secretary: Department of Chemistry, Imperial College, ! Dr M Jewess (Harwell, Oxon) London, SW7 2AZ [e-mail [email protected]] ! Dr D Leaback (Biolink Technology) Treasurer: Dr P J T Morris ! Mr P N Reed (Steensbridge, Science Museum, Exhibition Road, South ! Herefordshire) Kensington, London, SW7 2DD ! Dr V Quirke (Oxford Brookes University) [e-mail: [email protected]] !Prof. H. Rzepa (Imperial College) Newsletter Dr A Simmons !Dr A Sella (University College) Editor Epsom Lodge, La Grande Route de St Jean, St John, Jersey, JE3 4FL [e-mail [email protected]] Newsletter Dr G P Moss Production: School of Biological and Chemical Sciences, Queen Mary University of London, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS [e-mail [email protected]] http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/rschg/ http://www.rsc.org/membership/networking/interestgroups/historical/index.asp 1 RSC Historical Group Newsletter No. 67 Winter 2015 Contents From the Editor 2 ROYAL SOCIETY OF CHEMISTRY HISTORICAL GROUP NEWS The Life and Work of Sir John Cornforth CBE AC FRS 3 Royal Society of Chemistry News 4 Feedback from the Summer 2014 Newsletter – Alwyn Davies 4 Another Object to Identify – John Nicholson 4 Published Histories of Chemistry Departments in Britain and Ireland – Bill Griffith 5 SOCIETY NEWS News from the Historical Division of the German Chemical Society – W.H. -

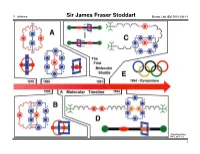

Sir James Fraser Stoddart Baran Lab GM 2010-08-14

Y. Ishihara Sir James Fraser Stoddart Baran Lab GM 2010-08-14 (The UCLA USJ, 2007, 20, 1–7.) 1 Y. Ishihara Sir James Fraser Stoddart Baran Lab GM 2010-08-14 (The UCLA USJ, 2007, 20, 1–7.) 2 Y. Ishihara Sir James Fraser Stoddart Baran Lab GM 2010-08-14 Professor Stoddart's publication list (also see his website for a 46-page publication list): - 9 textbooks and monographs - 13 patents "Chemistry is for people - 894 communications, papers and reviews (excluding book chapters, conference who like playing with Lego abstracts and work done before his independent career, the tally is about 770) and solving 3D puzzles […] - At age 68, he is still very active – 22 papers published in the year 2010, 8 months in! Work is just like playing - He has many publications in so many fields... with toys." - Journals with 10+ papers: JACS 75 Acta Crystallogr Sect C 26 ACIEE 67 JCSPT1 23 "There is a lot of room for ChemEurJ 62 EurJOC 19 creativity to be expressed JCSCC 51 ChemComm 15 in chemis try by someone TetLett 42 Carbohydr Res 12 who is bent on wanting to OrgLett 35 Pure and Appl Chem 11 be inventive and make JOC 28 discoveries." - High-profile general science journals: Nature 4 Science 5 PNAS 8 - Reviews: AccChemRes 8 ChemRev 4 ChemSocRev 6 - Uncommon venues of publication for British or American scientists: Coll. Czechoslovak Chem. Comm. 5 Mendeleev Communications 2 Israel Journal of Chemistry 5 Recueil des Trav. Chim. des Pays-Bas 2 Canadian Journal of Chemistry 4 Actualité chimique 1 Bibliography (also see his website, http://stoddart.northwestern.edu/ , for a 56-page CV): Chemistry – An Asian Journal 3 Bulletin of the Chem. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6* x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Leading Research for Better Health

< Contents > Contents Please click on the > to go directly to the page. > Introducing the MRC >AchievementsIntroducing thetimeline MRC Achievements>1913 to 1940s timeline >1950s to 1980s >1913 to 1940s >1990s to 2006 >1950s to 1980s >1990s to 2006 > Leading research for better health >NobelLeading Prize resear timelinech for better health Nobel>1929 Prizeto 1952 timeline >1953 to 1962 >1929 to 1952 >1972 to 1984 >1953 to 1962 >1997 to 2003 >1972 to 1984 1997 to 2003 >MRC research over the decades MRC> From resear discochvery over to healthcare:the decades translational research > EvidenceFrom discovery for best to pr healthcareactice: clinical — translational trials research > EvidencePublic health for bestresearch practice: clinical trials > PubDNAlic revhealtholution research > ReducingDNA rev olutionsmoking: preventing deaths > ReducingTherapeutic smoking: antibodiespreventing deaths > TherapeuticReducing deaths antibodies from infections in Africa > ReducingPreventing deaths heart fromdisease infections in Africa > PrevMedicalenting imaging: hearttransformingdisease diagnosis > MedicalCutting childimaging: leukaemia transforming deaths diagnosis > Cutting child leukaemia deaths < Click on any link to go< directly Contentsto a page >> < Contents > < Contents > < Contents > < Contents > Leading research for better health The most important part of the MRC’s mission trials, such as those on the use of statins to lower is to encourage and support high-quality research cholesterol and on vaccines in Africa.The MRC with the aim of improving human health.The MRC is the UK’s largest public funder of clinical trials is committed to supporting research across the and it supports some of the most productive entire spectrum of the biomedical and clinical and ambitious epidemiological studies in the world, sciences. We are proud of our international including the UK Biobank. -

List of Nobel Laureates 1

List of Nobel laureates 1 List of Nobel laureates The Nobel Prizes (Swedish: Nobelpriset, Norwegian: Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institute, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make outstanding contributions in the fields of chemistry, physics, literature, peace, and physiology or medicine.[1] They were established by the 1895 will of Alfred Nobel, which dictates that the awards should be administered by the Nobel Foundation. Another prize, the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, was established in 1968 by the Sveriges Riksbank, the central bank of Sweden, for contributors to the field of economics.[2] Each prize is awarded by a separate committee; the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awards the Prizes in Physics, Chemistry, and Economics, the Karolinska Institute awards the Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee awards the Prize in Peace.[3] Each recipient receives a medal, a diploma and a monetary award that has varied throughout the years.[2] In 1901, the recipients of the first Nobel Prizes were given 150,782 SEK, which is equal to 7,731,004 SEK in December 2007. In 2008, the winners were awarded a prize amount of 10,000,000 SEK.[4] The awards are presented in Stockholm in an annual ceremony on December 10, the anniversary of Nobel's death.[5] As of 2011, 826 individuals and 20 organizations have been awarded a Nobel Prize, including 69 winners of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.[6] Four Nobel laureates were not permitted by their governments to accept the Nobel Prize. -

Image-Brochure-LNLM-2020-LQ.Pdf

NOBEL LAUREATES PARTICIPATING IN LINDAU EVENTS SINCE 1951 Peter Agre | George A. Akerlof | Kurt Alder | Zhores I. Alferov | Hannes Alfvén | Sidney Altman | Hiroshi Amano | Philip W. Anderson | Christian B. Anfinsen | Edward V. Appleton | Werner Arber | Frances H. Arnold | Robert J. Aumann | Julius Axelrod | Abhijit Banerjee | John Bardeen | Barry C. Barish | Françoise Barré-Sinoussi | Derek H. R. Barton | Nicolay G. Basov | George W. Beadle | J. Georg Bednorz | Georg von Békésy |Eric Betzig | Bruce A. Beutler | Gerd Binnig | J. Michael Bishop | James W. Black | Elizabeth H. Blackburn | Patrick M. S. Blackett | Günter Blobel | Konrad Bloch | Felix Bloch | Nicolaas Bloembergen | Baruch S. Blumberg | Niels Bohr | Max Born | Paul Boyer | William Lawrence Bragg | Willy Brandt | Walter H. Brattain | Bertram N. Brockhouse | Herbert C. Brown | James M. Buchanan Jr. | Frank Burnet | Adolf F. Butenandt | Melvin Calvin Thomas R. Cech | Martin Chalfie | Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar | Pavel A. Cherenkov | Steven Chu | Aaron Ciechanover | Albert Claude | John Cockcroft | Claude Cohen- Tannoudji | Leon N. Cooper | Carl Cori | Allan M. Cormack | John Cornforth André F. Cournand | Francis Crick | James Cronin | Paul J. Crutzen | Robert F. Curl Jr. | Henrik Dam | Jean Dausset | Angus S. Deaton | Gérard Debreu | Petrus Debye | Hans G. Dehmelt | Johann Deisenhofer Peter A. Diamond | Paul A. M. Dirac | Peter C. Doherty | Gerhard Domagk | Esther Duflo | Renato Dulbecco | Christian de Duve John Eccles | Gerald M. Edelman | Manfred Eigen | Gertrude B. Elion | Robert F. Engle III | François Englert | Richard R. Ernst Gerhard Ertl | Leo Esaki | Ulf von Euler | Hans von Euler- Chelpin | Martin J. Evans | John B. Fenn | Bernard L. Feringa Albert Fert | Ernst O. Fischer | Edmond H. Fischer | Val Fitch | Paul J. -

HSNS4803 02 Heplersmith 300..337

EVAN HEPLER-SMITH* ‘‘A Way of Thinking Backwards’’: Computing and Method in Synthetic Organic Chemistry ABSTRACT This article addresses the history of how chemists designed syntheses of complex molecules during the mid-to-late twentieth century, and of the relationship between devising, describing, teaching, and computerizing methods of scientific thinking in this domain. It details the development of retrosynthetic analysis, a key method that chemists use to plan organic chemical syntheses, and LHASA (Logic and Heuristics Applied to Synthetic Analysis), a computer program intended to aid chemists in this task. The chemist E. J. Corey developed this method and computer program side-by-side, from the early 1960s through the 1990s. Although the LHASA program never came into widespread use, retrosynthetic analysis became a standard method for teaching and practicing synthetic planning, a subject previously taken as resistant to generalization. This article shows how the efforts of Corey and his collaborators to make synthetic planning tractable to teaching and to computer automation shaped a way of thinking taken up by chemists, unaided by machines. The method of retrosynthetic analysis made chemical thinking (as Corey perceived it) explicit, in accordance with the demands of computing (as Corey and his LHASA collaborators perceived them). This history of automation and method-making in recent chemistry suggests a potentially productive approach to the study of other projects to think on, with, or like machines. KEY WORDS: synthesis, organic chemistry, artificial intelligence, method, pedagogy, computing, LHASA, E. J. Corey *Harvard University Center for the Environment and Department of History of Science, 1 Oxford Street SC 371, Cambridge, MA 02138, [email protected].