Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pennsylvania Assembly's Conflict with the Penns, 1754-1768

Liberty University “The Jaws of Proprietary Slavery”: The Pennsylvania Assembly’s Conflict With the Penns, 1754-1768 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the History Department in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in History by Steven Deyerle Lynchburg, Virginia March, 2013 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1: Liberty or Security: Outbreak of Conflict Between the Assembly and Proprietors ......9 Chapter 2: Bribes, Repeals, and Riots: Steps Toward a Petition for Royal Government ..............33 Chapter 3: Securing Privilege: The Debates and Election of 1764 ...............................................63 Chapter 4: The Greater Threat: Proprietors or Parliament? ...........................................................90 BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................................................................................................113 1 Introduction In late 1755, the vituperative Reverend William Smith reported to his proprietor Thomas Penn that there was “a most wicked Scheme on Foot to run things into Destruction and involve you in the ruins.” 1 The culprits were the members of the colony’s unicameral legislative body, the Pennsylvania Assembly (also called the House of Representatives). The representatives held a different opinion of the conflict, believing that the proprietors were the ones scheming, in order to “erect their desired Superstructure of despotic Power, and reduce to -

1891 Census of Thanet Places As Enumerated, with Index

1891 Census of Thanet Places as Enumerated, with Index Scope The full Registration District, piece RG12/725 to piece RG12/733 inclusive. Arrangement A summary of the places-related information recorded in the enumerators’ returns of households, in ‘as enumerated’ order, including all Thanet’s public houses and farm houses (although some of these are not explicitly identified in the original). Each entry includes : • piece and folio numbers : used with the PRO class (RG12) to locate the original • Dwelling : name of one or more dwellings ~ 'Rows' and 'Terraces' are usually under this heading, although some may have been considered 'streets' and their names used as street names • Street : names of a street, road, etc, and some hamlets ~ 'Places' are usually under this heading, although some may have been sub-divisions of a street • parish : the ecclesiastical parish, abbreviated as noted below • locality : the key guide to location, used to differentiate common street names in the Index There is a combined Index for Dwellings and Streets starting on page 56, each entry giving a piece and folio number(s). Abbreviations & Notations [ ] square brackets enclose annotation { } where a place-name spelling may be incorrect, the accepted version is given and the original enclosed in curly brackets ~ usually both are indexed *** unoccupied/being built, usually only noted if the name of a dwelling or street would otherwise be omitted aS All Saints, Birchington cC Christ Church, Ramsgate hT Holy Trinity, Broadstairs hTm Holy Trinity, Margate hTr Holy -

2013 Report (Pdf, 2889KB)

Local Development Framework AMR 10 for financial year 2012/13 London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Authority’s Monitoring Report 10 for financial year 2012/13 December 2013 Produced by Policy & Research Section, Planning Dept Contact – [email protected] Produced by Policy & Research Section, Planning Dept Contact – [email protected], Local Development Framework AMR 10 for financial year 2012/13 Contents 1 Introduction..............................................................................................................................................1 2 Non-technical summary..........................................................................................................................3 3 Progress with the Local Development Framework..............................................................................5 4 The Indicators ..........................................................................................................................................8 4.1 Implementation of policies and proposals.................................................................................................................8 4.2 CP1: Sustainable Development..............................................................................................................................12 4.3 CP3: Climate Change.............................................................................................................................................22 4.4 CP4: Biodiversity....................................................................................................................................................29 -

Descriptive Sketches of Tunbridge Wells and the Calverley Estate

I^4S'0 Y R Af E D 1 ACCESSION NUMBER PRESS MARK 4 • j v. * * % % f Nl % * V . Xtie^\ Munfitiftti* vi ( \ 7uif>H/A \t.rtirt th/rfvrftvi J/tnmt lIp/irtiiM IfeOi/tittitti ZU'urt-^ TcnJ' xVtand We-sp^^an \fiir7tt •A^jA* portt*^9 ^Xnmxt Drami hy .1^ .W^Jiillm^s Enqmved W & ^Y\IL‘riSlFilLIlS"ro {’Th:e. trZothte tjfosvrnov VothuTe (alitHey Jiaiti J-’iirm 'ami 7 jf^ZriTt^Z^x.- Lath‘Zbtti.sn (i^toqe sons C ailverl i-y" ii^lL Stv/r of .y -y* ^J*•\brrt Y ^ y , y , , tons Topoqf'afihual Skrtches of TunbHttor /fo/I.r." : DESCRIPTIVE SKETCHES OF TUNBRIDGE WELLS AND THE CALVERLEY ESTATE; WITH BRIEF NOTICES OF THE PICTURESQUE SCENERY, SEATS, AND ANTIQUITIES IN THE VICINITY. lEmlieHisficti JWaps antJ prints. By JOHN BRITTON, F.S.A. AND OF OTHER ENGLISH AND FOREIGN SOCIETIES. LONDON PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR, BURTON STREET ; Sc CO. LONGMAN PATERNOSTER ROW ; AND RODWELL, NEW BOND STREET. SOLD BY NASH, AND BY ELLIOTT, TUNBRIDGE WELLS, &C. M.DCCC.XXXII : Ob (o LONDON 3. MOVES, CASTLE STREET, I.KtCFSTCR SQUARE- TO THE DUCHESS OF KENT, &c. See. Sec. Sec. MADAM, Presuming that there are circumstances and objects belonging to Tunbridge Wells closely associated with incidents in the juvenile life of the illustrious and amiable Princess, whose present hap- piness and future destinies your Royal Highness must contemplate with patriotic and maternal soli- citude, I venture to inscribe this small Volume to you, and remain Your Royal Highness s Obedient Servant, JOHN BRITTON. Febrtiarx) . 18 , 1832 . 'f 1 X * i . -

The Colonist

THE COLONIST. Vol. I.] DEMICR AR A, THURSDAY, DECEMBER II, 1823. [No. 27. ■rea.-si I i m/hiTilini G. O. FOR HIRE, FOR LONDON, Adjutant-General’s Office, . HE BUILDINGS situate on Lot No. 58, near to the House an ^ie ^th of January, Head-Quarters, Georgetown, December Q, 1823. T of A. Walstab, Esq. in Werk-en-Rust district, (lately be The fine Ship RICHARD, longing to, and occupied by, J. Horsley, dec.) comprising1 Ona Thursday, Friday, and Saturday, the 11th, 12th, and 13th of James Williamson, Master. For Passage only* IS Excellency the Commander-in-Chief has been pleased to0 Dwelling-House, with two halls below, and two chambers above,> December, by order of Campbell, M‘Kenzie, and Co. at their apply to Captain Williamson, or H make the following Promotions in the Demerara Militia“- with front and back galleries ; recently repaired and painted. A Store, without reserve, ' ' M‘DONALD, EDMONSTONE, and Co. range of Side Buildings, containing a good brick kitchen and oven, INED and unlined jackets, women’s wrappers, oznaburg pet 11th December, 1823. RIFLE CORPS, and five comfortable negro rooms, also in good order; with two wa- ticoats, Russia duck and blue trowsers, red flannel and check ter vats. For particulars, apply on the Premises. Second Lieutenant Alexander Shepherd, to be First Lieute Lshirts, tradesmen’s and negro hats, large sized blankets, strong linen FOR LIVERPOOL, nant. 8th December, 1823. checks, Strelitz oznaburgs, chambreys, Irish linen and diaper, mull leave the Bar on the 20th December, Sergeant Andrew Davidson, to be Second Lieutenant, vice■e ----------------- ---------------------------------------------------------- ------ -—- and jaconet muslins, flounced muslin dresses, furniture chintz, The Ship CORNWALL, R. -

The General Stud Book : Containing Pedigrees of Race Horses, &C

^--v ''*4# ^^^j^ r- "^. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/generalstudbookc02fair THE GENERAL STUD BOOK VOL. II. : THE deiterol STUD BOOK, CONTAINING PEDIGREES OF RACE HORSES, &C. &-C. From the earliest Accounts to the Year 1831. inclusice. ITS FOUR VOLUMES. VOL. II. Brussels PRINTED FOR MELINE, CANS A.ND C"., EOILEVARD DE WATERLOO, Zi. M DCCC XXXIX. MR V. un:ve PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. To assist in the detection of spurious and the correction of inaccu- rate pedigrees, is one of the purposes of the present publication, in which respect the first Volume has been of acknowledged utility. The two together, it is hoped, will form a comprehensive and tole- rably correct Register of Pedigrees. It will be observed that some of the Mares which appeared in the last Supplement (whereof this is a republication and continua- tion) stand as they did there, i. e. without any additions to their produce since 1813 or 1814. — It has been ascertained that several of them were about that time sold by public auction, and as all attempts to trace them have failed, the probability is that they have either been converted to some other use, or been sent abroad. If any proof were wanting of the superiority of the English breed of horses over that of every other country, it might be found in the avidity with which they are sought by Foreigners. The exportation of them to Russia, France, Germany, etc. for the last five years has been so considerable, as to render it an object of some importance in a commercial point of view. -

The ^Penn Collection

The ^Penn Collection A young man, William Penn fell heir to the papers of his distinguished father, Admiral Sir William Penn. This collec- A tion, the foundation of the family archives, Penn carefully preserved. To it he added records of his own, which, with the passage of time, constituted a large accumulation. Just before his second visit to his colony, Penn sought to put the most pertinent of his American papers in order. James Logan, his new secretary, and Mark Swanner, a clerk, assisted in the prepara- tion of an index entitled "An Alphabetical Catalogue of Pennsylvania Letters, Papers and Affairs, 1699." Opposite a letter and a number in this index was entered the identifying endorsement docketed on the original manuscript, and, to correspond with this entry, the letter and number in the index was added to the endorsement on the origi- nal document. When completed, the index filled a volume of about one hundred pages.1 Although this effort showed order and neatness, William Penn's papers were carelessly kept in the years that followed. The Penn family made a number of moves; Penn was incapacitated and died after a long illness; from time to time, business agents pawed through the collection. Very likely, many manuscripts were taken away for special purposes and never returned. During this period, the papers were in the custody of Penn's wife; after her death in 1726, they passed to her eldest son, John Penn, the principal proprietor of Pennsylvania. In Philadelphia, there was another collection of Penn deeds, real estate maps, political papers, and correspondence. -

On the Laws and Practice of Horse Racing

^^^g£SS/^^ GIFT OF FAIRMAN ROGERS. University of Pennsylvania Annenherg Rare Book and Manuscript Library ROUS ON RACING. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/onlawspracticeOOrous ON THE LAWS AND PRACTICE HORSE RACING, ETC. ETC. THE HON^T^^^ ADMIRAL ROUS. LONDON: A. H. BAILY & Co., EOYAL EXCHANGE BUILDINGS, COENHILL. 1866. LONDON : PRINTED BY W. CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFORD STREET, AND CHAKING CROSS. CONTENTS. Preface xi CHAPTER I. On the State of the English Turf in 1865 , . 1 CHAPTER II. On the State of the La^^ . 9 CHAPTER III. On the Rules of Racing 17 CHAPTER IV. On Starting—Riding Races—Jockeys .... 24 CHAPTER V. On the Rules of Betting 30 CHAPTER VI. On the Sale and Purchase of Horses .... 44 On the Office and Legal Responsibility of Stewards . 49 Clerk of the Course 54 Judge 56 Starter 57 On the Management of a Stud 59 vi Contents. KACma CASES. PAGE Horses of a Minor Age qualified to enter for Plates and Stakes 65 Jockey changed in a Race ...... 65 Both Jockeys falling abreast Winning Post . 66 A Horse arriving too late for the First Heat allowed to qualify 67 Both Horses thrown—Illegal Judgment ... 67 Distinction between Plate and Sweepstakes ... 68 Difference between Nomination of a Half-bred and Thorough-bred 69 Whether a Horse winning a Sweepstakes, 23 gs. each, three subscribers, could run for a Plate for Horses which never won 50^. ..... 70 Distance measured after a Race found short . 70 Whether a Compromise was forfeited by the Horse omitting to walk over 71 Whether the Winner distancing the Field is entitled to Second Money 71 A Horse objected to as a Maiden for receiving Second Money 72 Rassela's Case—Wrong Decision ... -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Gaming Introduction/Schedule ...........................................4 Role Playing Games (Campaign) ........................................25 Board Gaming ......................................................................7 Campaign RPGs Grid ..........................................................48 Collectible Card Games (CCG) .............................................9 Role Playing Games (Non-Campaign) ................................35 LAN Gaming (LAN) .............................................................18 Non-Campaign RPGs Grid ..................................................50 Live Action Role Playing (LARP) .........................................19 Table Top Gaming (GAME) .................................................52 NDMG/War College (NDM) ...............................................55 Video Game Programming (VGT) ......................................57 Miniatures .........................................................................20 Maps ..................................................................................61 LOCATIONS Gaming Registration (And Help!) ..................................................................... AmericasMart Building 1, 2nd Floor, South Hall Artemis Spaceship Bridge Simulator ..........................................................................................Westin, 14th Floor, Ansley 7/8 Board Games ................................................................................................... AmericasMart Building 1, 2nd -

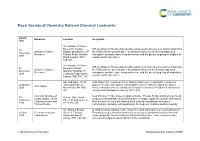

RSC Branding

Royal Society of Chemistry National Chemical Landmarks Award Honouree Location Inscription Date The Institute of Cancer Research, Chester ICR scientists on this site and elsewhere pioneered numerous new cancer drugs from 10 Institute of Cancer Beatty Laboratories, 237 the 1950s until the present day – including the discovery of chemotherapy drug December Research Fulham Road, Chelsea carboplatin, prostate cancer drug abiraterone and the genetic targeting of olaparib for 2018 Road, London, SW3 ovarian and breast cancer. 6JB, UK The Institute of Cancer ICR scientists on this site and elsewhere pioneered numerous new cancer drugs from 10 Research, Royal Institute of Cancer the 1950s until the present day – including the discovery of chemotherapy drug December Marsden Hospital, 15 Research carboplatin, prostate cancer drug abiraterone and the genetic targeting of olaparib for 2018 Cotswold Road, Sutton, ovarian and breast cancer. London, SM2 5NG, UK Ape and Apple, 28-30 John Dalton Street was opened in 1846 by Manchester Corporation in honour of 26 October John Dalton Street, famous chemist, John Dalton, who in Manchester in 1803 developed the Atomic John Dalton 2016 Manchester, M2 6HQ, Theory which became the foundation of modern chemistry. President of Manchester UK Literary and Philosophical Society 1816-1844. Chemical structure of Near this site in 1903, James Colquhoun Irvine, Thomas Purdie and their team found 30 College Gate, North simple sugars, James a way to understand the chemical structure of simple sugars like glucose and lactose. September Street, St Andrews, Fife, Colquhoun Irvine and Over the next 18 years this allowed them to lay the foundations of modern 2016 KY16 9AJ, UK Thomas Purdie carbohydrate chemistry, with implications for medicine, nutrition and biochemistry. -

Physicians and Surgeons Acheson, John 1875 Anglesey Villa, Outram Road, John Inglefield Acheson, MD 35 Aldous, Herbert James

Physicians and Surgeons http://www.pomeroyofportsmouth.uk/portsmouth-local-history.html Acheson, John 1875 Anglesey Villa, Outram Road, John Inglefield Acheson, MD 35 Aldous, Herbert James 1905 Leverton, 13 Yarborough Road, Herbert James Aldous, no trade listed 1 1911-1923 Leverton, 13 Yarborough Road, Herbert James Aldous, LRCS, LSA, Physician & Surgeon 1 Alexander, Samuel 1914 Devonshire House, 1 Grove Road South, Samuel Philip Alexander, MD, MRCS, Physician & Surgeon 1 1891 Tecumseh, Kent Road, Samuel Philip Alexander, MD, MRCS, Physician & Surgeon 1 1892-1899 Tecumseh, 20 Kent Road, Samuel Philip Alexander, MD, MRCS, Physician & Surgeon 1 1902-1917 20 Kent Road, Samuel Philip Alexander, MD, MRCS, Physician & Surgeon 1 1897-1901 2 Shaftesbury Road/Kent Road, Samuel Philip Alexander, MD, MRCS 1 Alford, Daniel 1875 Stanhope House, Ashburton Road, Daniel Alford, Surgeon 35 Alford, Samuel 1879 1 Richmond Terrace, Samuel Alford, MD 165 1881 Richmond Road, Samuel Alford, MD 165 Alford, W 1879 Warwick House, Clarence Parade, W.H Alford, MRCS, LSA 165 {Probably Axford} Allan, Walter Horace 1934-1937 1 Victoria Road North, Walter Horace Allan, MRCS, LRCP, Physician & Surgeon 1 1938-1948 Winkfield, 34 Victoria Road North, Walter Horace Allan, MRCS, LRCP, Physician & Surgeon 11 1951-1966 34 Victoria Road North, Walter Horace Allan, MRCS, LRCP, Physician & Surgeon 11 Allnut, Joseph F 1859 Mile End, Joseph F Allnut, Surgeon 59 1863 Commercial Road, J.F Allnut, Surgeon 63 1865 Herbert Street, Joseph Fenn Allnutt, Surgeon 1 1867 325 Commercial Road, -

Robert Burns Woodward

The Life and Achievements of Robert Burns Woodward Long Literature Seminar July 13, 2009 Erika A. Crane “The structure known, but not yet accessible by synthesis, is to the chemist what the unclimbed mountain, the uncharted sea, the untilled field, the unreached planet, are to other men. The achievement of the objective in itself cannot but thrill all chemists, who even before they know the details of the journey can apprehend from their own experience the joys and elations, the disappointments and false hopes, the obstacles overcome, the frustrations subdued, which they experienced who traversed a road to the goal. The unique challenge which chemical synthesis provides for the creative imagination and the skilled hand ensures that it will endure as long as men write books, paint pictures, and fashion things which are beautiful, or practical, or both.” “Art and Science in the Synthesis of Organic Compounds: Retrospect and Prospect,” in Pointers and Pathways in Research (Bombay:CIBA of India, 1963). Robert Burns Woodward • Graduated from MIT with his Ph.D. in chemistry at the age of 20 Woodward taught by example and captivated • A tenured professor at Harvard by the age of 29 the young... “Woodward largely taught principles and values. He showed us by • Published 196 papers before his death at age example and precept that if anything is worth 62 doing, it should be done intelligently, intensely • Received 24 honorary degrees and passionately.” • Received 26 medals & awards including the -Daniel Kemp National Medal of Science in 1964, the Nobel Prize in 1965, and he was one of the first recipients of the Arthur C.