Letras Classicas 11 Nota De Fim .Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded on 2017-02-12T05:23:19Z

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cork Open Research Archive Title Golden Age, Stone Age, Iron Age, Axial Age: The significance of archaic civilization for the modern world Author(s) Szakolczai, Árpád Publication date 2009-12 Original citation Szakolczai, A., 2009. Golden Age, Stone Age, Iron Age, Axial Age: The Significance of Archaic Civilization for the Modern World. In Center of Excellence Cultural Foundations of Integration, New Perspectives on Archaic Civilizations. Konstanz, Germany 8 – 9 Dec 2009. Type of publication Conference item Rights ©2010, Árpád Szakolczai http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/200 from Downloaded on 2017-02-12T05:23:19Z Szakolczai, A., 2009. Golden Age, Stone Age, Iron Age, Axial Age: The Significance of Archaic Civilization for the Modern World. In Center of Excellence Cultural Foundations of Integration, New Perspectives on Archaic Civilizations. Konstanz, Germany 8 – 9 Dec 2009. CORA Cork Open Research Archive http://cora.ucc.ie 1 Golden Age, Stone Age, Iron Age, Axial Age: The Significance of Archaic Civilization for the Modern World by Arpad Szakolczai School of Philosophy and Sociology University College, Cork Paper prepared for the workshop entitled ‘New Perspectives on Archaic Civilizations’, 8- 9 December 2009, organized by the Center of Excellence ‘Cultural Foundations of Integration’, University of Konstanz. Draft version; please, do not quote without permission. 2 Introduction Concerning the theme of the conference, from the perspective of the social sciences it seems to me that there are – and indeed can only be – two quite radically different positions. -

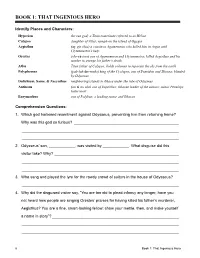

That Ingenious Hero

BOOK 1: THAT INGENIOUS HERO Identify Places and Characters: Hyperion the sun god; a Titan sometimes referred to as Helios Calypso daughter of Atlas; nymph on the island of Ogygia Aegisthus (ay-gis-thus) a cousin to Agamemnon who killed him in Argos with Clytemnestra’s help Orestes (ohr-es-teez) son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra; killed Aegisthus and his mother to avenge his father’s death Atlas Titan father of Calypso; holds columns to separate the sky from the earth Polyphemus (pah-luh-fee-muhs) king of the Cyclopes; son of Poseidon and Thoosa; blinded by Odysseus Dulichium, Same, & Zacynthus neighboring islands to Ithaca under the rule of Odysseus Antinous (an-ti-no-uhs) son of Eupeithes; Ithacan leader of the suitors; suitor Penelope hates most Eurymachus son of Polybus; a leading suitor and Ithacan Comprehension Questions: 1. Which god harbored resentment against Odysseus, preventing him from returning home? Why was this god so furious? ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ 2. Odysseus’ son, ____________, was visited by ____________. What disguise did this visitor take? Why? _________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ 3. Who sang and played the lyre for the rowdy crowd of suitors in the house of Odysseus? ________________________________________________________________________ -

The Iliad of Homer by Homer

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Iliad of Homer by Homer This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Iliad of Homer Author: Homer Release Date: September 2006 [Ebook 6130] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ILIAD OF HOMER*** The Iliad of Homer Translated by Alexander Pope, with notes by the Rev. Theodore Alois Buckley, M.A., F.S.A. and Flaxman's Designs. 1899 Contents INTRODUCTION. ix POPE'S PREFACE TO THE ILIAD OF HOMER . xlv BOOK I. .3 BOOK II. 41 BOOK III. 85 BOOK IV. 111 BOOK V. 137 BOOK VI. 181 BOOK VII. 209 BOOK VIII. 233 BOOK IX. 261 BOOK X. 295 BOOK XI. 319 BOOK XII. 355 BOOK XIII. 377 BOOK XIV. 415 BOOK XV. 441 BOOK XVI. 473 BOOK XVII. 513 BOOK XVIII. 545 BOOK XIX. 575 BOOK XX. 593 BOOK XXI. 615 BOOK XXII. 641 BOOK XXIII. 667 BOOK XXIV. 707 CONCLUDING NOTE. 747 Illustrations HOMER INVOKING THE MUSE. .6 MARS. 13 MINERVA REPRESSING THE FURY OF ACHILLES. 16 THE DEPARTURE OF BRISEIS FROM THE TENT OF ACHILLES. 23 THETIS CALLING BRIAREUS TO THE ASSISTANCE OF JUPITER. 27 THETIS ENTREATING JUPITER TO HONOUR ACHILLES. 32 VULCAN. 35 JUPITER. 38 THE APOTHEOSIS OF HOMER. 39 JUPITER SENDING THE EVIL DREAM TO AGAMEMNON. 43 NEPTUNE. 66 VENUS, DISGUISED, INVITING HELEN TO THE CHAMBER OF PARIS. -

Goethe and the Classical Ideal

GOETHE AND THE CLASSICAL IDEAL APPROVED! 2or Professor Minor Professor rector 6r the DeparMieKrt of History Deafa. of the Graduate School Eakin, Charles, Goethe and the Classical Ideal. Master of Arts (History)» May , 1973» 190 pp., bibliography* 148 titles« This thesis was written to examine Goethe*s efforts to emulate the Greeks and write in their spirit. Works most helpful in the stud# were Humphry Trevelyan's Goethe and, the Greeks, Kenry Hatfield's Aesthetic Paganism in German Literature, Eliza Butler's The Tyranny of Greece oyer Germany^ and the works of Goethe which show his relationship with the Greeks* The thesis opens with an examination of the nature and the philosophical implications of Goethe's emulation of the Greeks. Next Johann Winckelmann, the founder of Gorman Classical Hellenism is discussed, Winckelmann was exceedingly important in the founding and development of Goethe'a Classical Hellenism, for Winckelmann established a vision of Greece which influenced generations of German poets and scholars. The third chapter examines Goethe's perusal of Greek and Roman literature. Chapter IV deals with Goethe's conceptions of the Greeks during his youth. Goethe's earliest conceptions of the Greeks were colored not only by Winckelmann's Greek vision but also by the Storm and Stress movement. Goethe's Storm and Stress conception cf the Greeks emphasized the violentr titanic forces of ancient Greece. Although Goethe's earlier studies had made the Apollonian aspects of Greek culture overshadow the I Dionysian aspects of .Greece, he caiue after 1789 to realize the importance of the Dionysian* to a great extent# this! change was a reaction to the superficial interpretation of the Greeks "by Rococo Hellenism and its rejection of the Dionysian element. -

Artemis and Virginity in Ancient Greece

SAPIENZA UNIVERSITÀ DI ROMA FACOLTÀ DI LETTERE E FILOSOFIA DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN FILOLOGIA E STORIA DEL MONDO ANTICO XXVI CICLO ARTEMIS AND VIRGINITY IN ANCIENT GREECE TUTOR COTUTOR PROF. PIETRO VANNICELLI PROF. FRANCESCO GUIZZI 2 Dedication: To S & J with love and gratitude. Acknowledgements: I first and foremost wish to thank my tutor/advisor Professor Pietro Vannicelli and Co- Tutor Professor Francesco Guizzi for agreeing to serve in these capacities, for their invaluable advice and comments, and for their kind support and encouragement. I also wish to thank the following individuals who have lent intellectual and emotional support as well as provided invaluable comments on aspects of the thesis or offered advice and spirited discussion: Professor Maria Giovanna Biga, La Sapienza, and Professor Gilda Bartoloni, La Sapienza, for their invaluable support at crucial moments in my doctoral studies. Professor Emerita Larissa Bonfante, New York University, who proof-read my thesis as well as offered sound advice and thought-provoking and stimulating discussions. Dr. Massimo Blasi, La Sapienza, who proof-read my thesis and offered advice as well as practical support and encouragement throughout my doctoral studies. Dr. Yang Wang, Princeton University, who proof-read my thesis and offered many helpful comments and practical support. Dr. Natalia Manzano Davidovich, La Sapienza, who has offered intellectual, emotional, and practical support this past year. Our e-mail conversations about various topics related to our respective theses have -

The Iliad with an English Translation

®od^ ^.omertbe ju fctn, aud& nut aU lehtn, ift fc^en.-GoETHi HOMER THE ILIAD WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION A. T. MURRAY, Ph.D. PEOFESSOR OV CLASSICAL LITERATURK, STANFORD UNIVERSITIT, CALIFORNIA LONDON : WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD NEW YORK: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS MCMXXVIII CONTENTS OF VOLUME I Introduction Vil 2 Book I. 50 Book II. 116 Book III, 152 Book IV. Book V. 194 Book VI. 262 Book VIL 302 Book VIII. 338 Book IX. 382 Book X. 436 Book XL 480 Book XII, 544 INTRODUCTION In rendering the Iliad the translator has in the main followed the same principles as those which guided him in his translation of the Odyssey. He has endeavoured to give a version that in some measure retains the flowing ease and simple directness of Homer's style, and that has due regard to the emphasis attaching to the arrangement of words in the original ; and to make use of a diction that, while elevated, is, he trusts, not stilted. To attain to the nobility of Homer's manner may well be beyond the possibilities of modern English prose. Matters of a controversial nature have as a rule not been touched upon in the notes to this edition, and the brief bibhography is meant merely to sug- gest books of high interest and value to the student of the Iliad. Few of those which deal primarily with the higher criticism have been included, because the ti'anslator is convinced that such matters lie wholly outside the scope of this book. In the brief introduction prefixed to his version of the Odyssey the translator set forth frankly the fact that to many scholars it seems impossible to speak of Homer as a definite individual, or to accept the view that in the early period either the Iliad or the Odyssey had attained a fixed form. -

The Suitors' Treasure Trove: Un‐/Re‐Inscribing of Homer's Penelope In

NUML Journal of Critical Inquiry Vol 12 (1), June, 2014 ISSN 2222‐5706 The Suitors’ Treasure Trove: Un‐/Re‐inscribing of Homer’s Penelope in Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad Mirza Muhammad Zubair Baig Abstract Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad (2005) has attempted to reinscribe the stereotypical character of Penelope from Homer’s Odyssey (circa 800 BC). Her character has been presented as a prototype of faithful wife for the women of her times and, later on, throughout several generations, and across many boundaries and cultures in contrast with her heroic and legendary husband who was never questioned for his failure to fulfill the responsibilities of a husband and a father. This study focuses on how Penelope confronts Homer’s “nobler” version of her character that has glossed over the seamy side of her troubled life contextualized by her experiences with her father in Sparta, and with her husband and son in Ithaca. The retelling asserts how the “divine” queen has been ostracized right from her childhood. She was a plain girl and a woman conforming to the patriarchal standards but her wealth turned her into a prize for her husband and treasure trove for the suitors who besieged her day to day life. Her post‐body narration from the Hades, as her soul is now free from the earthly limitations and obligations, provides her free space for the expression of her concerns. By suspending readers’ disbelief, the narrative challenges the preconceived notions and images of The Odyssey. Her weaving of the King Laertes’, Odysseus’ father, shroud has been considered as a web of deception and commended as a trick to save her grace, secure her son’s vulnerability and defend her husband’s estate. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/23/2021 07:28:57PM Via Free Access 24 Chapter One Polytheism

CHAPTER ONE MANY GODS COMPLICATIONS OF POLYTHEISM Gods, gods, there are so many there’s no place left for a foot. Basavanna 1. Order versus Chaos Worn out by hardship, having drifted ashore after two nights and two days in the seething waves of a stormy sea, Odysseus is hungry. In his distress he addresses the first—and only—girl that meets his eyes with, as Homer Od. 6.149–153 reports, the gentle and cunning words: “Are you a goddess or a mortal woman? If a goddess, it is of Artemis that your form, stature, and figure εἶδός( τε μέγεθός τε φυήν) most remind me.” Not an unseasonable exordium under the circumstances. When, some 1300 years after this event, the inhabitants of the city of Lystra in the region of Lycaonia (Asia Minor) witnessed the apostles Paul and Barnabas preaching and working miracles, they took them to be gods in the likeness of men.1 Hungry too, or so they thought. So the priest of ‘Zeus who is before the city’ supplied oxen in order to bring a sacrifice in honour of their divine visitors,2 christening Barnabas Zeus and Paul Hermes because the latter “was the principal speaker,” as we read in the Acts of the Apostles. Hungry gods and deified mortals, as well as the interaction between rhetorical praise and religious language belong to the most captivat- ing phenomena of Greek religion. They will all return in later chap- ters of this book. The present chapter will be concerned with another theme prompted by these two charming anecdotes, namely that of 1 Acts 14.11: “The gods, having taken on human shape, have come down to us.” 2 Acts 14.13 mentions only θύειν, while 14.19 has θύειν αὐτοῖς (to sacrifice to them). -

Myth and Symbol I

Myth and Symbol I Symbolic phenomena in ancient Greek culture PAPERS FROM THE NORWEGIAN INSTITUTE AT ATHENS 1. The Norwegian Institute at Athens: The first five lectures. Ed. 0ivind Andersen and Helene Whittaker. Athens and Bergen, 1991. 86 pp. ISBN 960-85145-0-9. 2. Greece & Gender. Ed. Brit Berggreen and Nanno Marinatos. Bergen, 1995. 184 pp. ISBN 82-91626-oo-6. 3. Homer's world: Fiction, Tradition, Reality. Ed. 0ivind Andersen and Matthew Dickie. Bergen, 1995. 173 pp. ISBN 82-991411-9-2. 4· The world of ancient magic. Ed. David R. Jordan, Hugo Montgomery, Einar Thomas sen. Bergen, 1999. 335 pp. ISBN 82-91626-15-4. 5. Myth & symbol I. Symbolic phenomena in ancient Greek culture. Ed. Synnove des Bouvrie. Bergen, 2002. 333 pp. ISBN 82-91626-21-9. Front cover: 'The funeral games at the burial rites for Patroklos.' Attic black figure vase by Sophilos, early sixth century (Athens, nr. NAM 154 99, with the permission of the National Archaeological Museum) Papers from the Norwegian Institute at Athens 5 Myth and Symbol I Symbolic phenomena in ancient Greek culture Papers from the first international symposium on symbolism at the University ofTroms0, June 4-7,1998 Edited by Synn0ve des Bouvrie Bergen 2002 © The authors and The Norwegian Institute at Athens Composed in Minion and Symbol Greek Published with support from the Norwegian Research Council Distributor Paul Astroms Forlag William Gibsons vag 11 S-433 76 Jonsered Sweden The Norwegian Institute at Athens, 2002 ISSN 1105-4204 ISBN 82-91626-21-9 Printed in Norway 2002 John Grieg Grafisk AS, Bergen Contents Foreword 7 The definition of myth. -

The Bow and the Lyre: a Platonic Reading of the Odyssey

08-0302.Benardete.The Bow.qxd 9/11/08 6:09 AM Page 1 For orders and information please contact the publisher Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200 Lanham, Maryland 20706 1-800-462-6420 • www.rowmanlittlefield.com Cover design by Deborah Clark The Bow and the Lyre The Bow and the Lyre A Platonic Reading of the Odyssey Seth Benardete ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Published in the United States of America by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowmanlittlefield.com Estover Road Plymouth PL6 7PY United Kingdom Copyright ᭧ 1997 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. First paperback edition, 2008 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Cataloging in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Benardete, Seth. The bow and the lyre : a Platonic reading of the Odyssey / Seth Benardete. p. cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN–10 0–8476–8367–2 (cl. : alk. paper) ISBN–13 978–0–8476–8367–3 (cl. : alk. paper) ISBN–10: 0–7425–6596–3 (alk. paper) ISBN–13: 978–0–7425–6596–8 (alk. paper) eISBN–10: 0–7425–6597–1 eISBN–13: 978–0–7425–6597–5 1. Homer. Odyssey. 2. Odysseus (Greek mythology) in literature. -

When Were the Iliad and Odyssey Created? - a Late Bronze Age Story Recalled in Iron Age Times

When were the Iliad and Odyssey created? - A late Bronze Age story recalled in Iron Age times - (Relating to a Linked-in Discussion Group) “Mutating Genes in Homer”: Genomes and language provide clues on the origin of Homer's classic. Hosted by Ellie Rose Elliott 03.07.13 By Mel Copeland (response to Ellie Rose Elliott) Other clues in the dating of the Iliad and Odyssey involve the tradition of cremation and raising a tumulus over the dead, such as the case of Patroclus and Achilles (who was placed in the tumulus of Patroclus), the transition from bronze to iron, and mythological characters and their dating. The latest dated tumuli found in Greece might establish the latest date in which the Iliad could have been conceived, for the bard of the Iliad would not have remembered tumuli burials had they ceased to be practiced for several hundred years. Plutarch’s “Lives” – The life of Alexander – says that Alexander placed offerings at Achille’s “grave marker” when he visited Troy, that it was still there even in his day. The Greeks practiced shaft –grave inhumation (visible at Mycenae i.e., the Grave Circle) and cremation/tumuli burial. The Grave Circle is dated Late Helladic I, 1550-1500 B.C., and the tumuli are dated Late Helladic II (1500-1400). (Late Helladic III is 1400-1060 B.C.) By 1200 B.C. all of the Mycenaean cities had been destroyed. Pausanias’ book states that when he toured Mycenae a local guide showed him the tumulus of Agamemnon outside the walls (not within the Grave Circle). -

The Mycenaean Origin of Greek Mythology

THE MYCENAEAN ORIGIN OF GREEK MYTHOLOGY BY MARTIN P. NILSSON 1932 The Mycenaean Origin of Greek Mythology by Martin P. Nilsson. This edition was created and published by Global Grey ©GlobalGrey 2018 globalgreyebooks.com CONTENTS Chapter 1. How Old Is Greek Mythology? CHAPTER 2. MYCENAEAN CENTERS AND MYTHOLOGICAL CENTERS Introduction 1. Argolis 2. Laconia 3. The Dominion Of Pylos 4. The Rest Of The Peloponnese 5. The Ionian Islands 6. Southern Boeotia 7. Northern Boeotia And Thessaly 8. Attica 9. Conclusion Chapter 3. Heracles Chapter 4. Olympus 1 CHAPTER 1. HOW OLD IS GREEK MYTHOLOGY? The question: How old is Greek mythology? may at first sight seem idle, for Greek mythology is obviously of many different ages. For example, many genealogies and eponymous heroes created for political purposes are late, such inventions having been made through the whole historical age of Greece; yet most of them are earlier than the very late myths like the campaigns of Dionysus, or the great mass of the metamorphoses, especially the catasterisms, which were invented in the Hellenistic age. The great tragic poets reshaped the myths and left their imprint upon them, so that the forms in which the myths are commonly known nowadays often have been given them by tragedy. Similarly, before the tragic poets, the choric lyric poets reshaped them. The cyclical epics also are thought to have exercised a profound influence upon the remodeling of the myths. In Homer we find many well-known myths, often in forms differing, however, from those in which they are related later. Finally, it cannot be doubted that myths existed before Homer.