When Were the Iliad and Odyssey Created? - a Late Bronze Age Story Recalled in Iron Age Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Earliest Settlements at Eutresis Supplementary

THE EARLIESTSETTLEMENTS AT EUTRESIS SUPPLEMENTARYEXCAVATIONS, 1958 (PLATES 40-53) E UTRESIS in Boeotia, investigated by Hetty Goldman in the years 1924-1927, continues to be a principal source of our knowledge of the Bronze Age on the Greek mainland. It is a rich, well-stratified site; the excavations were conducted with skill and precision; and the definitive publication1 provides an admirably clear report of what was found. Although much of the hill was left untouched in the campaigns of the 1920's, the areas examined were sufficient to furnish reliable information about the Mycenaean and Middle Helladic settlements and about the remains of the three principal stages of Early Helladic habitations. Only the very earliest strata, lying on and just over virgin soil, proved relatively inaccessible. These were tested in six deep pits; 2 but owing to the presence of later structures, which were scrupulously respected by the excavators, the area at the bottom of the soundings was limited, amounting altogether to no more than 45 square meters. Two of the shafts revealed circular recesses cut in the hardpan, apparently the sites of huts; and the earliest deposits contained broken pottery of Neolithic types, mixed with relatively greater quantities of Early Helladic wares.3 The nature and significance of these earliest remains at Eutresis have been sub- jects of speculation during the past generation of prehistoric research. In the spring of 1958 Miss Goldman visited the site with the authors of this report and discussed the question again. It was agreed that a further test of the most ancient strata was worth undertaking, and a suitable region was noted for another deep sounding, con- siderably larger than any of the pits that had been excavated in 1927. -

Downloaded on 2017-02-12T05:23:19Z

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cork Open Research Archive Title Golden Age, Stone Age, Iron Age, Axial Age: The significance of archaic civilization for the modern world Author(s) Szakolczai, Árpád Publication date 2009-12 Original citation Szakolczai, A., 2009. Golden Age, Stone Age, Iron Age, Axial Age: The Significance of Archaic Civilization for the Modern World. In Center of Excellence Cultural Foundations of Integration, New Perspectives on Archaic Civilizations. Konstanz, Germany 8 – 9 Dec 2009. Type of publication Conference item Rights ©2010, Árpád Szakolczai http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/200 from Downloaded on 2017-02-12T05:23:19Z Szakolczai, A., 2009. Golden Age, Stone Age, Iron Age, Axial Age: The Significance of Archaic Civilization for the Modern World. In Center of Excellence Cultural Foundations of Integration, New Perspectives on Archaic Civilizations. Konstanz, Germany 8 – 9 Dec 2009. CORA Cork Open Research Archive http://cora.ucc.ie 1 Golden Age, Stone Age, Iron Age, Axial Age: The Significance of Archaic Civilization for the Modern World by Arpad Szakolczai School of Philosophy and Sociology University College, Cork Paper prepared for the workshop entitled ‘New Perspectives on Archaic Civilizations’, 8- 9 December 2009, organized by the Center of Excellence ‘Cultural Foundations of Integration’, University of Konstanz. Draft version; please, do not quote without permission. 2 Introduction Concerning the theme of the conference, from the perspective of the social sciences it seems to me that there are – and indeed can only be – two quite radically different positions. -

A Poor Pick of Pottery?

[Type here] UNIVERSITEIT VAN AMSTERDAM MA Thesis Supervisor Prof. V.V. Stissi KASTRAKI: A POOR PICK OF POTTERY? The Middle Helladic Problem – Reassessing Thessaly’s ‘Dark Age’ Table of Contents List of Figures 2 List of Appendix Material 3 Abstract 5 Introduction 6 (i) Introducing Kastraki- Between the Almiros and Sourpi Plains 9 Chapter One: 9 Excavation and Scholarship on Prehistoric Thessaly: Cultural Context Chapter Two: 15 The Middle Helladic Problem: Ceramics and Chronology Chapter Three: 24 A Thessalian Study: Researching Kastraki Chapter Four: 30 Results of 2016 Study Season: Fabric Groups and Parallels Conclusion 45 Appendix 45 (i) Catalogue 45 (ii) Illustrations 63 (iii) Photographs of Diagnostic Sherds 68 Bibliography 85 1 | P a g e List of Figures Figure 1: Google earth image showing the location of Kastraki, and its surrounding region. 4 Source: Map data 2016 Google Maps 2016 TerraMetrics Figure 2: Hand-drawn map of the Almiros/Sourpi region and surrounding landscape. 9 Source: Wace and Thompson (1912). Figure 1: Computational map of Kastraki (2000/48) and surrounding areas showing elevation. 11 Source: Jitte Waagen (2016). Figure 4: Mycenaean pottery illustrations from Mycenae. 17 Source: Mountjoy (1990), 247. Figure 5: The terrain of Kastraki (2000/48). 29 Source: Jitte Waagen (2016). Figure 6: Finds from the Kastraki excavation. 32 Source: Batziou-Efstathiou (2008), 300. Figure 7: Computational Map of the Kastraki survey area 36 Source: Jitte Waagen (2016). Figure 8: Basic hand-drawn map of survey area. 45 Source: Author (2016). 2 | P a g e List of Appendix Material (i) Catalogue 42 Section A: Photographs of Find-Spot Groupings 43 Section B: Part I 49 Part II 55 (ii) Illustrations 60 Illu. -

Getting Acquainted with the Myths Search the GML Advanced

Document belonging to the Greek Mythology Link, a web site created by Carlos Parada, author of Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology Characters • Places • Topics • Images • Bibliography • PDF Editions About • Copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. Getting acquainted with the myths Search the GML advanced Sections in this Page I. Getting acquainted with the myths II. Four "gateways" of mythology III. A strategy for reading the myths I. Getting acquainted with the myths What "getting acquainted" may mean We'll first try to clarify the meaning that the expression "getting acquainted" may have in this context: In a practical sense, I mean by "acquaintance" a general knowledge of the tales of mythology, including how they relate to each other. This concept includes neither analysis nor interpretation of the myths nor plunging too deep into one tale or another. In another sense, the expression "getting acquainted" has further implications that deserve elucidation: First of all, let us remember that we naturally investigate what we ignore, and not what we already know; accordingly, we set out to study the myths not because we feel we know them but because we feel we know nothing or very little about them. I mention this obvious circumstance because I believe that we should bear in mind that, in this respect, we are not in the same position as our remote ancestors, who may be assumed to have made their acquaintance with the myths more or less in the same way one learns one's mother tongue, and consequently did not have to study them in any way. -

CLASSICAL MYTHS Unit 3. the Trojan War

CLASSICAL MYTHS Unit 3. The Trojan War 1. The fragments below belong to the text you are about to read. Work in pairs to decide where they should go. a) the son of Thetis and Peleus b) the king of Troy c) but was destined never to be believed d) sister of Helen e) According to the legend, the son of Ilos was Laomedon, who was regarded as a cheat and a liar f) It was a formidable fleet and army which left the Greek shores to embark on the siege of Troy g) Odysseus decided it was time to use some guile h) a priest of Apollo i) Menelaus, in the other hand, lived happily for many years with Helen j) During the wedding festivities the uninvited Eris, goddess of Discord, threw down a golden apple k) whom Zeus had seduced when he came to her in the disguise of a swan l) The Greeks began sacking the city m) and dragged the body three times round the city wall behind his chariot n) the man the Greeks had left behind THE TROJAN WAR Greek legends tell of a 10-year war between the Greeks and the people of Troy in Asia Minor. Troy was said to have been founded by a man called Teucer who became its first king and under his great-great-grand-son, Ilos, it received the name Ilion _1_ . Apollo and Poseidon built a wall round Troy for him, but Laomedon refused to give them the payment he had promised. In revenge the gods sent a sea monster to ravage Troy but the hero Heracles promised to kill it on the condition that Laomedon gave him his horses. -

MYTHOLOGY – ALL LEVELS Ohio Junior Classical League – 2012 1

MYTHOLOGY – ALL LEVELS Ohio Junior Classical League – 2012 1. This son of Zeus was the builder of the palaces on Mt. Olympus and the maker of Achilles’ armor. a. Apollo b. Dionysus c. Hephaestus d. Hermes 2. She was the first wife of Heracles; unfortunately, she was killed by Heracles in a fit of madness. a. Aethra b. Evadne c. Megara d. Penelope 3. He grew up as a fisherman and won fame for himself by slaying Medusa. a. Amphitryon b. Electryon c. Heracles d. Perseus 4. This girl was transformed into a sunflower after she was rejected by the Sun god. a. Arachne b. Clytie c. Leucothoe d. Myrrha 5. According to Hesiod, he was NOT a son of Cronus and Rhea. a. Brontes b. Hades c. Poseidon d. Zeus 6. He chose to die young but with great glory as opposed to dying in old age with no glory. a. Achilles b. Heracles c. Jason d. Perseus 7. This queen of the gods is often depicted as a jealous wife. a. Demeter b. Hera c. Hestia d. Thetis 8. This ruler of the Underworld had the least extra-marital affairs among the three brothers. a. Aeacus b. Hades c. Minos d. Rhadamanthys 9. He imprisoned his daughter because a prophesy said that her son would become his killer. a. Acrisius b. Heracles c. Perseus d. Theseus 10. He fled burning Troy on the shoulder of his son. a. Anchises b. Dardanus c. Laomedon d. Priam 11. He poked his eyes out after learning that he had married his own mother. -

STONEFLY NAMES from CLASSICAL TIMES W. E. Ricker

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Perla Jahr/Year: 1996 Band/Volume: 14 Autor(en)/Author(s): Ricker William E. Artikel/Article: Stonefly names from classical times 37-43 STONEFLY NAMES FROM CLASSICAL TIMES W. E. Ricker Recently I amused myself by checking the stonefly names that seem to be based on the names of real or mythological persons or localities of ancient Greece and Rome. I had copies of Bulfinch’s "Age of Fable," Graves; "Greek Myths," and an "Atlas of the Ancient World," all of which have excellent indexes; also Brown’s "Composition of Scientific Words," And I have had assistance from several colleagues. It turned out that among the stonefly names in lilies’ 1966 Katalog there are not very many that appear to be classical, although I may have failed to recognize a few. There were only 25 in all, and to get even that many I had to fudge a bit. Eleven of the names had been proposed by Edward Newman, an English student of neuropteroids who published around 1840. What follows is a list of these names and associated events or legends, giving them an entomological slant whenever possible. Greek names are given in the latinized form used by Graves, for example Lycus rather than Lykos. I have not listed descriptive words like Phasganophora (sword-bearer) unless they are also proper names. Also omitted are geographical names, no matter how ancient, if they are easily recognizable today — for example caucasica or helenica. alexanderi Hanson 1941, Leuctra. -

The 'Trial by Water' in Greek Myth and Literature

Leeds International Classical Studies 7.1 (2008) ISSN 1477-3643 (http://www.leeds.ac.uk/classics/lics/) © Fiona McHardy The ‘trial by water’ in Greek myth and literature FIONA MCHARDY (ROEHAMPTON UNIVERSITY) ABSTRACT: This paper discusses the theme of casting ‘unchaste’ women into the sea as a punishment in Greek myth and literature. Particular focus will be given to the stories of Danaë, Augë, Aerope and Phronime, who are all depicted suffering this punishment at the hands of their fathers. While Seaford (1990) has emphasized the theme of imprisonment which occurs in some of the stories involving the ‘floating chest’, I turn my attention instead to the theme of the sea. The coincidence in these stories of the threat of drowning for apparent promiscuity or sexual impurity with the escape of those girls who are innocent can be explained by the phenomenon of the ‘trial by water’ as evidenced in Babylonian and other early law codes (cf. Glotz 1904). Further evidence for this theory can be found in ancient novels where the trial of the heroine for sexual purity is often a key theme. The significance of chastity in the myths and in Athenian society is central to understanding the story patterns. The interrelationship of mythic and social ideals is drawn out in the paper. This paper examines the punishment of ‘unchaste’ women in Greek myth and literature, in particular their representation in Euripides’ fragmentary Augë, Cretan Women and Danaë. My focus is on punishments involving the sea, where it is possible to discern two interrelated strands in the tales.1 The first strand involves an angry parent condemning an errant daughter to be cast into the sea with the intention of drowning her. -

Theseus, Helen of Troy, and the House of Minos

Anistoriton Journal, vol. 11 (2008-2009) 1 Theseus, Helen of Troy, and the House of Minos By John Dana, B.A., M.L.S., M.A. Independent Scholar In February 2006 while on vacation, this author read Bettany Hughes' biography entitled Helen of Troy [1]. In Chapter 6, Ms. Hughes describes a liaison between a very young Helen and very old Theseus, king of Athens. Ms. Hughes' description generated the kernel of an idea. If Helen was about 12 years old and Theseus was about 50 years old at the time, then this incident occurred about 20 years before the beginning of the Trojan War -- assuming that Helen was about 30 years old when she journeyed to Troy. Theseus was alive about 20 years before the Trojan War! What an eye opening moment! If true, then what would be the approximate date when Theseus participated in Athens 3rd Tribute to Knossos [2] ? One could calculate an approximate date by constructing a time line or chronology. The second part of this short discourse is to use the time line. By constructing the time line one could discern something about Minos, King of Knossos. References to Minos abound , but they are somewhat contradictory. Sir Arthur Evans named a entire civilization -- the Minoan Civilization -- after him; this may have been a misnomer. There are also references to ethnicity – especially languages spoken on the Aegean Islands – relating to King Minos; these are crucial to gain an understanding of who were the Minoans and what was the Minoan Civilization. 1. The Trojan War. -- One crucial point in constructing the time line was assigning a date to the beginning of the Trojan War. -

Euripides and Gender: the Difference the Fragments Make

Euripides and Gender: The Difference the Fragments Make Melissa Karen Anne Funke A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Ruby Blondell, Chair Deborah Kamen Olga Levaniouk Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2013 Melissa Karen Anne Funke University of Washington Abstract Euripides and Gender: The Difference the Fragments Make Melissa Karen Anne Funke Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Ruby Blondell Department of Classics Research on gender in Greek tragedy has traditionally focused on the extant plays, with only sporadic recourse to discussion of the many fragmentary plays for which we have evidence. This project aims to perform an extensive study of the sixty-two fragmentary plays of Euripides in order to provide a picture of his presentation of gender that is as full as possible. Beginning with an overview of the history of the collection and transmission of the fragments and an introduction to the study of gender in tragedy and Euripides’ extant plays, this project takes up the contexts in which the fragments are found and the supplementary information on plot and character (known as testimonia) as a guide in its analysis of the fragments themselves. These contexts include the fifth- century CE anthology of Stobaeus, who preserved over one third of Euripides’ fragments, and other late antique sources such as Clement’s Miscellanies, Plutarch’s Moralia, and Athenaeus’ Deipnosophistae. The sections on testimonia investigate sources ranging from the mythographers Hyginus and Apollodorus to Apulian pottery to a group of papyrus hypotheses known as the “Tales from Euripides”, with a special focus on plot-type, especially the rape-and-recognition and Potiphar’s wife storylines. -

Patterns of Exchange and Mobility: the Case of the Grey Ware in Middle and Late Minoan Crete

PATTERNS OF EXCHANGE AND MOBILITY: THE CASE OF THE GREY WARE IN MIDDLE AND LATE MINOAN CRETE by LUCA GlRELLA * New finds and important contributions have recently offered a fresh overview on wheel-made grey ware on Crete and have also provided an occasion for an update on l pottery imported from outside Crete . As a result the list of Grey Ware (henceforth: GW) in LM III contexts has been expanded, but mentions of such a ware in previous periods have been surprisingly neglected. The aim of this article is to re-examine the evidence of the GW on Crete, from the first appearance of Grey Minyan Ware to the later distribution of GW up to the LM IIIC period (Fig. 1, Table 1)2. As will be understandable from the following overview, most of the information comes from old excavations and publications, when both the identification and terminology of this ware were far from being neatly recognizable (i.e. the use of term bucchero). As a second aim of this contribution, drawing upon GW circulation, we shall inquire into patterns of mobility and exchange; in fact, as a 'foreign ware', the phenomenon of GW on Crete can be the ideal theatre for the exploration of pottery and human mobility. For convenience's sake we shall distinguish four moments with distinct patterns of distribution: (1) the small scale world of the late Prepalatial period, when the unique Minyan bowl from Knossos - a MH I import - confirms the picture of the asymmetrical relationship between the Greek Mainland and Crete, which saw a large quantity of Minoan and Minoanizing pottery at coastal sites of southern and northeastern Peloponnese, but not the contrary. -

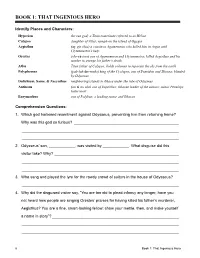

That Ingenious Hero

BOOK 1: THAT INGENIOUS HERO Identify Places and Characters: Hyperion the sun god; a Titan sometimes referred to as Helios Calypso daughter of Atlas; nymph on the island of Ogygia Aegisthus (ay-gis-thus) a cousin to Agamemnon who killed him in Argos with Clytemnestra’s help Orestes (ohr-es-teez) son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra; killed Aegisthus and his mother to avenge his father’s death Atlas Titan father of Calypso; holds columns to separate the sky from the earth Polyphemus (pah-luh-fee-muhs) king of the Cyclopes; son of Poseidon and Thoosa; blinded by Odysseus Dulichium, Same, & Zacynthus neighboring islands to Ithaca under the rule of Odysseus Antinous (an-ti-no-uhs) son of Eupeithes; Ithacan leader of the suitors; suitor Penelope hates most Eurymachus son of Polybus; a leading suitor and Ithacan Comprehension Questions: 1. Which god harbored resentment against Odysseus, preventing him from returning home? Why was this god so furious? ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ 2. Odysseus’ son, ____________, was visited by ____________. What disguise did this visitor take? Why? _________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ 3. Who sang and played the lyre for the rowdy crowd of suitors in the house of Odysseus? ________________________________________________________________________