Downloaded on 2017-02-12T05:23:19Z

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARCHAEOBOTANY in GREECE Alexandra Livarda, Department Of

ARCHAEOBOTANY IN GREECE Alexandra Livarda, Department of Archaeology, University of Nottingham, UK The final version of this paper can be found in the following publication: Livarda, A. 2014. Archaeobotany in Greece. Archaeological Reports 60: 106-116. This paper provides a brief overview of the history and the main achievements of archaeobotanical work in Greece to date, with the aim of highlighting its potential and creating a framework in which future work can be contextualised. The term ‘archaeobotany’ is used here in its narrow sense, referring to the study of plant macroremains, such as seeds, fruits and other plant parts, and excluding charcoal studies or ‘anthracology’ and analyses of microremains (e.g. pollen, phytoliths), which have developed to become separate sub-disciplines. From the first finds to a science Plant remains in the form of large concentrations of seeds, or individual finds of large specimens (known as spot finds), such as fruit stones, have been reported in the archaeological literature since the end of the nineteenth century. Botanical specimens that were occasionally unearthed caught the attention of archaeologists and site directors, who would either invite botanists or other experts to identify the species, or would simply rely on the expertise of the archaeological team, including that of local workers. A rather widely reported case is that of the early excavations at Knossos, where local workmen identified seeds found in a pithos as ‘Egyptian beans’, a variety of small fava beans imported to Crete from Alexandria at the end of the nineteenth century (Evans 1901, 20–21). At the other end of the spectrum, Schliemann (1886, 93), for instance, sent samples of the masses of burnt grains encountered in the early levels of Tiryns to an expert, Professor L. -

Biological Agriculture in Greece: Constraints and Opportunities for Development

BIOLOGICAL AGRICULTURE IN GREECE: CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR DEVELOPMENT By Leonidas Louloudis Department of Agricultural Economics and Development Agricultural University of Athens Paper presented to the Seminar: “The Common Agricultural Policy and the Environmental Challenge – New Tasks for the Public Administrations? European Institute of Public Administration (EIPA) Maastricht (NL), 145-15 May 2001 2 DRAFT PAPER (not to be quoted) BIOLOGICAL AGRICULTURE IN GREECE: CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR DEVELOPMENT Leonidas Louloudis Department of Agricultural Economics and Development Agricultural University of Athens Introduction Organic agriculture or biological agriculture, as it is called in Greece, does not account to more than 0.63% of the national agricultural output. But since the last food crisis (winter 2000) caused by the sudden re-appearance of the "mad-cow disease" in Europe, it has gained a new developmental momentum. The Greek press, although no incident of the Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy has been recorded so far within the national borders, covered this last food crisis extensively and devoted much space on the risks to human health, which were considered almost innate to the conventional agro-food system, and to the associated consumption and dietary patterns. In this historical conjuncture, biological agriculture entered the public debate through the mass media as the most immediate and radical solution to the industrial system of food production, which had lost its reliability almost entirely. The Ministry of Agriculture was not prepared to deal with such a severe crisis in the meat sector and thus to apply competently the measures against BSE, agreed upon at EU level. Thus it rushed to support that biological agriculture, and more specifically biological stockbreeding, is the only solution that guarantees a safe and healthy way out of the problem. -

Kron Food Production Docx

Supplementary Material 8 FOOD PRODUCTION (Expanded Version) Geoffrey Kron INTRODUCTION Although it would be attractive to offer a survey of agriculture throughout the ancient Mediterranean, the Near East, and those regions of temperate Europe, which were eventually incorporated into the Roman empire, I intend to concentrate primarily upon the best attested and most productive farming regime, that of Augustan Italy, 1 which was broadly comparable in its high level of intensification and agronomic sophistication with that of Greece, Western Asia Minor, North Africa, Baetica and Eastern Tarraconensis. Within the highly urbanized and affluent heartland of the Roman empire, our sources and archaeological evidence present a coherent picture of market-oriented intensive mixed farming, viticulture, arboriculture and market gardening, comparable, and often superior, in its productivity and agronomic expertise to the best agricultural practice of England, the Low Countries, France (wine), and Northern Italy in the mid 19th century. Greco- Roman farmers supplied a large urban population equal to, if not significantly greater than, that of early 19th century Italy and Greece, with a diet rich, not just in cereals, but in meat, wine, olive oil, fish, condiments, fresh fruit and vegetables. Anthropometric evidence of mean heights, derived from skeletal remains, reveal that protein and calorie malnutrition, caused by an insufficient diet based overwhelmingly on cereals, was very acute throughout 18th and 19th century Western Europe, and drove the mean -

Agricultural Practices in Ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman Period

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Hellenic University: IHU Open Access Repository Agricultural practices in ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman period Evangelos Kamanatzis SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies January 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece Student Name: Evangelos Kamanatzis SID: 2201150001 Supervisor: Prof. Manolis Manoledakis I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. January 2018 Thessaloniki - Greece Abstract This dissertation was written as part of the MA in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies at the International Hellenic University. The aim of this dissertation is to collect as much information as possible on agricultural practices in Macedonia from prehistory to Roman times and examine them within their social and cultural context. Chapter 1 will offer a general introduction to the aims and methodology of this thesis. This chapter will also provide information on the geography, climate and natural resources of ancient Macedonia from prehistoric times. We will them continue with a concise social and cultural history of Macedonia from prehistory to the Roman conquest. This is important in order to achieve a good understanding of all these social and cultural processes that are directly or indirectly related with the exploitation of land and agriculture in Macedonia through time. In chapter 2, we are going to look briefly into the origins of agriculture in Macedonia and then explore the most important types of agricultural products (i.e. -

Human Landscapes in Classical Antiquity

Leicester-Nottingham Studies in Ancient Society Volume 6 HUMAN LANDSCAPES IN CLASSICAL ANTIQUITY HUMAN LANDSCAPES IN CLASSICAL ANTIQUITY Environment and Culture Edited by GRAHAM SHIPLEY and JOHN SALMON London and New York First published 1996 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. Routledge is an International Thomson Publishing company Selection and editorial matter © 1996 Graham Shipley and John Salmon Individual chapters © 1996 the contributors All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data Human landscapes in classical antiquity: environment and culture/ edited by John Salmon and Graham Shipley. p. cm—(Leicester-Nottingham studies in ancient society: v. 6) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-415-10755-5 1. Greece—Civilization. 2. Rome—Civilization 3. Ecology— Greece—History. 4. Ecology—Rome—History. 5. Human ecology—Greece—History. 6. Human ecology—Rome—History. 7. Landscape—Greece—History. 8. Landscape—Rome—History. -

GREEK FOOD SOLIDARITIES (ALLILEGGIÍ) Communalism Vis-À-Vis Food in Crisis Greece

“NEW” GREEK FOOD SOLIDARITIES (ALLILEGGIÍ) Communalism vis-à-vis Food in Crisis Greece James Verinis, Roger Williams University, Bristol (USA) In this paper I extend the anthropological analyses of “new” solidarity (allileggií) networks or movements in Greece to rural regions and agricultural life as well as new groups of people. Food networks such as the “potato movement”, which facilitates the direct sales of agricultural produce, reveals rural aspects of networks that are thought to be simply urban phenomena. “Social kitch- ens” are revealed to be humanistic as well as nationalistic, bringing refugees, economic migrants, and Greeks together in arguably unprecedented ways. Through a review of such food solidarity movements – their rural or urban boundaries as well as their egalitarian or multicultural tenets – I consider whether they are thus more than mere extensions of earlier patterns of social solidarity identified in the anthropological record. Keywords: solidarity, rural–urban dichotomy, ethno-national identity, globalization, food “New” Greek Solidarity Movements well as the seemingly paradoxical evidence I had col- When I first began to reflect on the work I had con- lected during my dissertation fieldwork – that many ducted for my Ph.D. dissertation between 2008 and bonds between Greeks and non-Greeks in rural ar- 20101 in the southern Peloponnesian prefecture of eas had strengthened since the early 1990s.3 What is Laconia (which was primarily about Greek/non- more, to say that economic migrants are not simply Greek farmer relationships [Verinis 2015]), I sought exploited by neoliberalism is generally anathema to to account for some statistical evidence that many anthropology, despite its interest in data niches vis- non-Greeks had left Greece since the onset of the fi- à-vis qualitative approaches such as my focus on a nancial crisis.2 Mainstream media has focused heav- certain relatively small group of economic immi- ily on the rise of support for the Greek far right, par- grants. -

That Ingenious Hero

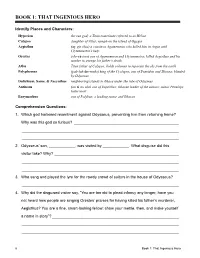

BOOK 1: THAT INGENIOUS HERO Identify Places and Characters: Hyperion the sun god; a Titan sometimes referred to as Helios Calypso daughter of Atlas; nymph on the island of Ogygia Aegisthus (ay-gis-thus) a cousin to Agamemnon who killed him in Argos with Clytemnestra’s help Orestes (ohr-es-teez) son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra; killed Aegisthus and his mother to avenge his father’s death Atlas Titan father of Calypso; holds columns to separate the sky from the earth Polyphemus (pah-luh-fee-muhs) king of the Cyclopes; son of Poseidon and Thoosa; blinded by Odysseus Dulichium, Same, & Zacynthus neighboring islands to Ithaca under the rule of Odysseus Antinous (an-ti-no-uhs) son of Eupeithes; Ithacan leader of the suitors; suitor Penelope hates most Eurymachus son of Polybus; a leading suitor and Ithacan Comprehension Questions: 1. Which god harbored resentment against Odysseus, preventing him from returning home? Why was this god so furious? ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ 2. Odysseus’ son, ____________, was visited by ____________. What disguise did this visitor take? Why? _________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ 3. Who sang and played the lyre for the rowdy crowd of suitors in the house of Odysseus? ________________________________________________________________________ -

University of Cincinnati

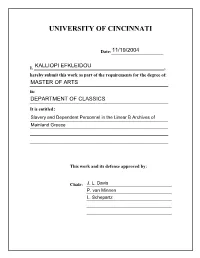

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ SLAVERY AND DEPENDENT PERSONNEL IN THE LINEAR B ARCHIVES OF MAINLAND GREECE A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Classical Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences 2004 by Kalliopi Efkleidou B.A., Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 2001 Committee Chair: Jack L. Davis ABSTRACT SLAVERY AND DEPENDENT PERSONNEL IN THE LINEAR B ARCHIVES OF MAINLAND GREECE by Kalliopi Efkleidou This work focuses on the relations of dominance as they are demonstrated in the Linear B archives of Mainland Greece (Pylos, Tiryns, Mycenae, and Thebes) and discusses whether the social status of the “slave” can be ascribed to any social group or individual. The analysis of the Linear B tablets demonstrates that, among the lower-status people, a social group that has been generally treated by scholars as internally undifferentiated, there were differentiations in social status and levels of dependence. A set of conditions that have been recognized as being of central importance to the description of the -

Defining Orphism: the Beliefs, the Teletae and the Writings

Defining Orphism: the Beliefs, the teletae and the Writings Anthi Chrysanthou Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Languages, Cultures and Societies Department of Classics May 2017 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his/her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. I This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2017 The University of Leeds and Anthi Chrysanthou. The right of Anthi Chrysanthou to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. II Acknowledgements This research would not have been possible without the help and support of my supervisors, family and friends. Firstly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisors Prof. Malcolm Heath and Dr. Emma Stafford for their constant support during my research, for motivating me and for their patience in reading my drafts numerous times. It is due to their insightful comments and constructive feedback that I have managed to evolve as a researcher and a person. Our meetings were always delightful and thought provoking. I could not have imagined having better mentors for my Ph.D studies. Special thanks goes to Prof. Malcolm Heath for his help and advice on the reconstruction of the Orphic Rhapsodies. I would also like to thank the University of Leeds for giving me the opportunity to undertake this research and all the departmental and library staff for their support and guidance. -

For a Falcon

New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Introduction by Robert Graves CRESCENT BOOKS NEW YORK New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Translated by Richard Aldington and Delano Ames and revised by a panel of editorial advisers from the Larousse Mvthologie Generate edited by Felix Guirand and first published in France by Auge, Gillon, Hollier-Larousse, Moreau et Cie, the Librairie Larousse, Paris This 1987 edition published by Crescent Books, distributed by: Crown Publishers, Inc., 225 Park Avenue South New York, New York 10003 Copyright 1959 The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited New edition 1968 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the permission of The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. ISBN 0-517-00404-6 Printed in Yugoslavia Scan begun 20 November 2001 Ended (at this point Goddess knows when) LaRousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Introduction by Robert Graves Perseus and Medusa With Athene's assistance, the hero has just slain the Gorgon Medusa with a bronze harpe, or curved sword given him by Hermes and now, seated on the back of Pegasus who has just sprung from her bleeding neck and holding her decapitated head in his right hand, he turns watch her two sisters who are persuing him in fury. Beneath him kneels the headless body of the Gorgon with her arms and golden wings outstretched. From her neck emerges Chrysor, father of the monster Geryon. Perseus later presented the Gorgon's head to Athene who placed it on Her shield. -

The Iliad of Homer by Homer

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Iliad of Homer by Homer This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Iliad of Homer Author: Homer Release Date: September 2006 [Ebook 6130] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ILIAD OF HOMER*** The Iliad of Homer Translated by Alexander Pope, with notes by the Rev. Theodore Alois Buckley, M.A., F.S.A. and Flaxman's Designs. 1899 Contents INTRODUCTION. ix POPE'S PREFACE TO THE ILIAD OF HOMER . xlv BOOK I. .3 BOOK II. 41 BOOK III. 85 BOOK IV. 111 BOOK V. 137 BOOK VI. 181 BOOK VII. 209 BOOK VIII. 233 BOOK IX. 261 BOOK X. 295 BOOK XI. 319 BOOK XII. 355 BOOK XIII. 377 BOOK XIV. 415 BOOK XV. 441 BOOK XVI. 473 BOOK XVII. 513 BOOK XVIII. 545 BOOK XIX. 575 BOOK XX. 593 BOOK XXI. 615 BOOK XXII. 641 BOOK XXIII. 667 BOOK XXIV. 707 CONCLUDING NOTE. 747 Illustrations HOMER INVOKING THE MUSE. .6 MARS. 13 MINERVA REPRESSING THE FURY OF ACHILLES. 16 THE DEPARTURE OF BRISEIS FROM THE TENT OF ACHILLES. 23 THETIS CALLING BRIAREUS TO THE ASSISTANCE OF JUPITER. 27 THETIS ENTREATING JUPITER TO HONOUR ACHILLES. 32 VULCAN. 35 JUPITER. 38 THE APOTHEOSIS OF HOMER. 39 JUPITER SENDING THE EVIL DREAM TO AGAMEMNON. 43 NEPTUNE. 66 VENUS, DISGUISED, INVITING HELEN TO THE CHAMBER OF PARIS. -

The Festival Proerosia Robertson, Noel Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1996; 37, 4; Proquest Pg

New Light on Demeter's Mysteries: The Festival Proerosia Robertson, Noel Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1996; 37, 4; ProQuest pg. 319 New Light on Demeter's Mysteries: The Festival Proerosia Noel Robertson EMETER'S "MYSTERIES: festivals conducted mainly by women and in sanctuaries that were suitably withdrawn, D were almost universal in Greek cities, like the cereal agri culture they were intended to promote. They were integral to Greek society and are now widely and profitably studied as a social phenomenon. If the general custom is important, so are the many ritual actions that constitute a given festival, through which (according to one's point of view) the women either worship the goddess Demeter, or work directly on the earth, or affirm their sense of the fitness of things. Animal sacrifice plays a large part, as usual, the pig species being favored by De meter, and there is a peculiar practice of throwing piglets into a pit, which is then closed. It is a disadvantage that reconstructions of ritual must be sought in older handbooks and special studies. The basic work on Greek festivals was done long ago, and new evidence, though not wholly neglected, has not led to any sustained effort of revision. The festival Proerosia, "Before-ploughing (rites)," is such a case. The Athenian, or Eleusinian, version of this festival once seemed to stand alone, as if it were something secondary and contrived, without much bearing on the larger pattern of Demeter's worship. We can now see that the Proerosia was widespread. It may have been as common as the greatest of Demeter's festivals, the Thesmophoria: it was a sequel to it, coming later in the autumn season.