Papua New Guinea Fly Estuary ^ ^ S O U T H W E S T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APLL Conference Abstracts

13th International Austronesian and Papuan Languages and Linguistics Conference (APLL13) https://www.ed.ac.uk/ppls/linguistics-and-english-language/events/apll13-2021-06-10 The purpose of the APLL conferences is to provide a venue for presentation of the best current research on Austronesian and Papuan languages and linguistics, and to promote collaboration and research in this area. APLL13 follows a successful online instantiation of APLL, hosted by the University of Oslo, as well as previous APLL conferences held in Leiden, Surrey, Paris and London, and the Austronesian Languages and Linguistics (ALL) conferences held at SOAS and St Catherine's College, Oxford. Language and Culture Research Centre (James Cook University) representative Robert Bradshaw gave a Poster presentation on ‘Frustrative in Doromu-Koki’ (LINK TO POSTER) Additionally, LCRC Associates Dr René van den Berg (SIL International) gave a talk on ‘Un- Austronesian features of Malol, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea’ Dr Hannah Sarvasy presented ‘Nungon Switch-Reference: Processing and Acquisition’ and Dr Dineke Schokkin, University of Canterbury in association with Kate L. Lindsey, Boston University presented ‘A new type of auxiliary: Evidence from Pahoturi River complex predicates’ Abstracts of those sessions are presented below Frustrative in Doromu-Koki Robert L. Bradshaw Language and Culture Research Centre – James Cook University The category of frustrative, defined as ‘…a grammatical marker that expresses the nonrealization of some expected outcome implied by the proposition expressed in the marked clause (Overall 2017:479)’, has been identified in a few languages of the world, including those of Amazonia. A frustrative, translated as ‘in vain’, typically expresses an unrealised expectation and lack of accomplishment, as well as negative evaluation. -

Papua New Guinea

PAPUA NEW GUINEA EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS OPERATIONAL LOGISTICS CONTINGENCY PLAN PART 2 –EXISTING RESPONSE CAPACITY & OVERVIEW OF LOGISTICS SITUATION GLOBAL LOGISTICS CLUSTER – WFP FEBRUARY – MARCH 2011 1 | P a g e A. Summary A. SUMMARY 2 B. EXISTING RESPONSE CAPACITIES 4 C. LOGISTICS ACTORS 6 A. THE LOGISTICS COORDINATION GROUP 6 B. PAPUA NEW GUINEAN ACTORS 6 AT NATIONAL LEVEL 6 AT PROVINCIAL LEVEL 9 C. INTERNATIONAL COORDINATION BODIES 10 DMT 10 THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL 10 D. OVERVIEW OF LOGISTICS INFRASTRUCTURE, SERVICES & STOCKS 11 A. LOGISTICS INFRASTRUCTURES OF PNG 11 PORTS 11 AIRPORTS 14 ROADS 15 WATERWAYS 17 STORAGE 18 MILLING CAPACITIES 19 B. LOGISTICS SERVICES OF PNG 20 GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS 20 FUEL SUPPLY 20 TRANSPORTERS 21 HEAVY HANDLING AND POWER EQUIPMENT 21 POWER SUPPLY 21 TELECOMS 22 LOCAL SUPPLIES MARKETS 22 C. CUSTOMS CLEARANCE 23 IMPORT CLEARANCE PROCEDURES 23 TAX EXEMPTION PROCESS 24 THE IMPORTING PROCESS FOR EXEMPTIONS 25 D. REGULATORY DEPARTMENTS 26 CASA 26 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH 26 NATIONAL INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGY AUTHORITY (NICTA) 27 2 | P a g e MARITIME AUTHORITIES 28 1. NATIONAL MARITIME SAFETY AUTHORITY 28 2. TECHNICAL DEPARTMENTS DEPENDING FROM THE NATIONAL PORT CORPORATION LTD 30 E. PNG GLOBAL LOGISTICS CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS 34 A. CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS PROPOSED 34 MAJOR PROBLEMS/BOTTLENECKS IDENTIFIED: 34 SOLUTIONS PROPOSED 34 B. EXISTING OPERATIONAL CORRIDORS IN PNG 35 MAIN ENTRY POINTS: 35 SECONDARY ENTRY POINTS: 35 EXISTING CORRIDORS: 36 LOGISTICS HUBS: 39 C. STORAGE: 41 CURRENT SITUATION: 41 PROPOSED LONG TERM SOLUTION 41 DURING EMERGENCIES 41 D. DELIVERIES: 41 3 | P a g e B. Existing response capacities Here under is an updated list of the main response capacities currently present in the country. -

Submission No. 7 (Pacific Health) If

Submission No. 7 (Pacific Health) if Submission to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health and Ageing on Western Province Torres Strait: Cross Border Health Issues PURPOSE To propose a long term systemic approach to addressing health issues in Western province to reduce risks and impacts of cross border health issues on the health and well-being of Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal people of the Torres Strait region. KEY POINTS The major health risks in the border area include: » Tuberculosis, including multi-drug resistant TB; • Sexually transmitted infections and HIV and AIDS; « Vector borne disease including malaria, Japanese Encephalitis and Dengue; • Immunisable diseases; and, • Avian Influenza. There is no short term "quick fix" for the health services in Western Province. A long term perspective must be taken. The level of resources to control the health issues of concern cannot be underestimated and will require a "whole of system" approach. Specifically the major challenges are: • There is no stable well functioning health centre in the Treaty Area and difficulties remain in retaining health staff in these areas; • TB is a growing problem and no major program of activity is schedule till 2010. Multi-drug resistant TB is an emerging problem in this area; « Malaria Bed Net Distribution Programs have stalled; • There are high reported rates of STIs and HIV and limited control programs; • The PNG government drugs and supply program does not ensure deliveries of essential drugs to the province; • There is no -

Ports of New Guinea Revisited (A Trip Down Memory Lane)

Ports of New Guinea Revisited (A Trip Down Memory Lane) Not named the “Paradise Islands” without due reason. Papua New Guinea and its outlaying islands must rank amongst the top in the global scale of beauty for both Fauna and Flora, not to mention the pristine Aquatic attributes these islands possess. If crystal blue water, silver sandy beaches, swaying palms, coral reefs, lush tropical rainforest, reptiles, and birds together with a country steeped in history and culture stokes your imagination, then this should become your choice of destination. It is true that Papua New Guinea is not blessed with an extensive infrastructure of highways and good roads and the only realistic way to explore these islands is by light aircraft, or better still, by ship. I spent a memorable 4-5 years of my sea-going career in the Pacific Islands, including New Guinea, and it is based on my observations and experiences that this narration is derived. During the 1970s and early 80s I was fortunate to have the opportunity to sail around these waters in my capacity as a professional seafarer. It covered a relatively short period, but it was a time of great adventure and feeling of exploration, bearing in mind that during those years New Guinea was completely unspoiled by the influences of Western society and retained much more mystique and feeling of the “unknown” compared to today. What follows is a personal recap and description, of what I can remember of those years I spent in the region. Map showing main Ports of New Guinea DARU Island - this is a small elliptical island close to the mainland in the western region of Papua New Guinea. -

A Taxono1vhc Revision of the Genus Faradaya F. Muell

J. Adelaide Bot. Gard 10(2): 165-177 (1987) A TAXONO1VHC REVISION OF THE GENUS FARADAYA F. MUELL. (VERBENACEAE)* IN AUSTRALIA Ahmad Abid Munir State Herbarium, Botanic Gardens, North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia 5000 Abstract A taxonomic revision of Faradaya in Australia is presented. The following two species are recognised: F. albertisii and E splendida. F. albertisii is confirmed from Australia. A wide range of material has been examined from Malesia and Oceania. The affinities and distribution are considered for the genus and each species. A key to the species is provided and a detailed description of each species is supplemented by an illustration. Taxonomic History of the Genus The genus Faradaya was described by F. Mueller (1865) with one species, E splendida, the type of which came from Queensland. Originally it was placed in the Bignoniaceae, but soon after its publication, Seemann (1865) referred the genus to the "Natural Order Verbenaceae, closely related to Clerodendrum and Oxera". The family Verbenaceae has been accepted for the genus by all subsequent botanists. Earlier, one Faradaya collection from Tonga and another from Fiji were respectively described by Seemann (1862) and Asa Gray (1862) as new species of Clerodendrum. In view of their difference from other Clerodendrum taxa, Asa Gray (1862) formed for them a new section of the genus namely Clerodendrum sect. Tetrathyranthus A. Gray. Subsequently, Seemann (1865) recognised both types of the section Tetrathyranthus as Faradaya species and thus reduced this section to synonymy under Faradaya. Bentham (1870, 1876) divided the family Verbenaceae into different tribes, with Faradaya in the tribe Viticeae subtribe Oxereae. -

OK-FLY SOCIAL MONITORING PROJECT REPORT No

LOWER FLY AREA STUDY “You can’t buy another life from a store” OK-FLY SOCIAL MONITORING PROJECT REPORT No. 9 for Ok Tedi Mining Limited Original publication details: Reprint publication details: David Lawrence David Lawrence North Australia Research Unit Resource Management in Asia-Pacific Program Lot 8688 Ellengowan Drive Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies Brinkin NT 0810 Australian National University ACT 0200 Australia John Burton (editor) Pacific Social Mapping John Burton (editor) 49 Wentworth Avenue Resource Management in Asia-Pacific Program CANBERRA ACT 2604 Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies Australia Australian National University ACT 0200 Australia Unisearch PNG Pty Ltd Box 320 UNIVERSITY NCD Papua New Guinea May 1995 reprinted October 2004 EDITOR’S PREFACE This volume is the ninth in a series of reports for the Ok-Fly Social Monitoring Project. Colin Filer’s Baseline documentation. OFSMP Report No. 1 and my own The Ningerum LGC area. OFSMP Report No. 2, appeared in 1991. My Advance report summary for Ningerum-Awin area study. OFSMP Report No. 3, David King’s Statistical geography of the Fly River Development Trust. OFSMP Report No. 4, and the two major studies from the 1992 fieldwork, Stuart Kirsch’s The Yonggom people of the Ok Tedi and Moian Census Divisions: an area study. OFSMP Report No. 5 and my Development in the North Fly and Ningerum-Awin area study. OFSMP Report No. 6, were completed in 1993. I gave a precis of our findings to 1993 in Social monitoring at the Ok Tedi project. Summary report to mid- 1993. -

Abstract of Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania

Abstract of http://www.uog.ac.pg/glec/thesis/ch1web/ABSTRACT.htm Abstract of Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania by Glendon A. Lean In modern technological societies we take the existence of numbers and the act of counting for granted: they occur in most everyday activities. They are regarded as being sufficiently important to warrant their occupying a substantial part of the primary school curriculum. Most of us, however, would find it difficult to answer with any authority several basic questions about number and counting. For example, how and when did numbers arise in human cultures: are they relatively recent inventions or are they an ancient feature of language? Is counting an important part of all cultures or only of some? Do all cultures count in essentially the same ways? In English, for example, we use what is known as a base 10 counting system and this is true of other European languages. Indeed our view of counting and number tends to be very much a Eurocentric one and yet the large majority the languages spoken in the world - about 4500 - are not European in nature but are the languages of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific, Africa, and the Americas. If we take these into account we obtain a quite different picture of counting systems from that of the Eurocentric view. This study, which attempts to answer these questions, is the culmination of more than twenty years on the counting systems of the indigenous and largely unwritten languages of the Pacific region and it involved extensive fieldwork as well as the consultation of published and rare unpublished sources. -

A Grammar of Komnzo

A grammar of Komnzo Christian Döhler language Studies in Diversity Linguistics 22 science press Studies in Diversity Linguistics Editor: Martin Haspelmath In this series: 1. Handschuh, Corinna. A typology of marked-S languages. 2. Rießler, Michael. Adjective attribution. 3. Klamer, Marian (ed.). The Alor-Pantar languages: History and typology. 4. Berghäll, Liisa. A grammar of Mauwake (Papua New Guinea). 5. Wilbur, Joshua. A grammar of Pite Saami. 6. Dahl, Östen. Grammaticalization in the North: Noun phrase morphosyntax in Scandinavian vernaculars. 7. Schackow, Diana. A grammar of Yakkha. 8. Liljegren, Henrik. A grammar of Palula. 9. Shimelman, Aviva. A grammar of Yauyos Quechua. 10. Rudin, Catherine & Bryan James Gordon (eds.). Advances in the study of Siouan languages and linguistics. 11. Kluge, Angela. A grammar of Papuan Malay. 12. Kieviet, Paulus. A grammar of Rapa Nui. 13. Michaud, Alexis. Tone in Yongning Na: Lexical tones and morphotonology. 14. Enfield, N. J. (ed.). Dependencies in language: On the causal ontology of linguistic systems. 15. Gutman, Ariel. Attributive constructions in North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic. 16. Bisang, Walter & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios. 17. Stenzel, Kristine & Bruna Franchetto (eds.). On this and other worlds: Voices from Amazonia. 18. Paggio, Patrizia and Albert Gatt (eds.). The languages of Malta. 19. Seržant, Ilja A. & Alena Witzlack-Makarevich (eds.). Diachrony of differential argument marking. 20. Hölzl, Andreas. A typology of questions in Northeast Asia and beyond: An ecological perspective. 21. Riesberg, Sonja, Asako Shiohara & Atsuko Utsumi (eds.). Perspectives on information structure in Austronesian languages. 22. Döhler, Christian. A grammar of Komnzo. ISSN: 2363-5568 A grammar of Komnzo Christian Döhler language science press Döhler, Christian. -

A Trial Separation: Australia and the Decolonisation of Papua New Guinea

A TRIAL SEPARATION A TRIAL SEPARATION Australia and the Decolonisation of Papua New Guinea DONALD DENOON Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Denoon, Donald. Title: A trial separation : Australia and the decolonisation of Papua New Guinea / Donald Denoon. ISBN: 9781921862915 (pbk.) 9781921862922 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Decolonization--Papua New Guinea. Papua New Guinea--Politics and government Dewey Number: 325.953 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover: Barbara Brash, Red Bird of Paradise, Print Printed by Griffin Press First published by Pandanus Books, 2005 This edition © 2012 ANU E Press For the many students who taught me so much about Papua New Guinea, and for Christina Goode, John Greenwell and Alan Kerr, who explained so much about Australia. vi ST MATTHIAS MANUS GROUP MANUS I BIS MARCK ARCH IPEL AGO WEST SEPIK Wewak EAST SSEPIKEPIK River Sepik MADANG NEW GUINEA ENGA W.H. Mt Hagen M Goroka a INDONESIA S.H. rk ha E.H. m R Lae WEST MOROBEMOR PAPUA NEW BRITAIN WESTERN F ly Ri ver GULF NORTHERNOR N Gulf of Papua Daru Port Torres Strait Moresby CENTRAL AUSTRALIA CORAL SEA Map 1: The provinces of Papua New Guinea vii 0 300 kilometres 0 150 miles NEW IRELAND PACIFIC OCEAN NEW IRELAND Rabaul BOUGAINVILLE I EAST Arawa NEW BRITAIN Panguna SOLOMON SEA SOLOMON ISLANDS D ’EN N TR E C A S T E A U X MILNE BAY I S LOUISIADE ARCHIPELAGO © Carto ANU 05-031 viii W ALLAC E'S LINE SUNDALAND WALLACEA SAHULLAND 0 500 km © Carto ANU 05-031b Map 2: The prehistoric continent of Sahul consisted of the continent of Australia and the islands of New Guinea and Tasmania. -

0=AFRICAN Geosector

2= AUSTRALASIA geosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 123 2=AUSTRALASIA geosector édition princeps foundation edition DU RÉPERTOIRE DE LA LINGUASPHÈRE 1999-2000 THE LINGUASPHERE REGISTER 1999-2000 publiée en ligne et mise à jour dès novembre 2012 published online & updated from November 2012 This geosector covers 223 sets of languages (1167 outer languages, composed of 2258 inner languages) spoken or formerly spoken by communities in Australasia in a geographic sequence from Maluku and the Lesser Sunda islands through New Guinea and its adjacent islands, and throughout the Australian mainland to Tasmania. They comprise all languages of Australasia (Oceania) not covered by phylosectors 3=Austronesian or 5=Indo-European. Zones 20= to 24= cover all so-called "Papuan" languages, spoken on Maluku and the Lesser Sunda islands and the New Guinea mainland, which have been previously treated within the "Trans-New Guinea" hypothesis: 20= ARAFURA geozone 21= MAMBERAMO geozone 22= MANDANGIC phylozone 23= OWALAMIC phylozone 24= TRANSIRIANIC phylozone Zones 25= to 27= cover all other so-called "Papuan" languages, on the New Guinea mainland, Bismarck archipelago, New Britain, New Ireland and Solomon islands, which have not been treated within the "Trans-New Guinea" hypothesis: 25= CENDRAWASIH geozone 26= SEPIK-VALLEY geozone 27= BISMARCK-SEA geozone Zones 28= to 29= cover all languages spoken traditionally across the Australian mainland, on the offshore Elcho, Howard, Crocodile and Torres Strait islands (excluding Darnley island), and formerly on the island of Tasmania. An "Australian" hypothesis covers all these languages, excluding the extinct and little known languages of Tasmania, comprising (1.) an area of more diffuse and complex relationships in the extreme north, covered here by geozone 28=, and (2.) a more closely related affinity (Pama+ Nyungan) throughout the rest of Australia, covered by 24 of the 25 sets of phylozone 29=. -

99. the Agiba Cult of the Kerewa Culture Author(S): A

99. The Agiba Cult of the Kerewa Culture Author(s): A. C. Haddon Source: Man, Vol. 18 (Dec., 1918), pp. 177-183 Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2788511 Accessed: 26-06-2016 05:21 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Man This content downloaded from 128.110.184.42 on Sun, 26 Jun 2016 05:21:30 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Dec., 1918.] MAN. [No. 99. ORIGINAL ARTIOLES. With Plate M. Gulf of Papua: Ethnography. Haddon. The Agiba Cult of the Kerewa Culture. By A. C. Haddon. n_ In the Gulf of Papua there may be distinguished foiir cultures, UU which, from east to west, may be termed the Elema, the Namau, the Urama, and the Kerewa; of these the three first are distinctly inter-related, but the last is more distinct. Without doubt these cultures have reached the coast from the interior of the island, though we are as yet ignorant of the routes they have traversed. -

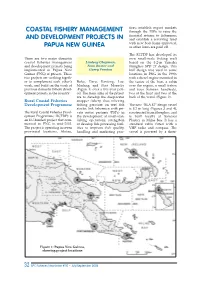

Coastal Fishery Management and Development Projects in Papua

tices; establish export markets COASTAL FISHERY MANAGEMENT through the PSPs to raise the financial returns to fishermen; AND DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS IN and establish a revolving fund with new boat loans approved, PAPUA NEW GUINEA as other loans are paid off. The RCFDP has developed its There are two major domestic own small-scale fishing craft coastal fisheries management Lindsay Chapman, based on the 8.2-m Yamaha and development projects being Sean Baxter and fibreglass SPD 27 design. This implemented in Papua New Garry Preston hull design was used in some Guinea (PNG) at present. These locations in PNG in the 1990s two projects are working togeth- with a diesel engine mounted in er to complement each other’s Buka, Daru, Kavieng, Lae, the centre of the boat, a cabin work, and build on the work of Madang and Port Moresby over the engine, a small icebox previous domestic fishery devel- (Figure 1) over a five-year peri- and four Samoan handreels, opment projects in the country. od. The main aims of the project two at the front and two at the are to develop the deep-water back of the vessel (Figure 2). Rural Coastal Fisheries snapper fishery, thus relieving Development Programme fishing pressure on reef fish The new “ELA 82” design vessel stocks; link fishermen with pri- is 8.2 m long (Figures 3 and 4), The Rural Coastal Fisheries Devel- vate sector partners (PSPs) in constructed from fibreglass, and opment Programme (RCFDP) is the development of small-scale is built locally at Samarai an EU-funded project that com- fishing operations; strengthen Plastics in Milne Bay.