Displacement and the Vulnerability to Mobilize for Violence EVIDENCE from AFGHANISTAN by Sadaf Lakhani and Rahmatullah Amiri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

AFGHANISTAN - Base Map KYRGYZSTAN

AFGHANISTAN - Base map KYRGYZSTAN CHINA ± UZBEKISTAN Darwaz !( !( Darwaz-e-balla Shaki !( Kof Ab !( Khwahan TAJIKISTAN !( Yangi Shighnan Khamyab Yawan!( !( !( Shor Khwaja Qala !( TURKMENISTAN Qarqin !( Chah Ab !( Kohestan !( Tepa Bahwddin!( !( !( Emam !( Shahr-e-buzorg Hayratan Darqad Yaftal-e-sufla!( !( !( !( Saheb Mingajik Mardyan Dawlat !( Dasht-e-archi!( Faiz Abad Andkhoy Kaldar !( !( Argo !( Qaram (1) (1) Abad Qala-e-zal Khwaja Ghar !( Rostaq !( Khash Aryan!( (1) (2)!( !( !( Fayz !( (1) !( !( !( Wakhan !( Khan-e-char Char !( Baharak (1) !( LEGEND Qol!( !( !( Jorm !( Bagh Khanaqa !( Abad Bulak Char Baharak Kishim!( !( Teer Qorghan !( Aqcha!( !( Taloqan !( Khwaja Balkh!( !( Mazar-e-sharif Darah !( BADAKHSHAN Garan Eshkashem )"" !( Kunduz!( !( Capital Do Koh Deh !(Dadi !( !( Baba Yadgar Khulm !( !( Kalafgan !( Shiberghan KUNDUZ Ali Khan Bangi Chal!( Zebak Marmol !( !( Farkhar Yamgan !( Admin 1 capital BALKH Hazrat-e-!( Abad (2) !( Abad (2) !( !( Shirin !( !( Dowlatabad !( Sholgareh!( Char Sultan !( !( TAKHAR Mir Kan Admin 2 capital Tagab !( Sar-e-pul Kent Samangan (aybak) Burka Khwaja!( Dahi Warsaj Tawakuli Keshendeh (1) Baghlan-e-jadid !( !( !( Koran Wa International boundary Sabzposh !( Sozma !( Yahya Mussa !( Sayad !( !( Nahrin !( Monjan !( !( Awlad Darah Khuram Wa Sarbagh !( !( Jammu Kashmir Almar Maymana Qala Zari !( Pul-e- Khumri !( Murad Shahr !( !( (darz !( Sang(san)charak!( !( !( Suf-e- (2) !( Dahana-e-ghory Khowst Wa Fereng !( !( Ab) Gosfandi Way Payin Deh Line of control Ghormach Bil Kohestanat BAGHLAN Bala !( Qaysar !( Balaq -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

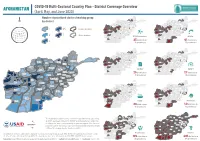

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of Prioritized Clusters/Working Group

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of prioritized clusters/working group Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh N by district Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar 1 4-5 province boundary Logar Logar Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Paktya Paktya Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika 2 7 district boundary Zabul Zabul DTM Prioritized: WASH: Hilmand Hilmand Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz 25 districts in 41 districts in 3 10 provinces 13 provinces Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Badakhshan Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar Jawzjan Logar Logar Kunduz Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Balkh Paktya Paktya Takhar Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika Faryab Zabul Zabul Samangan Baghlan Hilmand EiEWG: Hilmand ESNFI: Sar-e-Pul Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz Panjsher Nuristan 25 districts in 27 districts in Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar 10 provinces 12 provinces Laghman Kabul Maidan -

Afghanistan Ghazni Province Land Cover

W # AFGHANISTAN E C Sar-e K har Dew#lak A N # GHAZNI PROVINCE Qarah Qowl( 1) I Qarkh Kamarak # # # # # Regak # # Gowshak # # # Qarah Qowl( 2) R V Qada # # # # # # Bandsang # # Dopushta Panqash # # # # # # # Qashkoh Kholaqol # LAND COVER MAP # Faqir an O # Sang Qowl Rahim Dad # # Diktur (1) # Owr Mordah Dahane Barikak D # Barigah # # # Sare Jiska # Baday # # Kheyr Khaneh # Uchak # R # Jandad # # # # # # # # # # Shakhalkhar Zardargin Bumak # # Takhuni # # # # # # # Karez Nazar # Ambolagh # # # # # # Barikak # # Hesar # # # # # Yarum # # # A P # # # # # # Kataqal'a Kormurda # # # # Qeshlaqha Riga Jusha Tar Bulagh # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # Ahangari # # Kuz Foladay # Minqol # # # Syahreg (2) # # # Maqa # Sanginak # # Baghalak # # # # # # # # # Sangband # Orka B aba # Godowl # Nayak # # # Gadagak # # # # Kota Khwab Altan # # Bahram # # # Katar # # # Barik # Qafak # Qargatak # # # # # # Garmak (3) # # # # # # # # # # Ternawa # # # Kadul # # # # Ghwach # K # # Ata # # # Dandab # # # # # Qole Khugan Sewak (2) Sorkh Dival # # # # # # # # Qabzar (2) # # Bandali # Ajar # Shebar # Hajegak # Sawzsang Podina N ## # # Churka # Nala # # # # # # # Qabzar-1 Turgha # Tughni # Warzang Sultani # # # # # # # # # # # # # Ramzi Qureh Now Juy Negah # # # # # # # # Shew Qowl # Syahsangak A # # # # # # # O # Diktur (2) # Kajak # # Mar Bolagh R V # Ajeda # Gola Karizak # # # Navor Sham # # Dahane Yakhshi Kolukh P # # # # AIMS Y Tanakhak Qal'a-i Dasht I Qole Aymad # Kotal Olsenak Mianah Bed # # # # N Tarbolagh Mar qolak Minqolak Sare Bed Sare Kor ya Ta`ina -

Local Perspectives on Peace and Elections Ghazni Province, South-Eastern Afghanistan

Local perspectives on peace and elections Ghazni Province, south-eastern Afghanistan Interviews conducted by Abdul Hadi Sadat, a researcher with Unit (AREU), the Center for Policy and Human Development over 15 years of experience in qualitative social research with (CPHD) and Creative Associates International. He has a degree organisations including the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation injournalism from Kabul University. ABSTRACT The following statements are taken from longer their views on elections, peace and reconciliation. interviews with community members across two Respondents’ ages and ethnic groups vary, as do their different rural districts in Ghazni Province in south- levels of literacy. Data were collected by Abdul Hadi eastern Afghanistan between November 2017 and Sadat as part of a larger research project funded by the March 2018. Interviewees were asked questions about UK’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Female NGO employee I think the international organisations’ involvement is very Government officials and the IEC [Independent Election vital and they have an important role in elections, but I Commission] are not capable of talking with the Taliban don’t think they will have an important role in reconciliation regarding the election, but community representatives can with the Taliban because they themselves do not want convince them not to do anything to disrupt the election and Afghanistan to be in peace. If they wanted this we would even encourage them to participate in the election process. have better life. They have the power to force the Taliban to reconcile with Afghanistan government. Female youth, unemployed I don’t know for sure whether the Taliban will allow elections Male village elder to take place here or not, but in those villages where the For decades we have been experiencing war so all people security is low the Taliban will not let the people go to the are very tired with fighting, killing and bombing. -

AFGHANISTAN MAP Central Region

Chal #S Aliabad #S BALKH Char Kent Hazrat- e Sultan #S AFGHANISTAN MAP #S Qazi Boi Qala #S Ishkamesh #S Baba Ewaz #S Central Region #S Aibak Sar -e Pul Islam Qala Y# Bur ka #S #S #S Y# Keshendeh ( Aq Kopruk) Baghlan-e Jadeed #S Bashi Qala Du Abi #S Darzab #S #S Dehi Pul-e Khumri Afghan Kot # #S Dahana- e Ghori #S HIC/ProMIS Y#S Tukzar #S wana Khana #S #S SAMANGAN Maimana Pasni BAGHLAN Sar chakan #S #S FARYAB Banu Doshi Khinjan #S LEGEND SARI PUL Ruy-e Du Ab Northern R#S egion#S Tarkhoj #S #S Zenya BOUNDARIES Qala Bazare Tala #S #S #S International Kiraman Du Ab Mikh Zar in Rokha #S #S Province #S Paja Saighan #S #S Ezat Khel Sufla Haji Khel District Eshqabad #S #S Qaq Shal #S Siyagerd #S UN Regions Bagram Nijrab Saqa #S Y# Y# Mahmud-e Raqi Bamyan #S #S #S Shibar Alasai Tagab PASaRlahWzada AN CharikarQara Bagh Mullah Mohd Khel #S #S Istalif CENTERS #S #S #S #S #S Y# Kalakan %[ Capital Yakawlang #S KAPISA #S #S Shakar Dara Mir Bacha Kot #S Y# Province Sor ubi Par k- e Jamhuriat Tara Khel BAMYAN #S #S Kabul#S #S Lal o Sar Jangal Zar Kharid M District Tajikha Deh Qazi Hussain Khel Y# #S #S Kota-e Ashro %[ Central Region #S #S #S KABUL #S ROADS Khord Kabul Panjab Khan-e Ezat Behsud Y# #S #S Chaghcharan #S Maidan Shar #S All weather Primary #S Ragha Qala- e Naim WARDAK #S Waras Miran Muhammad Agha All weather Secondary #S #S #S Azro LOGAR #S Track East Chake-e Wnar dtark al RegiKolangar GHOR #S #S RIVERS Khoshi Sayyidabad Bar aki Bar ak #S # #S Ali Khel Khadir #S Y Du Abi Main #S #S Gh #S Pul-e Alam Western Region Kalan Deh Qala- e Amr uddin -

Ethnicity, Space, and Politics in Afghanistan

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Urban Studies Senior Seminar Papers Urban Studies Program 11-2009 Ethnicity, Space, and Politics in Afghanistan Benjamin Dubow University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/senior_seminar Dubow, Benjamin, "Ethnicity, Space, and Politics in Afghanistan" (2009). Urban Studies Senior Seminar Papers. 13. https://repository.upenn.edu/senior_seminar/13 Suggested Citation: Benjamin Dubow. "Ethnicity, Space, and Politics in Afghanistan." University of Pennsylvania, Urban Studies Program. 2009. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/senior_seminar/13 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ethnicity, Space, and Politics in Afghanistan Abstract The 2004 election was a disaster. For all the unity that could have come from 2001, the election results shattered any hope that the country had overcome its fractures. The winner needed to find a way to unite a country that could not be more divided. In Afghanistan’s Panjshir Province, runner-up Yunis Qanooni received 95.0% of the vote. In Paktia Province, incumbent Hamid Karzai received 95.9%. Those were only two of the seven provinces where more than 90% or more of the vote went to a single candidate. Two minor candidates who received less than a tenth of the total won 83% and 78% of the vote in their home provinces. For comparison, the most lopsided state in the 2004 United States was Wyoming, with 69% of the vote going to Bush. This means Wyoming voters were 1.8 times as likely to vote for Bush as were Massachusetts voters. Paktia voters were 120 times as likely to vote for Karzai as were Panjshir voters. -

Caring for Their Own: a Stronger Afghan Response to Civilian Harm

Part of the Countries in Conflict Series Caring for Their Own: A Stronger Afghan Response to Civilian Harm CARING FOR THEIR OWN: A STRONGER AFGHAN RESPONSE TO CIVILIAN HARM Acknowledgements Center for Civilians in Conflict would like to thank Open Society Foundations (OSF), which provided funding to support this research and offered insightful comments during the drafting of this report. We also appreciate the Afghan translators and interpreters that worked diligently to deliver quality research for this report, as well as those that offered us travel assistance. Finally, Center for Civilians in Conflict is deeply grateful to all those interviewed for this report, especially civilians suffering from the con- flict in Afghanistan, for their willingness to share their stories, experi- ences and views with us. Copyright © 2013 Center for Civilians in Conflict (formerly CIVIC) All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America. Copies of this report are available for download at: www.civiliansinconflict.org NOTE: Many names in this report have been changed to protect the identity of those interviewed. Cover photo courtesy of James Longley. All photos in text by Trevor Keck/Center for Civilians in Conflict. Map of Afghanistan C A m H 64 u 66 68 70 72 Mur 74 H ° D ° ° ° a-ye ° gho ° ar y b INA ya UZBEKISTAN r INA a AFGHANISTAN D Qurghonteppa TAJIKISTAN Kerki (Kurgan-Tyube) Mary Kiroya iz M rm Dusti Khorugh u e BADAKHSHAN r T g a Keleft Rostaq FayzFayzabad Abad b ir Qala-I-Panjeh Andkhvoy Jeyretan am JAWZJAN P Mazar-e-Sharif KUNDUZ -

AFGHANISTAN: Poverty in Provinces (Provincial Briefs, NRVA 2007/08)

AFGHANISTAN: Poverty in Provinces (Provincial Briefs, NRVA 2007/08) Proportion of population whose per-capita consumption is below the poverty line Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Takhar Badakhshan Samangan Faryab Baghlan Sari Pul Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Bamyan Parwan Kapisa Kunar Poverty Measures Laghman Ghor Maydan Kabul The headcount rate or poverty incidence or poverty rate is the proportion of Hirat Wardak Nangarhar population whose per-capita consumption is below the poverty line i.e. the Logar Poverty Rate poverty threshold of 1,255 Afs (approximately 25 USD) monthly consumption Daykundi 9 - 10 expenditure representing the typical cost of attaining 2,100 calories per person Paktya Ghazni Khost 11 - 20 per day and of meeting some basic non-food needs. 21 - 30 Uruzgan The poverty line or poverty threshold is the minimum level of per-capita Paktika National Average = 36 31 - 36 Farah consumption expenditure at which the members of a household can be expected Zabul 37 - 50 to meet their basic needs (comprised of food and non-food consumption). 51 - 60 Per-capita monthly total consumption is the value of food and non-food items 61 - 76 Kandahar consumed by a household in a month (including the use value of durable goods and housing) divided by the household size. Nimroz Hilmand The poverty gap index measures the depth of poverty, by calculating the mean aggregate consumption shortfall relative to the poverty line across the whole population. The poverty gap gives an indication of the total resources required to bring all the poor up to the level -

Jalalabad & Eastern Afghanistan

© Lonely Planet Publications 181 EASTERN AFGHANISTAN Jalalabad & JALALABAD & Eastern Afghanistan ﺟﻼل ﺑﺎد و ﺷﺮق اﻓﻐﺎﻧﺴﺘﺎن Think of the great clichés of the Afghan character and you’ll be transported to Afghani- stan’s rugged east. Tales of honour, hospitality and revenge abound here, as hardy fighters defend the lonely mountain passes that lead to the Indian subcontinent. For Afghan, read Pashtun: the dominant ethnic group in the east whose tribal links spill across the border deep into Pakistan. Jalalabad is the region’s most important city. Founded by the Mughals as a winter retreat, it sits in an area with links back to when Afghanistan was a Buddhist country and a place of monasteries, pilgrims and prayer wheels. Sweltering in summer, you can quench your thirst with a mango juice before heading for the cooler climes of the Kabul Plateau, via the jaw-dropping Tangi Gharu Gorge. A stone’s throw from Jalalabad is the Khyber Pass, the age-old gateway to the Indian subcontinent. Getting your passport stamped here as you slip between Afghanistan and Pakistan is to experience one of Asia’s most evocative border crossings. If you’ve been in Afghanistan a while, you might find the sudden Pakistani insistence on providing you with an armed guard for your onward journey a little bemusing. Sadly much of the east remains out of bounds to travellers. The failures of post- conflict reconstruction have allowed an Islamist insurgency to smoulder among the peaks and valleys that dominate this part of the country. The beautiful woods and slopes of Nuristan – long a travellers’ grail – remain as distant a goal as ever and the current climate means that carefully checking security issues remains paramount before any trip to the region. -

Knowledge on Fire: Attacks on Education in Afghanistan Risks and Measures for Successful Mitigation

Knowledge on Fire: Attacks on Education in Afghanistan Risks and Measures for Successful Mitigation September 2009 CARE International in Afghanistan and the Afghan Ministry of Education gratefully acknowledge the financial, technical, and moral support of the World Bank as the initiator and champion of this study, and in particular, Asta Olesen and Joel Reyes, two dedicated members of the Bank’s South Asia regional Team. We would further like to thank all of the respondents who gave of their time, effort, and wisdom to help us better understand the phenomenon of attacks on schools in Afghanistan and what we may be able to do to stop it. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. Author: Marit Glad Assistants: Massoud Kohistani and Abdul Samey Belal Desk research, elaboration of tools and trainings of survey team: Waleed Hakim. Data collection: Coordination of Afghan Relief/Organization for Sustainable Development and Research (CoAR/OSDR). This study was conducted by CARE on behalf of the World Bank and the Ministry of Education, with the assistance of CoAR/OSDR. Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary.................................................................................................. 1 2 Introduction............................................................................................................... 6 2.1 HISTORY..............................................................................................................................7