Caring for Their Own: a Stronger Afghan Response to Civilian Harm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justice & Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar

Justice & Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar M AY 2014 Above: Behsud Bridge, Nangarhar Province (Photo by TLO) A TLO M A P P I N G R EPORT Justice and Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar May 2014 In Cooperation with: © 2014, The Liaison Office. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher, The Liaison Office. Permission can be obtained by emailing [email protected] ii Acknowledgements This report was commissioned from The Liaison Office (TLO) by Cordaid’s Security and Justice Business Unit. Research was conducted via cooperation between the Afghan Women’s Resource Centre (AWRC) and TLO, under the supervision and lead of the latter. Cordaid was involved in the development of the research tools and also conducted capacity building by providing trainings to the researchers on the research methodology. While TLO makes all efforts to review and verify field data prior to publication, some factual inaccuracies may still remain. TLO and AWRC are solely responsible for possible inaccuracies in the information presented. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Cordaid. The Liaison Office (TL0) The Liaison Office (TLO) is an independent Afghan non-governmental organization established in 2003 seeking to improve local governance, stability and security through systematic and institutionalized engagement with customary structures, local communities, and civil society groups. -

Page 1 Issue 66 Coalition

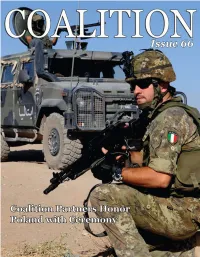

Issue 66 Coalition Page 1 IN THIS ISSUE 4 Coalition Partners Honor Poland with Ceremony Finnish Air Force’s Expeditionary Unit Passes NATO 5 Evaluation Operation Rah-e-Nijat (‘Path to Salvation’) 6 Pakistan Armed Forces’ Crackdown on Taliban The Italian Provincial Reconstruction Team at Chairman 8 BG Gilles Lemoine, France Work for Afghanistan Chief of Coalition Public Affairs Team 10 Kapisa Provincial Reconstruction Team Col. José D. Arias, Dominican Republic Coalition Bulletin Staff 11 Polish - British Exercise Senior Editor CPT Dritor Papa, Albania 12 Georgia’s Significant Contribution to ISAF Mission Editorial Staff LTC Michel C. Escudie, USA Provincial Reconstruction Team of Ghowr Supervise LTC Ali E. Al Kuwari, Qatar 14 Projects Implemented on Lithuania’s Funding MAJ Ghazanfar Iqbal, Pakistan U.S., Pakistan Air Forces Conduct CPT Ehab El-Saheb, Jordan 15 Air Refueling Information Exchange Editor’s Note By the generous permission of our NATO partners, the Coalition is pleased to bring you stories covering the activities of the International Security Assistance Force. As ISAF and the Coalition are separate entities, ISAF stories will be de- noted by the NATO logo at the top of each page when they appear. Cover Pages Front Cover: Herat, Afghanistan - Italian soldiers conduct a patrol du- ring training at Camp Arena, ISAF, Regional Command West Headquarters (ISAF photo by U.S. Air Force TSgt Laura K. Smith) Courtesy of: www.nato.int/isaf Back Cover: Kandahar, Afghanistan--Senior Aircraftman Joe Ralph, a soldier from the 3rd Squadron Royal Air Force Regiment A-flight, hands a bottle of water to a local child during an International Security Assistance Force patrol. -

NATO Airstrike Magnifies Political Divide Over the War in Afghanistan

Nxxx,2009-09-05,A,009,Bs-BW,E3 THE NEW YORK TIMES INTERNATIONAL SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 2009 ØØN A9 NATO Airstrike Magnifies Political Divide Over the War in Afghanistan governor of Ali Abad, Hajji Habi- From Page A1 bullah, said the area was con- with the Afghan people.” trolled by Taliban commanders. Two 14-year-old boys and one The Kunduz area was once 10-year-old boy were admitted to calm, but much of it has recently the regional hospital here in Kun- slipped under the control of in- duz, along with a 16-year-old who surgents at a time when the Oba- later died. Mahboubullah Sayedi, ma administration has sent thou- a spokesman for the Kunduz pro- sands of more troops to other vincial governor, said most of the parts of the country to combat an estimated 90 dead were militants, insurgency that continues to gain judging by the number of charred strength in many areas. pieces of Kalashnikov rifles The region is patrolled mainly found. But he said civilians were by NATO’s 4,000-member Ger- also killed. man force, which is barred by In explaining the civilian German leaders from operating deaths, military officials specu- in combat zones farther south. lated that local people were con- The United States has 68,000 scripted by the Taliban to unload troops in Afghanistan, more than the fuel from the tankers, which any other nation; other countries were stuck near a river several fighting under the NATO com- miles from the nearest villages. mand have a combined total of about 40,000 troops here. -

CB Meeting PAK/AFG

Polio Eradication Initiative Afghanistan Current Situation of Polio Eradication in Afghanistan Independent Monitoring Board Meeting 29-30 April 2015,Abu Dhabi AFP cases Classification, Afghanistan Year 2013 2014 2015 Reported AFP 1897 2,421 867 cases Confirmed 14 28 1 Compatible 4 6 0 VDPV2 3 0 0 Discarded 1876 2,387 717 Pending 0 0 *149 Total of 2,421 AFP cases reported in 2014 and 28 among them were confirmed Polio while 6 labelled* 123as Adequatecompatible AFP cases Poliopending lab results 26 Inadequate AFP cases pending ERC 21There Apr 2015 is one Polio case reported in 2015 as of 21 April 2015. Region wise Wild Poliovirus Cases 2013-2014-2015, Afghanistan Confirmed cases Region 2013 2014 2015 Central 1 0 0 East 12 6 0 2013 South east 0 4 0 Districts= 10 WPV=14 South 1 17 1 North 0 0 0 Northeast 0 0 0 West 0 1 0 Polio cases increased by 100% in 2014 Country 14 28 1 compared to 2013. Infected districts increased 2014 District= 19 from 10 to 19 in 2014. WPV=28 28 There30 is a case surge in Southern Region while the 25Eastern Region halved the number of cases20 in comparison14 to 2013 Most15 of the infected districts were in South, East10 and South East region in 2014. No of AFP cases AFP of No 1 2015 5 Helmand province reported a case in 2015 District= 01 WPV=01 after0 a period of almost two months indicates 13 14 15 Year 21continuation Apr 2015 of low level circulation. Non Infected Districts Infected Districts Characteristics of polio cases 2014, Afghanistan • All the cases are of WPV1 type, 17/28 (60%) cases are reported from Southern region( Kandahar-13, Helmand-02, and 1 each from Uruzgan and Zabul Province). -

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

Environment Scan: 01-15 Dec 2017 China

ENVIRONMENT SCAN: 01-15 DEC 2017 CHINA (Geo-Strat, Geo-Politics & Geo Economics) Brig Rajeev Kumar Bhutani (Retd) World Political Parties Dialogue Concludes with ‘Beijing Initiative’. One of the biggest meetings of global political parties wrapped-up in Beijing on 3 December 2017. It was the first major multilateral diplomacy event hosted by China after the recently concluded 19th CPC National Congress. It was also the first time the CPC held a high-level meeting with such a wide range of political parties from around the world. Over 600 delegates representing nearly 300 political parties and political organizations from over 120 countries attended the meeting.The meeting was officially reported to be a complete success with a broad consensus reached. Year end - China Focus: From Follower to Leader: China Emerges at High-Tech Frontier. After years of focusing on innovation, China has caught up fast. Silicon Valley has long been considered the most viable option for starting a business in the tech sector. Now, this is beginning to change. Known as "sea turtles," a growing number of overseas-educated Chinese are returning to their home country, turning down opportunities in Silicon Valley to make a splash in China's emerging tech sector. As the number of Chinese students at overseas universities surged to 544,500 in 2016, the number of sea turtles also surged, with 432,500 returning to China last year, nearly 60 percent more than 2012, according to the Ministry of Education. The reverse brain drain has benefited China's tech companies. A brilliant example is Royole, a company founded in 2012 by "sea turtle" Liu Zihong, a Stanford graduate. -

AFGHANISTAN - Base Map KYRGYZSTAN

AFGHANISTAN - Base map KYRGYZSTAN CHINA ± UZBEKISTAN Darwaz !( !( Darwaz-e-balla Shaki !( Kof Ab !( Khwahan TAJIKISTAN !( Yangi Shighnan Khamyab Yawan!( !( !( Shor Khwaja Qala !( TURKMENISTAN Qarqin !( Chah Ab !( Kohestan !( Tepa Bahwddin!( !( !( Emam !( Shahr-e-buzorg Hayratan Darqad Yaftal-e-sufla!( !( !( !( Saheb Mingajik Mardyan Dawlat !( Dasht-e-archi!( Faiz Abad Andkhoy Kaldar !( !( Argo !( Qaram (1) (1) Abad Qala-e-zal Khwaja Ghar !( Rostaq !( Khash Aryan!( (1) (2)!( !( !( Fayz !( (1) !( !( !( Wakhan !( Khan-e-char Char !( Baharak (1) !( LEGEND Qol!( !( !( Jorm !( Bagh Khanaqa !( Abad Bulak Char Baharak Kishim!( !( Teer Qorghan !( Aqcha!( !( Taloqan !( Khwaja Balkh!( !( Mazar-e-sharif Darah !( BADAKHSHAN Garan Eshkashem )"" !( Kunduz!( !( Capital Do Koh Deh !(Dadi !( !( Baba Yadgar Khulm !( !( Kalafgan !( Shiberghan KUNDUZ Ali Khan Bangi Chal!( Zebak Marmol !( !( Farkhar Yamgan !( Admin 1 capital BALKH Hazrat-e-!( Abad (2) !( Abad (2) !( !( Shirin !( !( Dowlatabad !( Sholgareh!( Char Sultan !( !( TAKHAR Mir Kan Admin 2 capital Tagab !( Sar-e-pul Kent Samangan (aybak) Burka Khwaja!( Dahi Warsaj Tawakuli Keshendeh (1) Baghlan-e-jadid !( !( !( Koran Wa International boundary Sabzposh !( Sozma !( Yahya Mussa !( Sayad !( !( Nahrin !( Monjan !( !( Awlad Darah Khuram Wa Sarbagh !( !( Jammu Kashmir Almar Maymana Qala Zari !( Pul-e- Khumri !( Murad Shahr !( !( (darz !( Sang(san)charak!( !( !( Suf-e- (2) !( Dahana-e-ghory Khowst Wa Fereng !( !( Ab) Gosfandi Way Payin Deh Line of control Ghormach Bil Kohestanat BAGHLAN Bala !( Qaysar !( Balaq -

2. AFGHANISTAN Stalled Peace Process Under Threat

IRC WATCHLIST 2021 16 IRC WATCHLIST 2021 17 2. AFGHANISTAN Stalled peace process under threat KEY FACTS PROBABILITY IMPACT CONSTRAINTS ON HUMAN THREAT Population: 38.9 million 10 8 COUNTRY RESPONSE EXISTING PRESSURES NATURAL THREAT 18.4 million people in need of humanitarian aid 7 9 ON POPULATION 16.9 million people facing crisis or worse levels of food insecurity (IPC 3+) Afghanistan has risen to second on Watchlist because of its high exposure to the triple threats of conflict, COVID-19 and 3 million people internally displaced due to conflict climate change and uncertainty over the stalled peace process and violence between the government and the Taliban. 1.2 million IDPs due to natural disasters Even after four decades of crises, humanitarian needs in Afghanistan are growing rapidly amid COVID-19 and unrelenting violence, with the 2.8 million Afghan refugees number of people in need for 2021 nearly doubling compared to early 2020. Needs could rise rapidly in 2021 if intra-Afghan peace talks fail 6,000 civilian casualties in the first three quarters of to make progress, particularly amid uncertainty about the continued 2020 US military presence in the country. The global pandemic and climate- related disasters are exacerbating needs for Afghans, many of whom 130th (of 195 countries) for capability to prevent and have lived through decades of conflict, chronic poverty, economic crises, mitigate epidemics and protracted displacement. Some armed groups oppose the peace talks and so the security situation in Afghanistan will remain volatile 50.8% of women over 15 report they have ever experi- regardless of that process, with violence continuing to drive humanitarian enced physical and/or sexual violence from an intimate needs and civilian casualties. -

Afghanistan: Compilation of Country of Origin Information (COI)

Afghanistan: Compilation of Country of Origin Information (COI) Relevant for Assessing the Availability of an Internal Flight, Relocation or Protection Alternative (IFA/IRA/IPA) to Kabul December 2019 This document provides decision-makers with relevant country of origin information (COI) for assessing the availability of an internal flight, relocation or protection alternative (IFA/IRA/IPA) in Kabul for Afghans who originate from elsewhere in Afghanistan and who have been found to have a well-founded fear of persecution in relation to their home area, or who would face a real risk of serious harm in their home area. UNHCR recalls its position that given the current security, human rights and humanitarian situation in Kabul, an IFA/IRA is generally not available in the city. See: UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Eligibility Guidelines for Assessing the International Protection Needs of Asylum-Seekers from Afghanistan, 30 August 2018, https://www.refworld.org/docid/5b8900109.html, p. 114. Table of Contents 1. The relevance of Kabul as an IFA/IRA: the security situation for civilians in Kabul ............. 2 1.1 Security Trends and Impact on Civilian Population in 2019 ................................................. 2 1.2 Presence and Activity of the Taliban in Kabul....................................................................... 6 1.3 Presence and Activity of ISIL in Kabul .................................................................................. 6 1.4 Other Security Threats in Kabul ........................................................................................... -

(SIKA) – East Final Report

Stability in Key Areas (SIKA) – East Final Report ACKU 2 ACKU Ghazni Province_Khwaja Umari District_Qala Naw Girls School Sport Field (PLAY) opening ceremony ii Stability in Key Areas (SIKA) – East Final Report ACKU The authors’ views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government iii Name of USAID Activity: Afghanistan Stability in Key Areas (SIKA) - East Name of Prime Contractor: AECOM International Development $144,948,162.00 Total funding: Start date: December 7, 2011 Option period: December 3, 2013 End date: September 6, 2015 Geographic locations: Ghazni Province: Andar, Bahrami Shahid, Dih Yak, Khwaja Umari, Qarabagh, and Muqur Khost Province: Gurbuz, Jaji Maidan, Mando Zayi, Tani, and Nadir Shah Kot Logar Province: Baraki Barak, Khoshi, and Mohammad Agha Maydan Wardak Province: Chaki Wardak, Jalrez, Nirkh, Saydabad and Maydan Shahr Paktya Province: Ahmad Abad, Laja Ahmad Khail, Laja Mangal, Zadran, Garda Serai, Zurmat, Ali Khail, Mirzaka, and Sayed Karam Paktika Province: Sharan and Yosuf Khel Overall goals and objectives: SIKA – East promotes stabilization in key areas by supporting GIRoA at the district level, while coordinating efforts at the provincial level to implement community led development and governance initiatives that respond to the population’s needs and concerns to build confidence, promote stability, and increase the provision of basic services. • Address Instability and Respond to Concerns: Provincial and District Entities increasingly address Expected Results: sources of instability and take measures to respond to the population’s development and governance concerns. • Enable Access to Services: Provincial and District entities understand what organizations and provincial line departments work within their geographic areas, ACKUwhat kind of services they provide, and how the population can access those services. -

Humanitarian Overview - Farah Province OCHA Contact: Shahrokh Pazhman

Humanitarian Overview - Farah Province OCHA Contact: Shahrokh Pazhman February 2014 http://afg.humanitarianresponse.info/ Context: Farah province is the most contested in the Western Region with civilians in the northern, central and eastern districts significantly exposed to conflict between ANSF and AGEs. Basic services provision outside of the provincial capital is minimal. The province has few resources, while insecurity has affected the presence and activity of NGOs and the funding of Donors. Key Messages 1. The province has the highest risk profile in the Western Region and one of the highest for Afghanistan as a result of poor access to basic health services, restricted humanitarian access and exposure to drought. Insecurity severely hampers the delivery of basic services and humanitarian assistance to Bala Buluk, Bakwa, Gulistan, and Purchaman. More than a third of the population in the province suffers from poor access to health care centres and very low vaccination coverage. Access strategies as well institutional commitment by relevant departments are urgently required to improve this negative indicator. The limited presence of humanitarian organization must be offset by additional monitoring from Hirat-based regional clusters and regular engagement with provincial authorities. People in Need Population (CSO 2012) Humanitarian Organizations Transition Status Present with Current Operations 6,302 conflict IDPs from Total: 482,400 UNICEF, UNHCR, WHO, IOM, CHA, Fully transferred to the 2011 to 2013 (UNHCR) Male: 51.3% - Female: 48.7% VWO, ARCS, ICRC, and VARA Afghan National Army, 40,033 natural disaster Urban:7.3% - Rural: 92.7% 31 December 2012 affected from 2012 to 2013 (NATO). (IOM) 1,400 evicted from informal settlement (DoRR) plus 1,500 protracted IDPs living under tents since 1990s. -

Special Report on Kunduz Province

AFGHANISTAN HUMAN RIGHTS AND PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN ARMED CONFLICT SPECIAL REPORT ON KUNDUZ PROVINCE © 2015/Xinhua United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Kabul, Afghanistan December 2015 AFGHANISTAN HUMAN RIGHTS AND PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN ARMED CONFLICT SPECIAL REPORT ON KUNDUZ PROVINCE United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Kabul, Afghanistan December 2015 Photo on Front Cover © 2015/ Jawed Omid/Xinhua. A man searches for the bodies of his relatives inside the ruins of the Médecins Sans Frontières hospital in Kunduz city. (On 3 October, a United States AC-130 aircraft carried out a series of airstrikes against the hospital, resulting in at least 30 deaths and 37 injured). Photo taken on 11 October 2015. "Citizens of Kunduz were subjected to a horrifying ordeal. The street by street fighting coupled with a breakdown of the rule of law created an environment where civilians were subjected to shooting, other forms of violence, abductions, denial of medical care and restrictions of movement out of the city.” Nicholas Haysom, United Nations Special Representative of the Secretary-General in Afghanistan, Kabul, 25 October 2015. “This event was utterly tragic, inexcusable, and possibly even criminal. International and Afghan military planners have an obligation to respect and protect civilians at all times, and medical facilities and personnel are the object of a special protection. These obligations apply no matter whose air force is involved, and irrespective of the location." United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein, Geneva, 3 October 2015, public statement about attack against the Médecins Sans Frontières hospital.