Bruckner Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saisonprogramm 2019/20

19 – 20 ZWISCHEN Vollendeter HEIMAT Genuss TRADITION braucht ein & BRAUCHTUM perfektes MODERNE Zusammenspiel KULTURRÄUME NATIONEN Als führendes Energie- und Infrastrukturunternehmen im oberösterreichischen Zentralraum sind wir ein starker Partner für Wirtschaft, Kunst und Kultur und die Menschen in der Region. Die LINZ AG wünscht allen Besucherinnen und Besuchern beste Unterhaltung. LINZ AG_Brucknerfest 190x245 mit 7mm Bund.indd 1 30.01.19 09:35 6 Vorworte 12 Saison 19/20 16 Abos 19/20 22 Das Große Abonnement 32 Sonntagsmatineen 42 Kost-Proben 44 Das besondere Konzert 100 Moderierte Foyer-Konzerte am Sonntagnachmittag 50 Chorkonzerte 104 Musikalischer Adventkalender 54 Liederabende 112 BrucknerBeats 58 Streichquartette 114 Russische Dienstage INHALTS- 62 Kammermusik 118 Musik der Völker 66 Stars von morgen 124 Jazz 70 Klavierrecitals 130 BRUCKNER’S Jazz 74 C. Bechstein Klavierabende 132 Gemischter Satz 80 Orgelkonzerte VERZEICHNIS 134 Comedy.Music 84 Orgelmusik zur Teatime 138 Serenaden 88 WortKlang 146 Kooperationen 92 Ars Antiqua Austria 158 Jugend 96 Hier & Jetzt 162 Kinder 178 Kalendarium 193 Team Brucknerhaus 214 Saalpläne 218 Karten & Service 5 Kunst und Kultur sind anregend, manchmal im flüge unseres Bruckner Orchesters genießen Hommage an das Genie Anton Bruckner Das neugestaltete Musikprogramm erinnert wahrsten Sinn des Wortes aufregend – immer kann. Dass auch die oberösterreichischen Linz spielt im Kulturleben des Landes Ober- ebenso wie das Brucknerfest an das kompo- aber eine Bereicherung unseres Lebens, weil Landesmusikschulen immer wieder zu Gast österreich ohne Zweifel die erste Geige. Mit sitorische Schaffen des Jahrhundertgenies sie die Kraft haben, über alle Unterschiedlich- im Brucknerhaus Linz sind, ist eine weitere dem internationalen Brucknerfest, den Klang- Bruckner, für den unsere Stadt einen Lebens- keiten hinweg verbindend zu wirken. -

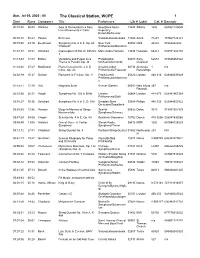

5, 2020 - 00 the Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sun, Jul 05, 2020 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 05:50 Watkins Soul of Remembrance from New Black Music 13225 Albany 1200 034061120025 Five Movements in Color Repertory Ensemble/Dunner 00:08:3505:43 Paulus Berceuse Yolanda Kondonassis 11483 Azica 71281 787867128121 00:15:4844:19 Beethoven Symphony No. 6 in F, Op. 68 New York 08852 CBS 42222 07464422222 "Pastoral" Philharmonic/Bernstein 01:01:37 10:51 Schubert Impromptu in B flat, D. 935 No. Marc-Andre Hamelin 13496 Hyperion 68213 034571282138 3 01:13:4317:49 Britten Variations and Fugue on a Philadelphia 04033 Sony 62638 074646263822 Theme of Purcell, Op. 34 Orchestra/Ormandy Classical 01:33:02 27:47 MacDowell Piano Concerto No. 2 in D Amato/London 00734 Archduke 1 n/a minor, Op. 23 Philharmonic/Freeman Recordings 02:02:1910:37 Dvorak Romance in F minor, Op. 11 Frank/Czech 05323 London 460 316 028946031629 Philharmonic/Mackerra s 02:14:1117:25 Dett Magnolia Suite Denver Oldham 05092 New World 367 n/a Records 02:33:0626:51 Haydn Symphony No. 102 in B flat London 00664 London 414 673 028941467324 Philharmonic/Solti 03:01:2730:36 Schubert Symphony No. 6 in C, D. 589 Dresden State 03988 Philips 446 539 028944653922 Orchestra/Sawallisch 03:33:3312:36 Hanson Elegy in Memory of Serge Seattle 00825 Delos 3073 013491307329 Koussevitsky Symphony/Schwarz 03:47:2409:55 Chopin Scherzo No. 4 in E, Op. 54 Benjamin Grosvenor 10752 Decca 478 3206 028947832065 03:58:49 13:08 Harbach One of Ours - A Cather Slovak Radio 08416 MSR 1252 681585125229 Symphony Symphony/Trevor 04:13:1227:41 Chadwick String Quartet No. -

Rubinstein Festival

ES THE ISRAEL PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA RUBINSTEIN FESTIVAL TWO RECITALS: JERUSALEM ■ TEL AVIV TWO SPECIAL CONCERTS: TEL AVIV CONDUCTOR: ELIAHU iNBAL September 1968 ARTUR RUBINSTEIN ne Israel Philharmonic Orchestra again a galley slave,” Rubinstein answered : returned each year since then to triumph as the pleasure and profound honour to "Excuse me, Madame,a galley slave is ant successes. welcome the illustrious Pianist, ARTUR condemned to work he detests, but I am RUBINSTEIN, whose artistry has brought in love with mine; madly in love. It isn’t Rubinstein married the beautiful Aniela enjoyment and spiritual fulfillment to many work, it is passion and always pleasurable. Mlynarski, daughter of conductor Emil thousands of music lovers in our country, I give an average of a hundred concerts Mlynarski under whose baton he had to yet another RUBINSTEIN FESTIVAL. The a year. One particular year, I toted up one played in Warsaw when he was 14. Four great virtuoso, whose outstanding inter hundred and sixty-two on four continents. children were born to the Rubinsteins, pretation is so highly revered, has retained That, I am sure, is what keeps me young.” two boys and two girls. the spontaneity of youthfulness despite the Artur Rubinstein was born in Warsaw, the In 1954 Rubinstein acquired his home in passing of time. youngest of seven children. His remark Paris, near the house in which Debussy able musical gifts revealed themselves spent the last 13 years of his life, by the Artur Rubinstein could now be enjoying Bois de Boulogne. It is there that he now the ease and comforts of ‘‘The Elder very early and at the age of eight, after receiving serious encouragement from lives in between the tours that take him Statesman”, with curtailed commitments all round the world. -

West Side Story

To Our Readers ow can something be as fresh, as bril Hliant, as explosively urgent as "West Side Story," and be 50 years old? How can this brand new idea for the American theatre have been around for half a century? Leonard Bernstein used to say that he wished he could write the Great American Opera. He was still designing such a project shortly before his death. But in retrospect, we can say that he fulfilled his wish. "West Side Story" is performed to enthusiastic audiences in opera houses around the world - recently in La Scala and, before this year is out, at the Theatre du Chatelet in Paris. Is there a Broadway revival in the works? The signs are highly auspicious. In this issue, we celebrate "West Side Story": its authors, its original performers, and its continuing vital presence in the world. Chita Rivera regrets that, due to scheduling conflicts, she was unable to contribute to this issue by print time. [ wEst SIDE ·sronv L "West Side Story" continues to break ground to this very day. Earlier this year, the show was performed by inmates at Sing Sing. A few months later, it was presented as part of a conflict resolution initiative for warring street gangs in Seattle. And if there's a heaven, Leonard Bernstein was up there dancing for joy last summer while Gustavo Dudamel led his sensational 200-piece Simon Bolfvar Youth Orchestra in the "Mambo" at the Proms in London. The audience went bonkers. Check it out: http://www.dailymotion.com/swf/ 6pXLfR60dUfQNjMYZ There are few theatrical experiences as reliably thrilling as a student production of "West Side Story". -

Graham Ross Conductor/Composer

Graham Ross Conductor/Composer Ikon Arts Management Ltd “To say he’s impressive would be an understatement” 2-6 Baches Street London N1 6DN The Telegraph +44 (0)20 7354 9199 [email protected] Website www.grahamross.com www.ikonarts-editionpeters.com Contact Hannah Marsden Email [email protected] Graham Ross has established an exceptional reputation as a sought-after conductor and composer of a very broad range of repertoire. His performances around the world and his extensive discography have earned consistently high international praise, including a Diapason d’Or, Le Choix de France Musique and a Gramophone Award nomination. As a guest conductor he has worked with Aalborg Symfoniorkester, Australian Chamber Orchestra, Aurora Orchestra, European Union Baroque Orchestra, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Royal College of Music Symphony Orchestra, and Salomon Orchestra, making his debuts in recent seasons with the BBC Concert Orchestra, BBC Singers, DR Vokal Ensemblet (Danish National Vocal Ensemble), London Mozart Players, London Philharmonic Orchestra and Malaysian Philharmonic Orchestra. He is co-founder and Principal Conductor of The Dmitri Ensemble, and, since 2010, Fellow and Director of Music at Clare College, Cambridge, where he directs the internationally-renown Choir. Highlights in the 2019/20 season include concerts with the Choir of Clare College in Shanghai, Hong Kong, Macau, the Netherlands, Germany, and across the UK, and return engagements to BBC Singers, Aalborg Symfoniorkester and DR Vokal Ensemblet. In recent seasons Graham Ross's work has taken him to Sydney Opera House, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore and across the USA, Canada and Europe. At the age of 25 he made his BBC Proms and Glyndebourne debuts, with other opera work taking him to Jerusalem, London, Aldeburgh and Provence. -

Martinu° Classics Cello Concertos Cello Concertino

martinu° Classics cello concertos cello concertino raphael wallfisch cello czech philharmonic orchestra jirˇí beˇlohlávek CHAN 10547 X Bohuslav Martinů in Paris, 1925 Bohuslav Martinů (1890 – 1959) Concerto No. 1, H 196 (1930; revised 1939 and 1955)* 26:08 for Cello and Orchestra 1 I Allegro moderato 8:46 2 II Andante moderato 10:20 3 III Allegro – Andantino – Tempo I 7:00 Concerto No. 2, H 304 (1944 – 45)† 36:07 © P.B. Martinů/Lebrecht© P.B. Music & Arts Photo Library for Cello and Orchestra 4 I Moderato 13:05 5 II Andante poco moderato 14:10 6 III Allegro 8:44 7 Concertino, H 143 (1924)† 13:54 in C minor • in c-Moll • en ut mineur for Cello, Wind Instruments, Piano and Percussion Allegro TT 76:27 Raphael Wallfisch cello Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Bohumil Kotmel* • Josef Kroft† leaders Jiří Bělohlávek 3 Miloš Šafránek, in a letter that year: ‘My of great beauty and sense of peace. Either Martinů: head wasn’t in order when I re-scored it side lies a boldly angular opening movement, Cello Concertos/Concertino (originally) under too trying circumstances’ and a frenetically energetic finale with a (war clouds were gathering over Europe). He contrasting lyrical central Andantino. Concerto No. 1 for Cello and Orchestra had become reasonably well established in set about producing a third version of his Bohuslav Martinů was a prolific writer of Paris and grown far more confident about his Cello Concerto No. 1, removing both tuba and Concerto No. 2 for Cello and Orchestra concertos and concertante works. Among own creative abilities; he was also receiving piano from the orchestra but still keeping its In 1941 Martinů left Paris for New York, just these are four for solo cello, and four in which much moral support from many French otherwise larger format: ahead of the Nazi occupation. -

Grosser Saal Klangwolke Brucknerhaus Präsentiert Von Der Linz Ag Linz

ZWISCHEN CREDO Vollendeter Genuss TRADITION BEKENNTNIS braucht ein & GLAUBE perfektes MODERNE Zusammenspiel RELIGION Als führendes Energie- und Infrastrukturunternehmen im oberösterreichischen Zentralraum sind wir ein starker Partner für Wirtschaft, Kunst und Kultur und die Menschen in der Region. Die LINZ AG wünscht allen Besucherinnen und Besuchern beste Unterhaltung. bezahlte Anzeige LINZ AG_Brucknerfest 190x245.indd 1 02.05.18 10:32 6 Vorworte 12 Saison 2018/19 16 Abos 2018/19 22 Das Große Abonnement 32 Sonntagsmatineen 44 Internationale Orchester 50 Bruckner Orchester Linz 56 Kost-Proben 60 Das besondere Konzert 66 Oratorien 128 Hier & Jetzt 72 Chorkonzerte 134 Moderierte Foyer-Konzerte INHALTS- 78 Liederabende 138 Musikalischer Adventkalender 84 Streichquartette 146 BrucknerBeats 90 Kammermusik 150 Russische Dienstage 96 Stars von morgen 154 Musik der Völker 102 Klavierrecitals 160 Jazz VERZEICHNIS 108 Orgelkonzerte 168 Jazzbrunch 114 Orgelmusik zur Teatime 172 Gemischter Satz 118 WortKlang 176 Kinder.Jugend 124 Ars Antiqua Austria 196 Serenaden 204 Kooperationen 216 Kalendarium 236 Saalpläne 242 Karten & Service 4 5 Linz hat sich schon längst als interessanter heimischen, aber auch internationalen Künst- Der Veröffentlichung des neuen Saisonpro- Musik wird heutzutage bevorzugt über diverse und innovativer Kulturstandort auch auf in- lerinnen und Künstlern es ermöglichen, ihr gramms des Brucknerhauses Linz sehen Medien, vom Radio bis zum Internet, gehört. ternationaler Ebene Anerkennung verschafft. Potenzial abzurufen und sich zu entfalten. Für unzählige Kulturinteressierte jedes Jahr er- Dennoch hat die klassische Form des Konzerts Ein wichtiger Meilenstein auf diesem Weg war alle Kulturinteressierten jeglichen Alters bietet wartungsvoll entgegen. Heuer dürfte die nichts von ihrer Attraktivität eingebüßt. Denn bislang auf jeden Fall die Errichtung des Bruck- das ausgewogene und abwechslungsreiche Spannung besonders groß sein, weil es die das Live-Erlebnis bleibt einzigartig – dank der nerhauses Linz. -

Esercizio 2008

esercizio 2008 Estremi approvazione Consiglio di Amministrazione del 21 aprile 2009 e dall’Organo di Indirizzo del 23 aprile 2009 Fondazione Banca del Monte di Lucca Bilancio 2008 Relazione Economico Finanziaria Pag. 2 Bilancio 2008 Fondazione Banca del Monte di Lucca Relazione Economico Finanziaria Indice RELAZIONE AL BILANCIO ........................................................ Sommario................................................................................................. pag. 5 Premessa.................................................................................................. pag. 6 Prima Sezione: l’identità.......................................................................... pag. 8 Seconda Sezione: la gestione del patrimonio ............................................. pag. 27 Terza Sezione: l’attività istituzionale ....................................................... pag. 53 BILANCIO CONTABILE Sommario................................................................................................. pag. 172 Premessa.................................................................................................. pag. 173 Criteri di Valutazione .............................................................................. pag. 173 Schemi di Bilancio ................................................................................... pag. 177 Nota Integrativa ...................................................................................... pag. 182 Rendiconto finanziario di liquidità.......................................................... -

Cyberarts 2018

Hannes Leopoldseder · Christine Schöpf · Gerfried Stocker CyberArts 2018 International Compendium Prix Ars Electronica Computer Animation · Interactive Art + · Digital Communities Visionary Pioneers of Media Art · u19–CREATE YOUR WORLD STARTS Prize’18 Grand Prize of the European Commission honoring Innovation in Technology, Industry and Society stimulated by the Arts INTERACTIVE ART + Navigating Shifting Ecologies with Empathy Minoru Hatanaka, Maša Jazbec, Karin Ohlenschläger, Lubi Thomas, Victoria Vesna Interactive Art was introduced to Prix Ars Electronica farewell and prayers of a dying person into the robot as a key category in 1990. In 2016, in response to a software; seeking life-likeness—computational self, growing diversity of artistic works and methods, the and environmental awareness; autonomous, social, “+” was added, making it Interactive Art +. and unpredictable physical movement; through to Interactivity is present everywhere and our idea of the raising of a robot as one's own child. This is just what it means to engage with technology has shifted a small sample of the artificial ‘life sparks’ in this from solely human–machine interfaces to a broader year’s category. Interacting with such artificial enti- experience that goes beyond the anthropocentric ties draws us into both a practical and ethical dia- point of view. We are learning to accept machines as logue about the future of robotics, advances in this other entities we share our lives with while our rela- field, and their role in our lives and society. tionship with the biological world is intensified by At the same time, many powerful works that deal the urgency of environmental disasters and climate with social issues were submitted. -

Jazzzeitung 2002 / 11

27. Jahrgang Nr. 11-02 www.jazzzeitung.de November 2002 B 07567 PVSt/DPAG Entgelt bezahlt Jazzzeitung Mit Jazz-Terminen ConBrio Verlagsgesellschaft aus Bayern, Hamburg, Brunnstraße 23 93053 Regensburg Mitteldeutschland ISSN 1618-9140 und dem Rest E 2,05 der Republik berichte farewell portrait label portrait dossier Große Namen: die 26. Leipziger Jazztage Unfassbar: zum Tod von Peter Kowald Ready To Play For You: Paul Kuhn Qualität als Rezept: das Label Songlines Ungehorsam: Dietrich Schulz-Köhn S. 4 S. 11 S. 13 S. 16 S. 22–23 Liebe Leserinnen, liebe Leser, die Temperaturen an diesem Tag der ers- ten großen Kälte in München wollten so gar nicht zu den sonnigen Klängen auf WARMEWARME KLÄNGEKLÄNGE AUSAUS DEMDEM SÜDENSÜDEN den neuen CD-Produktionen meiner bei- den Interviewpartner passen. Trotzdem unterhielten wir uns bei griechischem Neue CDs von Lisa Wahlandt & Mulo Francel Bergtee im angenehmen vegetarischen „Bossa Nova Affair“ heißt die neueste CD Restaurant „Prinz Myshkin“ ausnehmend von Lisa Wahlandt und Mulo Francel (Re- gut. Die Ergebnisse des Gesprächs mit zension auf Seite 15 dieser Ausgabe!). der Sängerin Lisa Wahlandt, die überdies Die musikalische „Affäre“ der beiden be- als Titelmädchen diese Ausgabe der Jazz- gann am Bruckner Konservatorium in zeitung ziert, und dem Saxophonisten Linz, wo beide zeitversetzt studierten. Mulo Francel lesen Sie weiter unten auf Mulo hörte Lisas Stimme während ihrer dieser Seite. Rezensionen der beiden CDs Aufnahmeprüfung und verliebte sich – in finden Sie auf Seite 15 dieser Ausgabe die Stimme. Aber erst vier Jahre später, der Jazzzeitung. 1996, begann eine echte Zusammenar- Weniger erfreulich sind die zunehmenden beit, die bis heute ungebrochen weiter Finanzierungsprobleme innovativer Jazz- funktioniert. -

NEUE ANTON BRUCKNER GESAMTAUSGABE NEW ANTON BRUCKNER COMPLETE EDITION Das Projekt the Project

12. Fahne 08.02.16 SYMPHONIE NR. 1 IN C-MOLL Linzer Fassung 1. SATZ Anton Bruckner Allegro Flöte 1. 2. b & b b c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Oboe 1. 2. b & b b c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Einladung zur Subskription / Invitation to subscribe Klarinette 1. 2. in B & b c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Fagott 1. 2. ? b b b c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ NEUE ANTON BRUCKNER GESAMTAUSGABE 1. Solo 1. 2. in F ‰. r j . r & c ∑ ∑ ∑ bœ œ ‰‰ j ‰ ∑ Horn . œ. œ. p 3. 4. in Es & c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ NEW ANTON BRUCKNER COMPLETE EDITION Trompete 1. 2. in C & c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Alt, Tenor b B b b c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Posaune Die Anfangstakte der Symphonie Nr. 1 (Linzer Fassung) im Vergleich The first bars of Symphony No. 1 (Linz Version) – a comparison Bass ? (Detail): (detail): bbb c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Pauken in C u. G ? c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Internationale Bruckner-Gesellschaft – Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Allegro International Bruckner Society – Austrian National Library Violine 1 b & b b c Ó ‰. r ≈ œ œ ≈œ ≈ ≈ j ‰‰. r j ‰‰. r ≈œ œ œ œ œ œ ≈nœ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ≈œ œ p Violine 2 b Patronanz: Wiener Philharmoniker & b b c ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ divisi Patronage: Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Viola B bbb c œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ œ œ œ p . Violoncello ? b b b c œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ. œ œ œ œ p . Kontrabass ? b c œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ b b . œ. -

Swr2 Programm Kw 10

SWR2 PROGRAMM - Seite 1 - KW 10 / 07. - 13.03.2016 Béla Bartók: mehrjährigen Expeditionen die Tier- Montag, 07. März ”Ungarische Bilder” Sz 97 und Pflanzenwelt und beschrieb Hungarian National Philharmonic außerdem einfühlsam die Lebensweise 0.05 ARD-Nachtkonzert Orchestra der Indianer. Seine Bücher zur Julius Rietz: Leitung: Zoltán Kocsis Naturgeschichte Brasiliens und über ”Hero und Leander”, Ouvertüre op. 11 Germain Pinel: die Indianer Nord- und Südamerikas MDR Sinfonieorchester Suite d-Moll mit ihren eindrucksvollen Leitung: Bruno Weil Miguel Yisrael (Laute) Schilderungen und einzigartigen Georg Friedrich Händel: Ludwig van Beethoven: Abbildungen haben bis heute einen Suite Nr. 7 g-Moll HWV 432 Streichtrio D-Dur op. 9 Nr. 2 hohen wissenschaftlichen Wert. Über Ragna Schirmer (Klavier) Trio Zimmermann 50 Tier- und Pflanzenarten tragen den Richard Strauss: William Walton: Namen von Max zu Wied, einem Tanzsuite aus Klavierstücken von Maestoso aus der “Sinfonia Forscher, der zu Unrecht bei uns viel François Couperin concertante” zu schnell in Vergessenheit geraten ist. Staatskapelle Dresden Phyllis Sellick (Klavier) Leitung: Rudolf Kempe City of Birmingham Symphony 8.58 SWR2 Programmtipps Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy: Orchestra Trauermarsch a-Moll op. 103 Leitung: William Walton 9.00 Nachrichten, Wetter MDR Sinfonieorchester Leitung: Bruno Weil 6.00 SWR2 am Morgen 9.05 SWR2 Musikstunde Antonio Vivaldi: darin bis 8.00 Uhr: Brahms in Baden-Baden (1) Konzert g-Moll RV 576 Mit Wolfgang Sandberger Virtuosi Saxoniae 6.00 Aktuell Leitung: Ludwig Güttler ”Nach Baden-Baden habe ich ohnehin Jean Sibelius: 6.30 Kurznachrichten immer eine Art Sehnsucht” – Johannes ”En Saga” op. 9 Brahms wusste, wo es schön ist und Staatskapelle Dresden wo ihn die Natur inspirierte.