Computer Privacy and the Modern Workplace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Descendants of the Anusim (Crypto-Jews) in Contemporary Mexico

Descendants of the Anusim (Crypto-Jews) in Contemporary Mexico Slightly updated version of a Thesis for the degree of “Doctor of Philosophy” by Schulamith Chava Halevy Hebrew University 2009 © Schulamith C. Halevy 2009-2011 This work was carried out under the supervision of Professor Yom Tov Assis and Professor Shalom Sabar To my beloved Berthas In Memoriam CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................7 1.1 THE PROBLEM.................................................................................................................7 1.2 NUEVO LEÓN ............................................................................................................ 11 1.2.1 The Original Settlement ...................................................................................12 1.2.2 A Sephardic Presence ........................................................................................14 1.2.3 Local Archives.......................................................................................................15 1.3 THE CARVAJAL TRAGEDY ....................................................................................... 15 1.4 THE MEXICAN INQUISITION ............................................................................. 17 1.4.1 José Toribio Medina and Alfonso Toro.......................................................17 1.4.2 Seymour Liebman ...............................................................................................18 1.5 CRYPTO‐JUDAISM -

Jason Yehuda Leib Weiner

Jason Yehuda Leib Weiner A Student's Guide and Preparation for Observant Jews ♦California State University, Monterey Bay♦ 1 Contents Introduction 1 Chp. 1, Kiddush/Hillul Hashem 9 Chp. 2, Torah Study 28 Chp. 3, Kashrut 50 Chp. 4, Shabbat 66 Chp. 5, Sexual Relations 87 Chp. 6, Social Relations 126 Conclusion 169 2 Introduction Today, all Jews have the option to pursue a college education. However, because most elite schools were initially directed towards training for the Christian ministry, nearly all American colonial universities were off limits to Jews. So badly did Jews ache for the opportunity to get themselves into academia, that some actually converted to Christianity to gain acceptance.1 This began to change toward the end of the colonial period, when Benjamin Franklin introduced non-theological subjects to the university. In 1770, Brown University officially opened its doors to Jews, finally granting equal access to a higher education for American Jews.2 By the early 1920's Jewish representation at the leading American universities had grown remarkably. For example, Jews made up 22% of the incoming class at Harvard in 1922, while in 1909 they had been only 6%.3 This came at a time when there were only 3.5 millions Jews4 in a United States of 106.5 million people.5 This made the United States only about 3% Jewish, rendering Jews greatly over-represented in universities all over the country. However, in due course the momentum reversed. During the “Roaring 1920’s,” a trend towards quotas limiting Jewish students became prevalent. Following the lead of Harvard, over seven hundred liberal arts colleges initiated strict quotas, denying Jewish enrollment.6 At Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons for instance, Jewish enrollment dropped from 50% in 1 Solomon Grayzel, A History of the Jews (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1959), 557. -

Bring Back Our Boys – Jared Feldshreiber

WEEKLY BRING BACK Candle-lighting/Shabbos ends Friday, June 27: 8:12/9:21 OUR BOYS Vol. III No. 18 (#67) June 26, 2014 • 28 Sivan 5774 Free Lakewood Rabbanim Visit Community Unites New York City Offi cials Queens On Behalf Of At Prayer Gathering For Stand In Solidarity With Beth Medrash Govoha Kidnapped Boys In Israel Israel After Kidnapping Of Three Jewish Teenagers SEE STORY ON P. 55 SEE PHOTOS ON 36/37; ARTICLE ON P. 52 SEE STORY ON P. 39 Shabbos Inbox Blue And White Op-Ed Politics And Ethics Hooked On Healing (D)Anger Tragedy Helplessness Situational To Give Management Brings Unity By Betsalel Steinhart Awareness Or Not To Give Is Derech Eretz By Eytan Kobre By Shmuel Sackett hat can we do in the By Caroline Schumsky face of helplessness? By Abe Fuchs o goes the well-known hy do we do this to W This question is ooo… You want to give joke: ourselves? Why do being asked so many times, somehow, some way. S Husband to Wife: Wwe fi ght like dogs and over the last few days, as our and another person were SYou want to dedicate When I get mad at you, you cats until tragedy strikes? Why darkest fears take shape, as waiting on line at a bank the or allocate, but not so sure never fi ght back. How do you does it take the kidnapping of three boys sit who-knows- Iother day when there was how or where or how often? control your anger? three precious boys to bring us where, as three families lie only one teller available. -

Upcoming Dor Tikvah Events Feb 16-17: Scout Shabbat

Yitro February 3, 2018 (Shevat 18, 5778) www.facebook.com/DorTikvah @DorTikvah Shabbat Times Upcoming Dor Tikvah Events Feb 16-17: Scout Shabbat – Scout activities begin at 10:30 am Friday, February 2 followed by lunch for Scouts and their families at the Davies’. Spirited Friday Night Service with Singing and Ruach Feb 17: Shabbat Shebang 5:35 pm – Mincha/Kabbalat Shabbat/Maariv Feb 18: Cemetery Consecration - stay tuned for more details 5:35 pm –Candle Lighting Feb 25: Breakfast Minyan and Annual Meeting Saturday, February 3 Condolences 9:00 am – Shacharit On behalf of Congregation Dor Tikvah, we extend our deepest (9:53 am – Latest preferable time to say the shema) condolences to Greg, Debbie and Truere Rothschild on the 10:30 am – Shabbat Morning Youth Groups passing of Debbie's grandmother, Ruth Silverman. 5:10 pm – Mincha 6:33 pm - Havdalah Mazel Tov 8:00 pm – Motzai Shabbat Pickup Basketball Congregation Dor Tikvah wishes a hearty Mazel Tov to Yoni & Nechama Alon on becoming grandparents for the 6th time. Baby Kiddush Sponsor: girl was born to their daughter and son-in-law: Batya and Micha Feb 3: Marcie and David Rosenberg in honor of Sammy’s Muskal in Cleveland OH on Monday, January 29th. Birthday • Feb 10: Gerry and Sandy Katz In appreciation of Charles Refuah Shelema Yechil Yeshiahu ben Fradel Moshe Ben Chava Steinert for creation of Dor Tikvah Senior Social Group; Robert Levinson Talia Bat Shoshana and successful completion of Dor Tikvah Cemetery Hodel bat Raozel (Linda Blooma bat Chaya Sara • Feb 17: Adrian Reuben in honor -

Controlling Anger

CONTROLLING ANGER o enjoy harmonious relationships with one’s spouse, family, friends, and Tprofessional associates is a universal human goal. Anger, however, is a character trait that can undermine this basic aspiration. Anger can destroy years of investment in a relationship in a matter of minutes. So why is it that many people are quite content to live with the tendency to become angry? The answer is that many people go through life without ever thinking how destructive anger really is, and conversely, how constructive patience is. And even if someone has this understanding, he may lack practical techniques to control anger. This class will analyze why anger is so destructive and provide insights and tools to help us gain control in the most trying moments. This class will address the following questions: What makes an angry person so frightening to other people? What does an angry person stand to lose and a patient person stand to gain? How does one replace anger with patience? Isn’t it appropriate to be angry sometimes? Is it really possible to overcome a tendency toward anger? Class Outline Section I. What We Stand to Lose Part A. Personal Damage Part B. Social Damage Part C. Undermining Personal and Spiritual Growth Section II. The Benefits of Patience Section III. Tools for Controlling Anger Part A. Forming Positive Habits Part B. Putting Things in Perspective Part C. Developing Humility Part D. Developing Trust in God 1 Bein Adam L’Chavero CONTROLLING ANGER SECTION I. WHAT WE STAND TO LOSE Anger and frustration – not so common, you say? Just consider the following: A large, international retail corporation is now proudly offering its customers “Frustration-free packaging – no dreaded wire ties, no impenetrable plastic clamshells.” This special wrapping is designed to protect valued customers from becoming victims of “wrap rage,” the fury that sets in when it takes a customer more than a nanosecond to get to his new purchase. -

'Standardized Chapel Library Project' Lists

Standardized Library Resources: Baha’i Print Media: 1) The Hidden Words by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 193184707X; ISBN-13: 978-1931847070) Baha’i Publishing (November 2002) A slim book of short verses, originally written in Arabic and Persian, which reflect the “inner essence” of the religious teachings of all the Prophets of God. 2) Gleanings from the Writings of Baha’u’llah by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 1931847223; ISBN-13: 978-1931847223) Baha’i Publishing (December 2005) Selected passages representing important themes in Baha’u’llah’s writings, such as spiritual evolution, justice, peace, harmony between races and peoples of the world, and the transformation of the individual and society. 3) Some Answered Questions by Abdul-Baham, Laura Clifford Barney and Leslie A. Loveless (ISBN-10: 0877431906; ISBN-13 978-0877431909) Baha’i Publishing, (June 1984) A popular collection of informal “table talks” which address a wide range of spiritual, philosophical, and social questions. 4) The Kitab-i-Iqan Book of Certitude by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 1931847088; ISBN-13: 978:1931847087) Baha’i Publishing (May 2003) Baha’u’llah explains the underlying unity of the world’s religions and the revelations humankind have received from the Prophets of God. 5) God Speaks Again by Kenneth E. Bowers (ISBN-10: 1931847126; ISBN-13: 978- 1931847124) Baha’i Publishing (March 2004) Chronicles the struggles of Baha’u’llah, his voluminous teachings and Baha’u’llah’s legacy which include his teachings for the Baha’i faith. 6) God Passes By by Shoghi Effendi (ISBN-10: 0877430209; ISBN-13: 978-0877430209) Baha’i Publishing (June 1974) A history of the first 100 years of the Baha’i faith, 1844-1944 written by its appointed guardian. -

How to Prevent an Intermarriage

How To Prevent an Intermarriage A guide for preventing broken hearts How To Prevent an Intermarriage A guide for preventing broken hearts Rabbi Kalman Packouz © 2004 by Rabbi Kalman Packouz First edition, 1976; Second edition, 1982 Third revised and expanded edition, 2004 Aish HaTorah P.O.B. 14149 Jerusalem, Israel Tel. 9722-628-5666 To contact Rabbi Packouz: 3150 Sheridan Avenue Miami Beach, Fl. 33140 Telephone: (305) 535-2474 Fax: (305) 531-9334 E-mail: [email protected] For a free internet subscription to Rabbi Packouz's Shabbat Shalom Weekly -- Insights into life, personal growth and Torah which is read each week by over 200,000 people – either subscribe from www.shabbatshalom.org or at aish.com/torahportion/shalomweekly Go to www.preventintermarriage.com for more information and free downloads Permission is granted to photocopy whatever sections of this book you may need to communicate with someone you love the benefits of marrying someone Jewish and/or the problems facing an intermarriage. ISBN: 0-87306-371-6 Typeset by: Rosalie Lerch Intermarriage is a recognized threat to the survival of the Jewish people. There is a sore need to meet this threat. After reading How to Stop an Intermarriage twenty years ago before it was published, I wrote, "I am very much encouraged. As the first book in its field, it is more than a beginning. It is excellently done, with cogent arguments, effective suggestions, and positive approaches. It will definitely be an invaluable aid for those who want to know what they can do at this time of crisis." Now the book has proven itself as an effective tool which has helped thousands of parents in their time of need. -

Vayeishev 5758 Volume V Number 12

Beha’alotcha 5776 Volume XXIII Number 41 Toras Aish Thoughts From Across the Torah Spectrum eyes, kill me now, and let me not look upon this my RABBI LORD JONATHAN SACKS evil." (Num. 11:11-15) Covenant & Conversation This for me is the benchmark of despair. here have been times when one passage in Whenever I felt unable to carry on, I would read this today's parsha was for me little less than life- passage and think, "If I haven't yet reached this point, Tsaving. No leadership position is easy. Leading I'm OK." Somehow the knowledge that the greatest Jews is harder still. And spiritual leadership can be Jewish leader of all time had experienced this depth of hardest of them all. Leaders have a public face that is darkness was empowering. It said that the feeling of usually calm, upbeat, optimistic and relaxed. But behind failure does not necessarily mean that you have failed. the faade we can all experience storms of emotion as All it means is that you have not yet succeeded. Still we realise how deep are the divisions between people, less does it mean that you are a failure. To the how intractable are the problems we face, and how thin contrary, failure comes to those who take risks; and the the ice on which we stand. Perhaps we all experience willingness to take risks is absolutely necessary if you such moments at some point in our lives, when we seek, in however small a way, to change the world for know where we are and where we want to be, but the better. -

Torah Weekly — Please Contact Us for Details

For the week ending 6 Adar II 5757 Parshas Pekudei 14 & 15 March 1997 This issue is sponsored Herschel Kulefsky, Attorney at Law, 15 Park Row, New York, NY 10038, 1-212-693-1671 Overview Insights he Book of O.H.M.S. Shmos comes to “...stones of remembrance to the Children of Yisrael” (39:7) its conclusion Ask someone from a non-religious background what it’s like to wear a yarmulke in public for T with this Parsha. the first time. After finishing He will tell you it feels like becoming an ambassador. An ambassador for the Jewish People. all the different parts, An ambassador for Hashem Himself. The entire Jewish People and Hashem may be judged by vessels and garments used the way you now behave. Five minutes ago it was “Hey! - Look at that guy pushing in line!” in the Mishkan, Moshe Now it’s “Hey! - Look at that Jew pushing in line!” gives a complete A Jew, unlike a person of color, always has the option to merge into the background, to shorten accounting and his nose, shorten his name. But as soon as he ‘comes out’ and wears the signs of his Judaism with pride, his actions reflect enumeration of all the not just on himself, but on the whole Jewish People, and on G-d. contributions and of the On the Choshen, the breastplate, that the Kohen Gadol (High Priest) wore, were twelve stones. various clothing and On these stones were inscribed the names of the Tribes of Israel. They were called the ‘stones vessels which had been of remembrance before the Children of Yisrael.’ fashioned. -

A Man Once Character

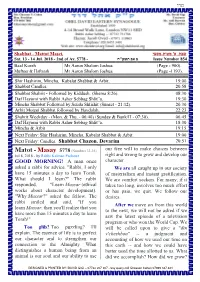

בס"ד שבת פ' מטות-מסעי ,Shabbat - Mattot Masei Issue Number 854 ב אב תשע"ח - Sat. 13 - 14 Jul. 2018 - 2nd of Av, 5778 Baal Koreh Mr Aaron Shalom Joshua (Page - 900). Mufteer & Haftarah Mr Aaron Shalom Joshua (Page -1193). Shir Hashirim, Mincha, Kabalat Shabbat & Arbit. 19:00 Shabbat Candles. 20:58 Shabbat Shahrit - Followed by Kiddush. (Shema 8:26). 08:30 Daf Hayomi with Rabbi Asher Sebbag Shlit”a. 19:30 Mincha Shabbat Followed by Seuda Shlishit (Sunset - 21:12). 20:30 Arbit Motzei Shabbat followed by Havdalah. 22:23 Shahrit Weekday - (Mon. & Thu. - 06:40) (Sunday & Bank/H - 07:30). 06:45 Daf Hayomi with Rabbi Asher Sebbag Shlit”a. 18:30 Mincha & Arbit 19:15 Next Friday: Shir Hashirim, Mincha, Kabalat Shabbat & Arbit. 19:00 Next Friday: Candles. Shabbat Chazon. Devarim 20:51 Matot - Masay 5778 (Numbers 33-36) our free will to make choices between Jul 8, 2018 - by Rabbi Kalman Packouz right and wrong to grow and develop our GOOD MORNING! A man once character. asked a rabbi for advice. "Rabbi, I only We are all caught up in our society have 15 minutes a day to learn Torah. of materialism and instant gratification. What should I learn?" The rabbi We are comfort seekers. For many, if it responded, "Learn Mussar (ethical takes too long, involves too much effort works about character development). or has pain, we quit. We follow our "Why Mussar?" asked the fellow. The desires. rabbi smiled and said, "If you After we move on from this world learn Mussar, then you'll realize that you to the next, we will not be asked if we have more than 15 minutes a day to learn saw the latest episode of a television Torah!" program or who won the World Cup. -

Bo 5778 GOOD MORNING!

בס"ד שבת פ' בא ,Shabbat - Bo Issue Number 829 ד שבט תשע"ח - Sat. 19 - 20 Jan. 2018 - 4th of Sh'vat, 5778 Baal Koreh Mr Arian Aharon Reyhanian (Page-340). Mufteer & Haftarah Mr Haim L. Eida (Page -9). Mincha, Shir Hashirim, Kabalat Shabbat & Arbit. 15:50 Shabbat Candles. 16:11 Shabbat Shahrit - Followed by Kiddush. (Shema 9:27). 08:30 Mincha Shabbat Followed by Seuda Shlishit. * (Sunset - 16:28). 15:50 Daf Hayomi with Rabbi Asher Sebbag Shlit”a. * Arbit Motzei Shabbat followed by Havdalah. 17:24 Shahrit Weekday - (Mon. & Thu. - 06:40) (Sunday & B/H - 07:30). 06:45 Mincha & Arbit 16:00 Daf Hayomi with Rabbi Asher Sebbag Shlit”a. 16:40 Next Friday: Mincha, Shir Hashirim, Kabalat Shabbat & Arbit. 16:00 Next Friday: Candles. Shabbat Parashat Beshalach. 16:23 Rabbi Noah Weinberg, of blessed Bo (Exodus 10:1-13:16) memory, the founder and leader of Aish Bo 5778 HaTorah, would often engage a new GOOD MORNING! Recently I was student with the question: Would you asked "How do I become wise?" rather be wise, rich or happy? Many Immediately, I thought of two people would immediately respond, things. First, the old adage: Don't say "Happy" as our society so often anything and be thought a fool rather reinforces the idea "as long as he/she's than open your mouth and remove all happy." However, those who would take doubt!" So, I did the wise thing. I kept a few moments to think would invariably my mouth shut. respond, "Wise!" My second thought was more Why? If one is wise he can figure productive. -

Instructor's Guide for Torah Live's

SPONSORED BY STUART & STEPHANIE RONSON TO PERPETUATE THE MEMORY OF BETTY & MAURICE BIRNBAUM & ESTA & JACK RONSON Instructor’s Guide for Torah Live’s Sabbath The Ultimate Treasure Part 2 Version 1.2 “It is rare to see talent of this order used to so high and holy a cause. Rabbi Roth’s inspirational videos are outstanding. Will unlock the doors of learning to many.” — Chief Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks SABBATH: The Ultimate Treasure Sponsored by Stuart & Stephanie Ronson To Perpetuate the Memory of Betty & Maurice Birnbaum and Esta & Jack Ronson Instructors’ Guide for Torah Lives Sabbath: The Ultimate Treasure Part 2 Version 1.2 2 Thank you ......................................................................................................................4 Instructions.....................................................................................................................5 Latest Version ............................................................................................................5 Screen Resolution ......................................................................................................5 Pointer........................................................................................................................5 Lesson Plan ................................................................................................................6 Navigation..................................................................................................................6 Settings Page..............................................................................................................7