Title EMPAAKO "PRAISE NAMES" : an HISTORICAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping Uganda's Social Impact Investment Landscape

MAPPING UGANDA’S SOCIAL IMPACT INVESTMENT LANDSCAPE Joseph Kibombo Balikuddembe | Josephine Kaleebi This research is produced as part of the Platform for Uganda Green Growth (PLUG) research series KONRAD ADENAUER STIFTUNG UGANDA ACTADE Plot. 51A Prince Charles Drive, Kololo Plot 2, Agape Close | Ntinda, P.O. Box 647, Kampala/Uganda Kigoowa on Kiwatule Road T: +256-393-262011/2 P.O.BOX, 16452, Kampala Uganda www.kas.de/Uganda T: +256 414 664 616 www. actade.org Mapping SII in Uganda – Study Report November 2019 i DISCLAIMER Copyright ©KAS2020. Process maps, project plans, investigation results, opinions and supporting documentation to this document contain proprietary confidential information some or all of which may be legally privileged and/or subject to the provisions of privacy legislation. It is intended solely for the addressee. If you are not the intended recipient, you must not read, use, disclose, copy, print or disseminate the information contained within this document. Any views expressed are those of the authors. The electronic version of this document has been scanned for viruses and all reasonable precautions have been taken to ensure that no viruses are present. The authors do not accept responsibility for any loss or damage arising from the use of this document. Please notify the authors immediately by email if this document has been wrongly addressed or delivered. In giving these opinions, the authors do not accept or assume responsibility for any other purpose or to any other person to whom this report is shown or into whose hands it may come save where expressly agreed by the prior written consent of the author This document has been prepared solely for the KAS and ACTADE. -

Lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION of UGANDA

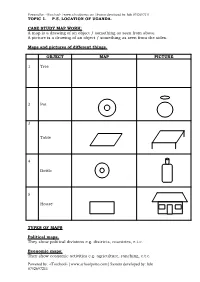

Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION OF UGANDA. CASE STUDY MAP WORK: A map is a drawing of an object / something as seen from above. A picture is a drawing of an object / something as seen from the sides. Maps and pictures of different things. OBJECT MAP PICTURE 1 Tree 2 Pot 3 Table 4 Bottle 5 House TYPES OF MAPS Political maps. They show political divisions e.g. districts, countries, e.t.c. Economic maps: They show economic activities e.g. agriculture, ranching, e.t.c. Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Physical maps; They show landforms e.g. mountains, rift valley, e.t.c. Climate maps: They give information on elements of climate e.g. rainfall, sunshine, e.t.c Population maps: They show population distribution. Importance of maps: i. They store information. ii. They help travellers to calculate distance between places. iii. They help people find way in strange places. iv. They show types of relief. v. They help to represent features Elements / qualities of a map: i. A title/ Heading. ii. A key. iii. Compass. iv. A scale. Importance elements of a map: Title/ heading: It tells us what a map is about. Key: It helps to interpret symbols used on a map or it shows the meanings of symbols used on a map. Main map symbols and their meanings S SYMBOL MEANING N 1 Canal 2 River 3 Dam 4 Waterfall Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Railway line 5 6 Bridge 7 Hill 8 Mountain peak 9 Swamp 10 Permanent lake 11 Seasonal lake A seasonal river 12 13 A quarry Importance of symbols. -

Tooro Kingdom 2 2

ClT / CIH /ITH 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 0090400007 I Le I 09 MAl 2012 NOMINATION OF EMPAAKO TRADITION FOR W~~.~.Q~~}~~~~.P?JIPNON THE LIST OF INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE IN NEED OF URGENT SAFEGUARDING 2012 DOCUMENTS OF REQUEST FROM STAKEHOLDERS Documents Pages 1. Letter of request form Tooro Kingdom 2 2. Letter of request from Bunyoro Kitara Kingdom 3 3. Statement of request from Banyabindi Community 4 4. Statement of request from Batagwenda Community 9 5. Minute extracts /resolutions from local government councils a) Kyenjojo District counciL 18 b) Kabarole District Council 19 c) Kyegegwa District Council 20 d) Ntoroko District Council 21 e) Kamwenge District Council 22 6. Statement of request from Area Member of Ugandan Parliament 23 7. Letters of request from institutions, NOO's, Associations & Companies a) Kabarole Research & Resource Centre 24 b) Mountains of the Moon University 25 c) Human Rights & Democracy Link 28 d) Rural Association Development Network 29 e) Modrug Uganda Association Ltd 34 f) Runyoro - Rutooro Foundation 38 g) Joint Effort to Save the Environment (JESE) .40 h) Foundation for Rural Development (FORUD) .41 i) Centre of African Christian Studies (CACISA) 42 j) Voice of Tooro FM 101 43 k) Better FM 44 1) Tooro Elders Forum (Isaazi) 46 m) Kibasi Elders Association 48 n) DAJ Communication Ltd 50 0) Elder Adonia Bafaaki Apuuli (Aged 94) 51 8. Statements of Area Senior Cultural Artists a) Kiganlbo Araali 52 b) Master Kalezi Atwoki 53 9. Request Statement from Students & Youth Associations a) St. Leo's College Kyegobe Student Cultural Association 54 b) Fort Portal Institute of Commerce Student's Cultural Association 57 c) Fort Portal School of Clinical Officers Banyoro, Batooro Union 59 10. -

Wildlife and Spiritual Knowledge at the Edge of Protected Areas: Raising Another Voice in Conservation Sarah Bortolamiol1,2,3,4,5*; Sabrina Krief1,3; Colin A

RESEARCH ARTICLE Ethnobiology and Conservation 2018, 7:12 (07 September 2018) doi:10.15451/ec2018-08-7.12-1-26 ISSN 22384782 ethnobioconservation.com Wildlife and spiritual knowledge at the edge of protected areas: raising another voice in conservation Sarah Bortolamiol1,2,3,4,5*; Sabrina Krief1,3; Colin A. Chapman5; Wilson Kagoro6; Andrew Seguya6; Marianne Cohen7 ABSTRACT International guidelines recommend the integration of local communities within protected areas management as a means to improve conservation efforts. However, local management plans rarely consider communities knowledge about wildlife and their traditions to promote biodiversity conservation. In the Sebitoli area of Kibale National Park, Uganda, the contact of local communities with wildlife has been strictly limited at least since the establishment of the park in 1993. The park has not develop programs, outside of touristic sites, to promote local traditions, knowledge, and beliefs in order to link neighboring community members to nature. To investigate such links, we used a combination of semidirected interviews and participative observations (N= 31) with three communities. While human and wildlife territories are legally disjointed, results show that traditional wildlife and spiritual related knowledge trespasses them and the contact with nature is maintained though practice, culture, and imagination. More than 66% of the people we interviewed have wild animals as totems, and continue to use plants to medicate, cook, or build. Five spirits structure humanwildlife relationships at specific sacred sites. However, this knowledge varies as a function of the location of local communities and the sacred sites. A better integration of local wildlifefriendly knowledge into management plans may revive communities’ connectedness to nature, motivate conservation behaviors, and promote biodiversity conservation. -

Traditional Cultural Institutions on Customary Practices in Uganda, In: Africa Spectrum, 49, 3, 29-54

Africa Spectrum Quinn, Joanna R. (2014), Tradition?! Traditional Cultural Institutions on Customary Practices in Uganda, in: Africa Spectrum, 49, 3, 29-54. URN: http://nbn-resolving.org/urn/resolver.pl?urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-4-7811 ISSN: 1868-6869 (online), ISSN: 0002-0397 (print) The online version of this and the other articles can be found at: <www.africa-spectrum.org> Published by GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies, Institute of African Affairs in co-operation with the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation Uppsala and Hamburg University Press. Africa Spectrum is an Open Access publication. It may be read, copied and distributed free of charge according to the conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. To subscribe to the print edition: <[email protected]> For an e-mail alert please register at: <www.africa-spectrum.org> Africa Spectrum is part of the GIGA Journal Family which includes: Africa Spectrum ●● Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs ●● Journal of Politics in Latin America <www.giga-journal-family.org> Africa Spectrum 3/2014: 29-54 Tradition?! Traditional Cultural Institutions on Customary Practices in Uganda Joanna R. Quinn Abstract: This contribution traces the importance of traditional institu- tions in rehabilitating societies in general terms and more particularly in post-independence Uganda. The current regime, partly by inventing “traditional” cultural institutions, partly by co-opting them for its own interests, contributed to a loss of legitimacy of those who claim respon- sibility for customary law. More recently, international prosecutions have complicated the use of customary mechanisms within such societies. -

Monolingualism Via Multilingualism: a Case Study of Language Use in the West Ugandan Town of Hoima

African Study Monographs, 34 (1): 1–25, March 2013 1 MONOLINGUALISM VIA MULTILINGUALISM: A CASE STUDY OF LANGUAGE USE IN THE WEST UGANDAN TOWN OF HOIMA Shigeki KAJI Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University ABSTRACT Multilingualism is one of the most salient features of language use in Africa and, at first sight, Uganda appears to be just one example of this practice. However, as Uganda has no lingua franca that is widely used by its entire population, questions about how people cope with multilingualism arise. Answers to such questions can be found in the fact that people are able to create a monolingual state in a given area because everyone is multilingual. That is, people speak their own language in their own domain and speak other peoples’ languages when they go to the latter’s domains. This conclusion emerged from interviews conducted with 100 inhabitants of Hoima city in western Uganda, an area primarily inhabited by the Nyoro people. The linguistic situation in Hoima provides a valuable case study of what can happen in the absence of a fully developed lingua franca and can contribute to broader discussions of language use in Africa. Key Words: Lingua franca; Multilingualism; Hoima; Nyoro; Uganda. INTRODUCTION I have conducted linguistic research in Uganda since 2001. The main themes of my research relate to the grammatical and lexical characteristics of little-known languages in the area. In the course of research, however, I noticed differences between the use of language in Uganda and that in the regions where I had studied before. -

Tribes” to “Regions”;

revista de recerca i formació en antropologia perifèria Número 20 (2), diciembre 2015 revistes.uab.cat/periferia From “tribes” to “regions”; Ethnicity and musical identity in Western Uganda Linda Cimardi1-University of Bologna DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.5565/rev/periferia.478 Abstract This article looks at how the paradigm of ethnicity in Uganda has influenced the conception and perception of cultural identity, and specifically of music identity. According to the 2002 Census, Uganda counts more than 50 different peoples within its territory. For most of these, the language spoken locally and the complex of musics and dances characterize their identity. These elements are currently fostered by the Government also by promoting annually a national festival where each area presents, among other items, its own music and dance repertoires. The structure of the present school festival intends to follow historical and cultural sedimentations (identifying “regions”), but it can still be tracedto the colonial classification of peoples (“tribes”). Considering data especially from western Uganda, the intermingling of the paradigm of ethnicity with the ones of music representativeness and identity will be observed. Discussion will consider the repertoires chosen for representativeness in the national context and concentrate on the ambiguity of the ethnic uniqueness of these musics and on the possibilities of expression of minorities. Key words: ethnicity, music, Uganda. Resumen El presente artículo trata de cómo el paradigma de la etnicidad ha influenciado el concepto y la percepción de la cultura identitaria, y específicamente de la música. De acuerdo con el censo realizado en el año 2002, Ugandacuenta con más de 50 tipos diferentes de pueblos dentro de su territorio. -

A Case of Tooro, Western Uganda

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 6 Issue 6||June. 2017 || PP.11-21 Pre- and Colonial Influence on Work Ethics of Africans: A Case of Tooro, Western Uganda Doris K. Kaije, Abstract: The study was aimed at tracing the evolution of work ethics in Tooro Society from pre-colonial to post-independence time, as guided by the following objectives: to identify the work ethics of the people in Tooro, explain the different reasons for working in the pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial era in Tooro society, and establish how influential colonialism was on the work ethics of the people in Tooro. The survey research design and specifically qualitative methods were used on the local people aged above forty five years. The study established that, work ethics of the indigenous people of Tooro were imbedded in taboos, proverbs, customs, tales, and stories. Tremendous changes have taken place in the traditional work ethics since the colonial era which introduced terms and conditions of work, contradicting with Tooro values and purpose of work. While pre-colonial purpose of work targeted society welfare, colonialism introduced new civilization and monitory economy which targeted individuals hence changing the work ethics among the Batooro. Conclusively, the post- colonial Tooro work ethics which continued to post-independence is a hybrid of both pre- colonial and colonial era. Therefore there is need to uphold good work ethics of the Batooro which made work meaningful to everybody, but also respect the introduced terms and conditions of work in order to reduce on redundancy of a section of the population. -

Fort Portal City Walk (9.341 Km)

Fort Portal - City walk Introduction The purpose of the tour is to see different facets of Fort Portal, both the more recognized and historical features as well as informal town life. This guide provides directions and a description of 30 sites. Feel free to follow your own rhythm and interest. If you explore every location, 8 hours might not be enough. If you limit yourself to walking, 4 hours will be sufficient. Total distance is 9.3 km. * The sites are not marked in order to avoid cluttering the map. The directions starts from the entrance of Rwenzori View Guesthouse, but you can start anywhere by taking a motorcycle taxi to a listed site. * If you get lost, do not ask people to show directions on the map. That will not work. Just ask a passer-by the name of the place you want to go and try to follow their verbal directions. * You can visit the sites listed in this guide. If needed, explain who you are and your interest to anybody around. Engage in some informal talk, and all will be fine. People like to chat and joke. Good-natured and simple responses and exchanges will keep everybody happy. If someone asks an awkward question (e.g., what is your salary, do you want a boy/girl friend), just smile and say you need to move on and do so. * If anything catches your eye, feel free to look and explore. People standing nearby might approach you, wondering what the foreigner is looking at. Just explain while smiling. -

P.6 SST CLASSWORK WEEK TWO Monday 8Th June, 2020

Plot 48 Muwaire Rd (behind IHK Hospital) P.O.BOX 5337, KAMPALA - UGANDA Tel: 256783111908 Email: [email protected] Website: www.stagnes.co.ug P.6 SST CLASSWORK WEEK TWO Monday 8th June, 2020. MIGRATION PATTERNS IN EAST AFRICA 1. What is migration? -Migration is the movement of people from one place to another looking for better settlement. Why do people move to different places today? Looking for better jobs. Looking for better social services. Looking for better fertile soil for crop growing. Shortage of pasture and water for their animals. Shortage of land due to over population. Internal and external conflicts. Famine due to prolonged drought in some areas. Types of migration today. Rural-urban migration Urban-rural migration Urban-urban migration Rural-rural migration 2. What is Rural - urban migration? Rural- urban migration is the movement of people from villages to towns for better settlement. 3. What is urban - urban migration? Urban - urban migration is the movement of people from one town to another town looking for better settlement. 4. What is Rural - rural migration? Rural - rural migration is the movement of people from one village to another looking for better settlement. Activity 1. What is migration? 2. Give two reasons for the migration of ethnic groups into East Africa. 3. Mention two reasons why people migrate today. 4. State two problems people face while migrating. 5. What is urban – rural migration? Tuesday 9th June, 2020. Causes of Rural- urban migration To get better jobs in towns. To get better social services in towns To enjoy better entertainment in towns To escape cultural practices in villages Dangers Caused by rural- urban migration. -

A History of the Heritage Economy in Yoweri Museveni's Uganda

Journal of Eastern African Studies ISSN: 1753-1055 (Print) 1753-1063 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjea20 A history of the heritage economy in Yoweri Museveni’s Uganda Derek R. Peterson To cite this article: Derek R. Peterson (2016) A history of the heritage economy in Yoweri Museveni’s Uganda, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 10:4, 789-806, DOI: 10.1080/17531055.2016.1272297 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2016.1272297 Published online: 01 Feb 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjea20 Download by: [University of Cambridge] Date: 01 February 2017, At: 07:29 JOURNAL OF EASTERN AFRICAN STUDIES, 2016 VOL. 10, NO. 4, 789–806 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2016.1272297 A history of the heritage economy in Yoweri Museveni’s Uganda Derek R. Peterson Department of History, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY When the National Resistance Movement (NRM) came to power in Received 19 August 2016 1986, its cadres overflowed with reformist zeal. They set out to Accepted 9 December 2016 transform Uganda’s public life, put an end to ethnic division, and KEYWORDS promote local democracy. Today much of this reformist energy Yoweri Museveni; elections; has dissipated, and undemocratic kingdoms largely define the heritage; traditional cultural landscape. This essay attempts to explain how these medicine; Rwenzururu things came to pass. It argues that the heritage economy offered NRM officials and other brokers an ensemble of bureaucratic techniques with which to naturalize and standardize cultures. -

Traditional Cultural Institutions on Customary Practices Of

Tradition?! Traditional cultural institutions on Customary Practices in Uganda1 Joanna R. Quinn2 Working paper. Please do not cite without permission. Transitional justice is concerned with how societies move from conflict to peace or from authoritarian regimes to democracy—by dealing with the resulting questions of justice and social healing. Among the “tools” that theorists and practitioners of transitional justice have at their disposal in restoring social cohesion after conflict are customary methods of acknowledgement. While such practices have not yet become part of the mainstream, in as much as truth commissions and tribunals have, evidence of their utility in several societies is beginning to appear. The use of these traditional practices of acknowledgement in Uganda is widespread. Each of the 56 different ethnic groups across the country has at some point relied on such practices. This paper explores the attitudes of the leaders of the newly-restored traditional cultural institutions toward these practices. It further assesses the agency of traditional cultural institutions in their use. This analysis is carried out in the context of the ever-turbulent political situation in Uganda, and of the sordid legacy of conflict in that country. 1 A paper prepared for presentation at the Annual Convention of the International Studies Association, 16 Feb. 2009, New York, USA. Research for this project was carried out with assistance from the United States Institute of Peace (SG-135-05F), with research assistance from Stéphanie Anne-Gaëlle Vieille. 2 Joanna R. Quinn is Assistant Professor of Political Science and Co-Director of the Nationalism and Ethnic Conflict Research Group at The University of Western Ontario.