Pdf | 15.81 Mb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insurance Regulatory Authority of Uganda Licensed Insurance Brokers for the Year 2019

INSURANCE REGULATORY AUTHORITY OF UGANDA LICENSED INSURANCE BROKERS FOR THE YEAR 2019 1. Abacus Insurance Brokers (U) Ltd. 21. Interlink Insurance (Africa) Ltd 3rd Floor, East African Chains Plot 855 Mawanda Road, Kamwokya Plot 3, 2nd Industrial Area P.O. Box 21086 P.O. Box 50 KAMPALA KAMPALA Tel. 256-392 174954/5/0772433832 Tel. 0312-265681 0312-265440) E-mail: [email protected] 0312-265680 Fax 0312-265410 [email protected]; [email protected] www.abacusinsurers.com 2. African Risk & Insurance Services 22. Interstate Insurance Services Ltd. (ARIS) Plot No. 4, Flat No. 1 Plot 88, luthuri Avenue Kimathi Avenue P O Box 75457 Opposite Kampala Casino KAMPALA P.O. Box 4999 Tel: 0713-433636/0392-893472 KAMPALA /0754-010012 Tel. 0414-258275 Fax 0414-235126 [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] 3. Afrisafe Risk Consultants Ltd 23. Kiboko Financial Services Ltd Plot 7, Bandari Rise Bugoloobi Kiboko House, Coronation Avenue, P O Box 37034 Plot No. 288, 328, 348 KAMPALA UMA Show Grounds, Lugogo Ground Floor, Redstone House P O Box 31376 KAMPALA Email:[email protected] Tel. 0417-100900/ 0312-310900 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Website: www.kibokogroup.com 4. Assured Partners Insurance Broker 24. Legacy Insurance Services Ltd Plot 18, Kintu Road Plot 24/26 Entebbe Road Imperial Royal Apartment A1 Shri Ganesh Plaza Level 2 Suite 4 & 5 P.O. Box 11605 P O Box 26476KAMPALA KAMPALA Email: [email protected] Tel. 0414581666/256-777111011 [email protected] [email protected] Tel. -

Risk Factors for Measles Death Among Children in Kyegegwa District – Measles Outbreak in Kyegegwa District

Public Health Fellowship Program – Field Epidemiology Track My Fellowship Achievements Mafigiri Richardson, BSc Zoo/Chem, MSc IIDM Fellow, cohort 2015 Host site, Rakai District . Mission – To serve community through a transparent & coordinated delivery of service which focus on national, local priority and contribute to improvement in quality of life of people in Rakai District . Mandate – To provide health services through a decentralized system 2 My Fellowship achievements Response to Public Health Emergencies . Led outbreaks; – Risk factors for measles death among children in Kyegegwa district – Measles outbreak in Kyegegwa district . Participated in; . Suspected food poisoning among primary school pupils, Namutumba Dist. A large typhoid outbreak in Kampala, 2015 . Suspected bleeding disease, Hoima & Buliisa districts 3 My Fellowship achievements Epidemiological study . Under five mortality and household sanitary practices in Kakuuto County Rakai District, April 1st, 2014-March 30th, 2016 4 My Fellowship achievements Public health surveillance . Analysis of public health surveillance data on neonatal and perinatal mortality in Rakai District . Typhoid verification in Lyantonde and Rakai districts 5 My Fellowship achievements Scientific Communication . HIV Prevalence among Youths & Services Uptake in Kasensero, 1st NAHC & NFEC . Risk factors for measles death in children, Kyegegwa District, AFENET & NFEC . Diarrheal diseases mortality in U5 & household sanitary practices in Kakuuto County, Rakai District-NFEC 6 My Fellowship achievements Scientific Communication-Main Author . HIV Prevalence and Uptake of HIV Services among Youth (15-24 Years) in Fishing and Neighboring Communities of Kasensero, Rakai District (BMC Public health) . Risk Factors for Measles Death in Children: Kyegegwa District (BMC Infectious diseases) 7 My Fellowship achievements Scientific Communication, Co-Author . Suspected Bleeding Illness in Hoima and Surrounding Districts, 2016 (Plos One) . -

Strengthening Climate Resilience Through Integration of Climate

Strengthening Climate Resilience through Integration of Climate Change, Women and Youth Issues in Uganda’s Agriculture Sector Analysis of Agriculture Related Policies and Programmes ACODE Policy Research Paper Series No.95, 2019 Supported by Strengthening Climate Resilience through Integration of Climate Change, Women and Youth Issues in Uganda’s Agriculture Sector Analysis of Agriculture Related Policies and Programmes ACODE Policy Research Paper Series No.95, 2019 Published by ACODE P. O. Box 29836, Kampala Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Website: https://www.acode-u.org Citation: Advocates Coalition for Development and Environment. (2019). Strengthening Climate Resilience through Integration of Climate Change, Women and Youth Issues in Uganda’s Agriculture Sector: Analysis of Agriculture Related Policies and Programmes, Kampala: ACODE. Policy Research Paper Series No.95. © ACODE 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. ACODE policy work is supported by generous donations and grants from bilateral donors and charitable foundations. Reproduction or use of this publication for academic or charitable purposes or for purposes of informing public policy is excluded from this restriction. ISBN: 978 9970 567 14 0 Cover: A farmer tending to her vegetable garden. Credit Observer Media, July 2018 Strengthening Climate Resilience through integration of Climate Change, Women & Youth issues in Uganda’s Agriculture Sector Acknowledgements The study from which this publication was produced would not have been possible without both financial and technical support. -

Retrospective Evaluation of Interventions for Handling Psychological Trauma in Families Affected by the July 11, 2010 Terror Attacks in Kampala

RETROSPECTIVE EVALUATION OF INTERVENTIONS FOR HANDLING PSYCHOLOGICAL TRAUMA IN FAMILIES AFFECTED BY THE JULY 11, 2010 TERROR ATTACKS IN KAMPALA JACOB WAISWA, 2010/HD03/2962U BCP MAKERERE UNIVERSITY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DIRECTORATE OF RESEARCH AND GRADUATE TRAINING IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MASTERS OF ARTS IN PEACE AND CONFLICT STUDIES DEGREE OF MAKERERE UNIVERSITY JUNE 2014 DECLARATION This study is original and has not been submitted for any other degree award to any other university before. Signed: ……………... Jacob Waiswa Date: ……………… ii APPROVAL This dissertation entitled, ―Retrospective Evaluation of Interventions for Handling Psychological Trauma in Families Affected by the July 11, 2010 Terror Attacks in Kampala‖ by JACOB WAISWA was submitted to the directorate of research and graduate training for examinations with my approval as the academic supervisor for the award of a Masters of Arts Degree in Peace and Conflict Studies. Signed: ……….…………….. Prof. Peter Baguma Academic Supervisor iii DEDICATION I dedicate this book to my mother, Daisy Namulemo, for the relentless support she offered me; and my sisters, Rachael Babirye and Regina Kiiza, whose life conditions drove me to consider a mental health study on top of the fact that I came from the same academic background (mental health). Together we shall win. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I salute all victims of the July 11th, 2010 terror attacks for accepting to open up to me and for their time during the research data collection. To some, it was challenging to speak to me as it always came with terrifying memories, sadness, and tears, more so, me being a stranger to them. -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

Mapping Uganda's Social Impact Investment Landscape

MAPPING UGANDA’S SOCIAL IMPACT INVESTMENT LANDSCAPE Joseph Kibombo Balikuddembe | Josephine Kaleebi This research is produced as part of the Platform for Uganda Green Growth (PLUG) research series KONRAD ADENAUER STIFTUNG UGANDA ACTADE Plot. 51A Prince Charles Drive, Kololo Plot 2, Agape Close | Ntinda, P.O. Box 647, Kampala/Uganda Kigoowa on Kiwatule Road T: +256-393-262011/2 P.O.BOX, 16452, Kampala Uganda www.kas.de/Uganda T: +256 414 664 616 www. actade.org Mapping SII in Uganda – Study Report November 2019 i DISCLAIMER Copyright ©KAS2020. Process maps, project plans, investigation results, opinions and supporting documentation to this document contain proprietary confidential information some or all of which may be legally privileged and/or subject to the provisions of privacy legislation. It is intended solely for the addressee. If you are not the intended recipient, you must not read, use, disclose, copy, print or disseminate the information contained within this document. Any views expressed are those of the authors. The electronic version of this document has been scanned for viruses and all reasonable precautions have been taken to ensure that no viruses are present. The authors do not accept responsibility for any loss or damage arising from the use of this document. Please notify the authors immediately by email if this document has been wrongly addressed or delivered. In giving these opinions, the authors do not accept or assume responsibility for any other purpose or to any other person to whom this report is shown or into whose hands it may come save where expressly agreed by the prior written consent of the author This document has been prepared solely for the KAS and ACTADE. -

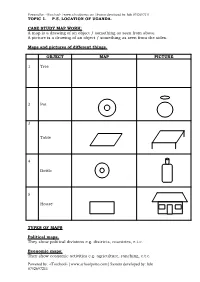

Lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION of UGANDA

Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION OF UGANDA. CASE STUDY MAP WORK: A map is a drawing of an object / something as seen from above. A picture is a drawing of an object / something as seen from the sides. Maps and pictures of different things. OBJECT MAP PICTURE 1 Tree 2 Pot 3 Table 4 Bottle 5 House TYPES OF MAPS Political maps. They show political divisions e.g. districts, countries, e.t.c. Economic maps: They show economic activities e.g. agriculture, ranching, e.t.c. Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Physical maps; They show landforms e.g. mountains, rift valley, e.t.c. Climate maps: They give information on elements of climate e.g. rainfall, sunshine, e.t.c Population maps: They show population distribution. Importance of maps: i. They store information. ii. They help travellers to calculate distance between places. iii. They help people find way in strange places. iv. They show types of relief. v. They help to represent features Elements / qualities of a map: i. A title/ Heading. ii. A key. iii. Compass. iv. A scale. Importance elements of a map: Title/ heading: It tells us what a map is about. Key: It helps to interpret symbols used on a map or it shows the meanings of symbols used on a map. Main map symbols and their meanings S SYMBOL MEANING N 1 Canal 2 River 3 Dam 4 Waterfall Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Railway line 5 6 Bridge 7 Hill 8 Mountain peak 9 Swamp 10 Permanent lake 11 Seasonal lake A seasonal river 12 13 A quarry Importance of symbols. -

Funding Going To

% Funding going to Funding Country Name KP‐led Timeline Partner Name Sub‐awardees SNU1 PSNU MER Structural Interventions Allocated Organizations HTS_TST Quarterly stigma & discrimination HTS_TST_NEG meetings; free mental services to HTS_TST_POS KP clients; access to legal services PrEP_CURR for KP PLHIV PrEP_ELIGIBLE Centro de Orientacion e PrEP_NEW Dominican Republic $ 1,000,000.00 88.4% MOSCTHA, Esperanza y Caridad, MODEMU Region 0 Distrito Nacional Investigacion Integral (COIN) PrEP_SCREEN TX_CURR TX_NEW TX_PVLS (D) TX_PVLS (N) TX_RTT Gonaives HTS_TST KP sensitization focusing on Artibonite Saint‐Marc HTS_TST_NEG stigma & discrimination, Nord Cap‐Haitien HTS_TST_POS understanding sexual orientation Croix‐des‐Bouquets KP_PREV & gender identity, and building Leogane PrEP_CURR clinical providers' competency to PrEP_CURR_VERIFY serve KP FY19Q4‐ KOURAJ, ACESH, AJCCDS, ANAPFEH, APLCH, CHAAPES, PrEP_ELIGIBLE Haiti $ 1,000,000.00 83.2% FOSREF FY21Q2 HERITAGE, ORAH, UPLCDS PrEP_NEW Ouest PrEP_NEW_VERIFY Port‐au‐Prince PrEP_SCREEN TX_CURR TX_CURR_VERIFY TX_NEW TX_NEW_VERIFY Bomu Hospital Affiliated Sites Mombasa County Mombasa County not specified HTS_TST Kitui County Kitui County HTS_TST_NEG CHS Naishi Machakos County Machakos County HTS_TST_POS Makueni County Makueni County KP_PREV CHS Tegemeza Plus Muranga County Muranga County PrEP_CURR EGPAF Timiza Homa Bay County Homa Bay County PrEP_CURR_VERIFY Embu County Embu County PrEP_ELIGIBLE Kirinyaga County Kirinyaga County HWWK Nairobi Eastern PrEP_NEW Tharaka Nithi County Tharaka Nithi County -

Nakawa Division Grades

DIVISION PARISH VILLAGE STREET AREA GRADE NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO24 LUTHULI 4TH CLOSE 2-9 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO25 LUTHULI 1ST CLOSE 1-9 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO26 LUTHULI 5TH CLOSE 1-9 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO27 LUTHULI 2ND CLOSE 1-10 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO28 LUTHULI RISE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II MBUYA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II MIZINDALO ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II MPANGA CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II MUZIWAACO ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II PRINCESS ANNE DRIVE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II ROBERT MUGABE ROAD. 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II BAZARRABUSA DRIVE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II BINAYOMBA RISE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II BINAYOMBA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II BUGOLOBI STREET 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II FARADAY ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II FARADY ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II HUNTER CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II KULUBYA CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I BANDALI RISE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I HANLON ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I MUWESI ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I NYONDO CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I SALMON RISE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I SPRING ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I YOUNGER AVENUE 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I KALONDA KISASI ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I KALONDA SERUMAGA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I MUKALAZI KISASI ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I MUKALAZI MUKALAZI ROAD 1 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I MULIMIRA OFF MOYO CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I NTINDA- OLD KIRA ZONE NTINDA- OLD KIRA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I OLD KIRA ROAD BATAKA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I OLD KIRA ROAD LUTAYA -

Tooro Kingdom 2 2

ClT / CIH /ITH 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 0090400007 I Le I 09 MAl 2012 NOMINATION OF EMPAAKO TRADITION FOR W~~.~.Q~~}~~~~.P?JIPNON THE LIST OF INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE IN NEED OF URGENT SAFEGUARDING 2012 DOCUMENTS OF REQUEST FROM STAKEHOLDERS Documents Pages 1. Letter of request form Tooro Kingdom 2 2. Letter of request from Bunyoro Kitara Kingdom 3 3. Statement of request from Banyabindi Community 4 4. Statement of request from Batagwenda Community 9 5. Minute extracts /resolutions from local government councils a) Kyenjojo District counciL 18 b) Kabarole District Council 19 c) Kyegegwa District Council 20 d) Ntoroko District Council 21 e) Kamwenge District Council 22 6. Statement of request from Area Member of Ugandan Parliament 23 7. Letters of request from institutions, NOO's, Associations & Companies a) Kabarole Research & Resource Centre 24 b) Mountains of the Moon University 25 c) Human Rights & Democracy Link 28 d) Rural Association Development Network 29 e) Modrug Uganda Association Ltd 34 f) Runyoro - Rutooro Foundation 38 g) Joint Effort to Save the Environment (JESE) .40 h) Foundation for Rural Development (FORUD) .41 i) Centre of African Christian Studies (CACISA) 42 j) Voice of Tooro FM 101 43 k) Better FM 44 1) Tooro Elders Forum (Isaazi) 46 m) Kibasi Elders Association 48 n) DAJ Communication Ltd 50 0) Elder Adonia Bafaaki Apuuli (Aged 94) 51 8. Statements of Area Senior Cultural Artists a) Kiganlbo Araali 52 b) Master Kalezi Atwoki 53 9. Request Statement from Students & Youth Associations a) St. Leo's College Kyegobe Student Cultural Association 54 b) Fort Portal Institute of Commerce Student's Cultural Association 57 c) Fort Portal School of Clinical Officers Banyoro, Batooro Union 59 10. -

Wildlife and Spiritual Knowledge at the Edge of Protected Areas: Raising Another Voice in Conservation Sarah Bortolamiol1,2,3,4,5*; Sabrina Krief1,3; Colin A

RESEARCH ARTICLE Ethnobiology and Conservation 2018, 7:12 (07 September 2018) doi:10.15451/ec2018-08-7.12-1-26 ISSN 22384782 ethnobioconservation.com Wildlife and spiritual knowledge at the edge of protected areas: raising another voice in conservation Sarah Bortolamiol1,2,3,4,5*; Sabrina Krief1,3; Colin A. Chapman5; Wilson Kagoro6; Andrew Seguya6; Marianne Cohen7 ABSTRACT International guidelines recommend the integration of local communities within protected areas management as a means to improve conservation efforts. However, local management plans rarely consider communities knowledge about wildlife and their traditions to promote biodiversity conservation. In the Sebitoli area of Kibale National Park, Uganda, the contact of local communities with wildlife has been strictly limited at least since the establishment of the park in 1993. The park has not develop programs, outside of touristic sites, to promote local traditions, knowledge, and beliefs in order to link neighboring community members to nature. To investigate such links, we used a combination of semidirected interviews and participative observations (N= 31) with three communities. While human and wildlife territories are legally disjointed, results show that traditional wildlife and spiritual related knowledge trespasses them and the contact with nature is maintained though practice, culture, and imagination. More than 66% of the people we interviewed have wild animals as totems, and continue to use plants to medicate, cook, or build. Five spirits structure humanwildlife relationships at specific sacred sites. However, this knowledge varies as a function of the location of local communities and the sacred sites. A better integration of local wildlifefriendly knowledge into management plans may revive communities’ connectedness to nature, motivate conservation behaviors, and promote biodiversity conservation. -

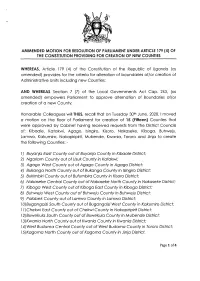

(4) of the Constitution Providing for Creation of New Counties

AMMENDED MOTTON FOR RESOLUTTON OF PARLTAMENT UNDER ARTTCLE 179 (4) OF THE CONSTITUTION PROVIDING FOR CREATION OF NEW COUNTIES WHEREAS, Ariicle 179 (a) of the Constitution of the Republic of Ugondo (os omended) provides for the criterio for olterotion of boundories oflor creotion of Administrotive Units including new Counties; AND WHEREAS Section 7 (7) of the Locql Governments Act Cop. 243, (os omended) empowers Porlioment to opprove olternotion of Boundories of/or creotion of o new County; Honoroble Colleogues willTHUS, recoll thot on Tuesdoy 30rn June, 2020,1 moved o motion on the floor of Porlioment for creotion of I5 (Fitteen) Counties thot were opproved by Cobinet hoving received requests from the District Councils of; Kiboole, Kotokwi, Agogo, lsingiro, Kisoro, Nokoseke, Kibogo, Buhweju, Lomwo, Kokumiro, Nokopiripirit, Mubende, Kwonio, Tororo ond Jinjo to creote the following Counties: - l) Buyanja Eost County out of Buyanjo County in Kibaale Distric[ 2) Ngoriom Covnty out of Usuk County in Kotakwi; 3) Agago Wesf County out of Agogo County in Agogo District; 4) Bukonga Norfh County out of Bukongo County in lsingiro District; 5) Bukimbiri County out of Bufumbira County in Kisoro District; 6) Nokoseke Centrol County out of Nokoseke Norfh County in Nokoseke Disfricf 7) Kibogo Wesf County out of Kibogo Eost County in Kbogo District; B) Buhweju West County aut of Buhweju County in Buhweju District; 9) Palobek County out of Lamwo County in Lamwo District; lA)BugongoiziSouth County out of BugongoiziWest County in Kokumiro Districf; I l)Chekwi Eosf County out of Chekwi County in Nokopiripirit District; l2)Buweku/o Soufh County out of Buweku/o County in Mubende Disfricf, l3)Kwanio Norfh County out of Kwonio Counfy in Kwonio Dislricf l )West Budomo Central County out of Wesf Budomo County inTororo Districf; l5)Kogomo Norfh County out of Kogomo County in Jinjo Districf.