Strengthening Climate Resilience Through Integration of Climate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Risk Factors for Measles Death Among Children in Kyegegwa District – Measles Outbreak in Kyegegwa District

Public Health Fellowship Program – Field Epidemiology Track My Fellowship Achievements Mafigiri Richardson, BSc Zoo/Chem, MSc IIDM Fellow, cohort 2015 Host site, Rakai District . Mission – To serve community through a transparent & coordinated delivery of service which focus on national, local priority and contribute to improvement in quality of life of people in Rakai District . Mandate – To provide health services through a decentralized system 2 My Fellowship achievements Response to Public Health Emergencies . Led outbreaks; – Risk factors for measles death among children in Kyegegwa district – Measles outbreak in Kyegegwa district . Participated in; . Suspected food poisoning among primary school pupils, Namutumba Dist. A large typhoid outbreak in Kampala, 2015 . Suspected bleeding disease, Hoima & Buliisa districts 3 My Fellowship achievements Epidemiological study . Under five mortality and household sanitary practices in Kakuuto County Rakai District, April 1st, 2014-March 30th, 2016 4 My Fellowship achievements Public health surveillance . Analysis of public health surveillance data on neonatal and perinatal mortality in Rakai District . Typhoid verification in Lyantonde and Rakai districts 5 My Fellowship achievements Scientific Communication . HIV Prevalence among Youths & Services Uptake in Kasensero, 1st NAHC & NFEC . Risk factors for measles death in children, Kyegegwa District, AFENET & NFEC . Diarrheal diseases mortality in U5 & household sanitary practices in Kakuuto County, Rakai District-NFEC 6 My Fellowship achievements Scientific Communication-Main Author . HIV Prevalence and Uptake of HIV Services among Youth (15-24 Years) in Fishing and Neighboring Communities of Kasensero, Rakai District (BMC Public health) . Risk Factors for Measles Death in Children: Kyegegwa District (BMC Infectious diseases) 7 My Fellowship achievements Scientific Communication, Co-Author . Suspected Bleeding Illness in Hoima and Surrounding Districts, 2016 (Plos One) . -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

Funding Going To

% Funding going to Funding Country Name KP‐led Timeline Partner Name Sub‐awardees SNU1 PSNU MER Structural Interventions Allocated Organizations HTS_TST Quarterly stigma & discrimination HTS_TST_NEG meetings; free mental services to HTS_TST_POS KP clients; access to legal services PrEP_CURR for KP PLHIV PrEP_ELIGIBLE Centro de Orientacion e PrEP_NEW Dominican Republic $ 1,000,000.00 88.4% MOSCTHA, Esperanza y Caridad, MODEMU Region 0 Distrito Nacional Investigacion Integral (COIN) PrEP_SCREEN TX_CURR TX_NEW TX_PVLS (D) TX_PVLS (N) TX_RTT Gonaives HTS_TST KP sensitization focusing on Artibonite Saint‐Marc HTS_TST_NEG stigma & discrimination, Nord Cap‐Haitien HTS_TST_POS understanding sexual orientation Croix‐des‐Bouquets KP_PREV & gender identity, and building Leogane PrEP_CURR clinical providers' competency to PrEP_CURR_VERIFY serve KP FY19Q4‐ KOURAJ, ACESH, AJCCDS, ANAPFEH, APLCH, CHAAPES, PrEP_ELIGIBLE Haiti $ 1,000,000.00 83.2% FOSREF FY21Q2 HERITAGE, ORAH, UPLCDS PrEP_NEW Ouest PrEP_NEW_VERIFY Port‐au‐Prince PrEP_SCREEN TX_CURR TX_CURR_VERIFY TX_NEW TX_NEW_VERIFY Bomu Hospital Affiliated Sites Mombasa County Mombasa County not specified HTS_TST Kitui County Kitui County HTS_TST_NEG CHS Naishi Machakos County Machakos County HTS_TST_POS Makueni County Makueni County KP_PREV CHS Tegemeza Plus Muranga County Muranga County PrEP_CURR EGPAF Timiza Homa Bay County Homa Bay County PrEP_CURR_VERIFY Embu County Embu County PrEP_ELIGIBLE Kirinyaga County Kirinyaga County HWWK Nairobi Eastern PrEP_NEW Tharaka Nithi County Tharaka Nithi County -

Tooro Kingdom 2 2

ClT / CIH /ITH 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 0090400007 I Le I 09 MAl 2012 NOMINATION OF EMPAAKO TRADITION FOR W~~.~.Q~~}~~~~.P?JIPNON THE LIST OF INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE IN NEED OF URGENT SAFEGUARDING 2012 DOCUMENTS OF REQUEST FROM STAKEHOLDERS Documents Pages 1. Letter of request form Tooro Kingdom 2 2. Letter of request from Bunyoro Kitara Kingdom 3 3. Statement of request from Banyabindi Community 4 4. Statement of request from Batagwenda Community 9 5. Minute extracts /resolutions from local government councils a) Kyenjojo District counciL 18 b) Kabarole District Council 19 c) Kyegegwa District Council 20 d) Ntoroko District Council 21 e) Kamwenge District Council 22 6. Statement of request from Area Member of Ugandan Parliament 23 7. Letters of request from institutions, NOO's, Associations & Companies a) Kabarole Research & Resource Centre 24 b) Mountains of the Moon University 25 c) Human Rights & Democracy Link 28 d) Rural Association Development Network 29 e) Modrug Uganda Association Ltd 34 f) Runyoro - Rutooro Foundation 38 g) Joint Effort to Save the Environment (JESE) .40 h) Foundation for Rural Development (FORUD) .41 i) Centre of African Christian Studies (CACISA) 42 j) Voice of Tooro FM 101 43 k) Better FM 44 1) Tooro Elders Forum (Isaazi) 46 m) Kibasi Elders Association 48 n) DAJ Communication Ltd 50 0) Elder Adonia Bafaaki Apuuli (Aged 94) 51 8. Statements of Area Senior Cultural Artists a) Kiganlbo Araali 52 b) Master Kalezi Atwoki 53 9. Request Statement from Students & Youth Associations a) St. Leo's College Kyegobe Student Cultural Association 54 b) Fort Portal Institute of Commerce Student's Cultural Association 57 c) Fort Portal School of Clinical Officers Banyoro, Batooro Union 59 10. -

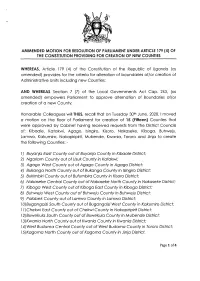

(4) of the Constitution Providing for Creation of New Counties

AMMENDED MOTTON FOR RESOLUTTON OF PARLTAMENT UNDER ARTTCLE 179 (4) OF THE CONSTITUTION PROVIDING FOR CREATION OF NEW COUNTIES WHEREAS, Ariicle 179 (a) of the Constitution of the Republic of Ugondo (os omended) provides for the criterio for olterotion of boundories oflor creotion of Administrotive Units including new Counties; AND WHEREAS Section 7 (7) of the Locql Governments Act Cop. 243, (os omended) empowers Porlioment to opprove olternotion of Boundories of/or creotion of o new County; Honoroble Colleogues willTHUS, recoll thot on Tuesdoy 30rn June, 2020,1 moved o motion on the floor of Porlioment for creotion of I5 (Fitteen) Counties thot were opproved by Cobinet hoving received requests from the District Councils of; Kiboole, Kotokwi, Agogo, lsingiro, Kisoro, Nokoseke, Kibogo, Buhweju, Lomwo, Kokumiro, Nokopiripirit, Mubende, Kwonio, Tororo ond Jinjo to creote the following Counties: - l) Buyanja Eost County out of Buyanjo County in Kibaale Distric[ 2) Ngoriom Covnty out of Usuk County in Kotakwi; 3) Agago Wesf County out of Agogo County in Agogo District; 4) Bukonga Norfh County out of Bukongo County in lsingiro District; 5) Bukimbiri County out of Bufumbira County in Kisoro District; 6) Nokoseke Centrol County out of Nokoseke Norfh County in Nokoseke Disfricf 7) Kibogo Wesf County out of Kibogo Eost County in Kbogo District; B) Buhweju West County aut of Buhweju County in Buhweju District; 9) Palobek County out of Lamwo County in Lamwo District; lA)BugongoiziSouth County out of BugongoiziWest County in Kokumiro Districf; I l)Chekwi Eosf County out of Chekwi County in Nokopiripirit District; l2)Buweku/o Soufh County out of Buweku/o County in Mubende Disfricf, l3)Kwanio Norfh County out of Kwonio Counfy in Kwonio Dislricf l )West Budomo Central County out of Wesf Budomo County inTororo Districf; l5)Kogomo Norfh County out of Kogomo County in Jinjo Districf. -

Sources and Causes of Maternal Deaths Among Obstetric Referrals to Fortportal Regional Referral Hospital Kabarole District, Uganda

SOURCES AND CAUSES OF MATERNAL DEATHS AMONG OBSTETRIC REFERRALS TO FORTPORTAL REGIONAL REFERRAL HOSPITAL KABAROLE DISTRICT, UGANDA. BY LOGOSE JOAN BMS/0075/133/DU A RESEARCH PROPOSAL SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CLINICAL MEDICINE AND DENTISTRY FOR THE AWARD OF A BACHELORS IN MEDICINE AND SUGERY AT KAMPALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY MARCH, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................. i DECLARATION ........................................................................................................................... iv APPROVAL ................................................................................................................................... v DEDICATION ............................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ...................................................................... vi OPERATIONAL DEFINITIONS ................................................................................................. vii CHAPTER ONE ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background .............................................................................................................................. -

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS SUPPLEMENT No. 5 3Rd February

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS SUPPLEMENT No. 5 3rd February, 2012 STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS SUPPLEMENT to The Uganda Gazette No. 7 Volume CV dated 3rd February, 2012 Printed by UPPC, Entebbe, by Order of the Government. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2012 No. 5. The Local Government (Declaration of Towns) Regulations, 2012. (Under sections 7(3) and 175(1) of the Local Governments Act, Cap. 243) In exercise of the powers conferred upon the Minister responsible for local governments by sections 7(3) and 175(1) of the Local Governments Act, in consultation with the districts and with the approval of Cabinet, these Regulations are made this 14th day of July, 2011. 1. Title These Regulations may be cited as the Local Governments (Declaration of Towns) Regulations, 2012. 2. Declaration of Towns The following areas are declared to be towns— (a) Amudat - consisting of Amudat trading centre in Amudat District; (b) Buikwe - consisting of Buikwe Parish in Buikwe District; (c) Buyende - consisting of Buyende Parish in Buyende District; (d) Kyegegwa - consisting of Kyegegwa Town Board in Kyegegwa District; (e) Lamwo - consisting of Lamwo Town Board in Lamwo District; - consisting of Otuke Town Board in (f) Otuke Otuke District; (g) Zombo - consisting of Zombo Town Board in Zombo District; 259 (h) Alebtong (i) Bulambuli (j) Buvuma (k) Kanoni (l) Butemba (m) Kiryandongo (n) Agago (o) Kibuuku (p) Luuka (q) Namayingo (r) Serere (s) Maracha (t) Bukomansimbi (u) Kalungu (v) Gombe (w) Lwengo (x) Kibingo (y) Nsiika (z) Ngora consisting of Alebtong Town board in Alebtong District; -

Performance Snapshot Kyaka II Q1 2021 Draft

Performance Snapshot Quarter 1 Uganda Refugee Response Plan (RRP) 2020-2021 January - March 2021 124,712 Kyaka II Refugee Settlement Refugees & Asylum Seekers 33 Partners 40,798 HHs Mbarara Sub-Office Sector Actual status per key indicator Target/Standard (21’) Actual against annual target or standard 67% children of school going age 100% 67% 33% enrolled in primary school (Term 1 2020) 0 20 40 60 80 100 The pupil teacher ratio for primary Actual schools was 1:80 (Term 1 2020) 1:71 Education Target 0 21 42 63 84 105 # 0 households using alternative 24,719 (target) 0 0% 20 40 60 80 100 and/or renewable energy (Q1 data) 1/HH (standard) 0 hectares of forests, wetlands, Environment & riverbanks and lakeshores protected 0 20 40 60 80 100 Energy 206 ha 0% and restored (Q1 data) 107,105 refugees receiving food 124,712 Individuals 86% assistance through cash transfers 0 20 40 60 80 100 (in Q1) 58.1% of HH with poor or borderline 17% Food Food Consumption Score (in Q1) <20% (standard) Security 0 9 18 27 36 45 83 The severe Acute Malnutrition 75% (target) Actual recovery rate was 87% (in Q1) > 75% (standard) Target/standard 0 20 40 60 80 100 Health & The under-five mortality rate was 0.08 0.1 (target) Actual Nutrition per 1,000 children (in Q1) < 1.5 (standard) Target/standard 0.0 0.3 0.6 0.9 1.2 1.5 0 households received emergency 13,616 HHs 0% livelihood support (Q1 data) 0 20 40 60 80 100 Livelihoods & 16 refugees received financial literacy Resilience training (Q1 data) 2,000 Individuals 1% 0 20 40 60 80 100 10,108 cchildren participating in -

END of PROJECT REPORT Use One Template for All CDC Awards

“BAYLOR COLLEGE OF MEDICINE CHILDREN’S FOUNDATION - UGANDA” END OF PROJECT REPORT Use one template for all CDC Awards managed by the organization Send the completed report to Cooperative Agreement’s Activity Manager, the Monitoring Team Lead on [email protected] and Program Grants Office on email [email protected]. For inquiries/comments, send to [email protected] Partner Name: Baylor College of Medicine Children’s Foundation - Uganda Physical Address: Mulago Hospital Complex Block 5, Kampala Program Title: Strengthening National Pediatric HIV/AIDS and Scaling up comprehensive HIV/AIDS Services in The Republic of Uganda under the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) Cooperative Agreement Number: Reporting period: 1st October 2012 – 31st March 2018 Contact Information: (PI, M&E and Finance) Name: Adeodata Kekitiinwa Name: Albert Maganda Name: Title: Executive Director Email:akekitiinwa@bylor- Title: Director Planning and Title: Director Finance uganda.org M&E Email: Tel No:+256 772-462686 Email:amaganda@baylor- Tel No: Signature: uganda.org Signature: Tel No: +256 772-485174 Signature: Date of submission: Acknowledgement and Disclaimer: “This publication was supported by cooperative agreement number “1U2GGH000848-02” from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of CDC.” Page 1 of 82 Table of Contents Table A: Partner intervention area summary ....................................................................................... -

District Multi-Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profile for Kamwenge District

District Multi-hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profile for Kamwenge District District Multi-hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profile a b District Multi-hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profile Acknowledgement On behalf of office of the Prime Minister, I wish to express sincere appreciation to all of the key stakeholders who provided their valuable inputs and support to this hazard, risk and vulnerability mapping exercise that led to the production of comprehensive district hazard, risk and vulnerability profiles for the South Western districts which are Isingiro, Kamwenge, Mbarara, Rubirizi and Sheema. I especially extend my sincere thanks to the Department of Disaster Preparedness and Management in Office of the Prime Minister, under the leadership of Mr. Martin Owor - Commissioner Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Management and Mr. Gerald Menhya - Assistant Commissioner Disaster Preparedness for the oversight and management of the entire exercise. The HRV team was led by Ms. Ahimbisibwe Catherine - Senior Disaster Preparedness Officer, Nyangoma Immaculate - Disaster Preparedness Officer and the team of consultants (GIS/DRR Specialists): Mr. Nsiimire Peter and Mr. Nyarwaya Amos who gathered the information and compiled this document are applauded. Our gratitude goes to the UNDP for providing funds to support the Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Mapping. The team comprised of Mr. Gilbert Anguyo, Disaster Risk Reduction Analyst, Mr. Janini Gerald and Mr. Ongom Alfred for providing valuable technical support in the organization of the exercise. My appreciation also goes to the District Teams: 1. Isingiro District: Mr. Bwengye Emmanuel – Ag. District Natural Resources Officer, Mr. Kamoga Abdu - Environment Officer and Mr. Mukalazi Dickson - District Physical Planner. 2. Kamwenge District: Mr. -

Uganda's Experience in Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak Preparedness

Aceng et al. Globalization and Health (2020) 16:24 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00548-5 RESEARCH Open Access Uganda’s experience in Ebola virus disease outbreak preparedness, 2018–2019 Jane Ruth Aceng1, Alex R. Ario1,2*, Allan N. Muruta1, Issa Makumbi1,3, Miriam Nanyunja4, Innocent Komakech4, Andrew N. Bakainaga4, Ambrose O. Talisuna5, Collins Mwesigye4, Allan M. Mpairwe4, Jayne B. Tusiime4, William Z. Lali4, Edson Katushabe4, Felix Ocom4, Mugagga Kaggwa4, Bodo Bongomin4, Hafisa Kasule4, Joseph N. Mwoga4, Benjamin Sensasi4, Edmund Mwebembezi4, Charles Katureebe4, Olive Sentumbwe4, Rita Nalwadda4, Paul Mbaka4, Bayo S. Fatunmbi6, Lydia Nakiire7, Mohammed Lamorde7, Richard Walwema7, Andrew Kambugu7, Judith Nanyondo7, Solome Okware1,7, Peter B. Ahabwe7, Immaculate Nabukenya1,7, Joshua Kayiwa3, Milton M. Wetaka3, Simon Kyazze3, Benon Kwesiga2, Daniel Kadobera2, Lilian Bulage2,8, Carol Nanziri2, Fred Monje2, Dativa M. Aliddeki2, Vivian Ntono2, Doreen Gonahasa2, Sandra Nabatanzi2, Godfrey Nsereko2, Anne Nakinsige1, Eldard Mabumba1, Bernard Lubwama1, Musa Sekamatte1, Michael Kibuule1, David Muwanguzi1, Jackson Amone1, George D. Upenytho1, Alfred Driwale1, Morries Seru1, Fred Sebisubi1, Harriet Akello1,9, Richard Kabanda1, David K. Mutengeki1, Tabley Bakyaita1, Vivian N. Serwanjja1, Richard Okwi1, Jude Okiria1, Emmanuel Ainebyoona1, Bernard T. Opar1, Derrick Mimbe10, Denis Kyabaggu11, Chrisostom Ayebazibwe12, Juliet Sentumbwe12, Moses Mwanja12, Deo B. Ndumu12, Josephine Bwogi13, Stephen Balinandi13, Luke Nyakarahuka13, Alex Tumusiime13, Jackson Kyondo13, Sophia Mulei13, Julius Lutwama13, Pontiano Kaleebu13, Atek Kagirita14, Susan Nabadda14, Peter Oumo15, Robinah Lukwago16, Julius Kasozi17, Oleh Masylukov18, Henry Bosa Kyobe19, Viorica Berdaga20, Miriam Lwanga20, Joe C. Opio20, David Matseketse20, James Eyul21, Martin O. Oteba9, Hasifa Bukirwa8, Nulu Bulya8, Ben Masiira8, Christine Kihembo8, Chima Ohuabunwo8, Simon N. Antara8, Wilberforce Owembabazi22, Paul B. -

Uganda Country Operational Plan 2018 Strategic Direction Summary

UGANDA Country Operational Plan (COP) 2018 Strategic Direction Summary April 17, 2018 Table of Contents 1.0 Goal Statement .................................................................................................................... 3 2.0 Epidemic, Response, and Program Context ....................................................................... 5 2.1 Summary Statistics, Disease Burden and Country Profile .......................................................... 5 2.2 Investment Profile ...................................................................................................................... 18 2.3 National Sustainability Profile Update ..................................................................................... 22 2.4 Alignment of PEPFAR Investments Geographically to Disease Burden ................................. 26 2.5 Stakeholder Engagement ........................................................................................................... 28 3.0 Geographic and Population Prioritization ....................................................................... 31 4.0 Program Activities for Epidemic Control in Scale-Up Locations and Populations........ 33 4.1 Finding the missing, getting them on treatment, and retaining them .................................... 33 4.2 Prevention, specifically detailing programs for priority programming................................... 50 HIV prevention and risk avoidance for AGYW and OVC .......................................................... 50 Key and Priority