The Feeling of Migration Narratives of Queer Intimacies and Partner Migration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue MAY 31-JUNE / VOL

1 LA WEEKLY | - J , | WWW. LAWEEKLY.COM ® The issue MAY 31-JUNE / VOL. 6, 2019 41 / 28 / NO. MAY LAWEEKLY.COM 2 WEEKLY WEEKLY LA | - J , | - J | .COM LAWEEKLY . WWW Welcome to the New Normal Experience life in the New Normal today. Present this page at any MedMen store to redeem this special offer. 10% off your purchase CA CA License A10-17-0000068-TEMP For one-time use only, redeemable until 06/30/19. Limit 1 per customer. Cannot be combined with any other offers. 3 LA WEEKLY | - J , | WWW. LAWEEKLY.COM SMpride.com empowerment, inclusivity and acceptance. inclusivity empowerment, celebrate the LGBTQ+ community, individuality, individuality, community, the LGBTQ+ celebrate A month-long series of events in Santa Monica to to Monica in Santa of events series A month-long June 1 - 30 4 L May 31 - June 6, 2019 // Vol. 41 // No. 28 // laweekly.com WEEKLY WEEKLY LA Contents | - J , | - J | .COM LAWEEKLY . WWW 13 GO LA...7 this week, including titanic blockbuster A survey and fashion show for out and Godzilla: King of Monsters. influential designer Rudi Gernreich, the avant-garde Ojai Music Festival, the MUSIC...25 FEMMEBIT Festival, and more to do and see Gay Pop artist Troye Sivan curates and in L.A. this week. performs at queer-friendly Go West Fest. BY BRETT CALLWOOD. FEATURE...13 Profiles of local LGBTQ figures from all walks of life leveraging their platforms to improve SoCal. BY MICHAEL COOPER. ADVERTISING EAT & DRINK...19 CLASSIFIED...30 Former boybander Lance Bass brings pride EDUCATION/EMPLOYMENT...31 BY MICHELE STUEVEN. to Rocco’s WeHo. -

Kongen Og Dronningen Av Norske Talkshow

KONGEN OG DRONNINGEN AV NORSKE TALKSHOW - EN SAMMENLIGNENDE ANALYSE AV SKAVLAN OG LINDMO Foto: NRK/Mette Randem Foto: NRK/Evy Andersen AV: LINDA CHRISTINE STRANDE Masteroppgave i medievitenskap Institutt for informasjons- og medievitenskap Universitetet i Bergen Våren 2013 Forord Det er mange som fortjener en takk for å ha hjulpet meg i arbeidet med denne masteroppgaven. Først og fremst vil jeg benytte anledningen til å takke min fantastiske veileder, Jostein Gripsrud. Med dine gode råd, din faglige kompetanse og, ikke minst, ditt upåklagelig gode humør har du ikke bare gjort arbeidet med oppgaven lettere, men også hyggeligere. Jeg er utrolig takknemlig for det. En stor takk vil jeg også rette til Fredrik Skavlan, Anne Lindmo og deres nære medarbeidere Marianne Torp Kierulf, Jan Petter Saltvedt og Stine Traaholt. Jeg setter veldig stor pris på at dere velvillig stilte opp til intervjuer. Jeg opplevde å bli utrolig godt tatt imot av dere, og fikk mange gode svar som har vært til stor nytte for meg i dette forskningsprosjektet. Jeg vil også takke mine kjære medstudenter som har sittet sammen med meg på rom 539. Vi døpte tidlig vårt kontorfellesskap GOE DAGA. Et navn som spesielt de siste, intense månedene har fremstått som mer og mer ironisk. Likevel er jeg sikkert på at vi, etter hvert når skuldrene senker seg, vil se tilbake på tiden som har vært med glede og savn. Vinterning og bråkebøter er begreper jeg alltid vil minnes med et smil om munnen. Sist, men ikke minst, vil jeg også rette en stor takk til familie og venner. Spesielt takk til verdens beste mamma og pappa. -

Integreringsretorikken I Arbeiderpartiet

Integreringsretorikken i Arbeiderpartiet Det nye norske vi Sjur Aaserud Masteroppgave ved institutt for lingvistiske og nordiske studier UNIVERSITETET I OSLO 14/11- 2014 Sammendrag Målet for denne oppgaven er å se på integreringsretorikken til Arbeiderpartiet. Jeg har brukt diskursmodellen til Fairclough for å belyse de ulike sidene av politiske tekster. Denne oppgaven er tredelt. En del er viet de sosiokulturelle arenaene for politiske tekster, den andre er viet den diskursive praksisen innenfor Arbeiderpartiet og det tredje segmentet er viet en teksthermenautisk analyse av Mangfold og muligheter. Forord Det er mange som skal takkes når regnskapet over nesten et og et halv år med masteroppgavejobbing skal gjøres opp. Først og fremst er det mange i selve Arbeiderpartiet jeg må takke: Kristine Kallset, Lise Christoffersen, Jonas Gahr Støre og Håkon Haugli. Min veileder i dette arbeidet har på tross av en ufattelig arbeidsmengde alltid funnet tid til meg og brutt illusjoner, sparket meg i gang og fått fokus på det som skulle bli den røde tråden i arbeidet. Takk Kjell Lars Berge! Ellers vil jeg takke Sindre Bangstad for interessante diskusjoner. Og som alltid min våpendrager Sofus Kjeka som alltid er der for gode diskusjoner. Og sist, men aller viktigst, min kjære Pil som mer eller mindre opprettholdt ”vårt lille vi” i en relativt monoman tilværelse. Innhold SAMMENDRAG ............................................................................................................................. 2 FORORD .......................................................................................................................................... -

Langues, Accents, Prénoms & Noms De Famille

Les Secrets de la Septième Mer LLaanngguueess,, aacccceennttss,, pprréénnoommss && nnoommss ddee ffaammiillllee Il y a dans les Secrets de la Septième Mer une grande quantité de langues et encore plus d’accents. Paru dans divers supplément et sur le site d’AEG (pour les accents avaloniens), je vous les regroupe ici en une aide de jeu complète. D’ailleurs, à mon avis, il convient de les traiter à part des avantages, car ces langues peuvent être apprises après la création du personnage en dépensant des XP contrairement aux autres avantages. TTaabbllee ddeess mmaattiièèrreess Les différentes langues 3 Yilan-baraji 5 Les langues antiques 3 Les langues du Cathay 5 Théan 3 Han hua 5 Acragan 3 Khimal 5 Alto-Oguz 3 Koryo 6 Cymrique 3 Lanna 6 Haut Eisenör 3 Tashil 6 Teodoran 3 Tiakhar 6 Vieux Fidheli 3 Xian Bei 6 Les langues de Théah 4 Les langues de l’Archipel de Minuit 6 Avalonien 4 Erego 6 Castillian 4 Kanu 6 Eisenör 4 My’ar’pa 6 Montaginois 4 Taran 6 Ussuran 4 Urub 6 Vendelar 4 Les langues des autres continents 6 Vodacci 4 Les langages et codes secrets des différentes Les langues orphelines ussuranes 4 organisations de Théah 7 Fidheli 4 Alphabet des Croix Noires 7 Kosar 4 Assertions 7 Les langues de l’Empire du Croissant 5 Lieux 7 Aldiz-baraji 5 Heures 7 Atlar-baraji 5 Ponctuation et modificateurs 7 Jadur-baraji 5 Le code des pierres 7 Kurta-baraji 5 Le langage des paupières 7 Ruzgar-baraji 5 Le langage des “i“ 8 Tikaret-baraji 5 Le code de la Rose 8 Tikat-baraji 5 Le code 8 Tirala-baraji 5 Les Poignées de mains 8 1 Langues, accents, noms -

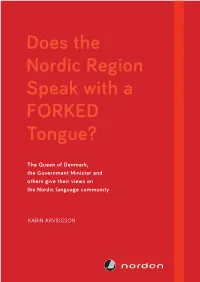

Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue?

Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue? The Queen of Denmark, the Government Minister and others give their views on the Nordic language community KARIN ARVIDSSON Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue? The Queen of Denmark, the Government Minister and others give their views on the Nordic language community NORD: 2012:008 ISBN: 978-92-893-2404-5 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.6027/Nord2012-008 Author: Karin Arvidsson Editor: Jesper Schou-Knudsen Research and editing: Arvidsson Kultur & Kommunikation AB Translation: Leslie Walke (Translation of Bodil Aurstad’s article by Anne-Margaret Bressendorff) Photography: Johannes Jansson (Photo of Fredrik Lindström by Magnus Fröderberg) Design: Mar Mar Co. Print: Scanprint A/S, Viby Edition of 1000 Printed in Denmark Nordic Council Nordic Council of Ministers Ved Stranden 18 Ved Stranden 18 DK-1061 Copenhagen K DK-1061 Copenhagen K Phone (+45) 3396 0200 Phone (+45) 3396 0400 www.norden.org The Nordic Co-operation Nordic co-operation is one of the world’s most extensive forms of regional collaboration, involving Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Åland. Nordic co-operation has firm traditions in politics, the economy, and culture. It plays an important role in European and international collaboration, and aims at creating a strong Nordic community in a strong Europe. Nordic co-operation seeks to safeguard Nordic and regional interests and principles in the global community. Common Nordic values help the region solidify its position as one of the world’s most innovative and competitive. Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue? The Queen of Denmark, the Government Minister and others give their views on the Nordic language community KARIN ARVIDSSON Preface Languages in the Nordic Region 13 Fredrik Lindström Language researcher, comedian and and presenter on Swedish television. -

AUTENTISITETENS GJENNOMSLAGSKRAFT En Studie Av Talkshow Som Arena for Politisk Kommunikasjon

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives AUTENTISITETENS GJENNOMSLAGSKRAFT En studie av talkshow som arena for politisk kommunikasjon Jenny Kanestrøm Trøite Masteroppgave i medievitenskap Universitetet i Oslo - Institutt for medier og kommunikasjon Våren 2012 ii Sammendrag Denne oppgaven undersøker hvordan norske politikere bruker talkshowet som arena for politisk kommunikasjon. Fjernsynet har langt på vei brutt ned grensa mellom informasjon og underholdning, noe som har ført til en framvekst av nye hybridsjangre, nye politikertyper og, ikke minst, en ny politisk retorikk. Talkshowet er et resultat av denne utviklinga, og er derfor et spennende utgangspunkt for å undersøke hvordan norske politikere har tilpassa seg den nye mediesituasjonen. I talkshowet må politikerne stadig skifte mellom de ulike krava som stilles til politikk og underholdning. De må opprettholde den autoriteten og makta de er avhengige av å ha som politikere, samtidig er de nødt til å gi av seg selv og vise sin personlighet for å skape samhold med publikum. En vellykka opptreden i talkshow fordrer derfor at politikeren oppnår en suksessfull sammensmelting av den offentlige og private sfære. Ved hjelp av en innholdsanalyse, som er forankra i retorikkteori og retorisk terminologi, studeres ti talkshowopptredener med sikte på å avsløre hvilke virkemidler politikere bruker for å gi et troverdig inntrykk i slike program. Deretter settes oppgaven inn i et større perspektiv, ved å vise hvordan oppgavens funn kan si noe om hvilken retorikk som er mest hensiktsmessig og overbevisende å benytte for politikere som gjester talkshow. Analysen viser at samtlige politikere i utvalget er storforbrukere av personifisering, som har til hensikt å skape samhold og identifikasjon. -

The Frontier, May 1930

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana The Frontier and The Frontier and Midland Literary Magazines, 1920-1939 University of Montana Publications 5-1930 The Frontier, May 1930 Harold G. Merriam Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/frontier Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Merriam, Harold G., "The Frontier, May 1930" (1930). The Frontier and The Frontier and Midland Literary Magazines, 1920-1939. 32. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/frontier/32 This Journal is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Montana Publications at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Frontier and The Frontier and Midland Literary Magazines, 1920-1939 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FRONTIER \ MAGAZIN€ Of TH€ NORTHWfST MAY Cowboy Can Ride, a drawing by Irving Shope. A Coffin for Enoch, a story by Elise Rushfeldt. Chinook Jargon, by Edward H. Thomas. The Backward States, an essay by Edmund L. Freeman. An Indian Girl's Story of a Trading Expedition to the South west About 1841. Other stories by Ted Olson, Roland English Hartley, William Saroyan, Martin Peterson, Merle Haines. Open Range articles by H. C. B. Colvill, William S. Lewis, Mrs. T , A. Wickes. Poems by Donald Burnie, Elizabeth Needham, Kathryn Shepherd, James Rorty. ■ Frances Huston, W hitley Gray, Eleanor Sickels, Muriel Thurston, Helen Mating, B Margaret Skavlan, James Marshall, Frank Ankenbrand, Jr., Israel Newman. Lillian T . Leonard, Edith M. -

The Great Economic Divide News a Temperature of 7°C (44°F) Norway’S Oil and Was Registered at the Svalbard Gas Sector Brings Airport on Feb

(Periodicals postage paid in Seattle, WA) TIME-DATED MATERIAL — DO NOT DELAY In Your Neighborhood Travel Legacy of Protecting a piece Sverre and Henny Det verste ved å bli eldre of Norwegian- er at ens jevnaldrende er blitt så American history Ulvestad fryktelig gamle. Read more on page 13 – Erik Dibbern Read more on page 9 Norwegian American Weekly Vol. 123 No. 7 February 17, 2012 Established May 17, 1889 • Formerly Western Viking and Nordisk Tidende $1.50 per copy Norway.com News Find more at www.norway.com The great economic divide News A temperature of 7°C (44°F) Norway’s oil and was registered at the Svalbard gas sector brings airport on Feb. 8. This is a new record high for February growth to some on the Arctic archipelago. It is the highest temperature for businesses, while the month ever registered since others struggle registrations began in 1975. The previous record was 6°C with high costs in February 2005, Svalbard- sposten reports. The average AFTEN P OSTEN temperature for February at Longyearbyen is between -15 On Feb. 9, Norsk Industri pre- and 16°C (approximately 5 – sented its annual assessment of 60°F). current condition and outlook for (blog.norway.com/category/ the year. news) “We see the [oil and gas] in- Culture dustry as Norway's golden egg,” says Communications Director Americans, Brits, and Norwe- Finn Langeland of Norsk Industri gians disagree about Steven (Federation of Norwegian Indus- Van Zandt’s new production set in Norway, reports say. The tries), holding up a gold-wrapped New York Times has called Ste- chocolate Easter egg. -

134659711.Pdf (6.102Mb)

Å ta populærmusikk på alvor. - En sjanger- og innholdsanalyse av fjernsynsprogrammet Lydverket som musikkritikk Ola Utaaker Segadal Masteroppgave i medievitenskap Institutt for informasjons- og medievitenskap Universitetet i Bergen Våren 2015 1 Forord Da er masteroppgaven endelig ferdig! Arbeidet med den har vært en tøff, men mest av alt lærerik og inspirerende prosess. Nå når siste setning er skrevet, er det på tide å takke alle som har hjulpet meg underveis. Først og fremst vil jeg takke min veileder Hallvard Moe for gode innspill, inspirasjon, tålmodighet, motivasjon og hyggelige samtaler. Du har gjort en uvurderlig forskjell for dette mastergradsprosjektet. Jeg vil også takke Nasjonalbiblioteket og Karl Erik Andersen for tilrettelegging og produksjon av datamaterialet. Jeg vil takke mamma og pappa for korrekturlesning og kontinuerlig støtte underveis i prosessen. Min søster Katrine har vært tilstede med støtte og positivitet når jeg har trengt det mest – takk for det! Jeg vil takke Øyvind, Balder, Daniel, Liv, Kari og Andreas på lesesal 644 for gode faglige diskusjoner, løsning av verdensproblemer og mange hyggelige avbrekk. Dere har bidratt til å gjøre hverdagen trivelig gjennom hele perioden. Jeg vil takke de ansatte ved SV-biblioteket for å møte meg med et smil og alltid stille AV- rommet under trappen til min disposisjon. Jeg vil takke alle vennene mine som har holdt ut maset om “masteren” i tide og utide. Til slutt vil jeg takke Sunniva for all kjærlighet, støtte, tålmodighet og hjelp gjennom denne tiden. Uten deg hadde denne prosessen vært mye vanskeligere. Bergen, 18 mai. 2015. Ola Utaaker Segadal 2 INNHOLDSFORTEGNELSE FORORD ................................................................................................................................................ 2 1. INNLEDNING ................................................................................................................................... -

—Jeg Var Bevisst På at Man Ikke Skulle Greie Å Knekke Meg Som

Nr. 9 — 2. mars 2012 — www.ukeavisenledelse.no — 25. årgang — Løssalg kr 35 A-PostAbonnement Møkklei Sponheim RuN Automatiserer B bergens byrådsleder, forretningsdriften RGEN monica mæland, mener Jø CRM – alt på ett sted Fylkesmannen er blitt et ANS 815 48 333 – www.vegasmb.no Foto: H demokratisk problem. side 30 Foto: HALLGEIR VÅGENES/ScANpIx Jonas Gahr Støre såret ham mest: Bedriftseier og —Jeg var bevisst tidligere president i NHO Paul-Chr. Rieber på at man ikke forteller hvordan han opplevde prosessen skulle greie som førte til at han måtte trekke seg å knekke meg fra næringslivets høyeste tillitsverv. som person side 18 Hvorfor Hvorfor Hvorfor HÆRlig ledelse: k Delmål Lederverktøy: ELLEVI H Delmål N Hovedmål Hærens øverste ko Å Helsefarlig H Delmål Delmål Lær å AG Når operative sjef, Per Paul Fugelli Chaffey Foto: D Hvordan jobbkultur? Hvem bruke Odin Johannessen, skriver Hvordan Hvem —Ja, mener medisinprofessor Per Fugelli. Tidslinje om oppdrags basert ledelse Hvordan Hvem målkart —Urettferdig sagt, mener Paul Chaffey i Dato side 26 side 22 Abelia. side 12–14 Når ordet er ditt! I møter, presentasjoner, forhandlinger og salg. Et strålende, morsomt og matnyttig dagskurs med to av Norges beste forelesere. Meld deg på kursdag med skuespiller Per Christian Ellefsen og coach/forfatter Ragnhild Nilsen. Tid: 26. april 2012 kl 09:00 – 15:30 Sted: Gamle sjømannskolen Ekeberg Oslo Pris: 1950,- www.coachteam.no – [email protected] – telefon 40 00 45 00 2 Ved redaktør Magne Lerø LEDERPLASS [email protected] Ineffektivt sykehusbyråkrati Foto: SP Problemet innen sykehusene er ikke at det er for få politikere på ballen. -

05B13 Programmkino St

CI NEMA B PA R ADIS O 05B13 Programmkino St. Pölten 1. Programmkino in NÖ, 02742-21 400, www.cinema-paradiso.at B EDITORIAL 100 Jahre gibt es Kino in St. Pölten! Gemeinsam mit der Kultur verwaltung und dem Stadt - museum blickt Cinema Paradiso bei den Filmtagen St. Pölten zurück auf die goldene Zeit der ersten Kinos. Aufwendig digitalisiertes Archivmaterial wird erstmals der Öffentlichkeit gezeigt. Der große Gatsby ist heuer der Eröffnungsfilm der Filmfestspiele von Cannes. Die mit großer Spannung erwartete Neu-Verfilmung des Literaturklassikers fängt den Zauber der vibrierenden 1920er-Jahre in atemberaubenden 3D-Bildern ein. Aus der Starbesetzung ragen die beiden HauptdarstellerInnen heraus: Leonardo DiCaprio und Carey Mulligan sind ein Traumpaar. Große Ö-Premiere feiern wir mit Hai-Alarm am Müggelsee . Sven Regener und Leander Hauß - mann sind zu Gast im Kino. Stoker – Die Unschuld endet (Nicole Kidman ) erzählt spannend wie ein Hitchcock-Krimi und visuell eindrucksvoll eine geheimnisvolle, sinnliche Familienge - schichte. Die elegante, geistreiche Komödie Eine Dame in Paris bringt die Grande Dame des französischen Kinos Jeanne Moreau als kokette, herrische, alte Lady auf die Leinwand. ¡No! bannt packend eine wahre Geschichte auf die Leinwand. Ein Marketingberater leitet die Werbekampagne der Opposition gegen die Diktatur Pinochets. Im unbeschwerten, antikapita - listischen Gute-Laune-Film Diamantenfieber ist Josef Hader endlich wieder im Kino zu sehen. Mutter & Sohn (Berlinale 2013: Goldener Bär) wirft kraftvoll und spannend wie ein Krimi die moralische Frage auf: Wo sind die Grenzen der Mutter liebe? Die Wilde Zeit fängt das Flair der wilden 1960er-Jahre so perfekt ein, dass sich unweigerlich die große Sehnsucht beim Kino - besucher einstellt: wäre ich nur dabei gewesen! Ehrlich, sensibel und humorvoll porträtiert Ein freudiges Ereignis das Elternwerden und Elternsein in der modernen Welt. -

Golden Start to Oslo 2011

(Periodicals postage paid in Seattle, WA) TIME-DATED MATERIAL — DO NOT DELAY Research & Education Taste of Norway More pressure on A saucy new twist Norwegian Nobel Jeg tør si, vi elsket våre ski. Vi klappet with Ski Queen og kjælte dem hver gang vi spente Committee dem på. cheese Read more on page 3 – Roald Amundsen Read more on page 8 Norwegian American Weekly Vol. 122 No. 9 March 4, 2011 Established May 17, 1889 • Formerly Western Viking and Nordisk Tidene $1.50 per copy Norway.com News Find more at www.norway.com Golden start to Oslo 2011 News of Norway After years of Searchers have failed to find preparation, the a Norwegian yacht missing in frigid Antarctic waters for sev- FIS World Ski eral days with three crew mem- Championships are bers aboard, officials said Feb. 28. Two other crew members of underway in Oslo “The Berserk” were rescued. (blog.norway.com/category/ news) STAFF COMPILATION Norwegian American Weekly Norway in the U.S. As part of its monthlong maxi- mumINDIA festival, the Kenne- Neither snow nor sleet nor dy Center in Washington, D.C., a sudden (and fortunately short) presents an Indian-inflected ver- breakdown of Oslo’s public transit sion of Henrik Ibsen’s final play, metro line would ruin the start of “When We Dead Awaken.” In the FIS Nordic World Ski Cham- this adaptation, scenes from the pionships (Ski-VM) in the Norwe- original play have been picked gian capital. up and interpolated, without Under a clear winter sky on distorting the original idea and Feb.