By David Webster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Heroes in Indonesian History Text Book

Paramita:Paramita: Historical Historical Studies Studies Journal, Journal, 29(2) 29(2) 2019: 2019 119 -129 ISSN: 0854-0039, E-ISSN: 2407-5825 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15294/paramita.v29i2.16217 NATIONAL HEROES IN INDONESIAN HISTORY TEXT BOOK Suwito Eko Pramono, Tsabit Azinar Ahmad, Putri Agus Wijayati Department of History, Faculty of Social Sciences, Universitas Negeri Semarang ABSTRACT ABSTRAK History education has an essential role in Pendidikan sejarah memiliki peran penting building the character of society. One of the dalam membangun karakter masyarakat. Sa- advantages of learning history in terms of val- lah satu keuntungan dari belajar sejarah dalam ue inculcation is the existence of a hero who is hal penanaman nilai adalah keberadaan pahla- made a role model. Historical figures become wan yang dijadikan panutan. Tokoh sejarah best practices in the internalization of values. menjadi praktik terbaik dalam internalisasi However, the study of heroism and efforts to nilai. Namun, studi tentang kepahlawanan instill it in history learning has not been done dan upaya menanamkannya dalam pembelaja- much. Therefore, researchers are interested in ran sejarah belum banyak dilakukan. Oleh reviewing the values of bravery and internali- karena itu, peneliti tertarik untuk meninjau zation in education. Through textbook studies nilai-nilai keberanian dan internalisasi dalam and curriculum analysis, researchers can col- pendidikan. Melalui studi buku teks dan ana- lect data about national heroes in the context lisis kurikulum, peneliti dapat mengumpulkan of learning. The results showed that not all data tentang pahlawan nasional dalam national heroes were included in textbooks. konteks pembelajaran. Hasil penelitian Besides, not all the heroes mentioned in the menunjukkan bahwa tidak semua pahlawan book are specifically reviewed. -

Praktik Pengalaman Lapangan Fakultas Keguruan Dan Ilmu Pendidikan SD Negeri Locondong

Praktik Pengalaman Lapangan Fakultas Keguruan dan Ilmu Pendidikan SD Negeri Locondong PENGGUNAAN METODE COOPERATIVE LEARNING DALAM PEMBELAJARAN TEMA 5 PAHLAWANKU SUBTEMA 3 SIKAP KEPAHLAWANAN Nuf Anggraeni*1, Galuh Rahayuni2 Universitas Nahdlatul Ulama Al-Ghazali (UNUGHA) Cilacap Fakultas Keguruan dan Ilmu Pendidikan Program Studi Pendidikan Guru Sekolah Dasar A. Pendahuluan Pembelajaran yang dilakukan pada tema 5 Pahlawanku Subtema 3 Sikap Kepahlawanan Pembelajaran 1 menggunakan model pembelajaran Cooperative Learning. Metode pembelajaran yang digunakan dalam pembelajaran yang digunakan dalam pembelajaran yaitu, Ceramah, Diskusi, Tanya Jawab dan Permainan. Pembelajaran yang dilakukan di kelas IV B dilakukan selama 3 jam pembelajaran, dimana 1 jam pelajaran 35 Menit. Satu pertemuan dilakukan selama 105 Menit untuk kegiatan awal, kegiatan inti dan kegiatan penutup. Jumlah siswa di kelas IV B adalah 20 siswa. Materi yang digunakan menggunakan sumber dan buku siswa dan buku guru Tema 5 Pahlawanku Subtema 3 Sikap Kepahlawanan Pembelajaran 1. Mata pelajaran yang termuat didalamnya yaitu IPA, IPS dan Bahasa Indonesia. Mata pelajaran IPA mengenai materi cermin cembung dan cermin cekung, dan pata pelajaran IPS mengenai materi nama Pahlawan Nasional Indonesia. Mata pelajaran Bahasa Indonesia mengenai materi menulis informasi dari teks non fiksi. Penanganan terhadap siswa yang mengalami kesulitan pada saat pembelajaran adalah mendekati dan memberikan bimbingan kepada siswa secara langsung. Kegaduhan yang ditimbulkan oleh siswa ditangani dengan menggunakan beberapa tepuk semangat jilid dua dan tepuk konsentrasi agar konsentrasi kembali pada pembelajaran. Selain itu pada jumlah siswa yang banyak maka dalam pembelajaran harus menggunakan suara yang keras. B. Pembahasan 1. Materi Pembelajaran yang dilakukan di kelas IV B memuat 3 mata pelajaran yaitu IPA, IPS dan Bahasa Indonesia. -

Pengumuman-Tahap-1-Ppdb

YAYASAN ARDHYA GARINI PENGURUS PUSAT YAYASAN ARDHYA GARINI SMA PRADITA DIRGANTARA PENGUMUMAN Nomor : Peng / 2 / III / 2021/SMAPD HASIL SELEKSI TAHAP 1 PENERIMAAN PESERTA DIDIK BARU SMA PRADITA DIRGANTARA TAHUN PELAJARAN 2021/2022 1. Berdasarkan hasil sidang penentuan akhir yang dilaksanakan pada hari Jumat tanggal 19 Maret 2021 tentang penetapan hasil seleksi tahap 1 Penerimaan Peserta Didik Baru (PPDB) SMA Pradita Dirgantara Tahun Ajaran 2021/2022, dengan ini diberitahukan ketentuan sebagai berikut : a. Hasil seleksi tahap 1 Penerimaan Peserta Didik Baru SMA Pradita Dirgantara Tahun Pelajaran 2021/2022 yang dinyatakan LULUS dan memenuhi syarat, sebagaimana tersebut dalam lampiran pengumuman ini. b. Bagi yang dinyatakan lulus agar segera melakukan konfirmasi dan melaporkan ke Lanud terdekat. c. Batasan konfirmasi adalah hari Kamis tanggal 25 Maret 2021 pukul 12.00 WIB, bila tidak memberikan konfirmasi dinyatakan mengundurkan diri. d. Pelaksanaan seleksi pusat akan diumumkan lebih lanjut melalui pengumuman tersendiri. 2. Demikian disampaikan, agar para siswa segera melakukan konfirmasi pengumuman ini, atas perhatiannya diucapkan terimakasih. A.n. Ketua Umum Ketua PPDB SMA Pradita Dirgantara Ny. Sondang Khairil Lubis Lampiran Pengumuman Daftar Nama Peserta Lolos Seleksi Tahap 1 NO KODE DAFTAR NAMA JK ASAL PANDA 1 2 3 4 5 1 PRAK-83JQEKIC Az Zahra Leilany Widjanarka P Lanud Abdul Rachman Saleh (ABD), Malang 2 PRAK-8TM1YQGC Glenn Emmanuel Abraham L Lanud Abdul Rachman Saleh (ABD), Malang 3 PRAK-202101-0879 Kayana Nur Ramadhania P Lanud Abdul -

Teuku Mohammad Hasan (Sumatra), Soetardjo Kartohadikoesoemo (Jawa Barat), R

GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA KEMENTERIAN PENDIDIKAN DAN KEBUDAYAAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA PENGARAH Hilmar Farid (Direktur Jenderal Kebudayaan) Triana Wulandari (Direktur Sejarah) NARASUMBER Suharja, Mohammad Iskandar, Mirwan Andan EDITOR Mukhlis PaEni, Kasijanto Sastrodinomo PEMBACA UTAMA Anhar Gonggong, Susanto Zuhdi, Triana Wulandari PENULIS Andi Lili Evita, Helen, Hendi Johari, I Gusti Agung Ayu Ratih Linda Sunarti, Martin Sitompul, Raisa Kamila, Taufik Ahmad SEKRETARIAT DAN PRODUKSI Tirmizi, Isak Purba, Bariyo, Haryanto Maemunah, Dwi Artiningsih Budi Harjo Sayoga, Esti Warastika, Martina Safitry, Dirga Fawakih TATA LETAK DAN GRAFIS Rawan Kurniawan, M Abduh Husain PENERBIT: Direktorat Sejarah Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Jalan Jenderal Sudirman, Senayan Jakarta 10270 Tlp/Fax: 021-572504 2017 ISBN: 978-602-1289-72-3 SAMBUTAN Direktur Sejarah Dalam sejarah perjalanan bangsa, Indonesia telah melahirkan banyak tokoh yang kiprah dan pemikirannya tetap hidup, menginspirasi dan relevan hingga kini. Mereka adalah para tokoh yang dengan gigih berjuang menegakkan kedaulatan bangsa. Kisah perjuangan mereka penting untuk dicatat dan diabadikan sebagai bahan inspirasi generasi bangsa kini, dan akan datang, agar generasi bangsa yang tumbuh kelak tidak hanya cerdas, tetapi juga berkarakter. Oleh karena itu, dalam upaya mengabadikan nilai-nilai inspiratif para tokoh pahlawan tersebut Direktorat Sejarah, Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan, Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan menyelenggarakan kegiatan penulisan sejarah pahlawan nasional. Kisah pahlawan nasional secara umum telah banyak ditulis. Namun penulisan kisah pahlawan nasional kali ini akan menekankan peranan tokoh gubernur pertama Republik Indonesia yang menjabat pasca proklamasi kemerdekaan Indonesia. Para tokoh tersebut adalah Teuku Mohammad Hasan (Sumatra), Soetardjo Kartohadikoesoemo (Jawa Barat), R. Pandji Soeroso (Jawa Tengah), R. -

State Societyand Governancein Melanesia

THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies State, Society and Governance in Melanesia StateSociety and in Governance Melanesia DISCUSSION PAPER Discussion Paper 2005/6 DECENTRALISATION AND ELITE POLITICS IN PAPUA ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION JAAP TIMMER This paper focuses on conflicts in the Province For a number of reasons ranging from Dutch of Papua (former Irian Jaya) that were stimulated nationalism, geopolitical considerations, and self- by the recent devolution of power of administrative righteous moral convictions, the Netherlands functions in Indonesia. While the national Government refused to include West New decentralisation policy aims at accommodating Guinea in the negotiations for the independence anti-Jakarta sentiments in the regions and of Indonesia in the late 1940s (Lijphart 1966; intends to stimulate development, it augments Huydecoper van Nigtevecht 1990; Penders 2002: contentions within the Papuan elite that go hand Chapter 2; and Vlasblom 2004: Chapter 3). At the in hand with ethnic and regional tensions and same time, the government in Netherlands New increasing demands for more sovereignty among Guinea initiated economic and infrastructure communities. This paper investigates the histories development as well as political emancipation of of regional identities and Papuan elite politics the Papuans under paternalistic guardianship. In in order to map the current political landscape the course of the 1950s, when tensions between in Papua. A brief discussion of the behaviour of the Netherlands and Indonesia grew over the certain Papuan political players shows that many status of West New Guinea, the Dutch began to of them are enthused by an environment that guide a limited group of educated Papuans towards is no longer defined singly by centralised state independence culminating in the establishment control but increasingly by regional opportunities of the New Guinea Council (Nieuw-Guinea Raad) to control state resources and to make profitable in 1961. -

List of English and Native Language Names

LIST OF ENGLISH AND NATIVE LANGUAGE NAMES ALBANIA ALGERIA (continued) Name in English Native language name Name in English Native language name University of Arts Universiteti i Arteve Abdelhamid Mehri University Université Abdelhamid Mehri University of New York at Universiteti i New York-ut në of Constantine 2 Constantine 2 Tirana Tiranë Abdellah Arbaoui National Ecole nationale supérieure Aldent University Universiteti Aldent School of Hydraulic d’Hydraulique Abdellah Arbaoui Aleksandër Moisiu University Universiteti Aleksandër Moisiu i Engineering of Durres Durrësit Abderahmane Mira University Université Abderrahmane Mira de Aleksandër Xhuvani University Universiteti i Elbasanit of Béjaïa Béjaïa of Elbasan Aleksandër Xhuvani Abou Elkacem Sa^adallah Université Abou Elkacem ^ ’ Agricultural University of Universiteti Bujqësor i Tiranës University of Algiers 2 Saadallah d Alger 2 Tirana Advanced School of Commerce Ecole supérieure de Commerce Epoka University Universiteti Epoka Ahmed Ben Bella University of Université Ahmed Ben Bella ’ European University in Tirana Universiteti Europian i Tiranës Oran 1 d Oran 1 “Luigj Gurakuqi” University of Universiteti i Shkodrës ‘Luigj Ahmed Ben Yahia El Centre Universitaire Ahmed Ben Shkodra Gurakuqi’ Wancharissi University Centre Yahia El Wancharissi de of Tissemsilt Tissemsilt Tirana University of Sport Universiteti i Sporteve të Tiranës Ahmed Draya University of Université Ahmed Draïa d’Adrar University of Tirana Universiteti i Tiranës Adrar University of Vlora ‘Ismail Universiteti i Vlorës ‘Ismail -

Klasifikasi Dan Pemeringkatan Perguruan Tinggi Indonesia

KLASIFIKASI DAN PEMERINGKATAN PERGURUAN TINGGI INDONESIA Kualitas Kode Kualitas Kualitas Keg No. Nama PT Kualitas SDM Penelitian & Skor Total Peringkat Cluster PT Manajemen Mahasiswa Publikasi 1 2001 Institut Teknologi Bandung 3.93 3.9 1.9 4.0 3.743 1 1 2 1001 Universitas Gadjah Mada 3.99 4.0 4.0 3.0 3.690 2 1 3 2003 Institut Pertanian Bogor 4.00 3.9 1.8 3.1 3.490 3 1 4 1002 Universitas Indonesia 3.86 3.9 1.6 3.0 3.412 4 1 5 2002 Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember 3.76 4.0 2.3 2.5 3.289 5 1 6 1019 Universitas Brawijaya 3.68 3.8 2.0 2.5 3.217 6 1 7 1007 Universitas Padjadjaran 3.58 3.8 0.3 2.7 3.075 7 1 8 1004 Universitas Airlangga 3.74 3.7 1.4 2.3 3.064 8 1 9 1027 Universitas Sebelas Maret 3.63 3.9 0.2 2.6 3.035 9 1 10 1008 Universitas Diponegoro 3.59 3.8 0.4 2.4 2.983 10 1 11 1005 Universitas Hasanuddin 3.59 3.8 0.0 2.6 2.978 11 1 12 1006 Universitas Andalas 3.61 3.6 0.2 1.9 2.753 12 2 13 1033 Universitas Negeri Malang 3.89 3.8 0.3 1.4 2.742 13 2 14 1038 Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta 3.74 3.5 0.6 1.7 2.726 14 2 15 71002 Universitas Kristen Petra 3.22 3.9 0.0 1.7 2.655 15 2 16 1023 Universitas Jenderal Soedirman 3.34 3.4 0.5 1.6 2.543 16 2 17 1041 Universitas Negeri Semarang 3.59 3.2 0.4 1.5 2.541 17 2 18 5018 Politeknik Elektronik Negeri Surabaya 3.49 4.0 0.1 0.9 2.516 18 2 19 1034 Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia 3.68 3.2 0.3 1.4 2.498 19 2 20 1017 Universitas Riau 3.59 3.0 0.1 1.6 2.477 20 2 21 1039 Universitas Negeri Surabaya 3.64 3.2 0.1 1.3 2.453 21 2 22 1026 Universitas Lampung 3.60 3.4 0.0 1.1 2.440 22 2 23 1009 Universitas Sriwijaya -

The Resistance of People in Papua (1945-1962)

HISTORIA: International Journal of History Education, Vol. X, No. 2 (December 2009) THE RESISTANCE OF PEOPLE IN PAPUA (1945-1962) Onie M. Lumintang 1 ABSTRACT This article discusses a sequence of events showing the resistance of the people of Papua since 1945 until 1965. This resistance was conducted by the movement fi gures of Papua who were aggressively struggling for the independence of Indonesia or claiming the independence for the land of Papua. This Movement was conducted in various areas with different resistance targets and forms. Key words: Resistance of People, National Movement, Papua. Introduction Even though the West New Guinea (Papua now) had offi cially been included under the power of the Dutch Indies (Netherlands Indië) starting from the 24th of August 1828; in reality it was on the 8th of October 1898 that the government of the Dutch colonial (later referred to as PKB) seriously upheld its power of that area by building its fi rst governance post in Fak-Fak and Manokwari. Later, it was continued by the building of the governance post in Merauke on the 14th of February 1902, after the Den Haag Convention on May 16, 1895. There was an agreement in the Convention between the Netherland Kingdom and the United Kingdom concerning the division of their colonized area in New Guinea or Papua, namely starting from the south coast of the island in the centre of the estuary of Bens Bach, 1400 1’ 47” BT, continuing to the north by following its stream as the natural boundary and reaching the north coast of that island at 1400 BT, ( K.W mark in line W.C. -

D. Pemikiran, Karya Dan Perjuangan Rahmah El Yunusiah 1

TOKOH INSPIRATIF BANGSA TOKOH INSPIRATIF BANGSA KEMENTERIAN PENDIDIKAN DAN KEBUDAYAAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA 1 2 TOKOH INSPIRATIF BANGSA TOKOH INSPIRATIF BANGSA RAHMAH EL-YUNUSIYAH RADEN AYU LASMININGRAT I GUSTI AYU RAPEG OPU DAENG RISAJU INA BALA WATTIMENA STEVANUS RUMBEWAS 3 TOKOH INSPIRATIF BANGSA PENGARAH Hilmar Farid – Direktur Jenderal Kebudayaan Triana Wulandari – Direktur Sejarah NARASUMBER Amurwani Dwi Lestariningsih Suharja EDITOR A A Bagus Wirawan, Mohammad Iskandar Siti Fatimah PEMBACA UTAMA Anhar Gonggong, Susanto Zuhdi Triana Wulandari, Umasih PENULIS Ajisman, Bernard Meterai Efrianto, Linda Sunarti, Mukhlis PaEni Nuryahman, Rosmaida Sinaga, Undri, Zusneli Zubir TATA LETAK DAN GRAFIS Mawanto Rizki Perdana SEKRETARIAT DAN PRODUKSI Tirmizi, Isak Purba, Bariyo, Haryanto Maemunah, Dwi Artiningsih, Budi Harjo Sayoga Esti Warastika, Martina Safitry, Dirga Fawakih PENERBIT: Direktorat Sejarah Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Jalan Jenderal Sudirman, Senayan Jakarta 10270 Tlp/Fax: 021-5725044 @2017 ISBN: 978-602-1289-74-7 4 TOKOH INSPIRATIF BANGSA DAFTAR ISI SAMBUTAN 6 Direktur Sejarah Direktur Jenderal Kebudayaan PENDAHULUAN 10 RAHMAH EL-YUNUSIYAH 18 R. A. LASMINIGRAT 148 I GUSTI AYU RAPEG 194 OPU DAENG RISAJU 300 INA BALA WATTIMENA 412 STEVANUS RUMBEWAS 506 DAFTAR PUSTAKA 584 5 SAMBUTAN DIREKTUR SEJARAH Puji syukur Alhamdulillah kita panjatkan kepada Tuhan Yang Maha Esa, karena atas rahmat dan hidayah-Nya penerbitan buku ini dapat terwujud. Kegiatan penulisan Buku Tokoh Inspiratif Bangsa, adalah salah satu upaya untuk mengungkapkan peranan dan pengaruh tokoh pejuang bangsa yang bergerak dalam bidang pendidikan, jurnalisme, ekonomi, sosial, politik, budaya dan agama dalam memperjuangkan dan membangun bangsa Indonesia. Tokoh Inspiratif yang dibahas dalam buku ini adalah mereka berjuang untuk kaumnya karena struktur sosial yang dianggap tidak mendukung masyarakat untuk maju dan berkembang. -

Kepres No. 66 Tahun 1955.Pdf

PRESIDEN REPUBLIK INDONESIA KEPUTUSAN PRESIDEN REPUBLIK INDONESIA No. 66 TAHUN 1955 KAMI, PRESIDEN REPUBLIK INDONESIA Membatja : bahwa berhubung di Bandung akan diadakan Koperensi Asia Afrika maka dipandang perlu untuk mengirimkan suatu Delegasi buat menghadiri Konperensi itu; Mengingat : surat putusan Perdana menteri No. 36/P.M./1955 dan putusan Menteri Luar Negeri No. S.P./1/P.D./55 tertanggal 8 Djanuari 1955; Setelah mendengar : Perdana Menteri, Menteri Luar Negeri, Menteri Keuangan, Kpala Kantor urusan Pegawai, Pimpinan Lembaga Alat-alat Pembajaran Luar Negeri, Kepada Djawatan Perdjalanan; Mendengar : Dewan Menteri dalam rapatnja jang ke-100 pada tanggal 15 Maret 1955 MEMUTUSKAN : Menetapkan : Pertama : Mengirimkan suatu Delegasi untuk menghadiri Konperensi Asia- Afrika jang akan dimulai di Bandung pada tanggal 18 April 1955 dan akan berlangsung kurang lebih satu minggu; Kedua : Menentukan susunan Delegasi sebagai berikut : A. Anggota-anggota : 1. Mr. Ali Sastroamidjojo, Perdana Menteri, Ketua Delegasi 2. Mr. Sunario, Menteri Luar Negeri, Wakil Ketua Delegasi 3. Prof. Ir. Roosseno, Menteri Perekonomian 4. Mr. Muhammad Yamin, Menteri Pendidikan, Pengadjaran dan Kebudajaan 5. K.H. Masjkur, Menteri Agama 6. Dr. F.L. Tobing, Menteri Penerangan 7. Mr. Achmad Subardjo, Penasehat Kementerian Luar Negeri 8. Mr. Abu Hanifah, Penasehat Kementerian Luar Negeri 9. Mr. Sujono Hadinoto, Penasehat Kementerian Luar Negeri 10. Ruslan Abdulgani, Sekretaris Djenderal Kementerian Luar Negeri 11. Sukardjo Wirjopranoto, Kepala Direktorat I, Kementerian Luar Negeri 12. Mr. Nazir Datuk Pamontjak, Kepala Direktorat II Kementerian Luar Negeri 13. Mr. Utojo Ramelan, Kepala Direktorat IV Kementerian Luar Negeri PRESIDEN REPUBLIK INDONESIA - 2 - 14. Ir. Djuanda, Kepala Biro Perantjang Negara 15. L.N. Palar, Duta Besar Republik Indonesia di New Delhi 16. -

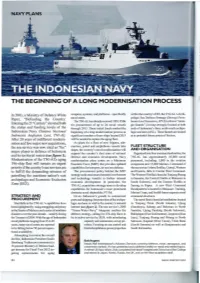

The Indonesian Navy Instability and Being Low Priority with the Merged Speed Increase from 3.5 Knots, and the Maintains a Frigate Inventory of Six Upgraded Services

NAVY PLANS THE BEGINNING OF A LONG MODERNISATION PROCESS In 2003, a Ministry of Defence White weapons, systems, and platforms - specifically within the count ry 's EEZ, theTNI-AL's Archi Paper, "Defending the Country: nava l assets. pelagic Sea Defence Strategy (Strategi Perta The TN I-AL has already received US$ I.958n /umall Lalli NI/sal/tara, SPLN) refers to "strate Entering the 21 " CentlllY" elevated both for procurement of up to 24 naval vessels gic funnels" (CO I'Ollg stmtegis) located at both the status and funding levels of the through 201 3. These ini tial funds marked the ends of Indonesia's three north-south archipe Indonesian Navy (Ten/ara Nasional beginn ing of a long modernisation process as lagic sea lanes (ASL). These funnels are looked Indonesia Angka/an Lout, TNI-Al). significant numbers of new ships beyond 2013 at as potenti al fu ture points of fr iction. After 20 years of indifferent moderni will be needed to replace the agi ng fl eet. sation and few maj or new acquisitions, As plans fo r a fl eet of new fri gates, sub the sea service was now cited as "the" marines, patrol and amphibious vessels take FLEET STRUCTURE AND ORGANISATION major player in defence of Indonesia shape, the country's naval modernisati on will support the country's dual aim s of national Organi sed into fourcolllmand authorities, the and its territorial waters (seejigll,.e 1)_ defence and economic development. Navy T NI-AL has approximately 45,000 naval Modernisati on of the TNI-AI:s aging modernisation pl ans centre on a Minimum personn el, including 1,000 in the aviati on 196-ship fl eet will remain an urgent Essential Force (MEF) that provides updated component and 15,000 Marines. -

Rekonstruksi Sejarah Umat Islam Di Tanah Papua

Rekonstruksi Sejarah Umat Islam Di Tanah Papua DISERTASI Diajukan untuk melengkapi persyaratan mencapai Gelar Doktor dalam Ilmu Agama Islam oleh : Toni Victor M. Wanggai 02.3.00.1.04.01.0070 Promotor : Prof. Dr. Azyumardi Azra, M.A. Dr. Uka Tjandrasasmita SEKOLAH PASCASARJANA UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI (UIN) SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA 2008 M/1429 H ii PERSETUJUAN Disertasi dengan judul : “Rekonstruksi Sejarah Umat Islam di Tanah Papua” yang ditulis oleh Toni Victor M. Wanggai, NIM. 02.3.00.1.04.01.0070, telah diperbaiki sesuai dengan saran dan komentar dari Tim Penguji pada Ujian Pendahuluan Disertasi tanggal 31 Agustus 2008, dapat disetujui untuk dibawa ke Sidang Promosi Doktor (Ujian Terbuka). Jakarta, November 2008 Ketua Sidang / merangkap Promotor, Prof. Dr. Azyumardi Azra, M.A. iii PERSETUJUAN Disertasi dengan judul : “Rekonstruksi Sejarah Umat Islam di Tanah Papua” yang ditulis oleh Toni Victor M. Wanggai, NIM. 02.3.00.1.04.01.0070, telah diperbaiki sesuai dengan saran dan komentar dari Tim Penguji pada Ujian Pendahuluan Disertasi tanggal 31 Agustus 2008, dapat disetujui untuk dibawa ke Sidang Promosi Doktor (Ujian Terbuka). Jakarta, November 2008 Promotor/ merangkap Penguji, Dr.Uka Tjandrasasmita iv PERSETUJUAN Disertasi dengan judul : “Rekonstruksi Sejarah Umat Islam di Tanah Papua” yang ditulis oleh Toni Victor M. Wanggai, NIM. 02.3.00.1.04.01.0070, telah diperbaiki sesuai dengan saran dan komentar dari Tim Penguji pada Ujian Pendahuluan Disertasi tanggal 31 Agustus 2008, dapat disetujui untuk dibawa ke Sidang Promosi Doktor (Ujian Terbuka). Jakarta, November 2008 Penguji, Prof. Dr. Badri Yatim, M.A. v PERSETUJUAN Disertasi dengan judul : “Rekonstruksi Sejarah Umat Islam di Tanah Papua” yang ditulis oleh Toni Victor M.