Erring Decentralization and Elite Politics in Papua

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Butcher, W. Scott

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project WILLIAM SCOTT BUTCHER Interviewed by: David Reuther Initial interview date: December 23, 2010 Copyright 2015 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Dayton, Ohio, December 12, 1942 Stamp collecting and reading Inspiring high school teacher Cincinnati World Affairs Council BA in Government-Foreign Affairs Oxford, Ohio, Miami University 1960–1964 Participated in student government Modest awareness of Vietnam Beginning of civil rights awareness MA in International Affairs John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies 1964–1966 Entered the Foreign Service May 1965 Took the written exam Cincinnati, September 1963 Took the oral examination Columbus, November 1963 Took leave of absence to finish Johns Hopkins program Entered 73rd A-100 Class June 1966 Rangoon, Burma, Country—Rotational Officer 1967-1969 Burmese language training Traveling to Burma, being introduced to Asian sights and sounds Duties as General Services Officer Duties as Consular Officer Burmese anti-Indian immigration policies Anti-Chinese riots Ambassador Henry Byroade Comment on condition of embassy building Staff recreation Benefits of a small embassy 1 Major Japanese presence Comparing ambassadors Byroade and Hummel Dhaka, Pakistan—Political Officer 1969-1971 Traveling to Consulate General Dhaka Political duties and mission staff Comment on condition of embassy building USG focus was humanitarian and economic development Official and unofficial travels and colleagues November -

PAYING for PROTECTION the Freeport Mine and the Indonesian Security Forces

global witness PAYING FOR PROTECTION The Freeport mine and the Indonesian security forces A report by Global Witness July 2005 2 Paying for Protection Contents Paying for Protection: an overview . 3 Soeharto’s Indonesia . 7 Freeport in Papua . 9 “False and irrelevant” versus “almost hysterical denial”: Freeport and the investors . 12 Box: The ambush of August 2002 . 16 The “Freeport Army” . 18 Box: What Freeport McMoRan said ... and didn’t say . 19 General Simbolon’s dinner money . 21 Box: Mahidin Simbolon in East Timor and Papua . 23 Paying for what exactly? . 27 From individuals to institutions? . 28 Building better communities . 28 Paying for police deployments? . 29 Conclusion . 30 Box: Transparency of corporate payments in Indonesia . 30 Box: What Rio Tinto said ... and didn’t say . 33 References . 35 Global Witness wishes to thank Yayasan HAK, a human rights organisation of Timor Leste, for its help with parts of this report. Cover photo: Beawiharta/Reuters/Corbis Global Witness investigates and exposes the role of natural resource exploitation in funding conflict and corruption. Using first-hand documentary evidence from field investigations and undercover operations, we name and shame those exploiting disorder and state failure. We lobby at the highest levels for a joined-up international approach to manage natural resources transparently and equitably. We have no political affiliation and are non-partisan everywhere we work. Global Witness was co-nominated for the 2003 Nobel Peace Prize for our work on conflict diamonds. ISBN 0-9753582-8-6 This report is the copyright of Global Witness, and may not be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the organisation, except by those who wish to use it to further the protection of human rights and the environment. -

Species Richness of Yapen Island for Sustainable Living Benefit in Papua, Indonesia

ECOLOGICAL ENGINEERING & ENVIRONMENTAL TECHNOLOGY Ecological Engineering & Environmental Technology 2021, 22(1), 92–99 Received: 2020.12.11 https://doi.org/10.12912/27197050/132090 Accepted: 2020.12.28 ISSN 2719-7050, License CC-BY 4.0 Published: 2021.01.05 Species Richness of Yapen Island for Sustainable Living Benefit in Papua, Indonesia Anton Silas Sinery1,3, Jonni Marwa1, Agustinus Berth Aronggear2, Yohanes Yosep Rahawarin1, Wolfram Yahya Mofu1, Reinardus Liborius Cabuy1* 1 Department of Forestry, Faculty of Forestry, University of Papua, Jl. Gunung Salju Amban, Manokwari, West Papua Province, Indonesia 2 Papua Forestry and Conservation Service, Jl. Tanjung Ria, Jayapura Papua Province, Indonesia 3 Environmental Study Center, University of Papua, Jl. Gunung Salju Amban, Manokwari, West Papua Province, Indonesia * Corresponding author’s email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The objective of this study was to precisely identify the types of forest resources utilization in two local communi- ties. All forest plants used were identified and classified based on their types and classes during data collection. Semi-structural interviews through questionnaires were undertaken to obtain daily information. The results showed that there were a total of 64 forest plant life forms and categories extracted for various reasons. Most of the subject forest plants were found in the surrounding lowland tropical forest, the dominant categories were monocotyledons followed by dicotyledons, pteridophytes, and thallophytes. A strong positive correlation was determined between the frequency of species use and the benefit value that was gained (0.6453), while a strong negative correlation was observed between the value of plant’s benefit and the difficulty of access to those plants (-0.2646). -

National Heroes in Indonesian History Text Book

Paramita:Paramita: Historical Historical Studies Studies Journal, Journal, 29(2) 29(2) 2019: 2019 119 -129 ISSN: 0854-0039, E-ISSN: 2407-5825 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15294/paramita.v29i2.16217 NATIONAL HEROES IN INDONESIAN HISTORY TEXT BOOK Suwito Eko Pramono, Tsabit Azinar Ahmad, Putri Agus Wijayati Department of History, Faculty of Social Sciences, Universitas Negeri Semarang ABSTRACT ABSTRAK History education has an essential role in Pendidikan sejarah memiliki peran penting building the character of society. One of the dalam membangun karakter masyarakat. Sa- advantages of learning history in terms of val- lah satu keuntungan dari belajar sejarah dalam ue inculcation is the existence of a hero who is hal penanaman nilai adalah keberadaan pahla- made a role model. Historical figures become wan yang dijadikan panutan. Tokoh sejarah best practices in the internalization of values. menjadi praktik terbaik dalam internalisasi However, the study of heroism and efforts to nilai. Namun, studi tentang kepahlawanan instill it in history learning has not been done dan upaya menanamkannya dalam pembelaja- much. Therefore, researchers are interested in ran sejarah belum banyak dilakukan. Oleh reviewing the values of bravery and internali- karena itu, peneliti tertarik untuk meninjau zation in education. Through textbook studies nilai-nilai keberanian dan internalisasi dalam and curriculum analysis, researchers can col- pendidikan. Melalui studi buku teks dan ana- lect data about national heroes in the context lisis kurikulum, peneliti dapat mengumpulkan of learning. The results showed that not all data tentang pahlawan nasional dalam national heroes were included in textbooks. konteks pembelajaran. Hasil penelitian Besides, not all the heroes mentioned in the menunjukkan bahwa tidak semua pahlawan book are specifically reviewed. -

Praktik Pengalaman Lapangan Fakultas Keguruan Dan Ilmu Pendidikan SD Negeri Locondong

Praktik Pengalaman Lapangan Fakultas Keguruan dan Ilmu Pendidikan SD Negeri Locondong PENGGUNAAN METODE COOPERATIVE LEARNING DALAM PEMBELAJARAN TEMA 5 PAHLAWANKU SUBTEMA 3 SIKAP KEPAHLAWANAN Nuf Anggraeni*1, Galuh Rahayuni2 Universitas Nahdlatul Ulama Al-Ghazali (UNUGHA) Cilacap Fakultas Keguruan dan Ilmu Pendidikan Program Studi Pendidikan Guru Sekolah Dasar A. Pendahuluan Pembelajaran yang dilakukan pada tema 5 Pahlawanku Subtema 3 Sikap Kepahlawanan Pembelajaran 1 menggunakan model pembelajaran Cooperative Learning. Metode pembelajaran yang digunakan dalam pembelajaran yang digunakan dalam pembelajaran yaitu, Ceramah, Diskusi, Tanya Jawab dan Permainan. Pembelajaran yang dilakukan di kelas IV B dilakukan selama 3 jam pembelajaran, dimana 1 jam pelajaran 35 Menit. Satu pertemuan dilakukan selama 105 Menit untuk kegiatan awal, kegiatan inti dan kegiatan penutup. Jumlah siswa di kelas IV B adalah 20 siswa. Materi yang digunakan menggunakan sumber dan buku siswa dan buku guru Tema 5 Pahlawanku Subtema 3 Sikap Kepahlawanan Pembelajaran 1. Mata pelajaran yang termuat didalamnya yaitu IPA, IPS dan Bahasa Indonesia. Mata pelajaran IPA mengenai materi cermin cembung dan cermin cekung, dan pata pelajaran IPS mengenai materi nama Pahlawan Nasional Indonesia. Mata pelajaran Bahasa Indonesia mengenai materi menulis informasi dari teks non fiksi. Penanganan terhadap siswa yang mengalami kesulitan pada saat pembelajaran adalah mendekati dan memberikan bimbingan kepada siswa secara langsung. Kegaduhan yang ditimbulkan oleh siswa ditangani dengan menggunakan beberapa tepuk semangat jilid dua dan tepuk konsentrasi agar konsentrasi kembali pada pembelajaran. Selain itu pada jumlah siswa yang banyak maka dalam pembelajaran harus menggunakan suara yang keras. B. Pembahasan 1. Materi Pembelajaran yang dilakukan di kelas IV B memuat 3 mata pelajaran yaitu IPA, IPS dan Bahasa Indonesia. -

On the Limits of Indonesia

CHAPTER ONE On the Limits of Indonesia ON July 2, 1998, a little over a month after the resignation of Indonesia’s President Suharto, two young men climbed to the top of a water tower in the heart of Biak City and raised the Morning Star flag. Along with similar flags flown in municipalities throughout the Indonesian province of Irian Jaya, the flag raised in the capital of Biak-Numfor signaled a demand for the political independence of West Papua, an imagined nation comprising the western half of New Guinea, a resource-rich territory just short of Indonesia’s east- ernmost frontier. During the thirty-two years that Suharto held office, ruling through a combination of patronage, terror, and manufactured consent, the military had little patience for such demonstrations. The flags raised by Pap- uan separatists never flew for long; they were lowered by soldiers who shot “security disrupters” on sight.1 Undertaken at the dawn of Indonesia’s new era reformasi (era of reform), the Biak flag raising lasted for four days. By noon of the first day, a large crowd of supporters had gathered under the water tower, where they listened to speeches and prayers, and sang and danced to Papuan nationalist songs. By afternoon, their numbers had grown to the point where they were able to repulse an attack by the regency police, who stormed the site in an effort to take down the flag. Over the next three days, the protesters managed to seal off a dozen square blocks of the city, creating a small zone of West Papuan sovereignty adjoining the regency’s main market and port. -

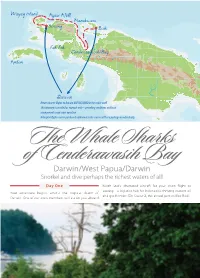

Darwin/West Papua/Darwin Snorkel and Dive Perhaps the Richest Waters of All!

Wayag Island Ayau Atoll Manokwari Sorong Biak Fak Fak Cenderawasih Bay Ambon Darwin Return charter flights ex Darwin ARE INCLUDED in the cruise tariff. This itinerary is provided as example only – prevailing conditions and local arrangements may cause variation. Helicopter flights can be purchased additional to the cruise tariff as a package or individually. TheWhale Sharks of Cenderawasih Bay Darwin/West Papua/Darwin Snorkel and dive perhaps the richest waters of all! Day One North Star’s chartered aircraft for your short flight to Sorong – a logistics hub for Indonesia’s thriving eastern oil Your adventure begins amidst the tropical charm of and gas frontier (On Cruise 2, the arrival port will be Biak). Darwin. One of our crew members will escort you aboard Sorong is also where we will welcome you aboard the spearfishing to collecting eatable worms from the magnificent TRUE NORTH. powdery-white sand beaches. The atoll is surrounded by crystal clear water that is frequented by large pods of Enjoy a welcome aboard cocktail as we begin to cruise dolphins. The outer-reef drops sharply to over 1000m and through the equally magnificent Raja Ampat archipelago. clouds of beautiful fishes carpet the reef walls. We’ll have Located off the northwest tip of Bird’s Head Peninsula a chance to snorkel and dive at several sites around the on the island of New Guinea, in Indonesia’s West Papua atoll, or you can head off to the big-blue (outside the Ayau province, Raja Ampat, or the Four Kings, is an archipelago Marine Park) to try your luck at some deep water trolling. -

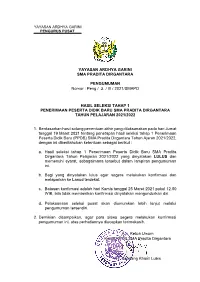

Pengumuman-Tahap-1-Ppdb

YAYASAN ARDHYA GARINI PENGURUS PUSAT YAYASAN ARDHYA GARINI SMA PRADITA DIRGANTARA PENGUMUMAN Nomor : Peng / 2 / III / 2021/SMAPD HASIL SELEKSI TAHAP 1 PENERIMAAN PESERTA DIDIK BARU SMA PRADITA DIRGANTARA TAHUN PELAJARAN 2021/2022 1. Berdasarkan hasil sidang penentuan akhir yang dilaksanakan pada hari Jumat tanggal 19 Maret 2021 tentang penetapan hasil seleksi tahap 1 Penerimaan Peserta Didik Baru (PPDB) SMA Pradita Dirgantara Tahun Ajaran 2021/2022, dengan ini diberitahukan ketentuan sebagai berikut : a. Hasil seleksi tahap 1 Penerimaan Peserta Didik Baru SMA Pradita Dirgantara Tahun Pelajaran 2021/2022 yang dinyatakan LULUS dan memenuhi syarat, sebagaimana tersebut dalam lampiran pengumuman ini. b. Bagi yang dinyatakan lulus agar segera melakukan konfirmasi dan melaporkan ke Lanud terdekat. c. Batasan konfirmasi adalah hari Kamis tanggal 25 Maret 2021 pukul 12.00 WIB, bila tidak memberikan konfirmasi dinyatakan mengundurkan diri. d. Pelaksanaan seleksi pusat akan diumumkan lebih lanjut melalui pengumuman tersendiri. 2. Demikian disampaikan, agar para siswa segera melakukan konfirmasi pengumuman ini, atas perhatiannya diucapkan terimakasih. A.n. Ketua Umum Ketua PPDB SMA Pradita Dirgantara Ny. Sondang Khairil Lubis Lampiran Pengumuman Daftar Nama Peserta Lolos Seleksi Tahap 1 NO KODE DAFTAR NAMA JK ASAL PANDA 1 2 3 4 5 1 PRAK-83JQEKIC Az Zahra Leilany Widjanarka P Lanud Abdul Rachman Saleh (ABD), Malang 2 PRAK-8TM1YQGC Glenn Emmanuel Abraham L Lanud Abdul Rachman Saleh (ABD), Malang 3 PRAK-202101-0879 Kayana Nur Ramadhania P Lanud Abdul -

Comparatives in Melanesia: Concentric Circles of Convergence Antoinette Schapper, Lourens De Vries

Comparatives in Melanesia: Concentric circles of convergence Antoinette Schapper, Lourens de Vries To cite this version: Antoinette Schapper, Lourens de Vries. Comparatives in Melanesia: Concentric circles of conver- gence. Linguistic Typology, De Gruyter, 2018, 22 (3), pp.437-494. 10.1515/lingty-2018-0015. halshs- 02931152 HAL Id: halshs-02931152 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02931152 Submitted on 4 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Linguistic Typology 2018; 22(3): 437–494 Antoinette Schapper and Lourens de Vries Comparatives in Melanesia: Concentric circles of convergence https://doi.org/10.1515/lingty-2018-0015 Received May 02, 2018; revised July 26, 2018 Abstract: Using a sample of 116 languages, this article investigates the typology of comparative constructions and their distribution in Melanesia, one of the world’s least-understood linguistic areas. We present a rigorous definition of a comparative construction as a “comparative concept”, thereby excluding many constructions which have been considered functionally comparatives in Melanesia. Conjoined comparatives are shown to dominate at the core of the area on the island of New Guinea, while (monoclausal) exceed comparatives are found in the maritime regions around New Guinea. -

The West Papua Dilemma Leslie B

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2010 The West Papua dilemma Leslie B. Rollings University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Rollings, Leslie B., The West Papua dilemma, Master of Arts thesis, University of Wollongong. School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2010. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3276 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. School of History and Politics University of Wollongong THE WEST PAPUA DILEMMA Leslie B. Rollings This Thesis is presented for Degree of Master of Arts - Research University of Wollongong December 2010 For Adam who provided the inspiration. TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION................................................................................................................................ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. ii ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................... iii Figure 1. Map of West Papua......................................................................................................v SUMMARY OF ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................... vi INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................1 -

Permissive Residents: West Papuan Refugees Living in Papua New Guinea

Permissive residents West PaPuan refugees living in PaPua neW guinea Permissive residents West PaPuan refugees living in PaPua neW guinea Diana glazebrook MonograPhs in anthroPology series Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/permissive_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Glazebrook, Diana. Title: Permissive residents : West Papuan refugees living in Papua New Guinea / Diana Glazebrook. ISBN: 9781921536229 (pbk.) 9781921536236 (online) Subjects: Ethnology--Papua New Guinea--East Awin. Refugees--Papua New Guinea--East Awin. Refugees--Papua (Indonesia) Dewey Number: 305.8009953 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse. Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2008 ANU E Press Dedicated to the memory of Arnold Ap (1 July 1945 – 26 April 1984) and Marthen Rumabar (d. 2006). Table of Contents List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgements xi Glossary xiii Prologue 1 Intoxicating flag Chapter 1. Speaking historically about West Papua 13 Chapter 2. Culture as the conscious object of performance 31 Chapter 3. A flight path 51 Chapter 4. Sensing displacement 63 Chapter 5. Refugee settlements as social spaces 77 Chapter 6. Inscribing the empty rainforest with our history 85 Chapter 7. Unsated sago appetites 95 Chapter 8. Becoming translokal 107 Chapter 9. Permissive residents 117 Chapter 10. Relocation to connected places 131 Chapter 11. -

Governing New Guinea New

Governing New Guinea New Guinea Governing An oral history of Papuan administrators, 1950-1990 Governing For the first time, indigenous Papuan administrators share their experiences in governing their country with an inter- national public. They were the brokers of development. After graduating from the School for Indigenous Administrators New Guinea (OSIBA) they served in the Dutch administration until 1962. The period 1962-1969 stands out as turbulent and dangerous, Leontine Visser (Ed) and has in many cases curbed professional careers. The politi- cal and administrative transformations under the Indonesian governance of Irian Jaya/Papua are then recounted, as they remained in active service until retirement in the early 1990s. The book brings together 17 oral histories of the everyday life of Papuan civil servants, including their relationship with superiors and colleagues, the murder of a Dutch administrator, how they translated ‘development’ to the Papuan people, the organisation of the first democratic institutions, and the actual political and economic conditions leading up to the so-called Act of Free Choice. Finally, they share their experiences in the UNTEA and Indonesian government organisation. Leontine Visser is Professor of Development Anthropology at Wageningen University. Her research focuses on governance and natural resources management in eastern Indonesia. Leontine Visser (Ed.) ISBN 978-90-6718-393-2 9 789067 183932 GOVERNING NEW GUINEA KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR TAAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE GOVERNING NEW GUINEA An oral history of Papuan administrators, 1950-1990 EDITED BY LEONTINE VISSER KITLV Press Leiden 2012 Published by: KITLV Press Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) P.O.