PAYING for PROTECTION the Freeport Mine and the Indonesian Security Forces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Butcher, W. Scott

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project WILLIAM SCOTT BUTCHER Interviewed by: David Reuther Initial interview date: December 23, 2010 Copyright 2015 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Dayton, Ohio, December 12, 1942 Stamp collecting and reading Inspiring high school teacher Cincinnati World Affairs Council BA in Government-Foreign Affairs Oxford, Ohio, Miami University 1960–1964 Participated in student government Modest awareness of Vietnam Beginning of civil rights awareness MA in International Affairs John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies 1964–1966 Entered the Foreign Service May 1965 Took the written exam Cincinnati, September 1963 Took the oral examination Columbus, November 1963 Took leave of absence to finish Johns Hopkins program Entered 73rd A-100 Class June 1966 Rangoon, Burma, Country—Rotational Officer 1967-1969 Burmese language training Traveling to Burma, being introduced to Asian sights and sounds Duties as General Services Officer Duties as Consular Officer Burmese anti-Indian immigration policies Anti-Chinese riots Ambassador Henry Byroade Comment on condition of embassy building Staff recreation Benefits of a small embassy 1 Major Japanese presence Comparing ambassadors Byroade and Hummel Dhaka, Pakistan—Political Officer 1969-1971 Traveling to Consulate General Dhaka Political duties and mission staff Comment on condition of embassy building USG focus was humanitarian and economic development Official and unofficial travels and colleagues November -

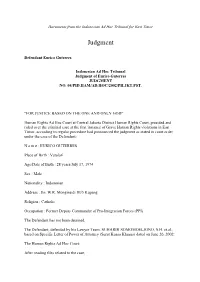

Documents from the Indonesian Ad Hoc Tribunal for East Timor

Documents from the Indonesian Ad Hoc Tribunal for East Timor Judgment Defendant Eurico Guterres Indonesian Ad Hoc Tribunal Judgment of Eurico Guterres JUDGMENT NO. 04/PID.HAM/AD.HOC/2002/PH.JKT.PST. "FOR JUSTICE BASED ON THE ONE AND ONLY GOD" Human Rights Ad Hoc Court at Central Jakarta District Human Rights Court, presided and ruled over the criminal case at the first instance of Grave Human Rights violations in East Timor, according to regular procedure had pronounced the judgment as stated in court order under the case of the Defendant: N a m e : EURICO GUTERRES Place of Birth : Vatolari Age/Date of Birth : 28 years/July 17, 1974 Sex : Male Nationality : Indonesian Address : Jln. W.R. Monginsidi III/5 Kupang Religion : Catholic Occupation : Former Deputy Commander of Pro-Integration Forces (PPI) The Defendant has not been detained. The Defendant, defended by his Lawyer Team: SUHARDI SOMOMOELJONO, S.H. et.al., based on Specific Letter of Power of Attorney (Surat Kuasa Khusus) dated on June 26, 2002: The Human Rights Ad Hoc Court; After reading files related to the case; After reading the Chairman of Human Rights Ad Hoc Court Central Jakarta Decree No.04/PID.HAM/AD.HOC/2002/PH.JKT.PST., dated on June 3, 2002, concerning the appointment of the Judge Panel who presides and rules over the case; After reading the Chairman of Human Rights Ad Hoc Court Central Jakarta Decree No.04/PID.HAM/AD.HOC/2002/PH.JKT.PST., dated on June 20, 2002, concerning the decision on the trial day; After hearing the indicment letter read by the Ad Hoc Prosecuting Attorney, No. -

Timor-Leste's Veterans

Update Briefing Asia Briefing N°129 Dili/Jakarta/Brussels, 18 November 2011 Timor-Leste’s Veterans: An Unfinished Struggle? not solved the problem. Judgment on difficult cases has I. OVERVIEW been deferred based on a belief that fraudulent claims will be revealed through denunciation once the lists are pub- More than ten years after the formation of Timor-Leste’s lished. Even with the option to appeal, new discontent is army and the demobilisation of the guerrilla force that being created that will require mediation. fought for independence, the struggle continues about how to pay tribute to the veterans. The increasingly wealthy state Beyond cash benefits, there are two areas where veterans’ has bought off the threat once posed by most dissidents demands for greater influence will have to be checked. The with an expensive cash benefits scheme and succeeded in first is the scope and shape of a proposed veterans’ council, engaging most veterans’ voices in mainstream politics. This whose primary role will be to consult on benefits as well approach has created a heavy financial burden and a com- as to offer a seal of institutional legitimacy. Some veterans plicated process of determining who is eligible that will hope it will be given an advisory dimension, allowing them create new tensions even as it resolves others. A greater to guide government policy and cementing their elite sta- challenge lies in containing pressures to give them dispro- tus. Such a broad role looks unlikely but the illusion that portionate political influence and a formal security role. veterans might be given more influence has likely in- A careful balance will need to be struck between paying creased the government’s appeal in advance of elections homage to heroes while allowing a younger generation of next year. -

Governing New Guinea New

Governing New Guinea New Guinea Governing An oral history of Papuan administrators, 1950-1990 Governing For the first time, indigenous Papuan administrators share their experiences in governing their country with an inter- national public. They were the brokers of development. After graduating from the School for Indigenous Administrators New Guinea (OSIBA) they served in the Dutch administration until 1962. The period 1962-1969 stands out as turbulent and dangerous, Leontine Visser (Ed) and has in many cases curbed professional careers. The politi- cal and administrative transformations under the Indonesian governance of Irian Jaya/Papua are then recounted, as they remained in active service until retirement in the early 1990s. The book brings together 17 oral histories of the everyday life of Papuan civil servants, including their relationship with superiors and colleagues, the murder of a Dutch administrator, how they translated ‘development’ to the Papuan people, the organisation of the first democratic institutions, and the actual political and economic conditions leading up to the so-called Act of Free Choice. Finally, they share their experiences in the UNTEA and Indonesian government organisation. Leontine Visser is Professor of Development Anthropology at Wageningen University. Her research focuses on governance and natural resources management in eastern Indonesia. Leontine Visser (Ed.) ISBN 978-90-6718-393-2 9 789067 183932 GOVERNING NEW GUINEA KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR TAAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE GOVERNING NEW GUINEA An oral history of Papuan administrators, 1950-1990 EDITED BY LEONTINE VISSER KITLV Press Leiden 2012 Published by: KITLV Press Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) P.O. -

OCEANIA NEWSLETTER No. 100, December 2020 Published Quarterly by the Department of Anthropology and Development Studies, Radboud

OCEANIA NEWSLETTER No. 100, December 2020 Published quarterly by the Department of Anthropology and Development Studies, Radboud University, P.O. Box 9104, 6500 HE Nijmegen, The Netherlands. The website of the newsletter is at: https://www.ru.nl/caos/cpas/publications/oceania-newsletter/. At this site you can download old and new issues of the newsletter in PDF-format. To receive or to stop receiving this newsletter in Word-format, contact the us at [email protected]. Our online database is at http://cps.ruhosting.nl/CPAS/public/index/. This database contains information on Pacific literature that has been listed in the issues of the Oceania Newsletter since 1993. From 1993 backwards we are adding titles of articles and books that have appeared and were reviewed in journals that supply anthropological information on the Pacific. The Pacific is Indigenous Australia, Melanasia, Micronesia and Polynesia. Literature on Asia is not included. CONTENTS 1. The "Third Expedition" to South New Guinea - A Review Essay 1-6 - by Anton Ploeg 2. Amua-gaig-e: The Ethnobotany of the Amungme of Papua, Indonesia - A Review 7-8 - by Anton Ploeg 3. Journal of New Zealand and Pacific Studies, 8(1), 2020: Table of Contents 8-10 4. New Books 10-22 5. Recent Publications 22-33 1. THE "THIRD EXPEDITION" TO SOUTH NEW GUINEA - A REVIEW ESSAY - by Anton Ploeg Versteeg, Gerard Martinus. 2020. Derde Zuid Nieuw-Guinea expeditie 1912-1913: Dagboek van Gerard Martinus Versteeg, arts [The Third South New-Guinea Expedition 1912-1913: Diary of Gerard Martinus Versteeg, Physician], Vol. I and II. -

Update Briefing Asia Briefing N°129 Dili/Jakarta/Brussels, 18 November 2011 Timor-Leste’S Veterans: an Unfinished Struggle?

Update Briefing Asia Briefing N°129 Dili/Jakarta/Brussels, 18 November 2011 Timor-Leste’s Veterans: An Unfinished Struggle? not solved the problem. Judgment on difficult cases has I. OVERVIEW been deferred based on a belief that fraudulent claims will be revealed through denunciation once the lists are pub- More than ten years after the formation of Timor-Leste’s lished. Even with the option to appeal, new discontent is army and the demobilisation of the guerrilla force that being created that will require mediation. fought for independence, the struggle continues about how to pay tribute to the veterans. The increasingly wealthy state Beyond cash benefits, there are two areas where veterans’ has bought off the threat once posed by most dissidents demands for greater influence will have to be checked. The with an expensive cash benefits scheme and succeeded in first is the scope and shape of a proposed veterans’ council, engaging most veterans’ voices in mainstream politics. This whose primary role will be to consult on benefits as well approach has created a heavy financial burden and a com- as to offer a seal of institutional legitimacy. Some veterans plicated process of determining who is eligible that will hope it will be given an advisory dimension, allowing them create new tensions even as it resolves others. A greater to guide government policy and cementing their elite sta- challenge lies in containing pressures to give them dispro- tus. Such a broad role looks unlikely but the illusion that portionate political influence and a formal security role. veterans might be given more influence has likely in- A careful balance will need to be struck between paying creased the government’s appeal in advance of elections homage to heroes while allowing a younger generation of next year. -

New Guinea Highland Wild Dogs Are the Original New Guinea Singing Dogs

New Guinea highland wild dogs are the original New Guinea singing dogs Suriani Surbaktia,1, Heidi G. Parkerb,1, James K. McIntyrec, Hendra K. Maurya, Kylie M. Cairnsd, Meagan Selvige, Margaretha Pangau-Adama,e, Apolo Safonpoa, Leonardo Numberia, Dirk Y. P. Runtuboia, Brian W. Davisf,2, and Elaine A. Ostranderb,2 aDepartment of Biology, Universitas Cenderawasih, Jayapura, Papua 99224, Indonesia; bNational Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda MD 20892; cNew Guinea Highland Wild Dog Foundation, Fernandina Beach, FL 32034; dCentre for Ecosystem Science, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia; eDepartment of Conservation Biology, University of Göttingen, 37073 Göttingen Germany; and fDepartment of Veterinary Integrative Biosciences, Texas A&M University College of Veterinary Medicine, College Station, TX 77843 Contributed by Elaine A. Ostrander, July 17, 2020 (sent for review April 16, 2020; reviewed by Klaus-Peter Koepfli, Fernando Racimo, and Robert D. Schnabel) New Guinea singing dogs (NGSD) are identifiable by their name- on the island. NGSD were first described following collection of sake vocalizations, which are unlike any other canid population. a specimen at an altitude of about 2,100 m in Central Province, Their novel behaviors and potential singular origin during dog PNG, in 1897 (9, 10). Originally classified as a distinct species, domestication make them an attractive, but elusive, subject for Canis hallstromi, their taxonomy remains controversial in part evolutionary and conservation study. Although once plentiful on due to the availability of only captive specimens for genetic the island of New Guinea (NG), they were presumed to currently analysis and debate regarding their origin (3, 10, 11). -

Strike-Slip Faulting in the Core of the Central Range of West New Guinea: Ertsberg Mining District, Indonesia

Strike-slip faulting in the core of the Central Range of west New Guinea: Ertsberg Mining District, Indonesia Benyamin Sapiie² Mark Cloos³ Department of Geological Sciences, University of Texas, Austin, Texas 78712, USA ABSTRACT The change from tens of kilometers of major questions are addressed: (1) What are shortening deformation that caused large- the types, patterns, and distributions of Most of the Cenozoic tectonic evolution scale folding to a few kilometers of left- outcrop-scale structures? (2) What is the re- of the New Guinea region is the result of lateral strike-slip faulting occurred during lationship between deformation and the em- obliquely convergent motion that led to an the latest stage of collisional orogenesis. Al- placement of intrusive rocks, particularly the arc-continent collision between the Paci®c though strike-slip faulting was a minor late- Grasberg Igneous ComplexÐthe host of a su- and Australian plates. Detailed structural stage process, it was of profound impor- pergiant Cu-Au porphyry copper±type ore de- mapping was conducted along road expo- tance in generating pathways for magma posit. The data presented in this paper come sures in the Ertsberg (Gunung Bijih) Min- ascent and permeability for the rise of min- from detailed analysis of structures exposed ing District in the core of the Central Range eralizing ¯uids. The Grasberg Igneous along the 10-km-long Heavy Equipment Ac- in the western half of the island. Two dis- Complex, the host of a supergiant Cu-Au cess Trail (HEAT; called the HEAT Road here- tinct stages of deformation are recognized. porphyry copper±type ore deposit, was em- in) and the 5-km-long Grasberg mining access The ®rst stage took place between ca. -

Christianity, Islam, and Nationalism in Indonesia

Christianity, Islam, and Nationalism in Indonesia As the largest Muslim country in the world, Indonesia is marked by an extraordinary diversity of languages, traditions, cultures, and religions. Christianity, Islam, and Nationalism in Indonesia focuses on Dani Christians of West Papua, providing a social and ethnographic history of the most important indigenous population in the troubled province. It presents a captivating overview of the Dani conversion to Christianity, examining the social, religious, and political uses to which they have put their new religion. Farhadian provides the first major study of a highland Papuan group in an urban context, which distinguishes it from the typical highland Melanesian ethnography. Incorporating cultural and structural approaches, the book affords a fascinating look into the complex relationship among Christianity, Islam, nation making, and indigenous traditions. Based on research over many years, Christianity, Islam, and Nationalism in Indonesia offers an abundance of new material on religious and political events in West Papua. The book underlines the heart of Christian–Muslim rivalries, illuminating the fate of religion in late-modern times. Charles E. Farhadian is Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Westmont College, Santa Barbara, California. Routledge Contemporary Southeast Asia Series 1 Land Tenure, Conservation and Development in Southeast Asia Peter Eaton 2 The Politics of Indonesia–Malaysia Relations One kin, two nations Joseph Chinyong Liow 3 Governance and Civil Society in Myanmar Education, health and environment Helen James 4 Regionalism in Post-Suharto Indonesia Edited by Maribeth Erb, Priyambudi Sulistiyanto, and Carole Faucher 5 Living with Transition in Laos Market integration in Southeast Asia Jonathan Rigg 6 Christianity, Islam, and Nationalism in Indonesia Charles E. -

Charging Ahead Responsibly

2020 ANNUAL REPORT ON SUSTAINABILITY / 3 CHARGING AHEAD RESPONSIBLY. RELIABLY. RELENTLESSLY. 2020 ANNUAL REPORT ON SUSTAINABILITY ABOUT FREEPORT-MCMORAN Freeport-McMoRan Inc. (Freeport-McMoRan, Freeport or FCX) is a leading international mining company with headquarters in Phoenix, Arizona. FCX operates large, long-lived, geographically diverse assets with significant proven and probable reserves of copper, gold and molybdenum. FCX’s portfolio of assets includes the Grasberg minerals district in Indonesia (PT Freeport Indonesia or PT-FI), one of the world’s largest copper and gold deposits; and significant mining operations in North America and South America (Freeport Minerals Corporation or FMC), including the large-scale Morenci minerals district in Arizona and the Cerro Verde operation in Peru. RECENT AWARDS & RECOGNITION Freeport was named to Fortune magazine’s 2021 World’s Most Admired Companies list and ranked No. 6 in its industry category. Forbes magazine ranked Freeport on its 2020 World’s Best Employers List (No. 338), 2020 America’s Best Employer by State (No. 16) and 2020 Best Employers for Diversity (No. 458). Newsweek named Freeport as one of America’s 300 Most Responsible Companies. Points of Light named Freeport to the 2020 The Civic 50 list, recognizing the 50 most community-minded companies in the U.S. for the eighth year in a row and was selected as the Materials Sector Leader. Freeport was named to Forbes magazine’s 2020 JUST 100 as one of America’s most JUST Companies (first in Basic Resources and No. 43 nationally). Cover Photo: Our El Abra operations in Chile implemented Chile's voluntary gender equality ordinance to support increased representation in the workforce. -

Evaluation of UNHCR's Repatriation and Reintegration Programme In

UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES EVALUATION AND POLICY ANALYSIS UNIT Evaluation of UNHCR’s repatriation and reintegration programme in East Timor, 1999-2003 By Chris Dolan, Email: [email protected], EPAU/2004/02 and Judith Large, Email: [email protected] February 2004 independent consultants, and Naoko Obi, EPAU Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit UNHCR’s Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit (EPAU) is committed to the systematic examination and assessment of UNHCR policies, programmes, projects and practices. EPAU also promotes rigorous research on issues related to the work of UNHCR and encourages an active exchange of ideas and information between humanitarian practitioners, policymakers and the research community. All of these activities are undertaken with the purpose of strengthening UNHCR’s operational effectiveness, thereby enhancing the organization’s capacity to fulfil its mandate on behalf of refugees and other displaced people. The work of the unit is guided by the principles of transparency, independence, consultation, relevance and integrity. Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Case Postale 2500 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland Tel: (41 22) 739 8249 Fax: (41 22) 739 7344 e-mail: [email protected] internet: www.unhcr.org/epau All EPAU evaluation reports are placed in the public domain. Electronic versions are posted on the UNHCR website and hard copies can be obtained by contacting EPAU. They may be quoted, cited and copied, provided that the source is acknowledged. The views expressed in EPAU publications are not necessarily those of UNHCR. The designations and maps used do not imply the expression of any opinion or recognition on the part of UNHCR concerning the legal status of a territory or of its authorities. -

Download This PDF File

Jurnal Bestuur Vol.7, Issue.1, Agustus, 2019 P-ISSN 2302-3783 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (cc-by) Economic Law Creation Beautiful Global Indonesia Liana Endah Susanti Faculty of Law, Universitas Soerjo Ngawi – Indonesia. Email Coresponden: [email protected] Abstract Indonesia is the world 's largest archipelago with 1,904,569 km2 of surface area. A very diverse landscape with a variety of abundance of flora and fauna is a special attraction for foreign tourists. Not only that, the natural wealth in Indonesia 's intestines is also very abundant, as are various minerals and richness from other mining materials. However, a abundance of skilled human capital, both in terms of science and technology mastered, do not complement the plentiful natural resources. This is one of the reasons superpowers should be providing cooperation. PT. PT. Freeport is an clear example of Indonesia 's collaboration in the mining sector with foreign parties. The first contract for Freeport-Indonesia was established in 1967. After the Foreign Investment Law was passed in 1967, Freeport became the first foreign mining firm to operate in Indonesia. But the existence of this partnership was regretted by many because it was perceived to be detrimental to the region. The reason is that so far nobody knows for sure how much gold and silver has been produced from the mining to date. The magnitude of the distribution of mining goods is also not quite good given that Indonesia owns land which is turned into gold fields. There are, in fact, many reports uncovering miserable stories of discrimination by indigenous people around the mining region.