Virgins, Vixens & Viragos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inszenierungen Des Traumerlebens Fiktionale Simulationen Des Träumens in Deutschsprachigen Erzähl- Und Dramentexten (1890 Bis 1930)

Inszenierungen des Traumerlebens Fiktionale Simulationen des Träumens in deutschsprachigen Erzähl- und Dramentexten (1890 bis 1930) Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt dem Rat der Philosophischen Fakultät der Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena von Laura Bergander, Magistra Artium (M. A.) geboren am 9. Juni 1985 in Berlin 2016 Gutachter: 1. Prof. Dr. Stefan Matuschek (Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena) 2. PD Dr. Stephan Pabst (Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena) Vorsitzender der Promotionskommission: Prof. Dr. Lambert Wiesing (Friedrich-Schiller- Universität Jena) Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 1. Februar 2017 Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort Annäherung an das Phänomen des Traumerlebens in der Literatur – thematischer Zugang, 1 Fragestellungen, methodische Vorgehensweise I Systematischer Teil – Traumerleben als Natur- und Kulturphänomen 15 1 Naturphänomen Traum und empirisches Traumerleben 15 2 Schwellenabgrenzungen: Vom Natur- zum Kulturphänomen Traum 21 2.1 Kategorialer Abstand und ontologischer Traumdiskurs 21 2.2 Traum – Literatur: Analogiebildungen und Schnittpunkte 28 II Historischer Teil – Ästhetische Entdeckung des Traumes seit dem 18. Jahrhundert 42 1 Der Traum im Zeitalter der Aufklärung 44 1.1 Zwischen Desinteresse, Faszination und Gefahr: Philosophischer Traumdiskurs, 44 Popularaufklärung, Anthropologie, Erfahrungsseelenkunde 1.2 Siegeszug der Einbildungskraft: Traumdarstellungen von Johann Gottlob Krüger 49 und Georg Christoph Lichtenberg 2 Traumdiskurse seit den 1790er Jahren 57 2.1 Jean Paul und die poetologische Entdeckung des Traumes 57 2.2 Diskursives Umfeld: Naturphilosophie, Traum als Natursprache und 65 animalischer Magnetismus 3 Vom „wachen Träumen“ zum Kontrollverlust und zurück: Literarische Darstellungen 72 des Traumerlebens aus der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts 3.1. Novalis‘ Traum von der blauen Blume in Heinrich von Ofterdingen (1802) 72 3.2. Kreatürliche Abgründe in E.T.A. -

Schiller Zeitreise Mp3, Flac, Wma

Schiller Zeitreise mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Stage & Screen Album: Zeitreise Country: Germany Released: 2016 Style: Ambient, Downtempo, Synth-pop, Trance MP3 version RAR size: 1653 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1691 mb WMA version RAR size: 1681 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 550 Other Formats: AIFF MIDI ASF TTA MOD AA AC3 Tracklist Hide Credits CD1-01 –Schiller Zeitreise I 2:18 CD1-02 –Schiller Schwerelos 6:20 CD1-03 –Schiller The Future III 5:40 Ile Aye CD1-04 –Schiller Mit Stephenie Coker 4:12 Vocals [Uncredited] – Stephenie Coker CD1-05 –Schiller Tiefblau 5:09 Der Tag...Du Bist Erwacht CD1-06 –Schiller Mit Jette von Roth 4:18 Vocals [Uncredited] – Jette von Roth CD1-07 –Schiller Sommerregen 3:43 Playing With Madness CD1-08 –Schiller Mit Mia Bergström 5:01 Vocals [Uncredited] – Mia Bergström Leben...I Feel You CD1-09 –Schiller Mit Heppner* 3:51 Vocals [Uncredited] – Peter Heppner In Der Weite CD1-10 –Schiller 5:32 Vocals [Uncredited] – Anna Maria Mühe CD1-11 –Schiller Ultramarin 4:47 CD1-12 –Schiller Berlin - Moskau 4:33 CD1-13 –Schiller Salton Sea 4:49 CD1-14 –Schiller Mitternacht 4:28 CD1-15 –Schiller Polarstern 4:29 Once Upon A Time CD1-16 –Schiller Backing Vocals [Uncredited] – Carmel Echols, 3:49 Chaz Mason, Samantha Nelson Dream Of You CD1-17 –Schiller Mit Heppner* 3:57 Vocals [Uncredited] – Peter Heppner –Schiller Mit Anna Maria Denn Wer Liebt CD1-18 4:20 Mühe Vocals [Uncredited] – Anna Maria Mühe CD2-01 –Schiller Zeitreise II 4:01 Leidenschaft CD2-02 –Schiller Mit Jaki Liebezeit 4:50 Drums [Uncredited] -

Sexualität – Geschlecht – Affekt

Christa Binswanger Sexualität – Geschlecht – Affekt Gender Studies Christa Binswanger (PD Dr.) ist Kulturwissenschaftlerin und leitet den Fach- bereich Gender und Diversity an der Universität St. Gallen. Ihre Forschungs- schwerpunkte sind u.a. Geschlecht und Sexualität, geschlechtergerechter Spra- che und Affect Studies. Christa Binswanger Sexualität – Geschlecht – Affekt Sexuelle Scripts als Palimpsest in literarischen Erzähltexten und zeitgenössischen theoretischen Debatten Publiziert mit Unterstützung des Schweizerischen Nationalfonds zur Förde- rung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter der Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 4.0 Lizenz (BY-NC-ND). Diese Lizenz erlaubt die private Nutzung, gestattet aber keine Bearbeitung und keine kommerzielle Nutzung. Weitere Informationen fin- den Sie unter https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Um Genehmigungen für Adaptionen, Übersetzungen, Derivate oder Wiederver- wendung zu kommerziellen Zwecken einzuholen, wenden Sie sich bitte an rights@ transcript-verlag.de Die Bedingungen der Creative-Commons-Lizenz gelten nur für Originalmaterial. Die Wiederverwendung von Material aus anderen Quellen (gekennzeichnet mit Quellen- angabe) wie z.B. Schaubilder, Abbildungen, Fotos und Textauszüge erfordert ggf. wei- tere Nutzungsgenehmigungen durch den jeweiligen Rechteinhaber. © 2020 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Umschlaggestaltung: Marlies Löcker, fernbedienen . graphic design bureau Lektorat: Maria Matschuk Korrektorat: Annick Bosshart Druck: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-5168-3 PDF-ISBN 978-3-8394-5168-7 EPUB-ISBN 978-3-7328-5168-3 https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839451687 Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem Papier mit chlorfrei gebleichtem Zellstoff. -

Begleitmaterial Urfaust

Theaterpädagogisches Begleitmaterial 1 Liebe Pädagoginnen und Pädagogen, „Und was fangen wir jetzt mit dem Rest unseres Lebens an? Setzen wir uns hier zur Ruhe und schauen dem Treiben draußen zu? Be- schäftigen wir uns mit der Glasmenagerie?“ Amanda Wingfield wünscht sich für ihre Kinder um jeden Preis eine erfolgreiche Zukunft. Doch sowohl Laura wie Tom kommen mit den an sie gestellten Leistungsanforderungen nicht zurecht. Laura ist extrem schüchtern. Anstatt den teuren Wirtschaftskurs zu besuchen, zieht sie sich lieber in ihre eigene Traumwelt zurück. Stundenlang spielt sie mit ihrer Glastiersammlung und hört alte Schallplatten. Tom arbeitet zwar im Lagerhaus und hält die Familie finanziell über Wasser, träumt aber von einer Karriere als Schriftstel- ler und verbringt jede freie Minute im Kino. Mutter Amanda ist mit seinem Lebenswandel überhaupt nicht einverstanden. Sie bittet ihn, einen Verehrer für Laura einzuladen. Die Verheiratung ihrer Tochter mit einem solventen Partner scheint für sie die letzte Hoffnung im Kampf gegen einen sozialen Abstieg zu sein. Mit Die Glasmenagerie hat Tennessee Williams ein leises Drama ge- schrieben, in dem sich eine Familie durch einen beengenden, sticki- gen Alltag kämpft, der nicht selten im Eskapismus endet. Fliehen wir selbst auch vor der Realität? In welchem Ausmaß müssen wir uns an gesellschaftliche Konventio- nen halten, ohne von ihnen zerbrochen zu werden? Inwieweit liegen die Erfolgschancen der Kinder in den Händen der Eltern? Wie sehr darf man als Eltern in das Leben der eigenen Kinder eingrei- fen, ohne übergriffig zu werden? Mit unserem Begleitmaterial wollen wir Ihnen eine Hilfestellung ge- ben, um sich mit Ihrer Klasse oder Gruppe differenzierter mit der Inszenierung, ihren Hintergründen und den dazu passenden spiel- praktischen Übungen auseinanderzusetzen. -

U.K. Blank Tape Firms

.., :.':... See giant pull -output -up centerfold 08120 t30 Z49GRE E N L YM O'JT L+G Mt kbt t4O'NTY GREENLY C T Y NEWSPAPER 374) ELM LING BEACH CA «eb07 A Billboard Publication The Radio Programming, Music /Record International Newsweek ly June 13. 1981 $3 (U.S.) New Life For WEA Adopts NAIRD, Indie U.K. Blank Tape Firms CX- Encoded Distribs Agree Unite, Fight Levy Lobby By LEO SACKS CBS System By PETER JONES PHILADELPHIA -A dramatic turnaround By ALAN PENCHANSKY & in the fortunes of the National Assn. of Inde- LONDON -A newly orchestrated cam- He says: "We just cannot accept that the JIM McCULLAUGH pendent Record Distributors and Manufac- paign to fight record company demands for home -taping problem is as bad as the CHICAGO -The WEA labels' adoption of turers, reflecting the growing economic health a sizable levy on blank tape in the U.K. to record companies say. It's not home-taping CBS' CX- encoded disk program has pushed of specialty indie labels and their wholesalers, compensate for home taping, is under way in isolation that is responsible for slumping that noise reduction system farther toward marked the organization's 1981 convention, here following the formation of the Tape record sales. Also to blame are high prices, large scale consumer reality. which convened here last Sunday (30). Manufacturers Group (TMG). poor technical quality and artistic quality. Product on all WEA labels -Atlantic, NAIRD, whose convention in Kansas City The fiery new organization is headed by "But it is time the record companies real- Elektra /Asylum, Nonesuch and Warner Bros. -

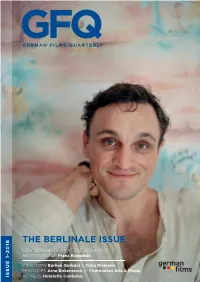

The Berlinale Issue

GFQ GERMAN FILMS QUARTERLY THE BERLINALE ISSUE NEW GERMAN FILMS AT THE BERLINALE SHOOTING STAR Franz Rogowski DIRECTORS Burhan Qurbani & Ziska Riemann PRODUCER Arne Birkenstock of Fruitmarket Arts & Media ISSUE 1-2018 ACTRESS Henriette Confurius CONTENTS GFQ 1-2018 4 5 6 7 8 10 13 16 32 35 36 49 2 GFQ 1-2018 CONTENTS IN THIS ISSUE IN BERLIN NEW DOCUMENTARIES 3 TAGE IN QUIBERON 3 DAYS IN QUIBERON Emily Atef ................. 4 ABHISHEK UND DIE HEIRAT ABHISHEK AND THE MARRIAGE Kordula Hildebrandt .................. 43 IN DEN GÄNGEN IN THE AISLES Thomas Stuber ............................ 5 CLIMATE WARRIORS Carl-A. Fechner, Nicolai Niemann ............... 43 MEIN BRUDER HEISST ROBERT UND IST EIN IDIOT MY BROTHER’S NAME IS ROBERT AND HE IS AN IDIOT Philip Gröning .................... 6 EINGEIMPFT FAMILY SHOTS David Sieveking ................................. 44 TRANSIT Christian Petzold ................................................................ 7 FAREWELL YELLOW SEA Marita Stocker ....................................... 44 DAS SCHWEIGENDE KLASSENZIMMER GLOBAL FAMILY Melanie Andernach, Andreas Köhler .................. 45 THE SILENT REVOLUTION Lars Kraume ......................................... 8 JOMI – LAUTLOS, ABER NICHT SPRACHLOS STYX Wolfgang Fischer ...................................................................... 9 JOMI’S SPHERE OF ACTION Sebastian Voltmer ............................. 45 DER FILM VERLÄSST DAS KINO – VOM KÜBELKIND-EXPERIMENT KINDSEIN – ICH SEHE WAS, WAS DU NICHT SIEHST! UND ANDEREN UTOPIEN FILM BEYOND CINEMA -

Der Petrarkismus – Ein Europäischer Gründungsmythos

Gründungsmythen Europas in Literatur, Musik und Kunst Band 4 herausgegeben von Uwe Baumann, Michael Bernsen und Paul Geyer Michael Bernsen / Bernhard Huss (Hg.) Der Petrarkismus – ein europäischer Gründungsmythos Mit 9 Abbildungen V&R unipress Bonn University Press Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. ISBN 978-3-89971-842-3 ISBN 978-3-86234-842-8 (E-Book) Veröffentlichungen der Bonn University Press erscheinen im Verlag V&R unipress GmbH. 2011, V&R unipress in Göttingen / www.vr-unipress.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk und seine Teile sind urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung in anderen als den gesetzlich zugelassenen Fällen bedarf der vorherigen schriftlichen Einwilligung des Verlages Printed in Germany. Titelbild: Andrea del Sarto: »Dama col Petrarchino«, ca. 1528, Florenz, Galleria degli Uffizi, Wikimedia Commons. Druck und Bindung: CPI Buch Bücher.de GmbH, Birkach Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem Papier. Inhalt Vorwort der Herausgeber . ................... 7 Michael Bernsen Der Petrarkismus, eine lingua franca der europäischen Zivilisation . 15 Stefano Jossa Petrarkismus oder Drei Kronen? Die Ursprünge eines Konfliktes . 31 Catharina Busjan Franciscus Petrarca posteritati salutem: Petrarcas Selbstentwurf und sein Widerhall in den Petrarca-Biographien der Frühen Neuzeit . ...... 51 Martina Meidl »Benedetto sia ’l -

Draculas Vermaechtnis: Technische Schriften

Friedrich Kittler Draculas Vermächtnis Technische Schriften RECLAM VERLAG LEIPZIG ISBN 3-379-01476-1 © Reclam Verlag Leipzig 1993 (für diese Ausgabe) Quellen- und Rechtsnachweis am Schluß des Bandes Reclam-Bibliothek Band 147β 1. Auflage, 1993 Reihengestaltung: Hans Peter Willberg Umschlaggestaltung: Friederike Pondelik unter Verwendung der Computergrafik »Tanz der Silikone« von Werner Drescher Printed in Germany Satz: Schroth Fotosatz GmbH Limbach-Oberfrohna Druck und Binden: Offizin Andersen Nexö Leipzig GmbH Gesetzt aus Meridien Inhalt Vorwort I Draculas Vermächtnis 11 Die V/elt des Symbolischen - eine Welt der Maschine 58 II Romantik - Psychoanalyse - Film: eine Doppelgängergeschichte 81 Benns Gedichte - »Schlager von Klasse« 105 Der Gott der Ohren 130 III Vom Take Off der Operatoren 149 Signal-Rausch-Abstand 161 Real Time Analysis, Time Axis Manipulation 182 Protected Mode 208 Es gibt keine Software 225 Literaturverzeichnis 243 Quellen- und Rechtsnachweis 258 Vorwort Technische Schriften - das besagt nicht nur Schriften über Technik, sondern auch Schriften in der Technik selbst. Ohne diesen Doppelsinn hätte der Aufsatzband seinen stol zen Titel nie gewagt. Leser werden also nicht erfahren, wie Schreibmaschinen zu bauen, Computerprogramme zu schreiben oder Schaltpläne zu lesen sind. Es ist vielmehr - elementarer, aber heikler - der Vorsatz dieser Schriften, »ohne jemals dazu aufgefordert zu sein oder gar das Ziel zu kennen, eine Wissenschaft zu entwickeln, die von techni schen Schriften handelte und doch selbst nicht Technik wäre«'. Diese seltsame Wissenschaft namens Mediengeschichte tut gut daran, unter den vielen Techniken solche zu bevor zugen, die selber schreiben oder lesen. Es geht mithin um Medientechnologien, um Übertragung, Speicherung, Ver arbeitung von-Information. Und die ganze Frage läuft dar auf hinaus, welcher Code welches Medium trägt. -

KITSCH in the PROSE WORKS of THEODOR STORM By

KITSCH IN THE PROSE WORKS OF THEODOR STORM by RACHEL CARNABY, B.A. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Germanic Studies University of Sheffield. March 1985 ABSTRACT RACHEL CARNABY KITSCH IN THE, PROSE WORKS OF THEODOR STORM. The twofold purpose of this study is to clarify, on the one hand, the question of literary evaluation in general and of kitsch in particular, and, on the other, to analyse the prose works of Theodor Storm in the light of the theories of literary evaluation thus established. It therefore follows that the investigation falls into two main sections. The first is in essence theoretical. It consists of seven chapters, in which are examined the terminology, etymology and history of literary evaluation; the many different approaches to tackling and understanding the problem of kitsch (pedagogic, socio—economic, political, religious, moral, philosophical etc.); kitsch in its relationship to art; kitsch in literature and elsewhere (kitsch of both style and philosophy); kitsch and the consumer, especially the female consumer; kitswh's causes and functions under a variety of political and socipa regimeA4.and, lastly, the possible dangers of kitsch and the remedies suggested to help counteract it. The second section commences with a survey of prominent trends in Storm research old and new, followed by an exploration of Storm's awareness of and relationship to his reading public and to his publishers, and the effect on his work of the demands of family finances. Three chapters are devoted specifically to Storm's wide—ranging techniques for appealing to his reading public, and four to one of the most important aspects of his work in relation to kitsch, the women figures and love and marriage in the 'Novellen'. -

Impossible Communities in Prague's German Gothic

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Spring 5-15-2019 Impossible Communities in Prague’s German Gothic: Nationalism, Degeneration, and the Monstrous Feminine in Gustav Meyrink’s Der Golem (1915) Amy Michelle Braun Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, German Literature Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Braun, Amy Michelle, "Impossible Communities in Prague’s German Gothic: Nationalism, Degeneration, and the Monstrous Feminine in Gustav Meyrink’s Der Golem (1915)" (2019). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1809. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/1809 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures Program in Comparative Literature Dissertation Examination Committee: Lynne Tatlock, Chair Elizabeth Allen Caroline Kita Erin McGlothlin Gerhild Williams Impossible Communities in Prague’s German Gothic: Nationalism, Degeneration, and the Monstrous Feminine in Gustav Meyrink’s -

Copyright by Jessica Ellen Plummer 2016

Copyright by Jessica Ellen Plummer 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Jessica Ellen Plummer certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Selling Fiction: the German Colportage Novel 1871-1914 Committee: Kirsten Belgum, Supervisor Sabine Hake Peter Rehberg Kirkland Alex Fulk Michael Winship Selling Fiction: the German Colportage Novel 1871-1914 by Jessica Ellen Plummer, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2016 Dedication For my parents. Acknowledgements Research for this dissertation was supported by generous funding from the University of Texas Germanic Studies Department, the University of Texas Graduate School, summer research grants from the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst and a Max Kade Foundation grant from the American Friends of Marbach. More extensive funding for my research was provided by the Berlin Program for Advanced German and European Studies and an International Dissertation Research Fellowship from the Social Science Research Council. In the course of my work, I was also fortunate to be able to deepen my understanding of book history and the materiality of books thanks to a Directors’ Scholarship from the Rare Book School at the University of Virginia and three- year support of further studies from the Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship in Critical Bibliography. I would like to especially thank the librarians at the German Literature Archive in Marbach who spoke with me time and again about my work, Nicolai Riedel and Jutta Bendt. -

Abiturprüfung 2014 Deutsch, Grundkurs

D GK HT 1 Seite 1 von 3 Name: _______________________ Abiturprüfung 2014 Deutsch, Grundkurs Aufgabenstellung: 1. Analysieren Sie den vorliegenden Textauszug aus dem Werk „Friedrich Schiller oder die Erfindung des Deutschen Idealismus“ von Rüdiger Safranski. Untersuchen Sie dafür den Gedankengang, die Argumentationsstruktur sowie die sprachliche Gestaltung. Erläutern Sie, inwieweit die Form der Darstellung das Anliegen des Autors unterstützt, und beurteilen Sie die Leserwirksamkeit dieses Vorgehens. (42 Punkte) 2. „Ferdinand hat Luise, die er liebt, nicht verstanden“ (Z. 41). Legen Sie, ausgehend von Ihrer Dramenkenntnis, Aspekte der Beziehung zwischen Ferdinand und Luise dar, die zum Verständnis des Zitats notwendig sind, und erläutern Sie Safranskis Behauptung. Prüfen Sie Safranskis These, dass dieses Drama mehr eines über „die Tyrannei des Absolutismus der Liebe“ als ein gesellschaftskritisches Werk sei, und nehmen Sie dazu abschließend Stellung. (30 Punkte) Materialgrundlage: Rüdiger Safranski: Friedrich Schiller oder die Erfindung des Deutschen Idealismus. München; Wien: Hanser 2004, S. 174 – 178 Zugelassene Hilfsmittel: Wörterbuch zur deutschen Rechtschreibung Unkommentierte Ausgabe von Friedrich Schiller „Kabale und Liebe“ (liegt im Prüfungsraum zur Einsichtnahme vor) Nur für den Dienstgebrauch! D GK HT 1 Seite 2 von 3 Name: _______________________ Rüdiger Safranski Friedrich Schiller oder die Erfindung des Deutschen Idealismus (Auszug) Schiller hat in diesem Stück seine eigene Liebesphilosophie auf den Prüfstand gestellt. Macht und Ohnmacht der Liebe ist das eigentliche Thema. Die Frage ist nicht nur, ob eine korrupte Welt die Liebe zerstören kann, sondern auch, ob nicht die Liebe selbst beiträgt zur Korruption der Welt, indem sie ein ausschließliches Eigentum am Anderen fordert. 5 Ferdinand also liebt. Er ist kein Verführer, vielmehr wird er durch seine eigene Liebe ver- führt.