正气歌 the Song of the Spirit of Righteousness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theory and Practice in Language Studies Contents

Theory and Practice in Language Studies ISSN 1799-2591 Volume 8, Number 6, June 2018 Contents REGULAR PAPERS Learning Styles and Motivations for Practicing English as a Foreign Language: A Case Study of 555 Role-play in Two Ecuadorian Universities Jhonny S. Villafuerte, Maria A. Rojas, Sandy L. Hormaza, and Lourdes A. Soledispa Criteria and Scale for Argumentation 564 Chamnong Kaewpet Female Teachers’ Perspectives of Learner Autonomy in the Saudi Context 570 Jameelah Asiri and Nadia Shukri Jordanian Arabic: A Study of the Motivations for the Intentionality in Dialect Change 580 Ahmad M. Saidat Using New Media in Teaching English Reading and Writing for Hearing Impaired Students—Taking 588 Leshan Special Education School as an Example Bo Xu An Analytic Study of Ironic Statements in Ahlam Mistaghanmi’s Their Hearts with Us While Their 595 Bombs Launching towards Us Hayder Tuama Jasim Al-Saedi A Study of Students’ English Cooperative Learning Strategy in the Multimedia Environment 601 Ling Wang The Role of EFL Teacher’s Talk and Identity in Iranian Classroom Context 606 Afsaneh Alijani and Hamed Barjesteh Exploration of the Non-normal Students’ Attitude to Taking Part in the Teacher Qualification 613 Examination in China Lu Gong A Study on English Acquisition from the Perspective of the Multimodal Theory 618 Huaiyu Mu Social Identity and Use of Taboo Words in Angry Mood: A Gender Study 623 Mohammad Hashamdar and Fahimeh Rafi On the Norm Memes in English Translation of Classics—A Case Study of the Translation of the 629 Works by Jiangxi Native -

Captura De Caballos, De Li Qingzhao

Texto y contexto del poema Fu sobre el juego Captura de Caballos, de Li Qingzhao Pilar González España Centro de Estudios de Asia Oriental Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Resumen: Este artículo analiza por primera vez en español el texto y el contexto del poema Fu sobre el juego Captura de Caballos de Li Qingzhao. Se trata de un poema en prosa rimada y ritmada que saca su inspiración de un antiguo juego de ajedrez chino. Resulta de una complejidad extrema, ya que dicho texto, escrito en 1134-1135, parte de normas y principios de estrategia del juego que se combinan con anécdotas y sucesos históricos presentes y pasados, con el fin de aleccionar y divulgar las ideas y opiniones de Li Qingzhao sobre la crítica situación de la época en que vivió. Palabras clave: poesía, fu, juego, China, caballos, historia, Li Qingzhao. Pilar González España es doctora en Filología Hispánica por la Universidad Complutense de Madrid y licenciada en Literatura y Civilización Chinas por la Universidad Michel de Montaigne de Burdeos. Desde 1998 es profesora titular de Pensamiento de Asia Oriental en la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. Entre sus publicaciones destacan: Poesía y pintura de la dinastía Song, Pekín, Chinese Intercontinental Press, 2019; Si Kongtu, 24 categorías de poesía, Madrid, Trotta, 2010; Lu Ji, Wenfu, Madrid, Cátedra, 2010; Wang Wei, Poemas del río Wang, Madrid, Trotta, 2004 (finalista Premio Nacional de Traducción, 2005); Zhuang Zi, Los capítulos interiores, Madrid, Trotta-Unesco, 1998; Li Qingzhao, Poesía completa, Madrid, Ediciones del Oriente y del Mediterráneo, 2010. Correo electrónico: [email protected]. -

“FULL RIVER RED” by Yue Fei Introduction

Primary Source Document with Questions (DBQs) POEM TO BE SUNG TO THE TUNE OF “ FULL RIVER RED” By Yue Fei Introduction In 1127 the Northern Song dynasty came to an end as the Jurchen Liao conquered northern China and drove the Song court south to the Yangzi valley. There, from the capital at Hangzhou, the Song court continued as the Southern Song (1127-1279) to rule southern China. The Southern Song empire was an economically and culturally vibrant place, but the defeat at the hands of non-Chinese Jurchen people and the loss of territory rankled. So did the fact that the court was simply not strong enough to recover the lost territory. Yue Fei (1103-1142) was an officer in the Northern Song army. When the Song retreated south in the face of Jin attacks, Yue Fei opposed the retreat. He continued, however, to serve the emperor, rising to the rank of general and engaging in battles with the Jin and in suppression of peasant uprisings. Yue Fei experienced success in his campaigns against the Jin in 1140. The Southern Song Gaozong Emperor and his advisors, however, sought to make peace with the Jin — which involved returning the northern territories that Yue Fei had just recaptured in his campaigns. Yue Fei and his allies stood in the way of the peace negotiations. Accordingly, Yue Fei was ordered to withdraw — which he did, declaring that “the achievements of ten years have been dashed in a single day.” Yue Fei was arrested on charges of plotting rebellion (charges that his defenders insisted were trumped up) and executed in 1141. -

Representations of History in the Poetry of Zheng Jing Writing About Identity in the Southern Ming

Ming Qing Yanjiu 21 (2017) 58–92 brill.com/mqyj Representations of History in the Poetry of Zheng Jing Writing about Identity in the Southern Ming Olivia Milburn Seoul National University [email protected] Abstract Zheng Jing 鄭經 (1642–1681), the first classically trained Chinese-language poet to write about Taiwan’s landscape, also addressed a number of other themes. This paper will consider his small group of historical poems dealing with the achievements of the founders of earlier imperial dynasties; his poems about contemporary events, in particular the ongoing conflict between the Qing government and the remnants of the Southern Ming dynasty (which he supported) on Taiwan; his poems about his experi- ences as a military commander; and his poems criticizing the Manchu imperial house for their alien customs and culture. These works aren’t read here as straightforwardly autobiographical; instead we’ll interpret them as works of literature, ones carefully constructed to send specific political messages to a contemporary readership. Keywords Zheng Jing – Southern Ming – Ming-Qing transition – poetry – identity – history Introduction In the second half of the seventeenth century, Zheng Jing 鄭經 (1642–1681) became the first classically trained Chinese language poet to write about the landscape of the island of Taiwan. His writings record scenes from the Jinmen and Penghu islands and from Taiwan itself, and he provides the earliest po- etic accounts of the customs and culture of Taiwan’s inhabitants. For this he is justifiably famous within the history of Taiwanese literature. Studies of Zheng © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2018 | doi 10.1163/24684791-12340014Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 11:11:42AM via free access Representations of History in the Poetry of Zheng Jing 59 Jing’s poetry have approached his work from a number of angles. -

La Notion De Zhi Et Ses Corrélats Dans La Culture Chinoise. Une Méthode Pour Conduire Sa Vie

La notion de zhi et ses corr´elatsdans la culture chinoise. Une m´ethode pour conduire sa vie. Manh Trung Ho To cite this version: Manh Trung Ho. La notion de zhi et ses corr´elatsdans la culture chinoise. Une m´ethode pour conduire sa vie.. Anthropologie sociale et ethnologie. Universit´eParis-Diderot - Paris VII, 2011. Fran¸cais. <tel-00690248> HAL Id: tel-00690248 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00690248 Submitted on 22 Apr 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. Université Paris Diderot (Paris 7) Ecole doctorale: Langue, littérature, image : civilisation et sciences humaines Doctorat : Asie Orientale et Sciences Humaines HO Manh Trung La notion de zhi et ses corrélats dans la culture chinoise. Une méthode pour conduire sa vie. Thèse dirigée par Monsieur le Professeur François JULLIEN Soutenue le 29 septembre 2011 JURY : Mr Pierre CHARTIER……..Président Mr François JULLIEN……..Directeur Mr Rémi MATHIEU……..Rapporteur Mr Patrick DOAN………..Rapporteur 2 A mes parents Avec ma piété attendrie. A Monsieur le Professeur François Jullien Avec ma reconnaissance et mon respect. A mon épouse Avec mon amour 3 LA NOTION DE ZHI ET SES CORRELATS DANS LA CULTURE CHINOISE. -

General Index

General Index Italic page numbers indicate that the topic appears in an illustration (along with characters for Chinese, japanese, and Korean authors and or in its caption on the cited page. Authors are listed in this index only works). Chinese, japanese, and Korean characters are provided in this when their ideas or works are discussed; full listings of authors' works index for terms, map titles, people, and works (except for those already as cited in this volume may be found in the Bibliographical Index given in the Bibliographical Index). Abe *$ clan, 581, 582-83, 598 from Ming, 166-67,552,553,554, Nihon henkai ryakuzu, 439 Abe Masamichi rm.r$lE~, 470-71 576,578 plans of Osaka, 418 Abe no Ariyo *1.gflt!t, 582 nautical charts, 53 reconstructed Yoru no tsuki no susumu Abe no Haruchika *$~*Jl, 598 Pei Xiu and, 112, 133 o tadasu no zu, 583 n.9 Abe no Yasutoshi 3($~*Jl, 582 provincial maps, 180 at Saga Prefectural Library, 399 Abe no Yasuyo *$~t!t, 582 reproductions of Ricci's maps, 177 Shinsei tenkyu seisha zu, 598 Abhidharmakosa (Vasubandu), 622, 623, scale on early maps, 54 shitaji chubun no zu, 363 715-16 star map on ceiling of Liao tomb, 549 Shohomaps, 382, 399,400,444 Abma1J4ala (Circle of Water), 716, 718 stone maps, 138 "Tenjiku zu," 376 Aborigines Su Song's star charts, 544-45 Tenmon keito, 590 japanese, 601-2 Suzhou planisphere, 546, 548 Tenmon seisho zu, 590 West Malaysian, 741 Tianjing huowen, 584 Tensho sasei no zu, 598 Accuracy. See also Reality; Representation Xingjing, 529 Takaida bungen ezu, 424 of British map of Burmese -

Representations of History in the Poetry of Zheng Jing Writing About Identity in the Southern Ming

Ming Qing Yanjiu 21 (2017) 58–92 brill.com/mqyj Representations of History in the Poetry of Zheng Jing Writing about Identity in the Southern Ming Olivia Milburn Seoul National University [email protected] Abstract Zheng Jing 鄭經 (1642–1681), the first classically trained Chinese-language poet to write about Taiwan’s landscape, also addressed a number of other themes. This paper will consider his small group of historical poems dealing with the achievements of the founders of earlier imperial dynasties; his poems about contemporary events, in particular the ongoing conflict between the Qing government and the remnants of the Southern Ming dynasty (which he supported) on Taiwan; his poems about his experi- ences as a military commander; and his poems criticizing the Manchu imperial house for their alien customs and culture. These works aren’t read here as straightforwardly autobiographical; instead we’ll interpret them as works of literature, ones carefully constructed to send specific political messages to a contemporary readership. Keywords Zheng Jing – Southern Ming – Ming-Qing transition – poetry – identity – history Introduction In the second half of the seventeenth century, Zheng Jing 鄭經 (1642–1681) became the first classically trained Chinese language poet to write about the landscape of the island of Taiwan. His writings record scenes from the Jinmen and Penghu islands and from Taiwan itself, and he provides the earliest po- etic accounts of the customs and culture of Taiwan’s inhabitants. For this he is justifiably famous within the history of Taiwanese literature. Studies of Zheng © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2018 | doi 10.1163/24684791-12340014Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 09:50:13AM via free access Representations of History in the Poetry of Zheng Jing 59 Jing’s poetry have approached his work from a number of angles. -

The Representation of Military Troops in Pingcheng Tombs and the Private Household Institution of Buqu in Practice

DOI: 10.4312/as.2019.7.2.221-243 221 The Representation of Military Troops in Pingcheng Tombs and the Private Household Institution of Buqu in Practice ∗ Chin-Yin TSENG 22 Abstract In Northern Wei tombs of the Pingcheng period (398–494 CE), we notice a recurrence of the depiction of armed men in both mural paintings and tomb figurines, not in combat but positioned in formation. Consisting of infantry soldiers alongside light and heavy cavalry accompanied by flag bearers, such a military scene presents itself as a point of in- terest amidst the rest of the funerary setting. Is this supposed to be an indication that the tomb occupant had indeed commanded such an impressive set of troops in life? Or had the families commissioned this theme as part of the tomb repertoire simply in hopes of providing protection over the deceased in their life after death? If we set the examination of this type of image against textual history, the household institution of buqu retainers that began as early as the Xin (“New”) Dynasty (9–23 CE) and was codified in the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), serving as private retainer corps of armed men to powerful fami- lies, appears to be the type of social institution reified in the archaeological materials men- tioned above. The large-scale appearance of these military troops inside Pingcheng period tombs might even suggest that with the “tribal policy” in place, the Han Chinese practice of keeping buqu retainers became a convenient method for the Tuoba to manage recently conquered tribal confederations, shifting clan loyalty based on bloodline to household loyalty based on the buqu institution, one with a long social tradition in Chinese history. -

The Record of the Citadel of Sorrows in Literary Chinese

The Record of the Citadel of Sorrows: A case study in Joseon dynasty literature Orion Lethbridge This thesis was submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy of the Australian National University November, 2016 © Copyright by Orion Lethbridge 2016 All Rights Reserved This thesis is my own work. All sources have been acknowledged. November 2016 Acknowledgements This research was made possible by the generous support of the MA Transnational Humanities in Korean Studies Scholarship, funded by the Korean Government (MOE) (AKS-2011-BAA-2106). I would like to extend my deepest thanks to my supervisors, Professor Hyaeweol Choi, Dr Mark Strange, and Dr Roald Maliangkay, for their patience, guidance, and unwavering support. Special thanks are due to Mark, whose painstaking attention to detail and generosity with time and effort were above and beyond the call of duty. I was very fortunate to have been able to participate in the ANU-Hanyang University postgraduate exchange program in Fall Semester 2014, and received invaluable support and language training during my time there. I am also grateful for the feedback that I received when I presented part of this project at the Worldwide Consortium of Korean Studies in June 2016. To Cathy Churchman, Nathan Woolley, Ruth Barraclough, Ksenia Chizhova, Dane Alston, and the many other academic mentors who responded with kindness and encouragement to my random questions, demands, and episodes of fear and doubt, and to countless friends and family members without whose support this would have been impossible: if I were to thank each of you individually, the content of the thesis itself would not fit between the covers, but my sincerest thanks to all of you. -

Theatrical and Fictional Lyricism in Early Qing Literature

Realm of Shadows and Dreams: Theatrical and Fictional Lyricism in Early Qing Literature The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Zhao, Yingzhi. 2014. Realm of Shadows and Dreams: Theatrical and Fictional Lyricism in Early Qing Literature. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12274209 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Realm of Shadows and Dreams: Theatrical and Fictional Lyricism in Early Qing Literature A dissertation presented by Yingzhi Zhao to The Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of East Asian Languages and Civilizations Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May, 2014 ©2014 –Yingzhi Zhao All rights reserved. Professor Wai-yee Li Yingzhi Zhao Realm of Shadows and Dreams: Theatrical and Fictional Lyricism in Early Qing Literature Abstract Early twentieth-century Chinese literary critics create a model of literary development that highlights leading genres for each dynasty. For the Ming and the Qing dynasties, these are drama and fiction. This model relegates other genres of the period, especially poetry and lyric, to a second-class status, and accounts for their less visibility in scholarly research until today. The aim of my dissertation is not to reverse the hierarchy of genres, but to break the boundaries of genres, examining the ways in which the aesthetic sensibility connected to drama and fiction is transposed to other genres and renews their conventions. -

China at War – from Ancient Times to the Modern Day

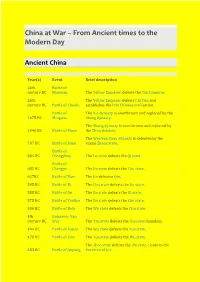

China at War – From Ancient times to the Modern Day Ancient China Year(s) Event Brief description 26th Battle of century BC Banquan The Yellow Emperor defeats the Yan Emperor. 26th The Yellow Emperor defeats Chi You and century BC Battle of Zhuolu establishes the Han Chinese civilisation. Battle of The Xia dynasty is overthrown and replaced by the 1675 BC Mingtiao Shang dynasty. The Shang dynasty is overthrown and replaced by 1046 BC Battle of Muye the Zhou dynasty. The Western Zhou dynasty is defeated by the 707 BC Battle of Xuge vassal Zheng state. Battle of 684 BC Changshao The Lu state defeats the Qi state Battle of 632 BC Chengpu The Jin state defeats the Chu state. 627BC Battle of Xiao The Jin defeates Qin. 595 BC Battle of Bi The Chu state defeats the Jin state. 588 BC Battle of An The Jin state defeats the Qi state. 575 BC Battle of Yanling The Jin state defeats the Chu state. 506 BC Battle of Boju The Wu state defeats the Chu state. 4th Gojoseon–Yan century BC War The Yan state defeats the Gojoseon kingdom. 494 BC Battle of Fujiao The Wu state defeats the Yue state. 478 BC Battle of Lize The Yue state defeats the Wu state. The Zhao state defeats the Zhi state. Leads to the 453 BC Battle of Jinyang Partition of Jin. 353 BC Battle of Guiling The Qi state defeats the Wei state. 342 BC Battle of Maling The Qi state defeats the Wei state. Battle of 341 BC Guailing 293 BC Battle of Yique The Qin state defeats the Wei and Han states. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5033

FOUR / THE ZHONGYI TRADITION OF LOYAL ISTS: WEN TIANXIANG AND THE MARTYRS, 1273-79 Song loyalists of the zhongyi tradition (loyal martyrs) shared one common feature: they died during or shortly after the collapse of Song (1273- 79) because of their personal loyalty to that dynasty. The yimin (remnant sur vivors) are those who survived the dynastic collapse and lived through the early years of Mongol rule, generally in seclusion and without participation in the new government. This chapter is concerned with the first group, and below will first outline the ideological and historical background to the zhongyi loyalists and then present a composite discussion of the group. Next, the careers of Wen Tianxiang, Li Tingzhi, Lu Xiufu, Zhang Shijie, and Xie Fangde are examined separately. The relationships of Wen Tianxiang and Li Tingzhi with the lesser known followers and subordinates are dealt with next, followed by a brief look at the "virtuous women" associated with the zhongyi tradition. Finally, this chapter offers a perspective on some former Song offi cials and generals who defected to the Mongols. Ideological and Historical Background The notion of zhongyi (literally, the loyal and righteous) embraces two fundamental Confucian concepts: loyalty and righteousness (duty or obli gation). Zhong (loyalty) normally describes a subject's allegiance to the ruler and country, but before the Han dynasty (206 B.C.-A. D. 220) it was more often used in a general sense with other shades of meaning: trustworthiness and sincerity, faithfulness to oneself, and reciprocity with superiors and other men.' The reciprocal relationship as hinted in the notion of yi (righteous- 1.