Famine Early Warning System Project U.S. Agency for International

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tcd Str Hno2017 Fr 20161216.Pdf

APERÇU DES 2017 BESOINS HUMANITAIRES PERSONNES DANS LE BESOIN 4,7M NOV 2016 TCHAD OCHA/Naomi Frerotte Ce document est élaboré au nom de l'Equipe Humanitaire Pays et de ses partenaires. Ce document présente la vision des crises partagée par l'Equipe Humanitaire Pays, y compris les besoins humanitaires les plus pressants et le nombre estimé de personnes ayant besoin d'assistance. Il constitue une base factuelle consolidée et contribue à informer la planification stratégique conjointe de réponse. Les appellations employées dans le rapport et la présentation des différents supports n'impliquent pas d'opinion quelconque de la part du Secrétariat de l'Organisation des Nations Unies concernant le statut juridique des pays, territoires, villes ou zones, ou de leurs autorités, ni de la délimitation de ses frontières ou limites géographiques. www.unocha.org/tchad www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/chad @OCHAChad PARTIE I : PARTIE I : RÉSUMÉ Besoins humanitaires et chiffres clés Impact de la crise Personnes dans le besoin Sévérité des besoins 03 PERSONNESPARTIE DANS LEI : BESOIN Personnes dans le besoin par Sites et Camps de déplacement catégorie (en milliers) M Site de retournés 4,7 Population Camp de réfugiés Ressortissants locale de pays tiers Sites/lieux de déplacement interne EGYPTE Personnes xx déplacées Réfugiés MAS supérieur à 2% internes Retournés Phases du Cadre Harmonisé (période projetée, juin-août 2017) LIBYE Minimale (phase 1) Sous pression (phase 2) Crise (phase 3) TIBESTI 13 NIGER ENNEDI OUEST 35 ENNEDI EST BORKOU 82 04 -

Consolidated Appeal Mid-Year Review 2013+

CHAD CONSOLIDATED APPEAL MID-YEAR REVIEW 2013+ A tree provides shelter for a meeting with a community of returnees in Borota, Ouaddai Region. Pierre Peron / OCHA CHAD Consolidated Appeal Mid-Year Review 2013+ CHAD CONSOLIDATED APPEAL MID-YEAR REVIEW 2013+ Participants in 2013 Consolidated Appeal A AFFAIDS, ACTED, Action Contre la Faim, Avocats sans Frontières, C CARE International, Catholic Relief Services, COOPI, NGO Coordination Committee in Chad, CSSI E ESMS F Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations I International Medical Corps UK, Intermon Oxfam, International Organization for Migration, INTERSOS, International Aid Services J Jesuit Relief Services, JEDM, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS M MERLIN O Oxfam Great Britain, Organisation Humanitaire et Développement P Première Urgence – Aide Médicale Internationale S Solidarités International U United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, United Nations Development Programme, UNAD, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, United Nations Population Fund, United Nations Children’s Fund W World Food Programme, World Health Organization. Please note that appeals are revised regularly. The latest version of this document is available on http://unocha.org/cap. Full project details, continually updated, can be viewed, downloaded and printed from http://fts.unocha.org. CHAD CONSOLIDATED APPEAL MID-YEAR REVIEW 2013+ TABLE OF CONTENTS REFERENCE MAP ................................................................................................................................ -

Tcd Map Borkoufr A1l 20210325.Pdf

TCHAD Province du Borkou Mars 2021 15°30'0"E 16°0'0"E 16°30'0"E 17°0'0"E 17°30'0"E 18°0'0"E 18°30'0"E 19°0'0"E 19°30'0"E 20°0'0"E 20°30'0"E Goho Mademi Tomma Zizi Sano Diendaleme Madagala Mangara Dao Tiangala Louli Kossamanga Adi-Ougini Enneri Foditinga Massif de Nangara Dao Aorounga N I G E R Enneri Tougoui Yi- Gaalinga Baudrichi Agalea Madagada Enneri Maleouni Ehi Ooyi Tei Trama Aite Illoum Goa Yasko Daho-Mountou Kahor Doda Gerede Meskou Ounianga Tire Medimi Guerede Enneri Tougoul Ounianga-Kebir TIBESTI EST Moiri Achama Ehine Sata Tega Bezze Edring Tchige Kossamanga OmanKatam Garda-Goulji Ourede Ounianga-Kebir Fochimi Borkanga Nandara Enneri Tamou 19°0'0"N Sabka 19°0'0"N Chiede Ourti Tchigue Kossamanga Enneri Bomou Bellah Erde Bellah Koua Ehi Kourri Kidi Bania Motro Kouroud Bilinga Ehi Kouri Ounianga Serir Ouichi Kouroudi Ouassar Ehi Sao Doma Douhi Ihe Yaska Terbelli Tebendo Erkou T I B E S T I Soeka Latma Tougoumala Ehi Ouede-Ouede Saidanga Aragoua Nodi Tourkouyou Erichi Enneri Chica Chica Bibi Dobounga Ehi Guidaha Zohur Gouri Binem Arna Orori Ehi Gidaha Gouring TIBESTI OUEST Enneri Krema Enneri Erkoub Mayane An Kiehalla Sole Somma Maraho Rond-Point de Gaulle Siniga Dozza Lela Tohil Dian Erde Kourditi Eddeki Billi Chelle Tigui Arguei Bogarna Marfa Ache Forom Oye Yeska FADA Kazer Ehi Echinga Tangachinga Edri Boughi Loga Douourounga Karda Dourkou Bina Kossoumia Enneri Sao Doma Localités Enneri Akosmanoa Yarda Sol Sole Choudija Assoe Eberde Madadi Enneri Nei Tiouma Yarda Bedo Rou Abedake Oue-Oue Bidadi Chef-lieu de province 18°30'0"N -

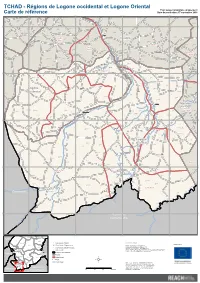

Régions De Logone Occidental Et Logone Oriental

TCHAD - Régions de Logone occidental et Logone Oriental Pour usage humanitaire uniquement Carte de référence Date de production: 07 septembre 2018 15°30'0"E 16°0'0"E 16°30'0"E 17°0'0"E Gounou Koré Marba Kakrao Ambasglao Boudourr Oroungou Gounaye Djouman Goubou Gabrigué Tagal I Drai Mala Djoumane Disou Kom Tombouo Landou Marba Gogor Birem Dikna Goundo Nongom Goumga Zaba I Sadiki Ninga Pari N N " Baktchoro Narégé " 0 0 ' Pian Bordo ' 0 0 3 Bérem Domo Doumba 3 ° ° 9 Brem 9 Tchiré Gogor Toguior Horey Almi Zabba Djéra Kolobaye Kouma Tchindaï Poum Mbassa Kahouina Mogoy Gadigui Lassé Fégué Kidjagué Kabbia Gounougalé Bagaye Bourmaye Dougssigui Gounou Ndolo Aguia Tchilang Kouroumla Kombou Nergué Kolon Laï Batouba Monogoy Darbé Bélé Zamré Dongor Djouni Koubno Bémaye Koli Banga Ngété Tandjile Goun Nanguéré Tandjilé Dimedou Gélgou Bongor Madbo Ouest Nangom Dar Gandil Dogou Dogo Damdou Ngolo Tchapadjigué Semaïndi Layane Béré Delim Kélo Dombala Tchoua Doromo Pont-Carol Dar Manga Beyssoa Manaï I Baguidja Bormane Koussaki Berdé Tandjilé Est Guidari Tandjilé Guessa Birboti Tchagra Moussoum Gabri Ngolo Kabladé Kasélem Centre Koukwala Toki Béro Manga Barmin Marbelem Koumabodan Ter Kokro Mouroum Dono-Manga Dono Manga Nantissa Touloum Kalité Bayam Kaga Palpaye Mandoul Dalé Langué Delbian Oriental Tchagra Belimdi Kariadeboum Dilati Lao Nongara Manga Dongo Bitikim Kangnéra Tchaouen Bédélé Kakerti Kordo Nangasou Bir Madang Kemkono Moni Bébala I Malaré Bologo Bélé Koro Garmaoa Alala Bissigri Dotomadi Karangoye Dadjilé Saar-Gogne Bala Kaye Mossoum Ngambo Mossoum -

Myr 2010 Chad.Pdf

ORGANIZATIONS PARTICIPATING IN CONSOLIDATED APPEAL CHAD ACF CSSI IRD UNDP ACTED EIRENE Islamic Relief Worldwide UNDSS ADRA FAO JRS UNESCO Africare Feed the Children The Johanniter UNFPA AIRSERV FEWSNET LWF/ACT UNHCR APLFT FTP Mercy Corps UNICEF Architectes de l’Urgence GOAL NRC URD ASF GTZ/PRODABO OCHA WFP AVSI Handicap International OHCHR WHO BASE HELP OXFAM World Concern Development Organization CARE HIAS OXFAM Intermon World Concern International CARITAS/SECADEV IMC Première Urgence World Vision International CCO IMMAP Save the Children Observers: CONCERN Worldwide INTERNEWS Sauver les Enfants de la Rue International Committee of COOPI INTERSOS the Red Cross (ICRC) Solidarités CORD IOM Médecins Sans Frontières UNAIDS CRS IRC (MSF) – CH, F, NL, Lux TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................................. 1 Table I: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by cluster) ................................................... 3 Table II: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by appealing organization).......................... 4 Table III: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by priority)................................................... 5 2. CHANGES IN THE CONTEXT, HUMANITARIAN NEEDS AND RESPONSE ........................................... 6 3. PROGRESS TOWARDS ACHIEVING STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES AND SECTORAL TARGETS .......... 9 3.1 STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................................ -

République Du Tchad

Enquête Nationale Post-récoltes sur la Sécurité Alimentaire des Ménages Ruraux du Tchad République du Tchad Février 2012 Données de novembre/décembre 2011 Enquête Nationale post-récoltes sur la Sécurité Alimentaire des ménages ruraux du Tchad Pour plus d’informations, contacter : Bureau de pays du PAM Tchad Unité VAM/M&E, Section Programme : [email protected] Anne-Claire Mouilliez, Bureau du PAM Tchad: [email protected] Wilfred Nkwambi, Bureau du PAM Tchad: [email protected] © Programme Alimentaire Mondial, Service de l’Analyse de la Sécurité Alimentaire (VAM), février 2012 Programme alimentaire mondial des Nations Unies (PAM) Siège social : Via C.G. Viola 68, Parco de Medici, 00148, Rome, Italie Toutes les informations sur le service de l’Analyse de la Sécurité Alimentaire (VAM) et les rapports en format électronique sur http://www.wfp.org/food-security ou [email protected] 2 Table des matières LISTE DES TABLEAUX ................................................................................................................................................ 6 LISTE DES FIGURES .................................................................................................................................................... 6 LISTE DES CARTES ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 LISTE DES ANNEXES .................................................................................................................................................. -

Lake Chad Basin

Integrated and Sustainable Management of Shared Aquifer Systems and Basins of the Sahel Region RAF/7/011 LAKE CHAD BASIN 2017 INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION EDITORIAL NOTE This is not an official publication of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The content has not undergone an official review by the IAEA. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the IAEA or its Member States. The use of particular designations of countries or territories does not imply any judgement by the IAEA as to the legal status of such countries or territories, or their authorities and institutions, or of the delimitation of their boundaries. The mention of names of specific companies or products (whether or not indicated as registered) does not imply any intention to infringe proprietary rights, nor should it be construed as an endorsement or recommendation on the part of the IAEA. INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION REPORT OF THE IAEA-SUPPORTED REGIONAL TECHNICAL COOPERATION PROJECT RAF/7/011 LAKE CHAD BASIN COUNTERPARTS: Mr Annadif Mahamat Ali ABDELKARIM (Chad) Mr Mahamat Salah HACHIM (Chad) Ms Beatrice KETCHEMEN TANDIA (Cameroon) Mr Wilson Yetoh FANTONG (Cameroon) Mr Sanoussi RABE (Niger) Mr Ismaghil BOBADJI (Niger) Mr Christopher Madubuko MADUABUCHI (Nigeria) Mr Albert Adedeji ADEGBOYEGA (Nigeria) Mr Eric FOTO (Central African Republic) Mr Backo SALE (Central African Republic) EXPERT: Mr Frédèric HUNEAU (France) Reproduced by the IAEA Vienna, Austria, 2017 INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION Table of Contents 1. -

Chad: Defusing Tensions in the Sahel

Chad: Defusing Tensions in the Sahel $IULFD5HSRUW1 _ 'HFHPEHU 7UDQVODWLRQIURP)UHQFK +HDGTXDUWHUV ,QWHUQDWLRQDO&ULVLV*URXS $YHQXH/RXLVH %UXVVHOV%HOJLXP 7HO )D[ EUXVVHOV#FULVLVJURXSRUJ Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Ambivalent Relations with N’Djamena ............................................................................ 3 A. Relations between the Sahel Regions and Central Government since the 1990s ..... 3 1. Kanem ................................................................................................................... 3 2. Bahr el-Ghazal (BEG) ........................................................................................... 5 B. C0-option: A Flawed Strategy .................................................................................... 6 III. Mounting Tensions in the Region .................................................................................... 8 A. Abuses against BEG and Kanem Citizens .................................................................. 8 B. A Regional Economy in the Red ................................................................................ 9 C. Intra-religious Divides ............................................................................................... 11 IV. The -

Lake Chad Basin Crisis Regional Market Assessment June 2016 Data Collected January – February 2016

Lake Chad Basin Crisis Regional Market Assessment June 2016 Data collected January – February 2016 Acknowledgments This study was prepared by Stephanie Brunelin and Simon Renk. Primary data was collected in collaboration with ACF and other partners, under the overall supervision of Simon Renk. Acknowledgments go to Abdoulaye Ndiaye for the maps and to William Olander for cleaning the survey data. The mission wishes to acknowledge valuable contributions made by various colleagues in WFP country office Chad and WFP Regional Bureau Dakar. Special thanks to Cecile Barriere, Yannick Pouchalan, Maggie Holmesheoran, Patrick David, Barbara Frattaruolo, Ibrahim Laouali, Mohamed Sylla, Kewe Kane, Francis Njilie, Analee Pepper, Matthieu Tockert for their detailed and useful comments on earlier versions of the report. The report has also benefitted from the discussions with Marlies Lensink, Malick Ndiaye and Salifou Sanda Ousmane. Finally, sincere appreciation goes to the enumerators, traders and shop-owners for collecting and providing information during the survey. Acronyms ACF Action Contre la Faim ACLED Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project FAO Food and Agriculture Organization FEWS NET Famine Early Warning System Network GDP Gross Domestic Product GPI Gender Parity Index IDP Internally Displaced People IFC International Finance Corporation IMF International Monetary Fund IOM International Organization for Migration MT Metric Ton NAMIS Nigeria Agricultural Market Information Service OHCHR Office of the United Nations High Commissioner -

Chapter 1 Present Situation of Chad's Water Development and Management

1 CONTEXT AND DEMOGRAPHY 2 With 7.8 million inhabitants in 2002, spread over an area of 1 284 000 km , Chad is the 25th largest 1 ECOSI survey, 95-96. country in Africa in terms of population and the 5th in terms of total surface area. Chad is one of “Human poverty index”: the poorest countries in the world, with a GNP/inh/year of USD 2200 and 54% of the population proportion of households 1 that cannot financially living below the world poverty threshold . Chad was ranked 155th out of 162 countries in 2001 meet their own needs in according to the UNDP human development index. terms of essential food and other commodities. The mean life expectancy at birth is 45.2 years. For 1000 live births, the infant mortality rate is 118 This is in fact rather a and that for children under 5, 198. In spite of a difficult situation, the trend in these three health “monetary poverty index” as in reality basic indicators appears to have been improving slightly over the past 30 years (in 1970-1975, they were hydraulic infrastructure respectively 39 years, 149/1000 and 252/1000)2. for drinking water (an unquestionably essential In contrast, with an annual population growth rate of nearly 2.5% and insufficient growth in agricultural requirement) is still production, the trend in terms of nutrition (both quantitatively and qualitatively) has been a constant insufficient for 77% of concern. It was believed that 38% of the population suffered from malnutrition in 1996. Only 13 the population of Chad. -

Province Du Ouaddai Octobre 2019

TCHAD Province du Ouaddai Octobre 2019 20°0'0"E 20°30'0"E 21°0'0"E 21°30'0"E 22°0'0"E G G Dicker Kineda Kolonga G GFarey Angara G GGorane G Malanga Koïbo G G Kassiné W A D I F I R A GMiti Miti GKour Kouré GDouguine Abtoboye Erné G Am-Zoer G Guérry GAmhitane GTerkeme G Bourtail Mata Baibor G Localités Capitale Chef-Lieu de province GDjimeze N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 Chef-Lieu de département ° ° 4 Krey 4 1 G 1 Doulbarid Chef-Lieu de sous-préfecture G GH. Doukour GKoudouguine Magare Camp de réfugiés Mabrone G Site de déplacés/retournés Village hôte Kawa G Infrastructures G GTaïba G Kamina Centre de santé/Hopital AEB G GG G G Djatinié G Aérodrome Salamat Abéché Barout GMoura G Tourané GTraoné Piste d'atterrissage Gaga Amleyouna G G Route principale Mabrouka G Fochi G Route secondaire GHadjilidje Erlé MG olou Piste Limites administratives G Abougoudam Frontière nationale Abougoulegne Djazire Tama G Limite de province G GDop-Dop Farchana G Limite de département GKidjimira Hilouta G GMarchout Hydrographie Plan d'eau N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 Abhkouta 0 3 G 3 ° ° 3 BATHA EST 3 1 1 G Bredjing GAdré GTongori Adre G Treguine GHadjer-Hadid G Hadjer-Hadid DjoroGko MahamataG Rimele G O U A D D A I G Chokoyan B A T H A MG arfa LIBYE GAndokone Tibesti Mourdiguine GAssartni G NIGER Abkar-Djombo GHougoune GArkoum Goungour Ennedi Ouest G Abkar G GKatafa Ennedi Est Borkou Goundiang G S O U D A N Kouchkouchné G Kanem Wadi Fira GAllacha GAtarak Barh-El-Gazel Batha SOUDAN Hileket Lac GMargachagane G Ouaddaï Hadjer-Lamis GAmdeguigue N'Djaména Sila NIGÉRIA N N " " Chari-Baguirmi -

Chad Food Security Update: July, 2000 Summary 1

Chad Food Security Update: July, 2000 Summary The month of July was characterized by a satisfactory situation overall, in both the Sudanian and Sahelian zones of Chad. Highly food insecure populations in the Sahelian zone constituted an important exception. People there had to intensify their income-generating activities (such as working for others and selling cattle) in order to buy their basic food staples. The agricultural season is underway, although it started late this year in most cantons compared to last year. Pasture conditions are good in the Sudanian zone while the Sahelian zone only started greening up during the third dekad (10-day period) of July. Livestock health is also good. Millet and sorghum prices remain affordable, although higher than prices last year in the Sahelian zone. Prices in Kanem and parts of Ouaddaï Prefectures in the Sahelian zone increased during the past quarter, though this is normal for the pre-harvest period. 1. Agrometeorological Situation The Inter-topical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) oscillates between 17º N and 19º N, between the cities of Fada and Ounianga Kebir (Borkou and Ennedi Sub-prefectures). Large quantities of rainfall were recorded south of the ITCZ during the third dekad of July, notably in the Sahelian zone. According to the Directorate of Water Resources and Meteorology (DREM), total dekadal rainfall during July was less than the rainfall during the same period last year, except for several rain stations. Rainfall during the third dekad exceeded long-term average levels (1961-1990) in most locations. Satellite images analyzed by FEWS NET/Chad corroborate rain station data showing that third dekad rainfall varied between average and very good in the Sahel and Sudanian zones.