Chad Vulnerability Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Visibility How Disaggregated Metrics Help to Reduce Multidimensional Poverty

High Visibility How disaggregated metrics help to reduce multidimensional poverty Sabina Alkire and Gisela Robles Aguilar January 2015 In the digital age, it is becoming ever-easier to take good quality, clear photos to share with family and friends. With new technologies that enable us to zoom in and see vivid detail, photos are no longer low- resolution and blurred. And just as we demand clarity from pictures, so we need high resolution poverty metrics. Ahead of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) beginning in September 2015, policymakers across the world are preparing new ways to confront abject poverty in all its forms. As they seek tools to help them do this most effectively, one thing that they are calling for is ‘disaggregated data’. Using the Winter 2014/2015 MPI estimations, this briefing note demonstrates how disaggregated data provide a more detailed picture of the interlinked conditions of the poorest, so that policies can be most effectively designed and targeted. For poverty varies by sub-national regions, rural and urban areas, and among different population subgroups. Here we analyse poverty by sub-national regions; of course, decompositions by ethnicity and age enrich the picture further (Alkire & Vaz 2014, Vaz 2014). About the global MPI: Updates and coverage in Winter 2014/2015 The global MPI is an international measure of Figure 1: Inside the MPI poverty that combines simultaneous disadvantages experienced by the poor across different areas of their lives, covering education, health and living standards (Alkire and Santos 2014; UNDP 2014, Alkire Conconi Robles and Seth 2015). If a person is deprived in one-third or more of ten weighted indicators, they are identified as multidimensionally poor (Figure 1). -

Tcd Str Hno2017 Fr 20161216.Pdf

APERÇU DES 2017 BESOINS HUMANITAIRES PERSONNES DANS LE BESOIN 4,7M NOV 2016 TCHAD OCHA/Naomi Frerotte Ce document est élaboré au nom de l'Equipe Humanitaire Pays et de ses partenaires. Ce document présente la vision des crises partagée par l'Equipe Humanitaire Pays, y compris les besoins humanitaires les plus pressants et le nombre estimé de personnes ayant besoin d'assistance. Il constitue une base factuelle consolidée et contribue à informer la planification stratégique conjointe de réponse. Les appellations employées dans le rapport et la présentation des différents supports n'impliquent pas d'opinion quelconque de la part du Secrétariat de l'Organisation des Nations Unies concernant le statut juridique des pays, territoires, villes ou zones, ou de leurs autorités, ni de la délimitation de ses frontières ou limites géographiques. www.unocha.org/tchad www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/chad @OCHAChad PARTIE I : PARTIE I : RÉSUMÉ Besoins humanitaires et chiffres clés Impact de la crise Personnes dans le besoin Sévérité des besoins 03 PERSONNESPARTIE DANS LEI : BESOIN Personnes dans le besoin par Sites et Camps de déplacement catégorie (en milliers) M Site de retournés 4,7 Population Camp de réfugiés Ressortissants locale de pays tiers Sites/lieux de déplacement interne EGYPTE Personnes xx déplacées Réfugiés MAS supérieur à 2% internes Retournés Phases du Cadre Harmonisé (période projetée, juin-août 2017) LIBYE Minimale (phase 1) Sous pression (phase 2) Crise (phase 3) TIBESTI 13 NIGER ENNEDI OUEST 35 ENNEDI EST BORKOU 82 04 -

Consolidated Appeal Mid-Year Review 2013+

CHAD CONSOLIDATED APPEAL MID-YEAR REVIEW 2013+ A tree provides shelter for a meeting with a community of returnees in Borota, Ouaddai Region. Pierre Peron / OCHA CHAD Consolidated Appeal Mid-Year Review 2013+ CHAD CONSOLIDATED APPEAL MID-YEAR REVIEW 2013+ Participants in 2013 Consolidated Appeal A AFFAIDS, ACTED, Action Contre la Faim, Avocats sans Frontières, C CARE International, Catholic Relief Services, COOPI, NGO Coordination Committee in Chad, CSSI E ESMS F Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations I International Medical Corps UK, Intermon Oxfam, International Organization for Migration, INTERSOS, International Aid Services J Jesuit Relief Services, JEDM, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS M MERLIN O Oxfam Great Britain, Organisation Humanitaire et Développement P Première Urgence – Aide Médicale Internationale S Solidarités International U United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, United Nations Development Programme, UNAD, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, United Nations Population Fund, United Nations Children’s Fund W World Food Programme, World Health Organization. Please note that appeals are revised regularly. The latest version of this document is available on http://unocha.org/cap. Full project details, continually updated, can be viewed, downloaded and printed from http://fts.unocha.org. CHAD CONSOLIDATED APPEAL MID-YEAR REVIEW 2013+ TABLE OF CONTENTS REFERENCE MAP ................................................................................................................................ -

TCHAD Province Du Salamat Octobre 2019

TCHAD Province du Salamat Octobre 2019 18°30'0"E 19°0'0"E 19°30'0"E 20°0'0"E 20°30'0"E 21°0'0"E 21°30'0"E 22°0'0"E Dadouar G GAm Bourougne Bang-Bang G Bagoua GKofilo G Dogdore GZarli G Golonti ABTOUYOUR G N Mogororo N " " 0 Koukou G 0 ' G Koukou-Angarana ' 0 G G 0 ° ABTOUYOUR Koukou angara ° 2 G 2 1 Niergui Badago G Goz Amir Tioro 1 G Louboutigue G GAbgué GUÉRA GTounkoul MANGALMÉ KerfGi MANGALMÉ Kerfi GUÉRA GIdbo GBandikao GAl Ardel Localités GFoulounga GMouraye Capitale N ABOUDÉIA N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 Chef-Lieu de province 3 3 ° ° 1 1 1 1 Chef-Lieu de département G Aboudéïa GAm-Habilé GAgrab Dourdoura G Chef-Lieu de sous-préfecture GArdo Camp de réfugiés GDarasna Daradir G Site de déplacés/retournés GMirer Village hôte GZarzoura Amdjabir G Infrastructures GLiwi G Centre de santé/Hopital GIdater Aérodrome Piste d'atterrissage Am Karouma G Am-Timan G Route principale N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 G Am Senene 0 ° Goz Djerat ° 1 G 1 Route secondaire 1 1 Piste Zakouma Limites administratives Aoukalé Frontière nationale S A L A M A T Limite de province Limite de département BARH-SIGNAKA Hydrographie GDaguela BARH-SIGNAKA Plan d'eau BAHR-AZOUM Département Chinguil G GKieke N Zane N " G " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 3 3 ° GUERA ° 0 0 1 Djouna 1 G GMangueïgne HARAZE-MANGUEIGNE Takalaw GBoum-Kebir G LIBYE Tibesti NIGER N N " " 0 0 ' ' Ennedi Ouest 0 0 ° Kia Ndopto ° 0 Male G 0 1 1 Ennedi Est G Haraze Borkou Massidi-Dongo Moyo Kanem Singako Wadi Fira Alako Barh-El-Gazel Batha SOUDAN G LAC IRO Lac Baltoubaye Ouaddaï G R É P U B L I Q U E C E N T R A F R I C A I N E Hadjer-Lamis -

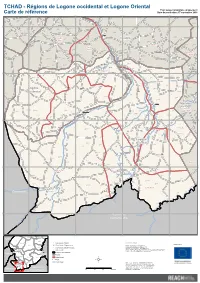

Régions De Logone Occidental Et Logone Oriental

TCHAD - Régions de Logone occidental et Logone Oriental Pour usage humanitaire uniquement Carte de référence Date de production: 07 septembre 2018 15°30'0"E 16°0'0"E 16°30'0"E 17°0'0"E Gounou Koré Marba Kakrao Ambasglao Boudourr Oroungou Gounaye Djouman Goubou Gabrigué Tagal I Drai Mala Djoumane Disou Kom Tombouo Landou Marba Gogor Birem Dikna Goundo Nongom Goumga Zaba I Sadiki Ninga Pari N N " Baktchoro Narégé " 0 0 ' Pian Bordo ' 0 0 3 Bérem Domo Doumba 3 ° ° 9 Brem 9 Tchiré Gogor Toguior Horey Almi Zabba Djéra Kolobaye Kouma Tchindaï Poum Mbassa Kahouina Mogoy Gadigui Lassé Fégué Kidjagué Kabbia Gounougalé Bagaye Bourmaye Dougssigui Gounou Ndolo Aguia Tchilang Kouroumla Kombou Nergué Kolon Laï Batouba Monogoy Darbé Bélé Zamré Dongor Djouni Koubno Bémaye Koli Banga Ngété Tandjile Goun Nanguéré Tandjilé Dimedou Gélgou Bongor Madbo Ouest Nangom Dar Gandil Dogou Dogo Damdou Ngolo Tchapadjigué Semaïndi Layane Béré Delim Kélo Dombala Tchoua Doromo Pont-Carol Dar Manga Beyssoa Manaï I Baguidja Bormane Koussaki Berdé Tandjilé Est Guidari Tandjilé Guessa Birboti Tchagra Moussoum Gabri Ngolo Kabladé Kasélem Centre Koukwala Toki Béro Manga Barmin Marbelem Koumabodan Ter Kokro Mouroum Dono-Manga Dono Manga Nantissa Touloum Kalité Bayam Kaga Palpaye Mandoul Dalé Langué Delbian Oriental Tchagra Belimdi Kariadeboum Dilati Lao Nongara Manga Dongo Bitikim Kangnéra Tchaouen Bédélé Kakerti Kordo Nangasou Bir Madang Kemkono Moni Bébala I Malaré Bologo Bélé Koro Garmaoa Alala Bissigri Dotomadi Karangoye Dadjilé Saar-Gogne Bala Kaye Mossoum Ngambo Mossoum -

SALAMAT TANDJILE CHARI BAGUIRMI GUERA LOGONE ORIENTAL MANDOUL MOYEN CHARI CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC Legend

TCHAD:REGION DU MOYEN-CHARI Juin 2010 E E E E " " " " 0 0 0 0 ' ' ' ' 0 0 0 0 ° ° ° ° 7 8 9 0 1 1 1 2 Seaba BAGUIRMI Chinguil Kiéké Matègn Maïra Al Bidia Chinguil Baranga Zan Ndaba Cisi Madi Balo Djomal Ségué Badi Biéré Am Kiféou Chérif Boubour Bankéri Djouna Djouna Mogo Bao Gouri Djember Gadang-gougouri Barao Tiolé Kadji Barlet Gofena Boumbouri Bilabou Karo Al Fatchotchoy Al Oubana Aya Hour Bala Tieau Djoumboul Timan Méré Banker GUE R A Djogo Goudak Aya I BARH BAHR Lagouay SIGNAKA Djimèz Am Biringuel LOUG CHARI Gamboul Djadja Al Itéin AZOUM Miltou Kourmal Tor CHA R I B A GU I RM I Gangli Komo Djigel Karou Siho Tiguili Boum Dassik Gou Tilé Kagni Kabir Takalaou Bibièn Nougar Bobèch Boum Kabir Baranga Lagoye Moufo Al Frèch Kébir Bir El Tigidji Souka Rhala Kané Damraou Délou Djiour Tari Gour Kofé Bouni Djindi Gouaï Béménon Dogoumbo Sarabara Tim Ataway Bakasao Nargon Damtar N N " Korbol " 0 Bar 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 0 Korbol Malé Dobo Dipkir 0 1 Kalmouna Sali 1 Lour Dik Guer Malbom Sakré Bouane Kouin BAHR KOH Délèb Migna Tousa Dongo Direk Wok Guéléhé SALAMAT Guélé Kalbani Singako Kwaloum Kagnel Tchadjaragué Moula Kouno Gourou Niou Balétoundou Singako Koniène Alako Biobé Kindja Ndam Baltoubay Alako Yemdigué Ndam Kalan Bahitra Baltoubaye Balé Dène Balékolo Balékoutou Niellim Ala Danganjin Kidjokadi Gaogou Mirem Ngina Pongouo Tchigak Moul Boari Kokinio Koubatiembi Roukou TANDJILE EST Palik Bébolo Roro Koubounda Gori Koulima Korakadja Simé Djindjibo Bari Kaguessem Gotobé Balé Dindjebo Gounaye Tolkaba Gilako Béoulou Yanga Ladon Mandjoua Gabrigué Hol Bembé -

Myr 2010 Chad.Pdf

ORGANIZATIONS PARTICIPATING IN CONSOLIDATED APPEAL CHAD ACF CSSI IRD UNDP ACTED EIRENE Islamic Relief Worldwide UNDSS ADRA FAO JRS UNESCO Africare Feed the Children The Johanniter UNFPA AIRSERV FEWSNET LWF/ACT UNHCR APLFT FTP Mercy Corps UNICEF Architectes de l’Urgence GOAL NRC URD ASF GTZ/PRODABO OCHA WFP AVSI Handicap International OHCHR WHO BASE HELP OXFAM World Concern Development Organization CARE HIAS OXFAM Intermon World Concern International CARITAS/SECADEV IMC Première Urgence World Vision International CCO IMMAP Save the Children Observers: CONCERN Worldwide INTERNEWS Sauver les Enfants de la Rue International Committee of COOPI INTERSOS the Red Cross (ICRC) Solidarités CORD IOM Médecins Sans Frontières UNAIDS CRS IRC (MSF) – CH, F, NL, Lux TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................................. 1 Table I: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by cluster) ................................................... 3 Table II: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by appealing organization).......................... 4 Table III: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by priority)................................................... 5 2. CHANGES IN THE CONTEXT, HUMANITARIAN NEEDS AND RESPONSE ........................................... 6 3. PROGRESS TOWARDS ACHIEVING STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES AND SECTORAL TARGETS .......... 9 3.1 STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................................ -

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Chad

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO CHAD Original Map Courtesy of the UN Cartographic Section 15° 20° 25° The boundaries and names used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the U.S. Government. EGYPT CHAD LIBYA TIBESTITIBESTI Aozou Bardaï SUDAN Zouar 20° Séguédine EASTERN CHAD . ASI ? .. .. .. .. .. Bilma . .. FAO . ... BORKOUBORKO. .U ... ENNEDIENNEDI OCHA B UNICEF J . .. .. .. ° . .. .. Faya-Largeau .. .... .... ..... NIGER . .. .. .. .. .. WFP/UNHAS ? .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... ... ... .. .. .... WFP . ... .. WESTERN CHAD ... ... Fada .. ..... .. .... ASI ? . .... ACF . Committee d’Aide Médicale UNICEF J CORD WFP WADI FIRA Koro HIAS j D ICRC Toro CRS C ICRC G UNHCR Iriba 15 IFRC KANEMKANEM Arada WADIWADI FIRAFIRA J BAHRBAHR ELEL OUADDAÏ IMC ° Nokou Guéréda GAZELGAZEL Biltine ACTED Internews Nguigmi J Salal Am Zoer Mao BATHABATHA CRS C IRC JG Abéché Jesuit Refugee Service LACLAC IMC Bol Djédaa Ngouri Moussoro Oum Première Mentor Initiative Ati Hadjer OUADDAOOUADDAÏUADDAÏ Urgence OXFAM GB J Massakory IFRC IJ Refugee Ed. Trust HADJER-LAMISHADJER-LAMIS Am Dam Goz Mangalmé Première Urgence Bokoro Mongo Beïda UNHAS ? Maltam I Camp N'Djamena DARDAR SILASILA WCDO Gamboru-Ngala C UNHCR Maiduguri CHARI-CHARI- Koukou G Kousseri BAGUIRMIBAGUIRMI GUERAGUERA Angarana Massenya Dar Sila NIGERIA Melfi Abou Deïa ACTED Gélengdeng J Am Timan IMC MAYO-MAYO- Bongor KEBBIKEBBI SALAMATSALAMAT MENTOR 10° Fianga ESTEST Harazé WCDO SUDAN 10° Mangueigne C MAYO-MAYO- TANDJILETANDJILE MOYEN-CHARIMOYEN-CHARI -

Ending Extreme Poverty and Sharing Prosperity: Progress and Policies

Ending Extreme Poverty and Sharing Prosperity: Progress and Policies Marcio Cruz, James Foster, Bryce Quillin and Philip Schellekens1 Approved for distribution by Kaushik Basu Chief Economist and Senior Vice President, World Bank Policy Research Notes (PRNs) are prepared under the direction of the World Bank Chief Economist and Senior Vice President for Development Economics. PRNs combine and distill existing and new research to inform discussion on topical policy issues. They are aimed at a broad audience interested in economic policy. DISCLAIMER: Policy Research Notes represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent WBG views or policy. The views expressed herein should be attributed to the authors and not to the WBG, its Board of Executive Directors, or its management. This note reflects data available as of mid-September 2015. Authors’ Email Addresses: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 1 The main authors of this note are: Marcio Cruz (Economist, Development Prospects Group), James Foster (Professor of Economics and International Affairs, George Washington University; Research Associate, Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, Oxford University; World Bank consultant), Bryce Quillin (Senior Economist, Development Prospects Group), and Philip Schellekens (Lead Economist, Development Prospects Group). This note is based on Chapter 1 of the Global Monitoring Report 2015/2016: Development in an Era of Demographic Change and is produced under the guidance of Kaushik Basu, Indermit Gill and Ayhan Kose, with inputs from Carter J. Brandon, Vandana Chandra, Emanuela Galasso, Dean M. Jolliffe, Jin Ho Kim, Eugenia Moran-Suarez, Rinku Murgai, Israel Osorio-Rodarte, Espen B. -

Chad: a New Conflict Resolution Framework

CHAD: A NEW CONFLICT RESOLUTION FRAMEWORK Africa Report N°144 – 24 September 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS.................................................I I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. A CRISIS OF THE STATE ........................................................................................... 2 A. 1990-2000: MISSED OPPORTUNITIES FOR RECONCILIATION......................................................2 B. OIL, CLIENTELISM AND CORRUPTION........................................................................................3 1. Clientelism and generalised corruption ..............................................................................3 2. The oil curse .......................................................................................................................4 C. MILITARISATION OF THE ADMINISTRATION AND POPULATION ..................................................5 D. NATIONAL AND RELIGIOUS DIVIDES .........................................................................................6 III. THE ACTORS IN THE CRISIS................................................................................... 8 A. THE POLITICAL OPPOSITION .....................................................................................................8 1. Repression and co-option ...................................................................................................8 2. The political platform of -

Monthly Food Security Update for Chad: March 22, 2002

Monthly Food Security Update for Chad: March 22, 2002 A joint report by FEWS NET and the National Nutritional Center for Nutrition and Food Technology (CNNTA) Summary In the context of food security monitoring, FEWS NET and the National Center for Nutrition and Food Technology (CNNTA) organized a small-scale anthropometric survey from February 27 through March 12 in the eastern Sahelian zone, visiting Rural Biltine, Arada, Kalait, Iriba, Guereda, Tiné and Bahai sub-prefectures. Preliminary results indicated that the rate of global acute malnutrition, calculated as a percent of the median, was less than 5 percent in about half of the survey villages (results from other villages are still expected). On the basis of these results, the overall food situation is considered good in the survey areas. Cereal availability and accessibility are good in most departments of the country. However, accessibility remains difficult for households in Borkou, Ennedi and Tibesti Departments (known as BET) in the far northern part of the country that do not produce cereals. These departments get their food supplies from neighboring Biltine and Ouaddai Departments. Nonetheless, transportation to and from the BET is difficult due to the rugged condition of desert roads. Current off-season farming activities include tending market gardens and harvesting produce, and harvesting berbéré (off-season, flood-irrigated sorghum) in the berbéré producing zones of Mayo Boneye, Mayo Dalla, Dar Sila and Salamat Departments where the crop harvests are reasonably good. Irrigated wheat in the modern sector polders of Lake Chad is nearing maturity while some wheat is already being harvested in the traditional polders. -

Chapter 1 Present Situation of Chad's Water Development and Management

1 CONTEXT AND DEMOGRAPHY 2 With 7.8 million inhabitants in 2002, spread over an area of 1 284 000 km , Chad is the 25th largest 1 ECOSI survey, 95-96. country in Africa in terms of population and the 5th in terms of total surface area. Chad is one of “Human poverty index”: the poorest countries in the world, with a GNP/inh/year of USD 2200 and 54% of the population proportion of households 1 that cannot financially living below the world poverty threshold . Chad was ranked 155th out of 162 countries in 2001 meet their own needs in according to the UNDP human development index. terms of essential food and other commodities. The mean life expectancy at birth is 45.2 years. For 1000 live births, the infant mortality rate is 118 This is in fact rather a and that for children under 5, 198. In spite of a difficult situation, the trend in these three health “monetary poverty index” as in reality basic indicators appears to have been improving slightly over the past 30 years (in 1970-1975, they were hydraulic infrastructure respectively 39 years, 149/1000 and 252/1000)2. for drinking water (an unquestionably essential In contrast, with an annual population growth rate of nearly 2.5% and insufficient growth in agricultural requirement) is still production, the trend in terms of nutrition (both quantitatively and qualitatively) has been a constant insufficient for 77% of concern. It was believed that 38% of the population suffered from malnutrition in 1996. Only 13 the population of Chad.