June 1988 Vulnerability Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tcd Str Hno2017 Fr 20161216.Pdf

APERÇU DES 2017 BESOINS HUMANITAIRES PERSONNES DANS LE BESOIN 4,7M NOV 2016 TCHAD OCHA/Naomi Frerotte Ce document est élaboré au nom de l'Equipe Humanitaire Pays et de ses partenaires. Ce document présente la vision des crises partagée par l'Equipe Humanitaire Pays, y compris les besoins humanitaires les plus pressants et le nombre estimé de personnes ayant besoin d'assistance. Il constitue une base factuelle consolidée et contribue à informer la planification stratégique conjointe de réponse. Les appellations employées dans le rapport et la présentation des différents supports n'impliquent pas d'opinion quelconque de la part du Secrétariat de l'Organisation des Nations Unies concernant le statut juridique des pays, territoires, villes ou zones, ou de leurs autorités, ni de la délimitation de ses frontières ou limites géographiques. www.unocha.org/tchad www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/chad @OCHAChad PARTIE I : PARTIE I : RÉSUMÉ Besoins humanitaires et chiffres clés Impact de la crise Personnes dans le besoin Sévérité des besoins 03 PERSONNESPARTIE DANS LEI : BESOIN Personnes dans le besoin par Sites et Camps de déplacement catégorie (en milliers) M Site de retournés 4,7 Population Camp de réfugiés Ressortissants locale de pays tiers Sites/lieux de déplacement interne EGYPTE Personnes xx déplacées Réfugiés MAS supérieur à 2% internes Retournés Phases du Cadre Harmonisé (période projetée, juin-août 2017) LIBYE Minimale (phase 1) Sous pression (phase 2) Crise (phase 3) TIBESTI 13 NIGER ENNEDI OUEST 35 ENNEDI EST BORKOU 82 04 -

Paper Submitted for Presentation at UNU-WIDER’S Conference, Held in Maputo on 5-6 July 2017

DRAFT WIDER Development Conference Public economics for development 5-6 July 2017 | Maputo, Mozambique This is a draft version of a conference paper submitted for presentation at UNU-WIDER’s conference, held in Maputo on 5-6 July 2017. This is not a formal publication of UNU-WIDER and may refl ect work-in-progress. THIS DRAFT IS NOT TO BE CITED, QUOTED OR ATTRIBUTED WITHOUT PERMISSION FROM AUTHOR(S). The impact of oil exploitation on wellbeing in Chad Abstract This study assesses the impact of oil revenues on wellbeing in Chad. Data used come from the two last Chad Household Consumption and Informal Sector Surveys ECOSIT 2 & 3 conducted in 2003 and 2011 by the National Institute of Statistics and Demographic Studies. A synthetic index of multidimensional wellbeing (MDW) is first estimated using a multiple components analysis based on a large set of welfare indicators. The Difference-in-Difference approach is then employed to assess the impact of oil revenues on the average MDW at departmental level. Results show that departments receiving intense oil transfers increased their MDW about 35% more than those disadvantaged by the oil revenues redistribution policy. Also, the farther a department is from the capital city N’Djamena, the lower its average MDW. Economic inclusion may be better promoted in Chad if oil revenues fit local development needs and are effectively directed to the poorest departments. Keys words: Poverty, Multidimensional wellbeing, Oil exploitation, Chad, Redistribution policy. JEL Codes: I32, D63, O13, O15 Authors Gadom -

TCHAD Province Du Salamat Octobre 2019

TCHAD Province du Salamat Octobre 2019 18°30'0"E 19°0'0"E 19°30'0"E 20°0'0"E 20°30'0"E 21°0'0"E 21°30'0"E 22°0'0"E Dadouar G GAm Bourougne Bang-Bang G Bagoua GKofilo G Dogdore GZarli G Golonti ABTOUYOUR G N Mogororo N " " 0 Koukou G 0 ' G Koukou-Angarana ' 0 G G 0 ° ABTOUYOUR Koukou angara ° 2 G 2 1 Niergui Badago G Goz Amir Tioro 1 G Louboutigue G GAbgué GUÉRA GTounkoul MANGALMÉ KerfGi MANGALMÉ Kerfi GUÉRA GIdbo GBandikao GAl Ardel Localités GFoulounga GMouraye Capitale N ABOUDÉIA N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 Chef-Lieu de province 3 3 ° ° 1 1 1 1 Chef-Lieu de département G Aboudéïa GAm-Habilé GAgrab Dourdoura G Chef-Lieu de sous-préfecture GArdo Camp de réfugiés GDarasna Daradir G Site de déplacés/retournés GMirer Village hôte GZarzoura Amdjabir G Infrastructures GLiwi G Centre de santé/Hopital GIdater Aérodrome Piste d'atterrissage Am Karouma G Am-Timan G Route principale N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 G Am Senene 0 ° Goz Djerat ° 1 G 1 Route secondaire 1 1 Piste Zakouma Limites administratives Aoukalé Frontière nationale S A L A M A T Limite de province Limite de département BARH-SIGNAKA Hydrographie GDaguela BARH-SIGNAKA Plan d'eau BAHR-AZOUM Département Chinguil G GKieke N Zane N " G " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 3 3 ° GUERA ° 0 0 1 Djouna 1 G GMangueïgne HARAZE-MANGUEIGNE Takalaw GBoum-Kebir G LIBYE Tibesti NIGER N N " " 0 0 ' ' Ennedi Ouest 0 0 ° Kia Ndopto ° 0 Male G 0 1 1 Ennedi Est G Haraze Borkou Massidi-Dongo Moyo Kanem Singako Wadi Fira Alako Barh-El-Gazel Batha SOUDAN G LAC IRO Lac Baltoubaye Ouaddaï G R É P U B L I Q U E C E N T R A F R I C A I N E Hadjer-Lamis -

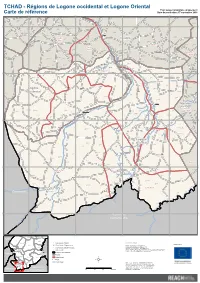

Régions De Logone Occidental Et Logone Oriental

TCHAD - Régions de Logone occidental et Logone Oriental Pour usage humanitaire uniquement Carte de référence Date de production: 07 septembre 2018 15°30'0"E 16°0'0"E 16°30'0"E 17°0'0"E Gounou Koré Marba Kakrao Ambasglao Boudourr Oroungou Gounaye Djouman Goubou Gabrigué Tagal I Drai Mala Djoumane Disou Kom Tombouo Landou Marba Gogor Birem Dikna Goundo Nongom Goumga Zaba I Sadiki Ninga Pari N N " Baktchoro Narégé " 0 0 ' Pian Bordo ' 0 0 3 Bérem Domo Doumba 3 ° ° 9 Brem 9 Tchiré Gogor Toguior Horey Almi Zabba Djéra Kolobaye Kouma Tchindaï Poum Mbassa Kahouina Mogoy Gadigui Lassé Fégué Kidjagué Kabbia Gounougalé Bagaye Bourmaye Dougssigui Gounou Ndolo Aguia Tchilang Kouroumla Kombou Nergué Kolon Laï Batouba Monogoy Darbé Bélé Zamré Dongor Djouni Koubno Bémaye Koli Banga Ngété Tandjile Goun Nanguéré Tandjilé Dimedou Gélgou Bongor Madbo Ouest Nangom Dar Gandil Dogou Dogo Damdou Ngolo Tchapadjigué Semaïndi Layane Béré Delim Kélo Dombala Tchoua Doromo Pont-Carol Dar Manga Beyssoa Manaï I Baguidja Bormane Koussaki Berdé Tandjilé Est Guidari Tandjilé Guessa Birboti Tchagra Moussoum Gabri Ngolo Kabladé Kasélem Centre Koukwala Toki Béro Manga Barmin Marbelem Koumabodan Ter Kokro Mouroum Dono-Manga Dono Manga Nantissa Touloum Kalité Bayam Kaga Palpaye Mandoul Dalé Langué Delbian Oriental Tchagra Belimdi Kariadeboum Dilati Lao Nongara Manga Dongo Bitikim Kangnéra Tchaouen Bédélé Kakerti Kordo Nangasou Bir Madang Kemkono Moni Bébala I Malaré Bologo Bélé Koro Garmaoa Alala Bissigri Dotomadi Karangoye Dadjilé Saar-Gogne Bala Kaye Mossoum Ngambo Mossoum -

SALAMAT TANDJILE CHARI BAGUIRMI GUERA LOGONE ORIENTAL MANDOUL MOYEN CHARI CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC Legend

TCHAD:REGION DU MOYEN-CHARI Juin 2010 E E E E " " " " 0 0 0 0 ' ' ' ' 0 0 0 0 ° ° ° ° 7 8 9 0 1 1 1 2 Seaba BAGUIRMI Chinguil Kiéké Matègn Maïra Al Bidia Chinguil Baranga Zan Ndaba Cisi Madi Balo Djomal Ségué Badi Biéré Am Kiféou Chérif Boubour Bankéri Djouna Djouna Mogo Bao Gouri Djember Gadang-gougouri Barao Tiolé Kadji Barlet Gofena Boumbouri Bilabou Karo Al Fatchotchoy Al Oubana Aya Hour Bala Tieau Djoumboul Timan Méré Banker GUE R A Djogo Goudak Aya I BARH BAHR Lagouay SIGNAKA Djimèz Am Biringuel LOUG CHARI Gamboul Djadja Al Itéin AZOUM Miltou Kourmal Tor CHA R I B A GU I RM I Gangli Komo Djigel Karou Siho Tiguili Boum Dassik Gou Tilé Kagni Kabir Takalaou Bibièn Nougar Bobèch Boum Kabir Baranga Lagoye Moufo Al Frèch Kébir Bir El Tigidji Souka Rhala Kané Damraou Délou Djiour Tari Gour Kofé Bouni Djindi Gouaï Béménon Dogoumbo Sarabara Tim Ataway Bakasao Nargon Damtar N N " Korbol " 0 Bar 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 0 Korbol Malé Dobo Dipkir 0 1 Kalmouna Sali 1 Lour Dik Guer Malbom Sakré Bouane Kouin BAHR KOH Délèb Migna Tousa Dongo Direk Wok Guéléhé SALAMAT Guélé Kalbani Singako Kwaloum Kagnel Tchadjaragué Moula Kouno Gourou Niou Balétoundou Singako Koniène Alako Biobé Kindja Ndam Baltoubay Alako Yemdigué Ndam Kalan Bahitra Baltoubaye Balé Dène Balékolo Balékoutou Niellim Ala Danganjin Kidjokadi Gaogou Mirem Ngina Pongouo Tchigak Moul Boari Kokinio Koubatiembi Roukou TANDJILE EST Palik Bébolo Roro Koubounda Gori Koulima Korakadja Simé Djindjibo Bari Kaguessem Gotobé Balé Dindjebo Gounaye Tolkaba Gilako Béoulou Yanga Ladon Mandjoua Gabrigué Hol Bembé -

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Chad

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO CHAD Original Map Courtesy of the UN Cartographic Section 15° 20° 25° The boundaries and names used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the U.S. Government. EGYPT CHAD LIBYA TIBESTITIBESTI Aozou Bardaï SUDAN Zouar 20° Séguédine EASTERN CHAD . ASI ? .. .. .. .. .. Bilma . .. FAO . ... BORKOUBORKO. .U ... ENNEDIENNEDI OCHA B UNICEF J . .. .. .. ° . .. .. Faya-Largeau .. .... .... ..... NIGER . .. .. .. .. .. WFP/UNHAS ? .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... ... ... .. .. .... WFP . ... .. WESTERN CHAD ... ... Fada .. ..... .. .... ASI ? . .... ACF . Committee d’Aide Médicale UNICEF J CORD WFP WADI FIRA Koro HIAS j D ICRC Toro CRS C ICRC G UNHCR Iriba 15 IFRC KANEMKANEM Arada WADIWADI FIRAFIRA J BAHRBAHR ELEL OUADDAÏ IMC ° Nokou Guéréda GAZELGAZEL Biltine ACTED Internews Nguigmi J Salal Am Zoer Mao BATHABATHA CRS C IRC JG Abéché Jesuit Refugee Service LACLAC IMC Bol Djédaa Ngouri Moussoro Oum Première Mentor Initiative Ati Hadjer OUADDAOOUADDAÏUADDAÏ Urgence OXFAM GB J Massakory IFRC IJ Refugee Ed. Trust HADJER-LAMISHADJER-LAMIS Am Dam Goz Mangalmé Première Urgence Bokoro Mongo Beïda UNHAS ? Maltam I Camp N'Djamena DARDAR SILASILA WCDO Gamboru-Ngala C UNHCR Maiduguri CHARI-CHARI- Koukou G Kousseri BAGUIRMIBAGUIRMI GUERAGUERA Angarana Massenya Dar Sila NIGERIA Melfi Abou Deïa ACTED Gélengdeng J Am Timan IMC MAYO-MAYO- Bongor KEBBIKEBBI SALAMATSALAMAT MENTOR 10° Fianga ESTEST Harazé WCDO SUDAN 10° Mangueigne C MAYO-MAYO- TANDJILETANDJILE MOYEN-CHARIMOYEN-CHARI -

Assistance Pour Un Mois

Impact COVID-19 2ème niveau Population Total population 3ème niveau administratif Population totale en Assistance pour un mois administratif totale en Phase en insécurité Phase 2 3 à 5 grand centre alimentaire Céréales huile (bidon sucre Niébé rural urbains (tonne) de 20 litre) (tonne) (tonne) Batha Batha Est 58 380 18 575 7 805 26 380 11 676 7 805 220 4 397 110 44 Batha Batha Ouest 87 276 61 093 11 668 72 761 17 455 11 668 606 12 127 303 121 Batha Fitri 40 613 9 747 5 430 15 177 8 123 5 430 126 2 529 63 25 Barh El Gazal Bahr El Gazal Nord 29 142 24 589 3 896 28 485 5 828 3 896 237 4 747 119 47 Barh El Gazal Bahr El Gazal Ouest 27 847 19 891 3 723 23 614 5 569 3 723 197 3 936 98 39 Barh El Gazal Bahr El Gazal Sud 74 851 60 297 10 007 70 304 14 970 10 007 586 11 717 293 117 Borkou Borkou Yala 9 275 8 533 1 240 9 773 1 855 1 240 81 1 629 41 16 Borkou Borkou 45 271 28 169 6 052 34 221 9 054 6 052 285 5 703 143 57 Chari-Baguirmi Baguirmi 49 375 0 6 601 6 601 9 875 6 601 55 1 100 28 11 Chari-Baguirmi Chari 24 222 0 3 238 3 238 4 844 3 238 27 540 13 5 Chari-Baguirmi Loug-Chari 32 807 0 4 386 4 386 6 561 4 386 37 731 18 7 Guera Guera 50 749 30 449 6 785 37 234 10 150 6 785 310 6 206 155 62 Guera Abtouyour 64 050 41 879 8 563 50 442 12 810 8 563 420 8 407 210 84 Guera Mangalmé 25 137 13 965 3 361 17 326 5 027 3 361 144 2 888 72 29 Guera Barh Signaka 30 480 15 240 4 075 19 315 6 096 4 075 161 3 219 80 32 Hajer Lamis Dababa 63 866 20 168 8 538 28 706 12 773 8 538 239 4 784 120 48 Hajer Lamis Dagana 60 971 16 629 8 151 24 780 12 194 8 151 206 4 -

Chad: a New Conflict Resolution Framework

CHAD: A NEW CONFLICT RESOLUTION FRAMEWORK Africa Report N°144 – 24 September 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS.................................................I I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. A CRISIS OF THE STATE ........................................................................................... 2 A. 1990-2000: MISSED OPPORTUNITIES FOR RECONCILIATION......................................................2 B. OIL, CLIENTELISM AND CORRUPTION........................................................................................3 1. Clientelism and generalised corruption ..............................................................................3 2. The oil curse .......................................................................................................................4 C. MILITARISATION OF THE ADMINISTRATION AND POPULATION ..................................................5 D. NATIONAL AND RELIGIOUS DIVIDES .........................................................................................6 III. THE ACTORS IN THE CRISIS................................................................................... 8 A. THE POLITICAL OPPOSITION .....................................................................................................8 1. Repression and co-option ...................................................................................................8 2. The political platform of -

République Du Tchad

Enquête Nationale Post-récoltes sur la Sécurité Alimentaire des Ménages Ruraux du Tchad République du Tchad Février 2012 Données de novembre/décembre 2011 Enquête Nationale post-récoltes sur la Sécurité Alimentaire des ménages ruraux du Tchad Pour plus d’informations, contacter : Bureau de pays du PAM Tchad Unité VAM/M&E, Section Programme : [email protected] Anne-Claire Mouilliez, Bureau du PAM Tchad: [email protected] Wilfred Nkwambi, Bureau du PAM Tchad: [email protected] © Programme Alimentaire Mondial, Service de l’Analyse de la Sécurité Alimentaire (VAM), février 2012 Programme alimentaire mondial des Nations Unies (PAM) Siège social : Via C.G. Viola 68, Parco de Medici, 00148, Rome, Italie Toutes les informations sur le service de l’Analyse de la Sécurité Alimentaire (VAM) et les rapports en format électronique sur http://www.wfp.org/food-security ou [email protected] 2 Table des matières LISTE DES TABLEAUX ................................................................................................................................................ 6 LISTE DES FIGURES .................................................................................................................................................... 6 LISTE DES CARTES ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 LISTE DES ANNEXES .................................................................................................................................................. -

Chapter 1 Present Situation of Chad's Water Development and Management

1 CONTEXT AND DEMOGRAPHY 2 With 7.8 million inhabitants in 2002, spread over an area of 1 284 000 km , Chad is the 25th largest 1 ECOSI survey, 95-96. country in Africa in terms of population and the 5th in terms of total surface area. Chad is one of “Human poverty index”: the poorest countries in the world, with a GNP/inh/year of USD 2200 and 54% of the population proportion of households 1 that cannot financially living below the world poverty threshold . Chad was ranked 155th out of 162 countries in 2001 meet their own needs in according to the UNDP human development index. terms of essential food and other commodities. The mean life expectancy at birth is 45.2 years. For 1000 live births, the infant mortality rate is 118 This is in fact rather a and that for children under 5, 198. In spite of a difficult situation, the trend in these three health “monetary poverty index” as in reality basic indicators appears to have been improving slightly over the past 30 years (in 1970-1975, they were hydraulic infrastructure respectively 39 years, 149/1000 and 252/1000)2. for drinking water (an unquestionably essential In contrast, with an annual population growth rate of nearly 2.5% and insufficient growth in agricultural requirement) is still production, the trend in terms of nutrition (both quantitatively and qualitatively) has been a constant insufficient for 77% of concern. It was believed that 38% of the population suffered from malnutrition in 1996. Only 13 the population of Chad. -

Province Du Ouaddai Octobre 2019

TCHAD Province du Ouaddai Octobre 2019 20°0'0"E 20°30'0"E 21°0'0"E 21°30'0"E 22°0'0"E G G Dicker Kineda Kolonga G GFarey Angara G GGorane G Malanga Koïbo G G Kassiné W A D I F I R A GMiti Miti GKour Kouré GDouguine Abtoboye Erné G Am-Zoer G Guérry GAmhitane GTerkeme G Bourtail Mata Baibor G Localités Capitale Chef-Lieu de province GDjimeze N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 Chef-Lieu de département ° ° 4 Krey 4 1 G 1 Doulbarid Chef-Lieu de sous-préfecture G GH. Doukour GKoudouguine Magare Camp de réfugiés Mabrone G Site de déplacés/retournés Village hôte Kawa G Infrastructures G GTaïba G Kamina Centre de santé/Hopital AEB G GG G G Djatinié G Aérodrome Salamat Abéché Barout GMoura G Tourané GTraoné Piste d'atterrissage Gaga Amleyouna G G Route principale Mabrouka G Fochi G Route secondaire GHadjilidje Erlé MG olou Piste Limites administratives G Abougoudam Frontière nationale Abougoulegne Djazire Tama G Limite de province G GDop-Dop Farchana G Limite de département GKidjimira Hilouta G GMarchout Hydrographie Plan d'eau N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 Abhkouta 0 3 G 3 ° ° 3 BATHA EST 3 1 1 G Bredjing GAdré GTongori Adre G Treguine GHadjer-Hadid G Hadjer-Hadid DjoroGko MahamataG Rimele G O U A D D A I G Chokoyan B A T H A MG arfa LIBYE GAndokone Tibesti Mourdiguine GAssartni G NIGER Abkar-Djombo GHougoune GArkoum Goungour Ennedi Ouest G Abkar G GKatafa Ennedi Est Borkou Goundiang G S O U D A N Kouchkouchné G Kanem Wadi Fira GAllacha GAtarak Barh-El-Gazel Batha SOUDAN Hileket Lac GMargachagane G Ouaddaï Hadjer-Lamis GAmdeguigue N'Djaména Sila NIGÉRIA N N " " Chari-Baguirmi -

Tchad: Situations De Conflits, Inondations Et Ennemis Des Cultures Mise À Jour Du 9 Octobre 2017

Tchad: situations de conflits, inondations et ennemis des cultures Mise à jour du 9 octobre 2017 Légendes Tibesti Ouest TIBESTI Inondations Tibesti Est Conflits éleveurs Oiseaux granivores Chenilles légionnaires Fada ENNEDI OUEST Am-Djarass Borkou Yala ENNEDI EST 7 oct. à Koundjourou BORKOU (Dpt de Batha Ouest) Destruction des Borkou cultures par les Mourtcha oiseaux granivores à 14.000 ha envahies, Wadi Hawar 6.241,8 t détruites et Nord Kanem Kobé 4.964 ménages KANEM WADI FIRA Mégri touchés Biltine Barh-El-Gazel Nord 7 oct. Dar-Tama Batha Ouest à Ouaddi Faman Kanem BARH-EL-GAZEL Fouli (18.108 habitants) BATHA Batha Est Barh-El-Gazel Sud Ouara Assoungha dans la sous- Kaya LAC Wadi Bissam OUADDAÏ Wayi Barh-El-Gazel Ouest préfecture d’Arada Mamdi (Dpt de Biltine). Dagana Abdi Fitri Conflits ente HADJER-LAMIS Mangalmé Haraze-Al-Biar éleveurs 4 oct. N’Djamena Dababa Djourf Al Ahmar N'Djaména Guéra SILA 3 morts. Invasion de champ Abtouyour dans la banlieue de N'DJAMENA Kimiti Chari Baguirmi et du champ de GUÉRA Aboudéia maïs de l’ITRAD par CHARI-BAGUIRMI Inondations: Bahr-Azoum les chenilles Mayo-Lemié Barh-Signaka Salamat: Barh Azoum: env. 388,5 ha SALAMAT légionnaires détruites Loug-Chari Mayo-Boneye Mandoul: Mandoul Oriental: 42 villages, MAYO-KEBBI EST 1.445 personnes touchées, 1.453 ha. Pas Mayo-Binder Mont Illi Haraze-Mangueigne de données sur le Mandoul Oriental et Lac Léré Lac Iro Kabbia Tandjilé Est Bahr-Köh Barh Sara affectés aussi MAYO-KEBBI OUEST Tandjile OuestTANDJILÉ MOYEN-CHARI Tandjilé Centre Logone Oriental: Dpt de Nya Pende: Mayo-Dallah Mandoul Oriental Guéni Ngourkosso La Pendé 465 ha détruites – pas de ménages Lac Wey Dodjé MANDOUL touchés estimés La NyaMandoul Occidental LOGONE OCCIDENTAL Grande Sido Kouh Est Nya, Kouh-Est, Pende: pas de données LOGONE ORIENTAL Barh-Sara Kouh Ouest sur les personnes et superficies Monts de Lam La Nya Pendé Affectées Moyen Chari: Grande Sido: env.