Political Manipulation at Home, Military Intervention Abroad, Challenging Times Ahead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darfuri Refugees Both in Chad and Kenya, Competition Over Scarce Natural Has Drawn International Attention

© 2011 Center for Applied Linguistics The contents of this publication were developed under an agreement nanced by the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, United States Department of State, but do not necessarily represent the policy of that agency and should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. The U.S. Department of State reserves a royalty-free, nonexclusive, and irrevocable right to reproduce, publish, or otherwise use, and to authorize others to use, this work for Government purposes. The Darfuri The region, historically separate and long neglected by the violence, and abduction are regular occurrences. In addition, government in Khartoum, lacks basic infrastructure and social competition over scarce natural resources in the semi-arid services. In 2003, non-Arab rebel groups, of which the Justice desert environment of the east has created tensions between and Equality Movement (JEM) is the best known, launched the host community and the refugee populations. Both Chad an uprising against the Sudanese government, accusing the and Sudan have experienced severe desertification, causing government of favoring Arabs over the non-Arab ethnic groups. tensions over water, especially in places with large concentra- Since then, the Darfuri civilians of non-Arab descent have tions of people, such as refugee camps. come under attack from government troops, nomadic militia, and rebel groups. Entire villages have been burned down, wells Located in Northwestern Kenya, Kakuma Refugee Camp is poisoned, and people raped, tortured, and killed. In December host to more than 70,000 refugees. Physical conditions in the 2003, some 2,300 Darfuri villages were destroyed by the Janja- semi-arid desert environment of Kakuma are harsh. -

Ugamunc Xxiii Au

UGAMUNC XXIII AU 1 UGAMUNC XXIII AU Image from: http://bamendaonline.net/blog/au-summit-approves-creation-of-african-monetary-fund/ 2 UGAMUNC XXIII AU Dear Delegates, Welcome to UGAMUNC XXIII and the Committee on the African Union. I am Matthew Gannon, and I will be your Chairman. I am a first-year student at UGA and originally from Valdosta, Georgia. I am pursuing a degree in Finance. This is my first year on the Model United Nations team, and first year chairing a committee. I am also President of the Mell-Lipscomb Community Council. My co-chair, Romello Robinson, is currently a 1st year student at the University of Georgia. He is a dual-major student majoring in history and political science, with a minor in philosophy. He is on the pre-law track here at UGA, and aspires to become a criminal/defense attorney. This is his first year ever doing Model United Nations. Other clubs that he is affiliated with is the Black Male Leadership Society and Georgia Dazes, as well as part of the freshmen council for the United Black Student Legal Association. Outside of university interest, he enjoys to work out at the student fitness center. While the topics discussed will not be sensitive or highly controversial, you are expected to conduct yourselves in a mature and professional manner. Do your best to represent your countries, but also understand that there is a line between role-play and prejudice. Sexism, racism, or any other breaches of decorum outside of the bounds of role-play will not be tolerated. -

Report of the Joint Human Rights Promotion Mission To

AFRICAN UNION UNION AFRICAINE UNIÃO AFRICANA Commission Africaine des Droits de l’Homme & des African Commission on Human & Peoples’ Peuples Rights No. 31 Bijilo Annex Lay-out, Kombo North District, Western Region, P. O. Box 673, Banjul, The Gambia Tel: (220) 441 05 05 /441 05 06, Fax: (220) 441 05 04 E-mail: [email protected]; Web www.achpr.org REPORT OF THE JOINT HUMAN RIGHTS PROMOTION MISSION TO THE REPUBLIC OF CHAD 11 - 19 MARCH 2013 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (the Commission) is grateful to the Government of the Republic of Chad for kindly hosting, from 11 to 19 March 2013, a joint human rights promotion mission undertaken by a delegation of the Commission. The Commission expresses its sincere gratitude to the country’s highest authorities for providing the delegation with the necessary facilities and personnel for the smooth conduct of the mission. The Commission expresses its appreciation to Ms Amina Kodjiyana, Minister for Human Rights and the Promotion of Fundamental Freedoms, and her advisers for their key role in organising the various meetings and for ensuring the success of the mission. 2 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS AfDB : African Development Bank APRM : African Peer Review Mechanism AU : African Union BEPC : Secondary School Leaving Certificate CENI : Independent National Electoral Commission CNARR : National Commission for the Reception and Reintegration of Refugees and Returnees COBAC : Central African Banking Commission CSO : Civil Society Organisation DSG : Deputy Secretary-General -

Chad Poverty Assessment: Constraints to Rural Development

Report No. 16567-CD Chad Poverty Assessment: Constraints to Rural Public Disclosure Authorized Development October 21, 1997 Human Development, Group IV Atrica Region Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Documentof the World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AMTT Agricultural Marketing and Technology Transfer Project AV Association Villageoise BCA Bceufs de culture attelde BEAC Banque des Etats de l'Afrique Centrale BET Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti BIEP Bureau Interminist6rieI d'Etudes et des Projets BNF Bureau National de Frdt CAER Compte Autonome d'Entretien Routier CAR Central African Republic CFA Communautd Financiere Africaine CILSS Comite Inter-etats de Lutte Contre la Sdcheresse au Sahel DCPA Direction de la Commercialisation des Produits Agricoles DD Droit de Douane DPPASA Direction de la Promotion des Produits Agricoles et de la Sdcur DSA Direction de la Statistique Agricole EU European Union FAO Food and Agriculture Organization FEWS Famine Early Warning System FIR Fonds d'Investissement Rural GDP Gross Domestic Product GNP Gross National Product INSAH Institut du Sahel IRCT Institut de Recherche sur le Coton et le Textile LVO Lettre de Voiture Obligatoire MTPT Ministare des Travaux Publics et des Transports NGO Nongovernmental Organization ONDR Office National de Developpement Rural PASET Projet d'Ajustement Sectoriel des Transports PRISAS Programme Regional de Renforcement Institationnel en matie sur la Sdcuritd Alimentaire au Sahel PST Projet Sectoriel Transport RCA Republique Centrafrcaine -

Cross-Cutting Report on Children and Armed Conflict

2010 NO.1 2 June 2010 SECURITY COUNCIL REPORT This report is available online and can be viewed together with Monthly Forecast Reports and Update Reports at cross-cutting REPORT www.securitycouncilreport.org Children and Armed Conflict For over ten years the impact of war on children has been a significant thematic focus for the Security Council. There is now much greater awareness of the issue and some evidence that the inclusion of child protection principles in Council decisions in specific cases is having some impact. However, the Council still encounters some resistance from some governments. And the difficulty of applying effective pressure on non-state actors who recruit child soldiers is a continuing challenge. This is our third Cross-Cutting Report on Children and Armed Conflict. It builds on two previous reports released in 2008 and 2009 which developed a groundbreaking methodology for reviewing, in a cross-cutting format, the effectiveness of Council thematic decisions on children and armed conflict decisions in individual country-specific situations. Our 2010 report details key trends over the past year and provides options for continued Council involvement. Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary examines the details of resolution 1882 1. Executive Summary and and Conclusions and the political process that led to its Conclusions .............................. 2 adoption. However, we have not tried to 2. Background and Normative This is Security Council Report’s third include resolution 1882 in our analysis of Framework ................................ 3 Cross-Cutting Report on Children the Council’s results in incorporating its 3. Key Developments at the and Armed Conflict. The first report in thematic decisions in country-specific Thematic Level ......................... -

Sorghum and Millet Collaborative INTSORMIL Scientific Publications Research Support Program (INTSORMIL CRSP)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln International Sorghum and Millet Collaborative INTSORMIL Scientific Publications Research Support Program (INTSORMIL CRSP) 2010 Sorghum: An Ancient, Healthy and Nutritious Old World Cereal United Sorghum Checkoff Program John Lindsay INTSORMIL Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/intsormilpubs Part of the Agronomy and Crop Sciences Commons, and the Dietetics and Clinical Nutrition Commons United Sorghum Checkoff Program and Lindsay, John, "Sorghum: An Ancient, Healthy and Nutritious Old World Cereal" (2010). INTSORMIL Scientific Publications. 7. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/intsormilpubs/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the International Sorghum and Millet Collaborative Research Support Program (INTSORMIL CRSP) at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in INTSORMIL Scientific Publications yb an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SORGHUM An Ancient, Healthy and Nutritious Old World Cereal 2010 Sorghum: An Ancient, Healthy and Nutritious Old World Cereal Table of Contents Introduction.....................................................................................................................3 Nutritional Contributions of Sorghum....................................................................4 Nutrient Values for Sorghum..........................................................................4 Micronutrients: -

Informal Interactive Dialogues and Other Informal Meetings of the Security Council (As of 13 December 2019)

Informal Interactive Dialogues and Other Informal Meetings of the Security Council (as of 13 December 2019) DATE/ VENUE DESCRIPTIVE SUBJECT BRIEFERS NON‐SC / LISTED IN: NAME NON‐UN PARTICIPANTS JOURNAL SC ANNUAL POW REPORT 27 November 2019 Informal Peace consolidation in Abdoulaye Bathily, former head of the UN Regional Office for Central None NO NO N/A Conf. Rm. 7 interactive West Africa/UNOWAS Africa (UNOCA) and the author of the independent strategic review of dialogue the UN Office for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS); Bintou Keita (Assistant Secretary‐General for Africa); Guillermo Fernández de Soto Valderrama (Permanent Representative of Colombia and Peace Building Commission Chair) 28 August 2019 Informal The situation in Burundi Michael Kingsley‐Nyinah (Director for Central and Southern Africa United Republic of NO NO N/A Conf. Rm. 6 interactive Division, DPPA/DPO), Jürg Lauber (Switzerland PR as Chair of PBC Tanzania dialogue Burundi configuration) 31 July 2019 Informal Peace and security in Amira Elfadil Mohammed Elfadil (AU Comissioner for Social Affairs), Democratic Republic NO NO N/A Conf. Room 7 interactive Africa (Ebola outbreak in David Gressly (Ebola Emergency Response Coordinator), Mark Lowcock of the Congo dialogue the DRC) (Under‐Secretary‐General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator), Michael Ryan (WHO Health Emergencies Programme Executive Director) 7 June 2019 Informal The situation in Libya Mr. Pedro Serrano, Deputy Secretary General of the European External none NO NO N/A Conf. Rm. 7 interactive (Resolution 2292 (2016) Action Service dialogue implementation) 21 March 2019 Informal The situation in the Joost R. Hiltermann (Program Director for Middle East & North Africa, NO NO N/A Conf. -

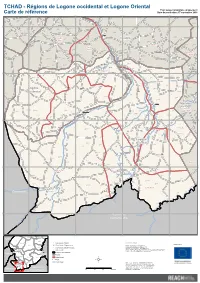

Régions De Logone Occidental Et Logone Oriental

TCHAD - Régions de Logone occidental et Logone Oriental Pour usage humanitaire uniquement Carte de référence Date de production: 07 septembre 2018 15°30'0"E 16°0'0"E 16°30'0"E 17°0'0"E Gounou Koré Marba Kakrao Ambasglao Boudourr Oroungou Gounaye Djouman Goubou Gabrigué Tagal I Drai Mala Djoumane Disou Kom Tombouo Landou Marba Gogor Birem Dikna Goundo Nongom Goumga Zaba I Sadiki Ninga Pari N N " Baktchoro Narégé " 0 0 ' Pian Bordo ' 0 0 3 Bérem Domo Doumba 3 ° ° 9 Brem 9 Tchiré Gogor Toguior Horey Almi Zabba Djéra Kolobaye Kouma Tchindaï Poum Mbassa Kahouina Mogoy Gadigui Lassé Fégué Kidjagué Kabbia Gounougalé Bagaye Bourmaye Dougssigui Gounou Ndolo Aguia Tchilang Kouroumla Kombou Nergué Kolon Laï Batouba Monogoy Darbé Bélé Zamré Dongor Djouni Koubno Bémaye Koli Banga Ngété Tandjile Goun Nanguéré Tandjilé Dimedou Gélgou Bongor Madbo Ouest Nangom Dar Gandil Dogou Dogo Damdou Ngolo Tchapadjigué Semaïndi Layane Béré Delim Kélo Dombala Tchoua Doromo Pont-Carol Dar Manga Beyssoa Manaï I Baguidja Bormane Koussaki Berdé Tandjilé Est Guidari Tandjilé Guessa Birboti Tchagra Moussoum Gabri Ngolo Kabladé Kasélem Centre Koukwala Toki Béro Manga Barmin Marbelem Koumabodan Ter Kokro Mouroum Dono-Manga Dono Manga Nantissa Touloum Kalité Bayam Kaga Palpaye Mandoul Dalé Langué Delbian Oriental Tchagra Belimdi Kariadeboum Dilati Lao Nongara Manga Dongo Bitikim Kangnéra Tchaouen Bédélé Kakerti Kordo Nangasou Bir Madang Kemkono Moni Bébala I Malaré Bologo Bélé Koro Garmaoa Alala Bissigri Dotomadi Karangoye Dadjilé Saar-Gogne Bala Kaye Mossoum Ngambo Mossoum -

FAO Desert Locust Bulletin 192 (English)

page 1 / 7 FAO EMERGENCY CENTRE FOR LOCUST OPERATIONS DESERT LOCUST BULLETIN No. 192 GENERAL SITUATION DURING AUGUST 1994 FORECAST UNTIL MID-OCTOBER 1994 No significant Desert Locust populations have been reported during August and the overall situation whilst still requiring vigilance, appears calm, with no major chance to develop during the forecast period. In West Africa, only scattered adults and hoppers were reported limited primarily to southern Mauritania. This would indicate that swarms from northern Mauritania dispersed earlier in the year before the onset of the rainy season and, as a result, breeding in the south was limited. No other significant locust activity has been reported from Mali, Niger and Chad. In South- West Asia, a few patches of hoppers have been treated in Rajasthan over a small area, and low density adults persisting in several locations of the summer breeding areas of India and Pakistan are likely to continue to breed; however, no major developments are expected during the forecast period. A few mature adults have been reported in the extreme south-eastern desert of Egypt and some isolated adults were present on the northern coastal plains of Somalia in late July. No locusts were reported from Sudan, Saudi Arabia, Yemen or Oman. Conditions were reported as dry in Algeria and no locust activity was reported; a similar situation is expected to prevail in Morocco. Although the overall situation does not appear to be critical and may decline in the next few months, FAO recommends continued monitoring in the summer breeding areas. The FAO Desert Locust Bulletin is issued monthly, supplemented by Updates during periods of increased Desert Locust activity, and is distributed by fax, telex, e-mail, FAO pouch and airmail by the Emergency Centre for Locust Operations, AGP Division, FAO, 00100 Rome, Italy. -

The Contribution of the Catholic Church to Post-Civil War Conflict Resolution in Chad

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Jesuit School of Theology Dissertations Student Scholarship 5-2020 The Contribution of the Catholic Church to Post-Civil War Conflict Resolution in Chad Rimasbé Dionbo Jean Claude Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/jst_dissertations Part of the Religion Commons THE CONTRIBUTION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH TO POST-CIVIL WAR CONFLICT RESOLUTION IN CHAD A Thesis by Rimasbé Dionbo Jean Claude presented to The Faculty of the Jesuit School of Theology of Santa Clara University in Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of the Licentiate in Sacred Theology Berkeley, California May 2020 Committee Signatures Julie Hanlon Rubio, PHD, Director Date Prof. Paul Thissen, PHD, Reader Date i Contents Contents ........................................................................................................................................... i Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ v Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................... vi Dedication ..................................................................................................................................... vii Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................... viii General Introduction ..................................................................................................................... -

To Arrest Or Not to Arrest the Incumbent Head of State: the Bashir Case and the Interplay Between Law and Politics

TO ARREST OR NOT TO ARREST THE INCUMBENT HEAD OF STATE: THE BASHIR CASE AND THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN LAW AND POLITICS JADRANKA PETROVIC,* DALE STEPHENS,** VASKO NASTEVSKI*** ABSTRACT In 2009, Sudanese President Omar Hassan Ahmad Al Bashir (‘President Bashir’) was indicted by the International Criminal Court (‘ICC’) on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity over the conflict in the western region of Darfur, Sudan. The following year the ICC charged President Bashir with genocide over events in Darfur, where allegedly more than 300 000 people have died and more than two million people have been displaced since 2003. Before the ICC can prosecute President Bashir, it has to obtain custody over him. As a judicial institution without power to arrest those it indicts, the Court relies on national authorities. States to which President Bashir has travelled since the warrants for his arrest have been issued have been reluctant to arrest and surrender President Bashir to the ICC justifying their refusal by the head of state immunity argument. By focusing on the specific response of the South African government to the ICC’s arrest warrant against President Bashir in June 2015, this article considers the question of whether states must cooperate with the ICC in instances of an arrest warrant against a sitting head of state of a non-state party and observes the broader implications of state responses similar to the South African case. I INTRODUCTION If Bashir were to come to South Africa today, we will definitely implement what we are supposed to in order to bring the culprit to [The] Hague. -

Myr 2010 Chad.Pdf

ORGANIZATIONS PARTICIPATING IN CONSOLIDATED APPEAL CHAD ACF CSSI IRD UNDP ACTED EIRENE Islamic Relief Worldwide UNDSS ADRA FAO JRS UNESCO Africare Feed the Children The Johanniter UNFPA AIRSERV FEWSNET LWF/ACT UNHCR APLFT FTP Mercy Corps UNICEF Architectes de l’Urgence GOAL NRC URD ASF GTZ/PRODABO OCHA WFP AVSI Handicap International OHCHR WHO BASE HELP OXFAM World Concern Development Organization CARE HIAS OXFAM Intermon World Concern International CARITAS/SECADEV IMC Première Urgence World Vision International CCO IMMAP Save the Children Observers: CONCERN Worldwide INTERNEWS Sauver les Enfants de la Rue International Committee of COOPI INTERSOS the Red Cross (ICRC) Solidarités CORD IOM Médecins Sans Frontières UNAIDS CRS IRC (MSF) – CH, F, NL, Lux TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................................. 1 Table I: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by cluster) ................................................... 3 Table II: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by appealing organization).......................... 4 Table III: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by priority)................................................... 5 2. CHANGES IN THE CONTEXT, HUMANITARIAN NEEDS AND RESPONSE ........................................... 6 3. PROGRESS TOWARDS ACHIEVING STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES AND SECTORAL TARGETS .......... 9 3.1 STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................................