Delalorm, Cephas (2016) Documentation and Description of Sɛkpɛlé: a Ghana-Togo Mountain Language of Ghana . Phd Thesis. SOAS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Field Test of New Features & Adaptations Based on On- Going Feedback

FIELD TEST OF NEW FEATURES & ADAPTATIONS BASED ON ON- GOING FEEDBACK USAID/GHANA JUSTICE SECTOR REFORM CASE TRACKING SYSTEM ACTIVITY October 29, 2019 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. FIELD TEST OF NEW FEATURES & ADAPTATIONS BASED ON ON- GOING FEEDBACK USAID/GHANA JUSTICE SECTOR REFORM CASE TRACKING SYSTEM ACTIVITY Contract No. AID-OOA-I-13-00032, Task Order No. 72064118F00001 Cover photo: Training session for staff of the Economic and Organised Crime Office (EOCO), Ho regional office on 14 May 2019. (Credit: Samuel Akrofi, Ghana Case Tracking System Activity) I FIELD TEST OF NEW FEATURES & ADAPTATIONS BASED ON ON-GOING FEEDBACK ACRONYMS ADKAR Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, Reinforcement BNI Bureau of National Investigations CLIN Contract Line Item Number CTS Case Tracking System EOCO Economic and Organized Crime Office FDA Food and Drug Authority FP Focal Point GoG Government of Ghana IBG Inter-regional Bridge Group ICT Information and Communications Technology GPoS Ghana Police Service GPrS Ghana Prison Service GRA Ghana Revenue Authority JSG Judicial Service of Ghana KSA Key Stakeholder Agency LAC Legal Aid Commission MOJ/DPP Ministry of Justice/Department of Public Prosecution PWA Performance Work Statement SGI Security and Governance Initiative SIE System Implementation Engineer(s) TDA Transnational Development Associates UAT user acceptance test USAID United States Agency for International Development TABLE OF -

BY DOE HEDE RICHMOND B.Ed (MATHEMATICS) a Thesis

LOCATION OF NON-OBNOXIOUS FACILITY (HOSPITAL) IN KETU SOUTH DISTRICT BY DOE HEDE RICHMOND B.Ed (MATHEMATICS) A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Mathematics, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Award of Master of Science in Industrial Mathematics. OF COLLEGE OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES INSTITUTE OF DISTANCE LEARNING MAY, 2013 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is the result of my own original research with close supervisor by my supervisor and that no part of it has been presented to any institution or organization anywhere for the award of Mastersdegree. All inclusive for the work of others has been duly acknowledged. Doe Hede Richmond (PG4065110) Student …………………… ………………… Signature Date Certified by; Mr. K. F. Darkwah Supervisor’s …………………… ………………… Signature Date Certified by; Mr. K. F. Darkwah …………………… ………………… Head of Department Signature Date ii ABSTRACT The main purpose of this research is to model the location of two emergency hospitals for Ketu South district due to the newness of the district. This is to help solve the immediate health needs of the people in the district. One essential way of doing this is to locate two hospitals which will be closer to all the towns and villages in order to reduce the cost of travelling and the distances people have to access the facilities (hospital). In doing this, p-median and heuristics(RH1, RH2 and RRH) were employed to minimize the distances people have to travel to the demand point (hospitals) to access the facilities. Floyd-warshall algorithm was also adopted to connect the ten (10) selected towns and villages together. -

Country: Ghana Language: D G (Mo) Description: Bible 1St Edition

Country: Ghana Language: D g (Mo) Description: Bible 1st edition Speakers: 55,000 Translators: Noah Ampem, Gabriel Chiu, Stephen Kofi Mensah, Began: 1981 Wilfred Opoku, Edward Banchagla, Joshua Osei Translation Consultant: Marjorie Crouch Published: 2015 Literacy Specialist: Patricia Herbert Editorial Consultant: Margaret Langdon Dedication: March 2016 Naa Dr Tebala kala Gyasehene thanking God for the Deg Bible Most Dega people live in Dega Hare (Dega land) which The people call themselves, Dega, meaning “multiply- is located in the Bole district in the Northern Region ing”, “spreading quickly”, or “fertility”. One person is and the Wenchi and Kintampo districts in the Brong called a Deg and the language is also known as Deg. Ahafo Region. Dega Hare consists of about 46 villag- Other ethnic groups in Ghana call the Dega, Mo, “the es in an area roughly 650 square miles (about the size people who did well”. It’s believed that this name, Mo, of Union County in North Carolina). Outside Dega acknowledges an event where the Dega came to the aid Hare, there are a number of Dega people in the Jaman of another Ghanaian tribe in battle, who would have District in Ghana. A group also lives in several villages been defeated without the valiant efforts of the Dega. in Cote d’lvoire and Dega in Ghana call those people Lamoolatina (the people beyond the river). [continued] Even before Christianity or Islam came to Dega weak and impure human beings in need of a power Hare, Dega acknowledged the existence of God, the not their own to know Him… it seemed, this God, Supreme Being. -

“I Want to Go to School, but I Can't”: Examining the Factors That Impact

―I Want to go to School, but I Can‘t‖: Examining the Factors that Impact the Anlo Ewe Girl Child‘s Formal Education in Abor, Ghana A dissertation presented to the faculty of The Gladys W. and David H. Patton College of Education and Human Services of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Karen Yawa Agbemabiese-Grooms August 2011 © 2011 Karen Yawa Agbemabiese-Grooms. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled ―I Want to go to School, but I Can‘t‖: Examining the Factors that Impact the Anlo Ewe Girl Child‘s Formal Education in Abor, Ghana by KAREN YAWA AGBEMABIESE-GROOMS has been approved for the Department of Educational Studies and The Gladys W. and David H. Patton College of Education and Human Services by Jaylynne N. Hutchinson Associate Professor of Educational Studies Renée A. Middleton Dean, The Gladys W. and David H. Patton College of Education and Human Services 3 Abstract AGBEMABIESE-GROOMS, KAREN YAWA, Ph.D., August 2011, Curriculum and Instruction, Cultural Studies ―I Want to go to School, but I Can‘t‖: Examining the Factors that Impact the Anlo Ewe Girl Child‘s Formal Education in Abor, Ghana (pp. 306) Director of Dissertation: Jaylynne N. Hutchinson This study explored factors that impact the Anlo Ewe girl child‘s formal educational outcomes. The issue of female and girl child education is a global concern even though its undesirable impact is more pronounced in African rural communities (Akyeampong, 2001; Nukunya, 2003). Although educational research in Ghana indicates that there are variables that limit girl‘s access to formal education, educational improvements are not consistent in remedying the gender inequities in education. -

University of Education, Winneba College Of

University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION, WINNEBA COLLEGE OF LANGUAGES EDUCATION, AJUMAKO THE SYNTAX OF THE GONJA NOUN PHRASE JACOB SHAIBU KOTOCHI May, 2017 i University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION, WINNEBA COLLEGE OF LANGUAGES EDUCATION, AJUMAKO THE SYNTAX OF THE GONJA NOUN PHRASE JACOB SHAIBU KOTOCHI 8150260007 A thesis in the Department of GUR-GONJA LANGUAGES EDUCATION, COLLEGE OF LANGUAGES EDUCATION, submitted to the school of Graduate Studies, UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION, WINNEBA in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the Master of Philosophy in Ghanaian Language Studies (GONJA) degree. ii University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh DECLARATION I, Jacob Shaibu Kotochi, declare that this thesis, with the exception of quotations and references contained in published works and students creative writings which have all been identified and duly acknowledged, is entirely my own original work, and it has not been submitted, either in part or whole, for another degree elsewhere. Signature: …………………………….. Date: …………………………….. SUPERVISOR’S DECLARATION I, Dr. Samuel Awinkene Atintono, hereby declare that the preparation and presentation of this thesis were supervised in accordance with the guidelines for supervision of thesis as laid down by the University of Education, Winneba. Signature: …………………………….. Date: …………………………….. iii University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to express my gratitude to Dr. Samuel Awinkene Atintono of the Department of Gur-Gonja Languages Education, College of Languages Education for being my guardian, mentor, lecturer and supervisor throughout my university Education and the writing of this research work. -

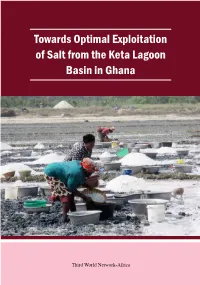

Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana

Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana Third World Network-Africa Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana Third World Network-Africa Accra, Ghana Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana is published by Third World Network-Africa No 9 Asmara Street, East Legon, Accra Box AN 19452, Accra, Ghana Tel: 233-302-500419/503669/511189 Website: www.twnafrica.org Email: [email protected] Copyright © Third World Network-Africa, 2017 ISBN: 9988271305 Foreword Ghana has the best endowment for and is the biggest producer of solar salt in West Africa. The bulk of the production and export comes from arti- sanal and small scale (ASM) producers. This is a research report on strug- gles between a large scale salt company and some communities around the Keta Lagoon in Ghana. At the centre of the conflict is the disruption of the livelihoods of the communities by the award of a concession to a foreign investor for large scale salt production, an act which has expropri- ated what the communities see as the commons around the lagoon where for generations they have carried out livelihood activities which combine fishing, farming and salt production. The Keta Lagoon is the second most important salt producing area in Ghana and the conflict, in which Police protecting the company have shot some locals dead, is emblematic of the wider problem of the status of ASM across Africa with many governments even when faced with the huge potential of ASM avoid offering support to these predominantly lo- cal entrepreneurs and reflexively choose to support large scale, usually foreign, investors. -

Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African Languages

Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African Languages UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African Languages Gerrit J. Dimmendaal University of Cologne John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American 8 National Standard for Information Sciences — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dimmendaal, Gerrit Jan. Historical linguistics and the comparative study of African languages / Gerrit J. Dimmendaal. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. African languages--Grammar, Comparative. 2. Historical linguistics. I. Title. PL8008.D56 2011 496--dc22 2011002759 isbn 978 90 272 1178 1 (Hb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 1179 8 (Pb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 8722 9 (Eb) © 2011 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. John Benjamins Publishing Company • P.O. Box 36224 • 1020 me Amsterdam • The Netherlands John Benjamins North America • P.O. Box 27519 • Philadelphia PA 19118-0519 • USA UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs Table of contents Preface ix Figures xiii Maps xv Tables -

Works of Russell G. Schuh

UCLA Works of Russell G. Schuh Title Schuhschrift: Papers in Honor of Russell Schuh Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7c42d7th ISBN 978-1-7338701-1-5 Publication Date 2019-09-05 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7c42d7th#supplemental Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Schuhschrift Margit Bowler, Philip T. Duncan, Travis Major, & Harold Torrence Schuhschrift Papers in Honor of Russell Schuh eScholarship Publishing, University of California Margit Bowler, Philip T. Duncan, Travis Major, & Harold Torrence (eds.). 2019. Schuhschrift: Papers in Honor of Russell Schuh. eScholarship Publishing. Copyright ©2019 the authors This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Interna- tional License. To view a copy of this license, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. ISBN: 978-1-7338701-1-5 (Digital) 978-1-7338701-0-8 (Paperback) Cover design: Allegra Baxter Typesetting: Andrew McKenzie, Zhongshi Xu, Meng Yang, Z. L. Zhou, & the editors Fonts: Gill Sans, Cardo Typesetting software: LATEX Published in the United States by eScholarship Publishing, University of California Contents Preface ix Harold Torrence 1 Reason questions in Ewe 1 Leston Chandler Buell 1.1 Introduction . 1 1.2 A morphological asymmetry . 2 1.3 Direct insertion of núkàtà in the left periphery . 6 1.3.1 Negation . 8 1.3.2 VP nominalization fronting . 10 1.4 Higher than focus . 12 1.5 Conclusion . 13 2 A case for “slow linguistics” 15 Bernard Caron 2.1 Introduction . -

ED373534.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 373 534 FL 022 094 AUTHOR Bodomo, Adams B. TITLE Complex Predicates and Event Structure: An Integrated Analysis of Serial Verb Constructions in the Mabia Languages of West Africa. Working Papers in Linguistics No. 20. INSTITUTION Trondheim Univ. (Norway). Dept. of Linguistics. REPORT NO ISSN-0802-3956 PUB DATE 93 NOTE 148p.; Thesis, University of Trondheim, Norway. Map on page 110 may not reproduce well. PUB TYPE Dissertations/Theses Undetermined (040) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *African Languages; Foreign Countries; *Grammar; *Language Patterns; Language Research; Language Variation; *Semantics; Structural Analysis (Linguistics); *Syntax; Uncommonly Taught Languages; *Verbs IDENTIFIERS Africa (West); Dagari ABSTRACT An integrated analysis of the syntax and semantics of serial verb constructions (SVCs) in a group of West African languages is presented. With data from Dagadre and closest relatives, a structural definition for SVCs is developed (two or more lexical verbs that share grammatical categories within a clause), establishing SVCs as complex predicates. Based on syntactic theories, a formal phrase structure is adapted forrepresentation of SVCs, interpreting each as a product of a series of VP adjunctions. Within this new, non-derivational, pro-expansionary approach to grammar, several principles are developed to license grammatical information flow and verbal ordering priority. Based on semantic theories, a functional account of SVCs is developed: that the actions represented by the verbs in the SVC together express a single, complex event. A new model of e. -ant structure for allconstructional transitions is proposed, and it is illustrated how two types of these transitions, West African SVCs and Scandinavian small clause constructions(SCCs), conform to this proposed event structure. -

Certified Electrical Wiring Professionals Volta Regional Register Certification No

CERTIFIED ELECTRICAL WIRING PROFESSIONALS VOLTA REGIONAL REGISTER CERTIFICATION NO. NAME PHONE NUMBER PLACE OF WORK PIN NUMBER CLASS 1 ABOTSI FELIX GBOMOSHOW 0246296692 DENU EC/CEWP1/06/18/0020 DOMESTIC 2 ACKUAYI JOSEPH DOTSE 0244114574 ANYAKO EC/CEWP1/12/14/0021 DOMESTIC 3 ADANU KWASHIE WISDOM 0245768361 DZODZE, VOLTA REGION EC/CEWP1/06/16/0025 DOMESTIC 4 ADEVOR FRANCIS 0241658220 AVE-DAKPA EC/CEWP1/12/19/0013 DOMESTIC 5 ADISENU ADOLF QUARSHIE 0246627858 AGBOZUME EC/CEWP1/12/14/0039 DOMESTIC 6 ADJEI-DZIDE FRANKLIN ELENUJOR NOVA KING 0247928015 KPANDO, VOLTA EC/CEWP1/12/18/0025 DOMESTIC 7 ADOR AFEAFA 0246740864 SOGAKOPE EC/CEWP1/12/19/0018 DOMESTIC 8 ADZALI PAUL KOMLA 0245789340 TAFI MADOR EC/CEWP1/12/14/0054 DOMESTIC 9 ADZAMOA DIVINE MENSAH 0242769759 KRACHI EC/CEWP1/12/18/0031 DOMESTIC 10 ADZRAKU DODZI 0248682929 ALAVANYO EC/CEWP1/12/18/0033 DOMESTIC 11 AFADZINOO MIDAWO 0243650148 ANLO AFIADENYIGBA EC/CEWP1/06/14/0174 DOMESTIC 12 AFUTU BRIGHT 0245156375 HOHOE EC/CEWP1/12/18/0035 DOMESTIC 13 AGBALENYO CHRISTIAN KOFI 0285167920 ANLOKODZI, HO EC/CEWP1/12/13/0024 DOMESTIC 14 AGBAVE KINDNESS JERRY 0505231782 AKATSI, VOLTA REGION EC/CEWP1/12/15/0040 DOMESTIC 15 AGBAVOR SIMON 0243436475 KPANDO EC/CEWP1/12/16/0050 DOMESTIC 16 AGBAVOR VICTOR KWAKU 0244298648 AKATSI EC/CEWP1/06/14/0177 DOMESTIC 17 AGBEKO MICHEAL 0557912356 SOGAKOFE EC/CEWP1/06/19/0095 DOMESTIC 18 AGBEMADE SIMON 0244049157 DABALA, SOGAKOPE,VOLTA REGIONEC/CEWP1/12/16/0052 DOMESTIC 19 AGBEMAFLE MICHAEL 0248481385 HOHOE EC/CEWP1/12/18/0038 DOMESTIC 20 AGBENORKU KWAKU EMMANUEL 0506820579 DABALA JUNCTION- SOGAKOPE, VOLEC/CEWP1/12/17/0053 DOMESTIC 21 AGBENYEFIA SENANU FRANCIS 0244937008 CENTRAL TONGU EC/CEWP1/06/17/0046 DOMESTIC 22 AGBODOVI K. -

Report of the Ghana DECCMA Launch and Inception Workshop, 6Th May 2014

Workshop Report Report of the Ghana DECCMA launch and inception workshop, 6th May 2014 DECCMA Ghana team Citation: DECCMA Ghana. 2014. Report of the Ghana DECCMA launch and inception workshop, 6th May 2014. DECCMA Working Paper, Deltas, Vulnerability and Climate Change: Migration and Adaptation, IDRC Project Number 107642. Available online at: www.deccma.com, date accessed About DECCMA Working Papers This series is based on the work of the Deltas, Vulnerability and Climate Change: Migration and Adaptation (DECCMA) project, funded by Canada’s International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) through the Collaborative Adaptation Research Initiative in Africa and Asia (CARIAA). CARIAA aims to build the resilience of vulnerable populations and their livelihoods in three climate change hot spots in Africa and Asia. The program supports collaborative research to inform adaptation policy and practice. Titles in this series are intended to share initial findings and lessons from research studies commissioned by the program. Papers are intended to foster exchange and dialogue within science and policy circles concerned with climate change adaptation in vulnerability hotspots. As an interim output of the DECCMA project, they have not undergone an external review process. Opinions stated are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policies or opinions of IDRC, DFID, or partners. Feedback is welcomed as a means to strengthen these works: some may later be revised for peer-reviewed publication. Contact Sam Codjoe [email protected] Creative Commons License This Working Paper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. -

The Acoustic Correlates of Atr Harmony in Seven- and Nine

THE ACOUSTIC CORRELATES OF ATR HARMONY IN SEVEN- AND NINE- VOWEL AFRICAN LANGUAGES: A PHONETIC INQUIRY INTO PHONOLOGICAL STRUCTURE by COLEEN GRACE ANDERSON STARWALT Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2008 Copyright © by Coleen G. A. Starwalt 2008 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To Dad who told me I could become whatever I set my mind to (May 6, 1927 – April 17, 2008) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Where does one begin to acknowledge those who have walked alongside one on a long and often lonely journey to the completion of a dissertation? My journey begins more than ten years ago while at a “paper writing” workshop in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. I was consulting with Rod Casali on a paper about Ikposo [ATR] harmony when I casually mentioned my desire to do an advanced degree in missiology. Rod in his calm and gentle way asked, “Have you ever considered a Ph.D. in linguistics?” I was stunned, but quickly recoverd with a quip: “Linguistics!? That’s for smart people!” Rod reassured me that I had what it takes to be a linguist. And so I am grateful for those, like Rod, who have seen in me things that I could not see for myself and helped to draw them out. Then the One Who Directs My Steps led me back to the University of Texas at Arlington where I found in David Silva a reflection of the adage “deep calls to deep.” For David, more than anyone else during my time at UTA, has drawn out the deep things and helped me to give them shape and meaning.