“I Want to Go to School, but I Can't”: Examining the Factors That Impact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Field Test of New Features & Adaptations Based on On- Going Feedback

FIELD TEST OF NEW FEATURES & ADAPTATIONS BASED ON ON- GOING FEEDBACK USAID/GHANA JUSTICE SECTOR REFORM CASE TRACKING SYSTEM ACTIVITY October 29, 2019 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. FIELD TEST OF NEW FEATURES & ADAPTATIONS BASED ON ON- GOING FEEDBACK USAID/GHANA JUSTICE SECTOR REFORM CASE TRACKING SYSTEM ACTIVITY Contract No. AID-OOA-I-13-00032, Task Order No. 72064118F00001 Cover photo: Training session for staff of the Economic and Organised Crime Office (EOCO), Ho regional office on 14 May 2019. (Credit: Samuel Akrofi, Ghana Case Tracking System Activity) I FIELD TEST OF NEW FEATURES & ADAPTATIONS BASED ON ON-GOING FEEDBACK ACRONYMS ADKAR Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, Reinforcement BNI Bureau of National Investigations CLIN Contract Line Item Number CTS Case Tracking System EOCO Economic and Organized Crime Office FDA Food and Drug Authority FP Focal Point GoG Government of Ghana IBG Inter-regional Bridge Group ICT Information and Communications Technology GPoS Ghana Police Service GPrS Ghana Prison Service GRA Ghana Revenue Authority JSG Judicial Service of Ghana KSA Key Stakeholder Agency LAC Legal Aid Commission MOJ/DPP Ministry of Justice/Department of Public Prosecution PWA Performance Work Statement SGI Security and Governance Initiative SIE System Implementation Engineer(s) TDA Transnational Development Associates UAT user acceptance test USAID United States Agency for International Development TABLE OF -

BY DOE HEDE RICHMOND B.Ed (MATHEMATICS) a Thesis

LOCATION OF NON-OBNOXIOUS FACILITY (HOSPITAL) IN KETU SOUTH DISTRICT BY DOE HEDE RICHMOND B.Ed (MATHEMATICS) A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Mathematics, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Award of Master of Science in Industrial Mathematics. OF COLLEGE OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES INSTITUTE OF DISTANCE LEARNING MAY, 2013 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is the result of my own original research with close supervisor by my supervisor and that no part of it has been presented to any institution or organization anywhere for the award of Mastersdegree. All inclusive for the work of others has been duly acknowledged. Doe Hede Richmond (PG4065110) Student …………………… ………………… Signature Date Certified by; Mr. K. F. Darkwah Supervisor’s …………………… ………………… Signature Date Certified by; Mr. K. F. Darkwah …………………… ………………… Head of Department Signature Date ii ABSTRACT The main purpose of this research is to model the location of two emergency hospitals for Ketu South district due to the newness of the district. This is to help solve the immediate health needs of the people in the district. One essential way of doing this is to locate two hospitals which will be closer to all the towns and villages in order to reduce the cost of travelling and the distances people have to access the facilities (hospital). In doing this, p-median and heuristics(RH1, RH2 and RRH) were employed to minimize the distances people have to travel to the demand point (hospitals) to access the facilities. Floyd-warshall algorithm was also adopted to connect the ten (10) selected towns and villages together. -

Be a Friend of Moja

Najee October 7 The Gaillard Center 95 Calhoun Street Having collaborated with everyone in the music business from Prince and Quincy Jones to Stevie Wonder, Chaka Khan and Herbie Hancock, Najee’s technical agility, grace, compositional prowess, unbridled passion and fearless genre bending have made him one of the most sought after musicians of his generation. 2011MOJA Program Book_2004 MOJA Program Book 9/12/11 9:54 PM Page 2 City of Charleston South Carolina DEAR MOJADear MOJA FESTIVAL Festival Guests: GUESTS: Welcome to MOJA,Welcome Charleston’sto the 2011 MOJA annual Arts Festival, celebration Charleston’s annualof African-American celebration of African- and Carib- American and Caribbean Arts and Culture, produced by the City of Charleston Office of bean arts andCultural culture! Affairs. The 2016 MOJA Arts Festival assembles an amazing array of talents and traditions, affording locals and visitors alike the opportunity to celebrate This year’s festival highlights include: An Evening of Jazz Under the Stars with Najee at the cultural heritagePorter-Gaud and School artistic Stadium (pg.vitality 10); City of Gallery the Lowcountry.at Waterfront Park exhibitionProudly “Special produced by the Moments: Works From the Collection of Dr. Harold Rhodes, III” (pg. 27); A Classical City of CharlestonEncounter Office with Eleganza of atCultural the City GalleryAffairs at Waterfront in a longstanding Park followed by a champagnepartnership with the all-volunteer MOJAreception Arts(pg. 11); Festival Mt. Zion PlanningSpiritual Singers’ Committee, soul stirring Camp year Meeting after (pg. year 11); MOJA an brings enchanting evening of dance by PHILADANCO at the Gaillard Auditorium (pg. 7); Gwen Charleston togetherButler’s jazz as cruise we on gather the Charleston and Harborengage aboard in the festive Spirit of Charlestonperformances, (pg. -

Annual AT&T San Jose Jazz Summer Fest Friday, August 12

***For Immediate Release*** 22nd Annual AT&T San Jose Jazz Summer Fest Friday, August 12 - Sunday, August 14, 2011 Plaza de Cesar Chavez Park, Downtown San Jose, CA Ticket Info: www.jazzfest.sanjosejazz.org Tickets: $15 - $20, Children Under 12 Free "The annual San Jose Jazz [Summer Fest] has grown to become one of the premier music events in this country. San Jose Jazz has also created many educational programs that have helped over 100,000 students to learn about music, and to become better musicians and better people." -Quincy Jones "Folks from all around the Bay Area flock to this giant block party… There's something ritualesque about the San Jose Jazz [Summer Fest.]" -Richard Scheinan, San Jose Mercury News "San Jose Jazz deserves a good deal of credit for spotting some of the region's most exciting artists long before they're headliners." -Andy Gilbert, San Jose Mercury News "Over 1,000 artists and 100,000 music lovers converge on San Jose for a weekend of jazz, funk, fusion, blues, salsa, Latin, R&B, electronica and many other forms of contemporary music." -KQED "…the festival continues to up the ante with the roster of about 80 performers that encompasses everything from marquee names to unique up and comers, and both national and local acts...." -Heather Zimmerman, Silicon Valley Community Newspapers San Jose, CA - June 15, 2011 - San Jose Jazz continues its rich tradition of presenting some of today's most distinguished artists and hottest jazz upstarts at the 22nd San Jose Jazz Summer Fest from Friday, August 12 through Sunday, August 14, 2011 at Plaza de Cesar Chavez Park in downtown San Jose, CA. -

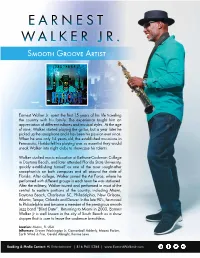

Earnest Walker Jr

EARNEST WALKER JR. Smooth Groove Artist Earnest Walker Jr. spent the first 15 years of his life traveling the country with his family. The experience taught him an appreciation of different cultures and musical styles. At the age of nine, Walker started playing the guitar, but a year later he picked up the saxophone and it has been his passion ever since. When he was only 14 years old, the established musicians in Pensacola, Florida felt his playing was so essential they would sneak Walker into night clubs to showcase his talents. Walker studied music education at Bethune-Cookman College in Daytona Beach, and later attended Florida State University, quickly establishing himself as one of the most sought-after saxophonists on both campuses and all around the state of Florida. After college, Walker joined the Air Force, where he performed with different groups in each town he was stationed. After the military, Walker toured and performed in most of the central to eastern portions of the country, including Miami, Daytona Beach, Charleston SC, Philadelphia, New Orleans, Atlanta, Tampa, Orlando and Denver. In the late 90’s, he moved to Philadelphia and became a member of the prestigious smooth jazz band “Blind Date”. Returning to Miami in 2003, Earnest Walker Jr is well known in the city of South Beach as a show stopper that is sure to leave the audience breathless. Location: Miami, FL USA Influences: Grover Washington Jr, Cannonball Adderly, Maceo Parker, Earth Wind & Fire, Gerald Albright, Ronnie Laws Booking & Media Contact: HJ Entertainment | 816.945.0288 | www.EarnestWalkerJr.com ON STAGE As solid, compelling and in the pocket as Walker is on disc, he’s best known in the jazz world as a powerhouse performer whose stage presence and creative style guarantees that every crowd is in an uproar. -

CASH BOX JAZZ ALBUMS Only Representatives of the Last 25 Years

— C-i 1 ON JAZZ \ CASH BOX JAZZ ALBUMS only representatives of the last 25 years in jazz, by the way) — is the place to go Title, Artist, Label, Number, Distributor for anybody who wants to learn about = Available on Compact Disc LB = Platinum (RIAA Certified) jazz, to hear how Louis Armstrong | W| ( = Gold (RIAA Certified) MANHATTAN BURN 23 V relates to Charlie Parker, how Char- El W PAQUITO D'RIVERA (Columbia FC lie Parker relates to Ornette Cole- L O 40583) 22 FULTON STREET MAUL etc. It is an indispensable W C man, TIM BERNE (Columbia FC 40530) NAJEE’S THEME * 2 19 collection and it is available from Smith- CLOUD ABOUT NAJEE (EMI ST 17241) El sonian Collection of Recordings, P.O. MERCURY* A CHANGE OF HEART * 1 11 DAVID TORN WITH MARK 1SHAM, DAVID SANBORN (Warner Bros. Box 23345, Washington, D.C. 20026. TONY LEVIN. BILL BRUFORD (ECM 27479-1) 831 108) SPARE CHANGE— I wrote a couple THE OTHER SIDE OF 18 EJ LADY FROM BRAZIL* MAXINE AND CO. - The late Maxine of weeks ago in this space about the ROUND MIDNIGHT TANIA MARIA (Manhattan ST 53045) at Holly- FEATURING DEXTER 25 GOOD MORNING KISS Sullivan was joined during a gig the new Bluebird and Novus reissues RCA GORDON * CARMEN LUNDY (Blackhawke BKH wood Roosevelt's Cinegrill earlier this year ai d issues, but I’d like to add a couple (Blue Note BT 85135) _ 523) 1 by fellow vocalists Diane Schuur (I) and Nellie A NICE PLACE TO BE 20 fzl REUNITED Dri of things. -

Festival 2021

ARTS ACADEMY FESTIVAL 2 021 Interlochen Center for the Arts, a recipient of the National Medal of Arts, is a global arts organization that includes: • Interlochen Arts Academy - Arts boarding high school with Academy Fact Sheet rigorous college-prep academics • Interlochen Arts Camp - 59th Year | August 2020 - May 2021 Summer arts programs for grades 3-12 • College of Creative Arts - Lifelong learning in the arts Total Enrollment Classes • Interlochen Public Radio - 545 Students Freshman 50 Two stations: Classical Music and News (NPR Member Station) Sophomore 95 46 U.S. states and territories Junior 165 • Interlochen Presents - presenting more than 600 events annaully represented Senior 213 featuring students, faculty, and Post-graduate 22 internationally recognized guest artists. Top state delegations: • Interlochen Online - a virtual State Students Residential Status platform that brings the world- Michigan 104 Boarding 503 renowned Interlochen experience Day Students 42 into your home, building a virtual California 32 bridge of connection to the world’s New York 26 leading arts educators. Arts Areas Florida 25 Creative Writing 25 Interlochen Arts Academy challenges Illinois 23 Dance 41 students to achieve artistically and Texas 19 Film & New Media 22 academically. Since 1980, 46 Arts Wisconsin 18 Interdisciplinary Arts 24 Academy students have been named Presidential Scholars, unmatched Ohio 17 Music 269 by any other high school in the country. Maryland 16 Theatre 109 Indiana 14 Visual Arts 55 Academy students create hundreds of presentations including student concerts, performances, exhibits, readings, and screenings. 20 countries and territories More than 300 faculty and staff work to maintain a positive and safe Angola 1 Korea 6 environment for all students. -

The BG News November 23, 1993

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 11-23-1993 The BG News November 23, 1993 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News November 23, 1993" (1993). BG News (Student Newspaper). 5617. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/5617 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. 4? The BG News Tuesday , November 23, 1993 Bowling Green, Ohio Volume 76, Issue 64 Briefs Handgun bill center of debate Weather The Associated Press clean up the savings and loan fi- baum, D-Ohio. over unanimous Republican op- an ambitious final-day agenda asco. President Clinton prodded position, and last week's approv- that ranged from the campaign lawmakers to deliver the bill for Sunny skies coming: The House approved a plan to al of the North American Free overhaul bill to a $90 billion WASHINGTON - After a year remake the campaign finance his signature as a "Thanksgiving Trade Agreement. package of spending cuts to less marked by swings from confron- laws, a key item on President Day present" to a crime-weary Today, partly sunny. High Rep. Bob Livingston, R-La, weighty concerns. Among them tation to cooperation, Congress Clinton's agenda. The 255-175 public. -

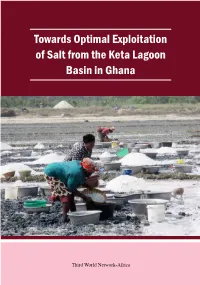

Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana

Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana Third World Network-Africa Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana Third World Network-Africa Accra, Ghana Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana is published by Third World Network-Africa No 9 Asmara Street, East Legon, Accra Box AN 19452, Accra, Ghana Tel: 233-302-500419/503669/511189 Website: www.twnafrica.org Email: [email protected] Copyright © Third World Network-Africa, 2017 ISBN: 9988271305 Foreword Ghana has the best endowment for and is the biggest producer of solar salt in West Africa. The bulk of the production and export comes from arti- sanal and small scale (ASM) producers. This is a research report on strug- gles between a large scale salt company and some communities around the Keta Lagoon in Ghana. At the centre of the conflict is the disruption of the livelihoods of the communities by the award of a concession to a foreign investor for large scale salt production, an act which has expropri- ated what the communities see as the commons around the lagoon where for generations they have carried out livelihood activities which combine fishing, farming and salt production. The Keta Lagoon is the second most important salt producing area in Ghana and the conflict, in which Police protecting the company have shot some locals dead, is emblematic of the wider problem of the status of ASM across Africa with many governments even when faced with the huge potential of ASM avoid offering support to these predominantly lo- cal entrepreneurs and reflexively choose to support large scale, usually foreign, investors. -

Certified Electrical Wiring Professionals Volta Regional Register Certification No

CERTIFIED ELECTRICAL WIRING PROFESSIONALS VOLTA REGIONAL REGISTER CERTIFICATION NO. NAME PHONE NUMBER PLACE OF WORK PIN NUMBER CLASS 1 ABOTSI FELIX GBOMOSHOW 0246296692 DENU EC/CEWP1/06/18/0020 DOMESTIC 2 ACKUAYI JOSEPH DOTSE 0244114574 ANYAKO EC/CEWP1/12/14/0021 DOMESTIC 3 ADANU KWASHIE WISDOM 0245768361 DZODZE, VOLTA REGION EC/CEWP1/06/16/0025 DOMESTIC 4 ADEVOR FRANCIS 0241658220 AVE-DAKPA EC/CEWP1/12/19/0013 DOMESTIC 5 ADISENU ADOLF QUARSHIE 0246627858 AGBOZUME EC/CEWP1/12/14/0039 DOMESTIC 6 ADJEI-DZIDE FRANKLIN ELENUJOR NOVA KING 0247928015 KPANDO, VOLTA EC/CEWP1/12/18/0025 DOMESTIC 7 ADOR AFEAFA 0246740864 SOGAKOPE EC/CEWP1/12/19/0018 DOMESTIC 8 ADZALI PAUL KOMLA 0245789340 TAFI MADOR EC/CEWP1/12/14/0054 DOMESTIC 9 ADZAMOA DIVINE MENSAH 0242769759 KRACHI EC/CEWP1/12/18/0031 DOMESTIC 10 ADZRAKU DODZI 0248682929 ALAVANYO EC/CEWP1/12/18/0033 DOMESTIC 11 AFADZINOO MIDAWO 0243650148 ANLO AFIADENYIGBA EC/CEWP1/06/14/0174 DOMESTIC 12 AFUTU BRIGHT 0245156375 HOHOE EC/CEWP1/12/18/0035 DOMESTIC 13 AGBALENYO CHRISTIAN KOFI 0285167920 ANLOKODZI, HO EC/CEWP1/12/13/0024 DOMESTIC 14 AGBAVE KINDNESS JERRY 0505231782 AKATSI, VOLTA REGION EC/CEWP1/12/15/0040 DOMESTIC 15 AGBAVOR SIMON 0243436475 KPANDO EC/CEWP1/12/16/0050 DOMESTIC 16 AGBAVOR VICTOR KWAKU 0244298648 AKATSI EC/CEWP1/06/14/0177 DOMESTIC 17 AGBEKO MICHEAL 0557912356 SOGAKOFE EC/CEWP1/06/19/0095 DOMESTIC 18 AGBEMADE SIMON 0244049157 DABALA, SOGAKOPE,VOLTA REGIONEC/CEWP1/12/16/0052 DOMESTIC 19 AGBEMAFLE MICHAEL 0248481385 HOHOE EC/CEWP1/12/18/0038 DOMESTIC 20 AGBENORKU KWAKU EMMANUEL 0506820579 DABALA JUNCTION- SOGAKOPE, VOLEC/CEWP1/12/17/0053 DOMESTIC 21 AGBENYEFIA SENANU FRANCIS 0244937008 CENTRAL TONGU EC/CEWP1/06/17/0046 DOMESTIC 22 AGBODOVI K. -

Watch/Listen to Najee and Meli'sa Morgan's 'In the Mood to Take It

Link: http://www.eurweb.com/2013/11/watchlisten-to-najee-and-melisa-morgans-in-the-mood-to- take-it-slow/ Watch/Listen to Najee and Meli’sa Morgan’s ‘In The Mood To Take It Slow’ November 5, 2013Entertainment *Platinum-selling and Grammy-winning saxophonist Najee has released his new CD, The Morning After – A Musical Love Journey on Shanachie Entertainment. The new CD includes a tribute to his dear friend George Duke as well as a great track with Meli’sa Morgan. Check out the track with Meli’sa Morgan below called “In The Mood To Take It Slow.” About Najee Najee is a master storyteller. Whether the debonair multi-instrumentalist is engaged in a verbal or musical conversation, his alluring charisma has a way of seducing you into his world. A quadruple threat who is equally adept on soprano, tenor and alto saxophones and flute, Najee’s technical agility, grace, compositional prowess, unbridled passion, fearless genre bending and superior musicianship have made him one of the most sought after musicians of his generation. In a business where trends and artists come and go, Najee’s name is synonymous with innovation, consistency and the best in contemporary jazz. With two Platinum and four Gold albums under his belt, he is an icon whose musical vision spawned an entire new genre by fusing the music close to his heart (R&B and jazz). Three decades later he is showing that he is not done yet! Najee has collaborated with everyone from Prince and Quincy Jones to Stevie Wonder, Chaka Khan and Herbie Hancock. -

Najee Ali' Was Dumped for Abusing His Wife Sentinel News Service Sentinel News Service Allegations Were False

2017 2017 THE YEAR THE YEAR IN IN REVIEW REVIEW VOL. LXXVV, NO. 49 • $1.00 + CA. Sales Tax THURSDAY, DECEMBERSEPTEMBER 12 17,- 18, 2015 2013 VOL. LXXXI NO 52 $1.00 +CA. Sales Tax“For Over “For Eighty Over Eighty Years YearsThe Voice The Voice of Our of CommunityOur Community Speaking Speaking for for Itself Itself” THURSDAY, DECEMBER 28, 2017 NAN Confirms Ronald Eskew aka 'Najee Ali' was dumped for abusing his wife SENTINEL NEWS SERVICE SENTINEL NEWS SERVICE allegations were false. Ronald Eskew (AKA However, Rev. Tulloss 171 Members of Con- Najee Ali) has spent the and National Action Net- gress, led by Congress- past two weeks trying to work released an official woman Maxine Waters minimize and spin his statement confirming that (CA-43), Ranking Mem- dismissal from National the reports written by Jas- ber of the House Financial Action Network. He myne Cannick were in fact Services Committee, sent a has attacked his friend true. letter to the Deputy Attor- and loyal supporter, the Controversy, criminal ney General of the United Reverend K.W. Tulloss, and inappropriate behav- States, Rod J. Rosenstein, both in publicly and in ior are nothing new for Ali. to express their support private, while trying to He has been denounced for the investigation be- deflect blame for his own COURTESY PHOTO and even involved in both ing conducted by Special malicious actions and de- Ronald Eskew verbal and physical al- Counsel Robert S. Muel- mons. tercations with members COURTESY OF THE OFFICE OF REP. MAXINE WATERS ler, III. Last week, the Senti- tions made by Najee's wife of several organizations.