Detroit Jazz Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sponsorships

An event benefitting the AP World Organization th SEPTEMBER 11 , 2021 PerformingBOB JAMES Artists PIECES OF A DREAM GERALD ALBRIGHT JAZZ FUNK SOUL MARION MEADOWS ALEX BUGNON JEFF BRADSHAW AND FRIENDS 114 S. New York Avenue, Atlantic City, New Jersey AP WORLD An 501c-3, tax deductible organization built on the legacy of a beloved son, doing our part to strengthen families and inspire communities during difficult times. Professional basketball player, DeAndre’ Bembry of the Toronto Raptors, launched AP World in memory of his brother, Adrian Potts. Adrian celebrated his brothers’ accomplishments and planned to be sitting alongside DeAndre’ to watch the NBA draft on June 23, 2016. Adrian helped plan the draft party with their mother, Essence. Essence dedicated her life to helping her sons achieve success and was devastated when she received the dreaded phone call no parent ever wants to hear. In the early morning of June 11, 2016 literally days before the much-anticipated draft, Essence received the tragic news from Adrian’s father. Her 20-year-old, ambitious, fun-loving and tenacious son, was shot and killed near the University of North Carolina, Charlotte campus. This tragedy had a shocking and paralyzing effect on the Bembry family. Knowing where to find support and assistance while planning a funeral service, dealing with unimaginable grief and the reality of life without a son, brother and best friend, were overwhelming for Essence and DeAndre’. This family tragedy served as the catalyst for DeAndre’ to develop a support system that could be an anchor and a resource hub for other families who may have to take a similar journey through grief. -

Beyond Classical

About the director, dean taba A highly regarded studio and freelance musician, Dean Taba began his musical studies on the piano at the age of 6 and played french horn in the Hawaii Youth Symphony. It was a desire to play in the high school jazz band that introduced him to the bass and improvised music. After extensive studies at the Berklee College of Music in Boston and a refinement of his skills on both the acoustic and electric bass, Dean relocated in 1984 to Los Angeles to HYS JAZZ become one of its most in demand musicians. Also a respected clinician and educator (Los Angeles Beyond Classical Music Academy, Musician’s Institute, Cal-Poly Pomona, Grove School of Music) Dean has recently performed/ recorded with Jeff Lorber, David Benoit, Mark Murphy, Jake Shimabukuo, Andy Summers, Sadao Watanabe, The San Francisco Symphony, Hiroshima, Rick Braun, The American Jazz Institute Orchestra, Dave Koz, Jeff Richman, Pauline Wilson, The Philippine Philharmonic Orchestra, Daniel Ho, Bill Watrous, and many others as well as playing on countless CDs, TV shows, and movie soundtracks. Take your passion and drive for music Learn more about HYS to the next level! HiYouthSymphony.org @HiYouthSymphony Hawaii Youth Symphony Open 1110 University Ave. #200 to all Honolulu, HI 96826-1598 (808) 941-9706 Students ages 14 - 18 (Grades 9 - 12) apply today! who play guitar, bass, While no prior jazz or improvisational experience is necessary, keyboards, piano, drums, admission to The Combo is by audition only. Up to 2 students sax, trumpet, trombone. of each instrument will be selected. -

Be a Friend of Moja

Najee October 7 The Gaillard Center 95 Calhoun Street Having collaborated with everyone in the music business from Prince and Quincy Jones to Stevie Wonder, Chaka Khan and Herbie Hancock, Najee’s technical agility, grace, compositional prowess, unbridled passion and fearless genre bending have made him one of the most sought after musicians of his generation. 2011MOJA Program Book_2004 MOJA Program Book 9/12/11 9:54 PM Page 2 City of Charleston South Carolina DEAR MOJADear MOJA FESTIVAL Festival Guests: GUESTS: Welcome to MOJA,Welcome Charleston’sto the 2011 MOJA annual Arts Festival, celebration Charleston’s annualof African-American celebration of African- and Carib- American and Caribbean Arts and Culture, produced by the City of Charleston Office of bean arts andCultural culture! Affairs. The 2016 MOJA Arts Festival assembles an amazing array of talents and traditions, affording locals and visitors alike the opportunity to celebrate This year’s festival highlights include: An Evening of Jazz Under the Stars with Najee at the cultural heritagePorter-Gaud and School artistic Stadium (pg.vitality 10); City of Gallery the Lowcountry.at Waterfront Park exhibitionProudly “Special produced by the Moments: Works From the Collection of Dr. Harold Rhodes, III” (pg. 27); A Classical City of CharlestonEncounter Office with Eleganza of atCultural the City GalleryAffairs at Waterfront in a longstanding Park followed by a champagnepartnership with the all-volunteer MOJAreception Arts(pg. 11); Festival Mt. Zion PlanningSpiritual Singers’ Committee, soul stirring Camp year Meeting after (pg. year 11); MOJA an brings enchanting evening of dance by PHILADANCO at the Gaillard Auditorium (pg. 7); Gwen Charleston togetherButler’s jazz as cruise we on gather the Charleston and Harborengage aboard in the festive Spirit of Charlestonperformances, (pg. -

Mediabase Chart

9/30/21, 2:07 PM Smooth Jazz 7-Day Report | Smooth Jazz Panel | Published Chart | Mediabase 24/7 Charts ... … You have 92 unread Net News stories. search by keyword ... Home > Mediabase > 7-Day Report > Smooth Jazz MediabaseMediabase Song Charts Adds Stations SONG CHARTS Report Panel Format 7-Day Report Smooth Jazz Smooth Jazz Currents/Recurrents C Get Report S O N G C H A R T S : 7 - D AY R E P O R T Smooth Jazz Smooth Jazz -- Published Chart -- Currents Only lw: Sep 12 - Sep 18 TW: Sep 19 - Sep 25 lw TW Artist Title TW lw Move Aud HOT 1 1 VINCENT INGALA On The Move 107 99 8 0.089 2 2 NICK COLIONNE Right Around The Corner 100 92 8 0.095 7 3 NILS Above The Clouds 88 83 5 0.074 9 4 BRIAN SIMPSON So Many Ways 84 80 4 0.091 6 5 RICHARD ELLIOT Right On Time 83 84 -1 0.082 3 6 ANDY SNITZER Non Stop 83 88 -5 0.09 13 7 ADAM HAWLEY Risin' Up 82 68 14 0.077 10 8 PAUL BROWN Deep Into It f/Rick Braun 81 77 4 0.092 5 9 RAGAN WHITESIDE Off The Cuff 81 85 -4 0.069 14 10 KAYLA WATERS Open Portals 79 67 12 0.058 4 11 PAUL HARDCASTLE Tropicool 79 85 -6 0.073 Industry Directory quickquick searchsearch 15 12 CHRISTIAN DE MESONES Hispanica f/Bob James 75 61 14 0.06 Industry Directory 12 13 JEFF LORBER FUSION Back Room 73 72 1 0.097 Name 11 14 BLAIR BRYANT B's Bounce 72 73 -1 0.081 8 15 DARREN RAHN Midnight Sun 71 81 -10 0.069 Company or Call Letters 17 16 JIMMY B. -

Annual AT&T San Jose Jazz Summer Fest Friday, August 12

***For Immediate Release*** 22nd Annual AT&T San Jose Jazz Summer Fest Friday, August 12 - Sunday, August 14, 2011 Plaza de Cesar Chavez Park, Downtown San Jose, CA Ticket Info: www.jazzfest.sanjosejazz.org Tickets: $15 - $20, Children Under 12 Free "The annual San Jose Jazz [Summer Fest] has grown to become one of the premier music events in this country. San Jose Jazz has also created many educational programs that have helped over 100,000 students to learn about music, and to become better musicians and better people." -Quincy Jones "Folks from all around the Bay Area flock to this giant block party… There's something ritualesque about the San Jose Jazz [Summer Fest.]" -Richard Scheinan, San Jose Mercury News "San Jose Jazz deserves a good deal of credit for spotting some of the region's most exciting artists long before they're headliners." -Andy Gilbert, San Jose Mercury News "Over 1,000 artists and 100,000 music lovers converge on San Jose for a weekend of jazz, funk, fusion, blues, salsa, Latin, R&B, electronica and many other forms of contemporary music." -KQED "…the festival continues to up the ante with the roster of about 80 performers that encompasses everything from marquee names to unique up and comers, and both national and local acts...." -Heather Zimmerman, Silicon Valley Community Newspapers San Jose, CA - June 15, 2011 - San Jose Jazz continues its rich tradition of presenting some of today's most distinguished artists and hottest jazz upstarts at the 22nd San Jose Jazz Summer Fest from Friday, August 12 through Sunday, August 14, 2011 at Plaza de Cesar Chavez Park in downtown San Jose, CA. -

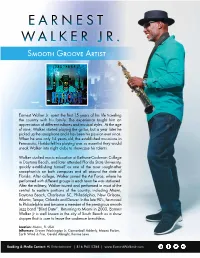

Earnest Walker Jr

EARNEST WALKER JR. Smooth Groove Artist Earnest Walker Jr. spent the first 15 years of his life traveling the country with his family. The experience taught him an appreciation of different cultures and musical styles. At the age of nine, Walker started playing the guitar, but a year later he picked up the saxophone and it has been his passion ever since. When he was only 14 years old, the established musicians in Pensacola, Florida felt his playing was so essential they would sneak Walker into night clubs to showcase his talents. Walker studied music education at Bethune-Cookman College in Daytona Beach, and later attended Florida State University, quickly establishing himself as one of the most sought-after saxophonists on both campuses and all around the state of Florida. After college, Walker joined the Air Force, where he performed with different groups in each town he was stationed. After the military, Walker toured and performed in most of the central to eastern portions of the country, including Miami, Daytona Beach, Charleston SC, Philadelphia, New Orleans, Atlanta, Tampa, Orlando and Denver. In the late 90’s, he moved to Philadelphia and became a member of the prestigious smooth jazz band “Blind Date”. Returning to Miami in 2003, Earnest Walker Jr is well known in the city of South Beach as a show stopper that is sure to leave the audience breathless. Location: Miami, FL USA Influences: Grover Washington Jr, Cannonball Adderly, Maceo Parker, Earth Wind & Fire, Gerald Albright, Ronnie Laws Booking & Media Contact: HJ Entertainment | 816.945.0288 | www.EarnestWalkerJr.com ON STAGE As solid, compelling and in the pocket as Walker is on disc, he’s best known in the jazz world as a powerhouse performer whose stage presence and creative style guarantees that every crowd is in an uproar. -

“I Want to Go to School, but I Can't”: Examining the Factors That Impact

―I Want to go to School, but I Can‘t‖: Examining the Factors that Impact the Anlo Ewe Girl Child‘s Formal Education in Abor, Ghana A dissertation presented to the faculty of The Gladys W. and David H. Patton College of Education and Human Services of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Karen Yawa Agbemabiese-Grooms August 2011 © 2011 Karen Yawa Agbemabiese-Grooms. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled ―I Want to go to School, but I Can‘t‖: Examining the Factors that Impact the Anlo Ewe Girl Child‘s Formal Education in Abor, Ghana by KAREN YAWA AGBEMABIESE-GROOMS has been approved for the Department of Educational Studies and The Gladys W. and David H. Patton College of Education and Human Services by Jaylynne N. Hutchinson Associate Professor of Educational Studies Renée A. Middleton Dean, The Gladys W. and David H. Patton College of Education and Human Services 3 Abstract AGBEMABIESE-GROOMS, KAREN YAWA, Ph.D., August 2011, Curriculum and Instruction, Cultural Studies ―I Want to go to School, but I Can‘t‖: Examining the Factors that Impact the Anlo Ewe Girl Child‘s Formal Education in Abor, Ghana (pp. 306) Director of Dissertation: Jaylynne N. Hutchinson This study explored factors that impact the Anlo Ewe girl child‘s formal educational outcomes. The issue of female and girl child education is a global concern even though its undesirable impact is more pronounced in African rural communities (Akyeampong, 2001; Nukunya, 2003). Although educational research in Ghana indicates that there are variables that limit girl‘s access to formal education, educational improvements are not consistent in remedying the gender inequities in education. -

Born in America, Jazz Can Be Seen As a Reflection of the Cultural Diversity and Individualism of This Country

1 www.onlineeducation.bharatsevaksamaj.net www.bssskillmission.in “Styles in Jazz Music”. In Section 1 of this course you will cover these topics: Introduction What Is Jazz? Appreciating Jazz Improvisation The Origins Of Jazz Topic : Introduction Topic Objective: At the end of this topic student would be able to: Discuss the Birth of Jazz Discuss the concept of Louis Armstrong Discuss the Expansion of Jazz Understand the concepts of Bebop Discuss todays Jazz Definition/Overview: The topic discusses that the style of music known as jazz is largely based on improvisation. It has evolved while balancing traditional forces with the pursuit of new ideas and approaches. Today jazz continues to expand at an exciting rate while following a similar path. Here you will find resources that shed light on the basics of one of the greatest musical developments in modern history.WWW.BSSVE.IN Born in America, jazz can be seen as a reflection of the cultural diversity and individualism of this country. At its core are openness to all influences, and personal expression through improvisation. Throughout its history, jazz has straddled the worlds of popular music and art music, and it has expanded to a point where its styles are so varied that one may sound completely unrelated to another. First performed in bars, jazz can now be heard in clubs, concert halls, universities, and large festivals all over the world. www.bsscommunitycollege.in www.bssnewgeneration.in www.bsslifeskillscollege.in 2 www.onlineeducation.bharatsevaksamaj.net www.bssskillmission.in Key Points: 1. The Birth of Jazz New Orleans, Louisiana around the turn of the 20th century was a melting pot of cultures. -

CASH BOX JAZZ ALBUMS Only Representatives of the Last 25 Years

— C-i 1 ON JAZZ \ CASH BOX JAZZ ALBUMS only representatives of the last 25 years in jazz, by the way) — is the place to go Title, Artist, Label, Number, Distributor for anybody who wants to learn about = Available on Compact Disc LB = Platinum (RIAA Certified) jazz, to hear how Louis Armstrong | W| ( = Gold (RIAA Certified) MANHATTAN BURN 23 V relates to Charlie Parker, how Char- El W PAQUITO D'RIVERA (Columbia FC lie Parker relates to Ornette Cole- L O 40583) 22 FULTON STREET MAUL etc. It is an indispensable W C man, TIM BERNE (Columbia FC 40530) NAJEE’S THEME * 2 19 collection and it is available from Smith- CLOUD ABOUT NAJEE (EMI ST 17241) El sonian Collection of Recordings, P.O. MERCURY* A CHANGE OF HEART * 1 11 DAVID TORN WITH MARK 1SHAM, DAVID SANBORN (Warner Bros. Box 23345, Washington, D.C. 20026. TONY LEVIN. BILL BRUFORD (ECM 27479-1) 831 108) SPARE CHANGE— I wrote a couple THE OTHER SIDE OF 18 EJ LADY FROM BRAZIL* MAXINE AND CO. - The late Maxine of weeks ago in this space about the ROUND MIDNIGHT TANIA MARIA (Manhattan ST 53045) at Holly- FEATURING DEXTER 25 GOOD MORNING KISS Sullivan was joined during a gig the new Bluebird and Novus reissues RCA GORDON * CARMEN LUNDY (Blackhawke BKH wood Roosevelt's Cinegrill earlier this year ai d issues, but I’d like to add a couple (Blue Note BT 85135) _ 523) 1 by fellow vocalists Diane Schuur (I) and Nellie A NICE PLACE TO BE 20 fzl REUNITED Dri of things. -

Omer Avital Ed Palermo René Urtreger Michael Brecker

JANUARY 2015—ISSUE 153 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM special feature BEST 2014OF ICP ORCHESTRA not clowning around OMER ED RENÉ MICHAEL AVITAL PALERMO URTREGER BRECKER Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 116 Pinehurst Avenue, Ste. J41 JANUARY 2015—ISSUE 153 New York, NY 10033 United States New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: [email protected] Interview : Omer Avital by brian charette Andrey Henkin: 6 [email protected] General Inquiries: Artist Feature : Ed Palermo 7 by ken dryden [email protected] Advertising: On The Cover : ICP Orchestra 8 by clifford allen [email protected] Editorial: [email protected] Encore : René Urtreger 10 by ken waxman Calendar: [email protected] Lest We Forget : Michael Brecker 10 by alex henderson VOXNews: [email protected] Letters to the Editor: LAbel Spotlight : Smoke Sessions 11 by marcia hillman [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by katie bull US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $35 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin or email [email protected] Festival Report Staff Writers 13 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, CD Reviews 14 Katie Bull, Tom Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Brad Farberman, Sean Fitzell, Special Feature: Best Of 2014 28 Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Miscellany Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, 43 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Robert Milburn, Russ Musto, Event Calendar 44 Sean J. O’Connell, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman As a society, we are obsessed with the notion of “Best”. -

Festival 2021

ARTS ACADEMY FESTIVAL 2 021 Interlochen Center for the Arts, a recipient of the National Medal of Arts, is a global arts organization that includes: • Interlochen Arts Academy - Arts boarding high school with Academy Fact Sheet rigorous college-prep academics • Interlochen Arts Camp - 59th Year | August 2020 - May 2021 Summer arts programs for grades 3-12 • College of Creative Arts - Lifelong learning in the arts Total Enrollment Classes • Interlochen Public Radio - 545 Students Freshman 50 Two stations: Classical Music and News (NPR Member Station) Sophomore 95 46 U.S. states and territories Junior 165 • Interlochen Presents - presenting more than 600 events annaully represented Senior 213 featuring students, faculty, and Post-graduate 22 internationally recognized guest artists. Top state delegations: • Interlochen Online - a virtual State Students Residential Status platform that brings the world- Michigan 104 Boarding 503 renowned Interlochen experience Day Students 42 into your home, building a virtual California 32 bridge of connection to the world’s New York 26 leading arts educators. Arts Areas Florida 25 Creative Writing 25 Interlochen Arts Academy challenges Illinois 23 Dance 41 students to achieve artistically and Texas 19 Film & New Media 22 academically. Since 1980, 46 Arts Wisconsin 18 Interdisciplinary Arts 24 Academy students have been named Presidential Scholars, unmatched Ohio 17 Music 269 by any other high school in the country. Maryland 16 Theatre 109 Indiana 14 Visual Arts 55 Academy students create hundreds of presentations including student concerts, performances, exhibits, readings, and screenings. 20 countries and territories More than 300 faculty and staff work to maintain a positive and safe Angola 1 Korea 6 environment for all students. -

The BG News November 23, 1993

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 11-23-1993 The BG News November 23, 1993 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News November 23, 1993" (1993). BG News (Student Newspaper). 5617. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/5617 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. 4? The BG News Tuesday , November 23, 1993 Bowling Green, Ohio Volume 76, Issue 64 Briefs Handgun bill center of debate Weather The Associated Press clean up the savings and loan fi- baum, D-Ohio. over unanimous Republican op- an ambitious final-day agenda asco. President Clinton prodded position, and last week's approv- that ranged from the campaign lawmakers to deliver the bill for Sunny skies coming: The House approved a plan to al of the North American Free overhaul bill to a $90 billion WASHINGTON - After a year remake the campaign finance his signature as a "Thanksgiving Trade Agreement. package of spending cuts to less marked by swings from confron- laws, a key item on President Day present" to a crime-weary Today, partly sunny. High Rep. Bob Livingston, R-La, weighty concerns. Among them tation to cooperation, Congress Clinton's agenda. The 255-175 public.