Introducing Nkami: a Forgotten Guang Language and People of Ghana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Party Organisation and Women's Empowerment

Final report Political party organisation and women’s empowerment A field experiment in Ghana Nahomi Ichino Noah L. Nathan December 2017 When citing this paper, please use the title and the following reference number: S-33403-GHA-1 Political Party Organization and Women's Empowerment: A Field Experiment in Ghana∗ Nahomi Ichinoyand Noah L. Nathanz December 31, 2017 Gender gaps in participation and representation are common in new democracies, both at the elite level and at the grassroots. We investigate efforts to close the grassroots gender gap in rural Ghana, a patronage-based democracy in which a dense network of political party branches provides the main avenue for local participation. We report results from a randomized field experiment to address norms against women's participation and encourage women's participa- tion ahead of Ghana's December 2016 elections. The treatment is a large community meeting presided over by the traditional chief, known locally as a durbar. We find null results. The treat- ment was hampered in part by its incomplete implementation, including by local political party leaders who may have feared an electorally-risky association with a controversial social message. The study emphasizes the importance of social norms in explaining gender gaps in grassroots politics in new democracies and contributes new evidence on the limitations of common civic education interventions used in the developing world. ∗Special tanks to Johnson Opoku, Samuel Asare Akuamoah, and the staff of the National Commission of Civic Education (NCCE) for their partnership, as well as to Santiago S´anchez Guiu, Helen Habib and IPA-Ghana. -

Small and Medium Forest Enterprises in Ghana

Small and Medium Forest Enterprises in Ghana Small and medium forest enterprises (SMFEs) serve as the main or additional source of income for more than three million Ghanaians and can be broadly categorised into wood forest products, non-wood forest products and forest services. Many of these SMFEs are informal, untaxed and largely invisible within state forest planning and management. Pressure on the forest resource within Ghana is growing, due to both domestic and international demand for forest products and services. The need to improve the sustainability and livelihood contribution of SMFEs has become a policy priority, both in the search for a legal timber export trade within the Voluntary Small and Medium Partnership Agreement (VPA) linked to the European Union Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (EU FLEGT) Action Plan, and in the quest to develop a national Forest Enterprises strategy for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD). This sourcebook aims to shed new light on the multiple SMFE sub-sectors that in Ghana operate within Ghana and the challenges they face. Chapter one presents some characteristics of SMFEs in Ghana. Chapter two presents information on what goes into establishing a small business and the obligations for small businesses and Ghana Government’s initiatives on small enterprises. Chapter three presents profiles of the key SMFE subsectors in Ghana including: akpeteshie (local gin), bamboo and rattan household goods, black pepper, bushmeat, chainsaw lumber, charcoal, chewsticks, cola, community-based ecotourism, essential oils, ginger, honey, medicinal products, mortar and pestles, mushrooms, shea butter, snails, tertiary wood processing and wood carving. -

KWAHU CULTURAL VALUES-CONTENTS.Pdf

Kwahu Cultural Values: Their Impact On The People’s Art BY Emmanuel Yaw Adonteng (BE.D. IN ART) A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in African Art And Culture on July, 2009. July, 2009 © 2009 Department of General Art Studies DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work towards the MA (African Art and Culture) and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no materials previously published by another person nor material which has been accepted for the i award of any other degree of the University except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text EMMANUEL YAW ADONTENG ( 20045462) ………………………………………….…….. ……………… ………… Student Name & ID Signature Date Certified by: DR. O. OSEI AGYEMANG ………………………………………….. ……………… ………… Supervisor‟s Name Signature Date Certified by: DR. JOE ADU-AGYEM ………………………………………….. ……………… ………… Head of Dept Name Signature Date ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I express my gratitude to God Almighty for the love, kindness and protection accorded me and also enabling me to write this thesis. I also want to extend my heartfelt gratitude and appreciation to those who extended the love ii and support needed most in making this thesis a reality. I also register my sincere thanks to the authors whose books and articles I cited as sources of references. My utmost thanks go to Dr Opamshen Osei Agyeman, my supervisor and a lecturer of the college of Art, KNUST, KUMASI for his assistance, guidance and encouragement. I am grateful to Dr Ben K. -

Name Phone Number Location Certification Class 1 Abayah Joseph Tetteh 0244814202 Somanya, Krobo,Eastern Region Domestic 2 Abdall

NAME PHONE NUMBER LOCATION CERTIFICATION CLASS 1 ABAYAH JOSEPH TETTEH 0244814202 SOMANYA, KROBO,EASTERN REGION DOMESTIC 2 ABDALLAH MOHAMMED 0246837670 KANTUDU, EASTERN REGION DOMESTIC 3 ABLORH SOWAH EMMANUEL 0209114424 AKIM-ODA, EASTERN COMMERCIAL 4 ABOAGYE ‘DANKWA BENJAMIN 0243045450 AKUAPIM DOMESTIC 5 ABURAM JEHOSAPHAT 0540594543 AKIM AYIREDI,EASTERN REGION DOMESTIC 6 ACHEAMPONG BISMARK 0266814518 SORODAE, EASTERN REGION DOMESTIC 7 ACHEAMPONG ERNEST 0209294941 KOFORIDUA, EASTERN REGION COMMERCIAL 8 ACHEAMPONG ERNEST KWABENA 0208589610 KOFORIDUA, EASTERN REGION DOMESTIC 9 ACHEAMPONG KOFI 0208321461 AKIM ODA,EASTERN REGION DOMESTIC 10 ACHEAMPONG OFORI CHARLES 0247578581 OYOKO,KOFORIDUA, EASTERN REGIO COMMERCIAL 11 ADAMS LUKEMAN 0243005800 KWAHDESCO BUS STOP DOMESTIC 12 ADAMU FRANCIS 0207423555 ADOAGYIRI-NKAWKAW, EASTERN REG DOMESTIC 13 ADANE PETER 0546664481 KOFORIDUA,EASTERN REGION DOMESTIC 14 ADDO-TETEBO KWAME 0208166017 SODIE, KOFORIDUA INDUSTRIAL 15 ADJEI SAMUEL OFORI 0243872431/0204425237 KOFORIDUA COMMERCIAL 16 ADONGO ROBERT ATOA 0244525155/0209209330 AKIM ODA COMMERCIAL 17 ADONGO ROBERT ATOA 0244525155 AKIM,ODA,EASTERN REGIONS INDUSTRIAL 18 ADRI WINFRED KWABLA 0246638316 AKOSOMBO COMMERCIAL 19 ADU BROBBEY 0202017110 AKOSOMBO,E/R DOMESTIC 20 ADU HENAKU WILLIAM KOFORIDUA DOMESTIC 21 ADUAMAH SAMPSON ODAME 0246343753 SUHUM, EASTERN REGION DOMESTIC 22 ADU-GYAMFI FREDERICK 0243247891/0207752885 AKIM ODA COMMERCIAL 23 AFFUL ABEDNEGO 0245805682 ODA AYIREBI COMMERCIAL 24 AFFUL KWABENA RICHARD 0242634300 MARKET NKWATIA DOMESTIC 25 AFFUL -

A Strategic Study on Foreign Fund Utilization in Chinese Insurance

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lancaster E-Prints Mathematical Theory and Modeling www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-5804 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0522 (Online) Vol.5, No.8, 2015 Data Based Mechanistic modelling optimal utilisation of raingauge data for rainfall-riverflow modelling of sparsely gauged tropical basin in Ghana *Boateng Ampadu1, Nick A. Chappell2, Wlodek Tych2 1. University for Development Studies, Faculty of Applied Sciences, Department of Earth and Environmental Science, P. O. Box 24, Navrongo-Ghana 2. Lancaster Environment Centre, Lancaster University, Lancaster, LA1 4YQ, UK * Corresponding author E-mail address: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Data-Based Mechanistic (DBM) modelling is a Transfer Function (TF) modelling approach, whereby the data defines the model. The DBM approach, unlike physics-based distributed and conceptual models that fit existing laws to data-series, uses the data to identify the model structure in an objective statistical manner. The approach is parsimonious, in that it requires few spatially-distributed data and is, therefore, suitable for data limited regions like West Africa. Multiple Input Single Output (MISO) rainfall to riverflow modelling approach is the utilization of multiple rainfall time-series as separate input in parallel into a model to simulate a single riverflow time-series in a large scale. The approach is capable of simulating the effects of each rain gauge on a lumped riverflow response. Within this paper we present the application of DBM-MISO modelling approach to 20778 km2 humid tropical rain forest basin in Ghana. The approach makes use of the Bedford Ouse modelling technique to evaluate the non-linear behaviour of the catchment with the input of the model integrated in different ways including into new single-input time-series for subsequent Single Input Single Output (SISO) modelling. -

Crime Statistics

ANNUAL CRIME STATISTICS (2016) SOURCE: STATISTICS & INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY UNIT (SITU), CID HEADQUARTERS, ACCRA. Page 1 ANNUAL CRIME STATISTICS 2016 CRIME STATISTICS Comparative analysis of Crime Statistics for the year 2015 and 2016 showed remarkable results: Police received a total of 177,241 complaints throughout the country in the year 2016. This represents a decrease of 9,193 cases, which translated into 4.9% over that of the year 2015 which recorded a figure of 186,434. Out of this total, 166,839 representing 94.1% were registered as true cases; the remaining 10,402 cases representing 5.9% were refused. The cases, which were refused, were regarded as trivial, civil in nature or false and so did not warrant Police action. Out of the true cases, 29,778 cases were sent to court for prosecution. At the court, 8,379 cases representing 28.1% gained conviction whilst 812 representing 2.7% were acquitted. At the close of the year 2016, 20,587 cases representing 69.1% of the total number of cases sent to court for prosecutions were awaiting trial. A total of 36,042 cases were closed as undetected whilst 101,019 cases representing 60.5% of the total number of true cases were under investigation at the close of the year 2016. CRIME REVIEW Figures on the total number of cases reported to the Police throughout the country and their treatments are given as follows: SOURCE: STATISTICS & INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY UNIT (SITU), CID HEADQUARTERS, ACCRA. Page 2 TOTAL NUMBER OF CASES REPORTED 177,241 Total number of cases refused 10,402 Total number of -

Kwahu West Municipal Assembly

REPUBLIC OF GHANA THE COMPOSITE BUDGET OF THE KWAHU WEST MUNICIPAL ASSEMBLY FOR THE 2016 FISCAL YEAR pg. 1 Contents APPROVAL OF 2016 COMPOSITE BUDGET ESTIMATES ............................................... 4 THE NARRATIVE STATEMENT ........................................................................................... 5 1.0 THE MUNICIPALITY .................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 5 Location and Size ............................................................................................................... 5 Population .......................................................................................................................... 5 The Economy ......................................................................................................................... 6 Business, Trade and Manufacturing .................................................................................. 6 Agriculture ......................................................................................................................... 6 Tourism and Mining .......................................................................................................... 6 Economic Potentials of the Municipality ........................................................................... 7 Markets ............................................................................................................................. -

Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African Languages

Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African Languages UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African Languages Gerrit J. Dimmendaal University of Cologne John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American 8 National Standard for Information Sciences — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dimmendaal, Gerrit Jan. Historical linguistics and the comparative study of African languages / Gerrit J. Dimmendaal. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. African languages--Grammar, Comparative. 2. Historical linguistics. I. Title. PL8008.D56 2011 496--dc22 2011002759 isbn 978 90 272 1178 1 (Hb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 1179 8 (Pb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 8722 9 (Eb) © 2011 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. John Benjamins Publishing Company • P.O. Box 36224 • 1020 me Amsterdam • The Netherlands John Benjamins North America • P.O. Box 27519 • Philadelphia PA 19118-0519 • USA UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs Table of contents Preface ix Figures xiii Maps xv Tables -

Works of Russell G. Schuh

UCLA Works of Russell G. Schuh Title Schuhschrift: Papers in Honor of Russell Schuh Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7c42d7th ISBN 978-1-7338701-1-5 Publication Date 2019-09-05 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7c42d7th#supplemental Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Schuhschrift Margit Bowler, Philip T. Duncan, Travis Major, & Harold Torrence Schuhschrift Papers in Honor of Russell Schuh eScholarship Publishing, University of California Margit Bowler, Philip T. Duncan, Travis Major, & Harold Torrence (eds.). 2019. Schuhschrift: Papers in Honor of Russell Schuh. eScholarship Publishing. Copyright ©2019 the authors This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Interna- tional License. To view a copy of this license, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. ISBN: 978-1-7338701-1-5 (Digital) 978-1-7338701-0-8 (Paperback) Cover design: Allegra Baxter Typesetting: Andrew McKenzie, Zhongshi Xu, Meng Yang, Z. L. Zhou, & the editors Fonts: Gill Sans, Cardo Typesetting software: LATEX Published in the United States by eScholarship Publishing, University of California Contents Preface ix Harold Torrence 1 Reason questions in Ewe 1 Leston Chandler Buell 1.1 Introduction . 1 1.2 A morphological asymmetry . 2 1.3 Direct insertion of núkàtà in the left periphery . 6 1.3.1 Negation . 8 1.3.2 VP nominalization fronting . 10 1.4 Higher than focus . 12 1.5 Conclusion . 13 2 A case for “slow linguistics” 15 Bernard Caron 2.1 Introduction . -

ED373534.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 373 534 FL 022 094 AUTHOR Bodomo, Adams B. TITLE Complex Predicates and Event Structure: An Integrated Analysis of Serial Verb Constructions in the Mabia Languages of West Africa. Working Papers in Linguistics No. 20. INSTITUTION Trondheim Univ. (Norway). Dept. of Linguistics. REPORT NO ISSN-0802-3956 PUB DATE 93 NOTE 148p.; Thesis, University of Trondheim, Norway. Map on page 110 may not reproduce well. PUB TYPE Dissertations/Theses Undetermined (040) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *African Languages; Foreign Countries; *Grammar; *Language Patterns; Language Research; Language Variation; *Semantics; Structural Analysis (Linguistics); *Syntax; Uncommonly Taught Languages; *Verbs IDENTIFIERS Africa (West); Dagari ABSTRACT An integrated analysis of the syntax and semantics of serial verb constructions (SVCs) in a group of West African languages is presented. With data from Dagadre and closest relatives, a structural definition for SVCs is developed (two or more lexical verbs that share grammatical categories within a clause), establishing SVCs as complex predicates. Based on syntactic theories, a formal phrase structure is adapted forrepresentation of SVCs, interpreting each as a product of a series of VP adjunctions. Within this new, non-derivational, pro-expansionary approach to grammar, several principles are developed to license grammatical information flow and verbal ordering priority. Based on semantic theories, a functional account of SVCs is developed: that the actions represented by the verbs in the SVC together express a single, complex event. A new model of e. -ant structure for allconstructional transitions is proposed, and it is illustrated how two types of these transitions, West African SVCs and Scandinavian small clause constructions(SCCs), conform to this proposed event structure. -

Projected Changes in the Amplitude of Future El Niño Type of Events

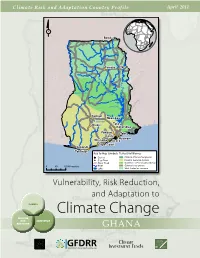

Climate Risk and Adaptation Country Profile April 2011 N Bawku !( Yendi !(Tamale !( Banda Nwanta Lake Volta !(Kumasi !(Nkawkaw Bosumtwi Tafo !( Obuasi !( !( Koforidua Pokoasi !( Tema !( !( Teshi !( .! Nsawam Winneba !( Accra !(Cape Coast Sekondi !(!( Takoradi Key to Map Symbols Terrestrial Biomes Capital Central African mangroves City/Town Eastern Guinean forests Major Road Guinean forest-savanna mosaic 0 60 120 Kilometers River Guinean mangroves Lake West Sudanian savanna Vulnerability, Risk Reduction, and Adaptation to CLIMATE Climate Change DISASTER RISK ADAPTATION REDUCTION GHANA Climate Climate Change Team Investment Funds ENV Climate Risk and Adaptation Country Profile Ghana Climate Risk and Adaptation Country Profile COUNTRY OVERVIEW Ghana is located in West Africa and shares borders with Togo on the east, Burkina Faso to the north, La Cote D’Ivoire on the west and the Gulf of Guinea to the south. Ghana covers an area of 238,500 km2. The country is relatively well endowed with water: extensive water bodies, including Lake Volta and Bosomtwi, occupy 3,275 km2, while seasonal and perennial rivers occupy another 23,350 square kilometers. Ghana's population is about 23.8 million (2009)1 and is estimated to be increasing at a rate of 2.1% per annum. Life expectancy is 56 years and infant mortality rate is 69 per thousand life births. Ghana is classified as a developing country with a per capita income of US$ 1098 (2009). Agriculture and livestock constitute the mainstay of Ghana’s economy, accounting for 32% of GDP in 2009 and employing 55% of the economically active population2. Agriculture is predominantly rainfed, which exposes it to the effects of present climate variability and the risks of future climate change. -

Ministry of Health

REPUBLIC OF GHANA MEDIUM TERM EXPENDITURE FRAMEWORK (MTEF) FOR 2021-2024 MINISTRY OF HEALTH PROGRAMME BASED BUDGET ESTIMATES For 2021 Transforming Ghana Beyond Aid REPUBLIC OF GHANA Finance Drive, Ministries-Accra Digital Address: GA - 144-2024 MB40, Accra - Ghana +233 302-747-197 [email protected] mofep.gov.gh Stay Safe: Protect yourself and others © 2021. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be stored in a retrieval system or Observe the COVID-19 Health and Safety Protocols transmitted in any or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the Ministry of Finance Get Vaccinated MINISTRY OF HEALTH 2021 BUDGET ESTIMATES The MoH MTEF PBB for 2021 is also available on the internet at: www.mofep.gov.gh ii | 2021 BUDGET ESTIMATES Contents PART A: STRATEGIC OVERVIEW OF THE MINISTRY OF HEALTH ................................ 2 1. NATIONAL MEDIUM TERM POLICY OBJECTIVES ..................................................... 2 2. GOAL ............................................................................................................................ 2 3. VISION .......................................................................................................................... 2 4. MISSION........................................................................................................................ 2 5. CORE FUNCTIONS ........................................................................................................ 2 6. POLICY OUTCOME