University of Education, Winneba College Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice | RSACVP 2017 | 6-9 April 2017 | Suceava – Romania Rethinking Social Action

Available online at: http://lumenpublishing.com/proceedings/published-volumes/lumen- proceedings/rsacvp2017/ 8th LUMEN International Scientific Conference Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice | RSACVP 2017 | 6-9 April 2017 | Suceava – Romania Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice The Convertor Status of Article of Case and Number in the Romanian Language Diana-Maria ROMAN* https://doi.org/10.18662/lumproc.rsacvp2017.62 How to cite: Roman, D.-M. (2017). The Convertor Status of Article of Case and Number in the Romanian Language. In C. Ignatescu, A. Sandu, & T. Ciulei (eds.), Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice (pp.682-694). Suceava, Romania: LUMEN Proceedings https://doi.org/10.18662/lumproc.rsacvp2017.62 © The Authors, LUMEN Conference Center & LUMEN Proceedings. Selection and peer-review under responsibility of the Organizing Committee of the conference 8th LUMEN International Scientific Conference Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice | RSACVP 2017 | 6-9 April 2017 | Suceava – Romania The Convertor Status of Article of Case and Number in the Romanian Language Diana-Maria ROMAN1* Abstract This study is the outcome of research on the grammar of the contemporary Romanian language. It proposes a discussion of the marked nominalization of adjectives in Romanian, the analysis being focused on the hypostases of the convertor (nominalizer). Within this area of research, contemporary scholarly treaties have so far accepted solely nominalizers of the determinative article type (definite and indefinite) and nominalizers of the vocative desinence type, in the singular. However, with regard to the marked conversion of an adjective to the large class of nouns, the phenomenon of enclitic articulation does not always also entail the individualization of the nominalized adjective, as an expression of the category of definite determination. -

Possessive Agreement Turned Into a Derivational Suffix Katalin É. Kiss 1

Possessive agreement turned into a derivational suffix Katalin É. Kiss 1. Introduction The prototypical case of grammaticalization is a process in the course of which a lexical word loses its descriptive content and becomes a grammatical marker. This paper discusses a more complex type of grammaticalization, in the course of which an agreement suffix marking the presence of a phonologically null pronominal possessor is reanalyzed as a derivational suffix marking specificity, whereby the pro cross-referenced by it is lost. The phenomenon in question is known from various Uralic languages, where possessive agreement appears to have assumed a determiner-like function. It has recently been a much discussed question how the possessive and non-possessive uses of the agreement suffixes relate to each other (Nikolaeva 2003); whether Uralic definiteness-marking possessive agreement has been grammaticalized into a definite determiner (Gerland 2014), or it has preserved its original possessive function, merely the possessor–possessum relation is looser in Uralic than in the Indo-Europen languages, encompassing all kinds of associative relations (Fraurud 2001). The hypothesis has also been raised that in the Uralic languages, possessive agreement plays a role in organizing discourse, i.e., in linking participants into a topic chain (Janda 2015). This paper helps to clarify these issues by reconstructing the grammaticalization of possessive agreement into a partitivity marker in Hungarian, the language with the longest documented history in the Uralic family. Hungarian has two possessive morphemes functioning as a partitivity marker: -ik, an obsolete allomorph of the 3rd person plural possessive suffix, and -(j)A, the productive 3rd person singular possessive suffix. -

Colours in Chumburung, Metaphoric Uses and Ideophones Are Also Investigated

RED IS A VERB: THE GRAMMAR OF COLOUR IN CHUMBURUNG Gillian F. Hansford Ghana Institute of Linguistics, Literacy and Bible Translation [email protected] Chumburung of Ghana was one of the languages included in Berlin and Kay’s seminal World Colour Survey. Their conclusion was that Chumburung had five and a half so called basic colour terms. This present paper looks specifically at the grammar of those colour terms, which was not one of the aspects recorded at the time. An alternative approach is suggested to that of colour per se. The secondary colours are also investigated, and it is shown how the division is made clear by the grammar. In an attempt to clarify what are the most basic colours in Chumburung, metaphoric uses and ideophones are also investigated. A brief look is taken at other languages of Ghana in an attempt at historical “reconstruction”. This research concludes that the WCS analysis of Chumburung needs to be corrected. Le Chumburung du Ghana est une des langues citées dans l’œuvre séminale de Berlin et Kay relative aux Termes des Couleurs dans le Monde. Selon cette étude, il y a cinq et demi de termes de base des couleurs en Chumburung. Le présent article met en exergue de manière spécifique la grammaire de ces termes de couleur, un aspect qui était resté occulté lors de l’enquête à ce sujet. Je propose une démarche alternative qui ne se limite pas aux seules couleurs. J’explore également les couleurs secondaires et je démontre comment la division est rendue plus claire par la grammaire. -

Country: Ghana Language: D G (Mo) Description: Bible 1St Edition

Country: Ghana Language: D g (Mo) Description: Bible 1st edition Speakers: 55,000 Translators: Noah Ampem, Gabriel Chiu, Stephen Kofi Mensah, Began: 1981 Wilfred Opoku, Edward Banchagla, Joshua Osei Translation Consultant: Marjorie Crouch Published: 2015 Literacy Specialist: Patricia Herbert Editorial Consultant: Margaret Langdon Dedication: March 2016 Naa Dr Tebala kala Gyasehene thanking God for the Deg Bible Most Dega people live in Dega Hare (Dega land) which The people call themselves, Dega, meaning “multiply- is located in the Bole district in the Northern Region ing”, “spreading quickly”, or “fertility”. One person is and the Wenchi and Kintampo districts in the Brong called a Deg and the language is also known as Deg. Ahafo Region. Dega Hare consists of about 46 villag- Other ethnic groups in Ghana call the Dega, Mo, “the es in an area roughly 650 square miles (about the size people who did well”. It’s believed that this name, Mo, of Union County in North Carolina). Outside Dega acknowledges an event where the Dega came to the aid Hare, there are a number of Dega people in the Jaman of another Ghanaian tribe in battle, who would have District in Ghana. A group also lives in several villages been defeated without the valiant efforts of the Dega. in Cote d’lvoire and Dega in Ghana call those people Lamoolatina (the people beyond the river). [continued] Even before Christianity or Islam came to Dega weak and impure human beings in need of a power Hare, Dega acknowledged the existence of God, the not their own to know Him… it seemed, this God, Supreme Being. -

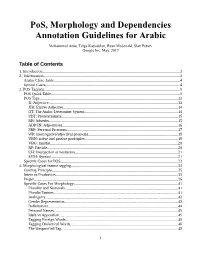

Pos, Morphology and Dependencies Annotation Guidelines for Arabic

PoS, Morphology and Dependencies Annotation Guidelines for Arabic Mohammed Attia, Tolga Kayadelen, Ryan Mcdonald, Slav Petrov Google Inc. May, 2017 Table of Contents 1. Introduction............................................................................................................................................2 2. Tokenization...........................................................................................................................................3 Arabic Clitic Table................................................................................................................................4 Special Cases.........................................................................................................................................4 3. POS Tagging..........................................................................................................................................8 POS Quick Table...................................................................................................................................8 POS Tags.............................................................................................................................................13 JJ: Adjective....................................................................................................................................13 JJR: Elative Adjective.....................................................................................................................14 DT: The Arabic Determiner System...............................................................................................14 -

Thiel-Katalog-Ghana.Pdf

= GHANA PASTELLE 2012/13 ANTON THIEL ANTON THIEL Bergheimerstraße 41, 5020 Salzburg, AUSTRIA www.antonthiel.at • [email protected] • 0699 12165281 1974–79 Studium an der Akademie der Bildenden Künste (Prof. Max Weiler), Studium der Germanistik an der Universität Wien 1980–88 Lehrbeauftragter für Schrift und Schriftgestaltung sowie Fachdidaktik an der Hochschule Mozarteum in Salzburg seit 1980 Lehrer am Musischen Gymnasium, Salzburg 1987–1996 Arbeit an der Serie „America, America“, Pastellkreiden 1997 „Erich Schuhputzer – eine architektonische Studie“, Videofilm zum Salzburger Weltkulturerbefest zusammen mit Robert Wintersteiger 2005–2006 Aufenthalt in Marokko und Kuba 2006 Beginn der Aquarellserie: „Mythen und Verschlungenes“ seit 2006 Aktionen und Installationen mit dem „fahrbaren Haus“, Salzburger Architekturpreis 2010 2012 Aufenthalt in Ghana; Beginn der Serie GHANA, Pastellkreiden VÖLKER & ETHNIEN GHANAS: A Ada, Adangbe (Dangbe, Adantonwi, Agotime, Adan), Adele (Gidire, Bidire), Agni (Anyin, Anyi), Ahafo, Ahanta (Anta,) Akan, Akwamu, (Aquambo), Akwapim (Akuapem, Akwapem, Twi, Akuapim, Aquapim, Akwapi), Akim (Akyem), Ak- pafu (Siwu, Akpafu-Lolobi, Lolobi-Akpafu, Lolobi, Siwusi), Akposo (Kposo), Animere (Anyimere, Kunda), Anufo (Chokosi, Chakosi, Kyokosi, Tchokossi, Tiokossi), Anum (Gua, Gwa, Anum-Boso), Aschanti (Aschanti), Apollo (Nzema), Assin (Asen), Avatime (Sia, Sideme, Afatime), Awutu (Senya); B Bassari (Ghana), Be-Tyambe Banafo (Banda, Dzama, Nafana, Senufo), Bimoba (Moba, Moar, Moor), Birifor (Ghana Birifor, Birifor Süd), Bissa -

5 Adjectives and Adverbs

5 ADJECTIVES AND ADVERBS 1 Choose the correct alternative in the sentences below. If you find both alternatives acceptable, explain any difference in meaning. a. All the venues are easy/easily accessible. b. There’s a possible/possibly financial problem. c. We admired the wonderful/wonderfully panorama. d. Our neighbours are (simple)/simply people who live near us. Although less likely in this case, the adjective “simple” could be used as a premodifier to describe the noun (that is, the neighbours are not sophisticated people). Since the sentence seems to be a more general description of neighbours, however, the adverb “simply” is the more likely choice. The adverb serves as a comment on the part of the speaker. e. They seemed happy/happily about George’s victory. f. Similar/Similarly teams of medical advisers were called upon. g. Something in here smells horrible/horribly. Normally an adjective will follow a linking verb to describe a quality of the subject ref- erent. However, the adverb “horribly” can be used to refer to the intensity of the smell. h. This cream will give you a beautiful/beautifully smooth complexion. i. Particular/Particularly groups such as recent immigrants felt their needs were being overlooked. INTRODUCING ENGLISH GRAMMAR, THIRD EDITION KEY TO EXERCISES 5 Adjectives and Adverbs The adjective “particular” premodifies or describes the noun “groups”, whereas the use of the adverb “particularly” functions as a comment on the part of the speaker. 2 Explain the difference in form and meaning between the members of each pair. a. 1 She is a natural blonde. -

Adjective Attribution (Studies in Diversity Linguistics 2)

Michael Rießler. 2016. Adjective attribution (Studies in Diversity Linguistics 2). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog © 2016, Michael Rießler Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 978-3-944675-65-7 (Digital) 978-3-944675-66-4 (Hardcover) 978-3-944675-49-7 (Softcover) 978-1-530889-34-1 (Softcover US) ISSN: 2363-5568 Cover and concept of design: Ulrike Harbort Typesetting: Felix Kopecky, Sebastian Nordhoff, Michael Rießler Proofreading: Martin Haspelmath, Joshua Wilbur Fonts: Linux Libertine, Arimo, DejaVu Sans Mono Typesetting software:Ǝ X LATEX Language Science Press Habelschwerdter Allee 45 14195 Berlin, Germany langsci-press.org Storage and cataloguing done by FU Berlin Language Science Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. За най-любимите ми Алма, Ива и Кристина Contents Preface This is a thoroughly revised version of my doctoral dissertation Typology and evolution of adjective attribution marking in the languages of northern Eurasia, which I defended at Leipzig University in January 2011 and published electroni- cally as riesler2011a I am indebted to my family members, friends, project collab- orators, data consultants, listeners, supporters, sources of inspiration, opponents and other people who assisted in completing my dissertation. I am very thankful to the series editors who accepted my manuscript for pub- lication with this prestigious open-access publisher, to the technical staff at Lan- guage Science Press, as well as to proofreaders and other individuals who have spent their valuable time producing of this book. -

Syntactic Classes of the Arabic Active Participle and Their Equivalents in Translation: a Comparative Study in Two English Quranic Translations

Syntactic Classes of the Arabic Active Participle and their Equivalents in Translation: A Comparative Study in Two English Quranic Translations Hassan A. H. Gadalla, Ph.D. in Linguistics, Assiut University, Egypt [Published in the Bulletin of the Faculty of Arts, Assiut University, Egypt. Vol. 18, Jan. 2005, pp. 1-37.] 0. Introduction: This study attempts to provide an analysis of the syntactic classes of Arabic active participle forms and discuss their translations based on a comparative study of two English Quranic translations by Ali (1934) and Pickthall (1930). It starts with a brief introduction to the active participle in Arabic and the Arab grammarians' discussion of its syntactic classes. Then, it explains the study aim and technique. The third section presents an analysis of the results of the study by discussing the various renderings of the Arabic active participle in the two English translations of the Quran. For the phonemic symbols used to transcribe Arabic data, see Appendix (1) and for the symbols and abbreviations employed in the study, see Appendix (2). 1 1. Syntactic Classes of the Arabic Active Participle: The active participle (AP) is a morphological form derived from a verb to refer to the person or animate being that performs the action denoted by the verb. In Classical and Modern Standard Arabic grammars, it is called /?ism-u l-faa9il/ 'noun of the agent' and it has two patterns; one formed from the primary triradical verb and the other from the derived triradical as well as the quadriradical verbs. The former has the form [Faa9iL], e.g. -

Dagbani-English Dictionary

DAGBANI-ENGLISH DICTIONARY with contributions by: Harold Blair Tamakloe Harold Lehmann Lee Shin Chul André Wilson Maurice Pageault Knut Olawski Tony Naden Roger Blench CIRCULATION DRAFT ONLY ALL COMENTS AND CORRECTIONS WELCOME This version prepared by; Roger Blench 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/Answerphone/Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 E-mail [email protected] http://homepage.ntlworld.com/roger_blench/RBOP.htm This printout: Tamale 25 December, 2004 1. Introduction...................................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Transcription.................................................................................................................................................... 5 Vowels ................................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Consonants......................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Tones .................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Plurals and other forms.................................................................................................................................................... 8 Variability in Dagbani -

Ani 'Eye' Metaphorical Expressions in Akan

ANI ‘EYE’ METAPHORICAL EXPRESSIONS IN AKAN Ani anhunu a ny tan, ‘If the eyes do not see it, it is not nasty.’ Kofi Agyekum Department of Linguistics, University of Ghana Legon [email protected] The paper addresses the semantic shifts, extensions and metaphorical use of ani ‘eyes’ in Akan (a Ghanaian language). It focuses attention on the semantic patterns and pragmatic nature of ani based metaphors and their usage in a variety of contexts. In Akan, the body part expressions have extended meanings that still have some relationship with the original words. The body parts thus act as the productive lexical items for the semantic and metaphoric derivation. I will consider the body part ani from its physical and cognitive representations. The paper also looks at the positive and negative domains of ani ‘eye’ expressions. The data are taken from Akan literature books, the Akan Bible and recorded materials from radio discussions. The paper illustrates that there is a strong relation between people’s conceptual, environmental and cultural experiences and their linguistic systems. Cet article met en exergue les changements sémantiques, les extensions et l’emploi métaphorique de ani ‘yeux’ en akan, (une langue du Ghana). Il se focalise sur les modèles sémantiques et la nature pragmatique des métaphores basées sur ani et leur emploi dans une variété de contextes. En akan, les expressions indiquant les parties du corps ont des significations étendues qui gardent encore une certaine relation avec les mots originaux. Les parties du corps agissent ainsi comme les items lexicaux productifs pour la dérivation sémantique et métaphorique. -

Delalorm, Cephas (2016) Documentation and Description of Sɛkpɛlé: a Ghana-Togo Mountain Language of Ghana . Phd Thesis. SOAS

Delalorm, Cephas (2016) Documentation and description of Sɛkpɛlé: a Ghana-Togo mountain language of Ghana . PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/22780 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. DOCUMENTATION AND DESCRIPTION OF SƐKPƐLÉ: A GHANA-TOGO MOUNTAIN LANGUAGE OF GHANA Cephas Delalorm Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in Field Linguistics 2016 Department of Linguistics SOAS, University of London 1 Cephas Delalorm Declaration for SOAS PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination.