Adjective Attribution (Studies in Diversity Linguistics 2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice | RSACVP 2017 | 6-9 April 2017 | Suceava – Romania Rethinking Social Action

Available online at: http://lumenpublishing.com/proceedings/published-volumes/lumen- proceedings/rsacvp2017/ 8th LUMEN International Scientific Conference Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice | RSACVP 2017 | 6-9 April 2017 | Suceava – Romania Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice The Convertor Status of Article of Case and Number in the Romanian Language Diana-Maria ROMAN* https://doi.org/10.18662/lumproc.rsacvp2017.62 How to cite: Roman, D.-M. (2017). The Convertor Status of Article of Case and Number in the Romanian Language. In C. Ignatescu, A. Sandu, & T. Ciulei (eds.), Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice (pp.682-694). Suceava, Romania: LUMEN Proceedings https://doi.org/10.18662/lumproc.rsacvp2017.62 © The Authors, LUMEN Conference Center & LUMEN Proceedings. Selection and peer-review under responsibility of the Organizing Committee of the conference 8th LUMEN International Scientific Conference Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice | RSACVP 2017 | 6-9 April 2017 | Suceava – Romania The Convertor Status of Article of Case and Number in the Romanian Language Diana-Maria ROMAN1* Abstract This study is the outcome of research on the grammar of the contemporary Romanian language. It proposes a discussion of the marked nominalization of adjectives in Romanian, the analysis being focused on the hypostases of the convertor (nominalizer). Within this area of research, contemporary scholarly treaties have so far accepted solely nominalizers of the determinative article type (definite and indefinite) and nominalizers of the vocative desinence type, in the singular. However, with regard to the marked conversion of an adjective to the large class of nouns, the phenomenon of enclitic articulation does not always also entail the individualization of the nominalized adjective, as an expression of the category of definite determination. -

Possessive Agreement Turned Into a Derivational Suffix Katalin É. Kiss 1

Possessive agreement turned into a derivational suffix Katalin É. Kiss 1. Introduction The prototypical case of grammaticalization is a process in the course of which a lexical word loses its descriptive content and becomes a grammatical marker. This paper discusses a more complex type of grammaticalization, in the course of which an agreement suffix marking the presence of a phonologically null pronominal possessor is reanalyzed as a derivational suffix marking specificity, whereby the pro cross-referenced by it is lost. The phenomenon in question is known from various Uralic languages, where possessive agreement appears to have assumed a determiner-like function. It has recently been a much discussed question how the possessive and non-possessive uses of the agreement suffixes relate to each other (Nikolaeva 2003); whether Uralic definiteness-marking possessive agreement has been grammaticalized into a definite determiner (Gerland 2014), or it has preserved its original possessive function, merely the possessor–possessum relation is looser in Uralic than in the Indo-Europen languages, encompassing all kinds of associative relations (Fraurud 2001). The hypothesis has also been raised that in the Uralic languages, possessive agreement plays a role in organizing discourse, i.e., in linking participants into a topic chain (Janda 2015). This paper helps to clarify these issues by reconstructing the grammaticalization of possessive agreement into a partitivity marker in Hungarian, the language with the longest documented history in the Uralic family. Hungarian has two possessive morphemes functioning as a partitivity marker: -ik, an obsolete allomorph of the 3rd person plural possessive suffix, and -(j)A, the productive 3rd person singular possessive suffix. -

Prior Linguistic Knowledge Matters : the Use of the Partitive Case In

B 111 OULU 2013 B 111 UNIVERSITY OF OULU P.O.B. 7500 FI-90014 UNIVERSITY OF OULU FINLAND ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS ACTA SERIES EDITORS HUMANIORAB Marianne Spoelman ASCIENTIAE RERUM NATURALIUM Marianne Spoelman Senior Assistant Jorma Arhippainen PRIOR LINGUISTIC BHUMANIORA KNOWLEDGE MATTERS University Lecturer Santeri Palviainen CTECHNICA THE USE OF THE PARTITIVE CASE IN FINNISH Docent Hannu Heusala LEARNER LANGUAGE DMEDICA Professor Olli Vuolteenaho ESCIENTIAE RERUM SOCIALIUM University Lecturer Hannu Heikkinen FSCRIPTA ACADEMICA Director Sinikka Eskelinen GOECONOMICA Professor Jari Juga EDITOR IN CHIEF Professor Olli Vuolteenaho PUBLICATIONS EDITOR Publications Editor Kirsti Nurkkala UNIVERSITY OF OULU GRADUATE SCHOOL; UNIVERSITY OF OULU, FACULTY OF HUMANITIES, FINNISH LANGUAGE ISBN 978-952-62-0113-9 (Paperback) ISBN 978-952-62-0114-6 (PDF) ISSN 0355-3205 (Print) ISSN 1796-2218 (Online) ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS B Humaniora 111 MARIANNE SPOELMAN PRIOR LINGUISTIC KNOWLEDGE MATTERS The use of the partitive case in Finnish learner language Academic dissertation to be presented with the assent of the Doctoral Training Committee of Human Sciences of the University of Oulu for public defence in Keckmaninsali (Auditorium HU106), Linnanmaa, on 24 May 2013, at 12 noon UNIVERSITY OF OULU, OULU 2013 Copyright © 2013 Acta Univ. Oul. B 111, 2013 Supervised by Docent Jarmo H. Jantunen Professor Helena Sulkala Reviewed by Professor Tuomas Huumo Associate Professor Scott Jarvis Opponent Associate Professor Scott Jarvis ISBN 978-952-62-0113-9 (Paperback) ISBN 978-952-62-0114-6 (PDF) ISSN 0355-3205 (Printed) ISSN 1796-2218 (Online) Cover Design Raimo Ahonen JUVENES PRINT TAMPERE 2013 Spoelman, Marianne, Prior linguistic knowledge matters: The use of the partitive case in Finnish learner language University of Oulu Graduate School; University of Oulu, Faculty of Humanities, Finnish Language, P.O. -

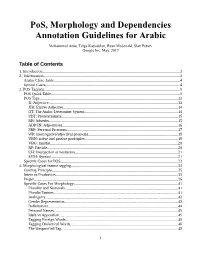

Pos, Morphology and Dependencies Annotation Guidelines for Arabic

PoS, Morphology and Dependencies Annotation Guidelines for Arabic Mohammed Attia, Tolga Kayadelen, Ryan Mcdonald, Slav Petrov Google Inc. May, 2017 Table of Contents 1. Introduction............................................................................................................................................2 2. Tokenization...........................................................................................................................................3 Arabic Clitic Table................................................................................................................................4 Special Cases.........................................................................................................................................4 3. POS Tagging..........................................................................................................................................8 POS Quick Table...................................................................................................................................8 POS Tags.............................................................................................................................................13 JJ: Adjective....................................................................................................................................13 JJR: Elative Adjective.....................................................................................................................14 DT: The Arabic Determiner System...............................................................................................14 -

Spatial Semantics, Case and Relator Nouns in Evenki

Spatial semantics, case and relator nouns in Evenki Lenore A. Grenoble University of Chicago Evenki, a Northwest Tungusic language, exhibits an extensive system of nominal cases, deictic terms, and relator nouns, used to signal complex spatial relations. The paper describes the use and distribution of the spatial cases which signal stative and dynamic relations, with special attention to their semantics within a framework using fundamental Gestalt concepts such as Figure and Ground, and how they are used in combination with deictics and nouns to signal specific spatial semantics. Possible paths of grammaticalization including case stacking, or Suffixaufnahme, are dis- cussed. Keywords: spatial cases, case morphology, relator noun, deixis, Suf- fixaufnahme, grammaticalization 1. Introduction Case morphology and relator nouns are extensively used in the marking of spa- tial relations in Evenki, a Tungusic language spoken in Siberia by an estimated 4802 people (All-Russian Census 2010). A close analysis of the use of spatial cases in Evenki provides strong evidence for the development of complex case morphemes from adpositions. Descriptions of Evenki generally claim the exist- ence of 11–15 cases, depending on the dialect. The standard language is based on the Poligus dialect of the Podkamennaya Tunguska subgroup, from the Southern dialect group, now moribund. Because it forms the basis of the stand- ard (or literary) language and as such has been relatively well-studied and is somewhat codified, it usually serves as the point of departure in linguistic de- scriptions of Evenki. However, the written language is to a large degree an artifi- cial construct which has never achieved usage in everyday conversation: it does not function as a norm which cuts across dialects. -

Elevation As a Category of Grammar: Sanzhi Dargwa and Beyond Received May 11, 2018; Revised August 20, 2018

Linguistic Typology 2019; 23(1): 59–106 Diana Forker Elevation as a category of grammar: Sanzhi Dargwa and beyond https://doi.org/10.1515/lingty-2019-0001 Received May 11, 2018; revised August 20, 2018 Abstract: Nakh-Daghestanian languages have encountered growing interest from typologists and linguists from other subdiscplines, and more and more languages from the Nakh-Daghestanian language family are being studied. This paper provides a grammatical overview of the hitherto undescribed Sanzhi Dargwa language, followed by a detailed analysis of the grammaticalized expression of spatial elevation in Sanzhi. Spatial elevation, a topic that has not received substantial attention in Caucasian linguistics, manifests itself across different parts of speech in Sanzhi Dargwa and related languages. In Sanzhi, elevation is a deictic category in partial opposition with participant- oriented deixis/horizontally-oriented directional deixis. This paper treats the spatial uses of demonstratives, spatial preverbs and spatial cases that express elevation as well as the semantic extension of this spatial category into other, non-spatial domains. It further compares the Sanzhi data to other Caucasian and non-Caucasian languages and makes suggestions for investigating elevation as a subcategory within a broader category of topographical deixis. Keywords: Sanzhi Dargwa, Nakh-Daghestanian languages, elevation, deixis, demonstratives, spatial cases, spatial preverbs 1 Introduction Interest in Nakh-Daghestanian languages in typology and in other linguistic subdisciplines has grown rapidly in recent years, with an active community of linguists from Russia and other countries. The goal of the present paper is to pour more oil into this fire and perhaps to entice new generations of scholars to join the throng. -

5 Adjectives and Adverbs

5 ADJECTIVES AND ADVERBS 1 Choose the correct alternative in the sentences below. If you find both alternatives acceptable, explain any difference in meaning. a. All the venues are easy/easily accessible. b. There’s a possible/possibly financial problem. c. We admired the wonderful/wonderfully panorama. d. Our neighbours are (simple)/simply people who live near us. Although less likely in this case, the adjective “simple” could be used as a premodifier to describe the noun (that is, the neighbours are not sophisticated people). Since the sentence seems to be a more general description of neighbours, however, the adverb “simply” is the more likely choice. The adverb serves as a comment on the part of the speaker. e. They seemed happy/happily about George’s victory. f. Similar/Similarly teams of medical advisers were called upon. g. Something in here smells horrible/horribly. Normally an adjective will follow a linking verb to describe a quality of the subject ref- erent. However, the adverb “horribly” can be used to refer to the intensity of the smell. h. This cream will give you a beautiful/beautifully smooth complexion. i. Particular/Particularly groups such as recent immigrants felt their needs were being overlooked. INTRODUCING ENGLISH GRAMMAR, THIRD EDITION KEY TO EXERCISES 5 Adjectives and Adverbs The adjective “particular” premodifies or describes the noun “groups”, whereas the use of the adverb “particularly” functions as a comment on the part of the speaker. 2 Explain the difference in form and meaning between the members of each pair. a. 1 She is a natural blonde. -

University of Education, Winneba College Of

University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION, WINNEBA COLLEGE OF LANGUAGES EDUCATION, AJUMAKO THE SYNTAX OF THE GONJA NOUN PHRASE JACOB SHAIBU KOTOCHI May, 2017 i University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION, WINNEBA COLLEGE OF LANGUAGES EDUCATION, AJUMAKO THE SYNTAX OF THE GONJA NOUN PHRASE JACOB SHAIBU KOTOCHI 8150260007 A thesis in the Department of GUR-GONJA LANGUAGES EDUCATION, COLLEGE OF LANGUAGES EDUCATION, submitted to the school of Graduate Studies, UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION, WINNEBA in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the Master of Philosophy in Ghanaian Language Studies (GONJA) degree. ii University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh DECLARATION I, Jacob Shaibu Kotochi, declare that this thesis, with the exception of quotations and references contained in published works and students creative writings which have all been identified and duly acknowledged, is entirely my own original work, and it has not been submitted, either in part or whole, for another degree elsewhere. Signature: …………………………….. Date: …………………………….. SUPERVISOR’S DECLARATION I, Dr. Samuel Awinkene Atintono, hereby declare that the preparation and presentation of this thesis were supervised in accordance with the guidelines for supervision of thesis as laid down by the University of Education, Winneba. Signature: …………………………….. Date: …………………………….. iii University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to express my gratitude to Dr. Samuel Awinkene Atintono of the Department of Gur-Gonja Languages Education, College of Languages Education for being my guardian, mentor, lecturer and supervisor throughout my university Education and the writing of this research work. -

1 Tsezian Languages Bernard Comrie, Maria Polinsky, and Ramazan

Tsezian Languages Bernard Comrie, Maria Polinsky, and Ramazan Rajabov Max-Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany University of California, San Diego, USA Makhachkala, Russia 1. Sociolinguistic Situation1 The Tsezian (Tsezic, Didoic) languages form part of the Daghestanian branch of the Nakh-Daghestanian (East Caucasian) language family. They form one branch of an Avar-Andi-Tsez grouping within the family, the other branch of this grouping being Avar-Andi. Five Tsezian languages are conventionally recognized: Khwarshi (Avar x∑arßi, Khwarshi a¥’ilqo), Tsez (Avar, Tsez cez, also known by the Georgian name Dido), Hinuq (Avar, Hinuq hinuq), Bezhta (Avar beΩt’a, Bezhta beΩ¥’a. also known by the Georgian name Kapuch(i)), and Hunzib (Avar, Hunzib hunzib), although the Inkhokwari (Avar inxoq’∑ari, Khwarshi iqqo) dialect of Khwarshi and the Sagada (Avar sahada, Tsez so¥’o) dialect of Tsez are highly divergent. Tsez, Hinuq, Bezhta, and Hunzib are spoken primarily in the Tsunta district of western Daghestan, while Khwarshi is spoken primarily to the north in the adjacent Tsumada district, separated from the other Tsezian languages by high mountains. (See map 1.) In addition, speakers of Tsezian languages are also to be found as migrants to lowland Daghestan, occasionally in other parts of Russia and in Georgia. Estimates of the number of speakers are given by van den Berg (1995) as follows, for 1992: Tsez 14,000 (including 6,500 in the lowlands); Bezhta 7,000 (including 2,500 in the lowlands); Hunzib 2,000 (including 1,300 in the lowlands); Hinuq 500; Khwarshi 1,500 (including 600 in the lowlands). -

Syntax of Hungarian. Nouns and Noun Phrases, Volume 2

Comprehensive Grammar Resources Series editors: Henk van Riemsdijk, István Kenesei and Hans Broekhuis Syntax of Hungarian Nouns and Noun Phrases Volume 2 Edited by Gábor Alberti and Tibor Laczkó Syntax of Hungarian Nouns and Noun Phrases Volume II Comprehensive Grammar Resources With the rapid development of linguistic theory, the art of grammar writing has changed. Modern research on grammatical structures has tended to uncover many constructions, many in depth properties, many insights that are generally not found in the type of grammar books that are used in schools and in fields related to linguistics. The new factual and analytical body of knowledge that is being built up for many languages is, unfortunately, often buried in articles and books that concentrate on theoretical issues and are, therefore, not available in a systematized way. The Comprehensive Grammar Resources (CGR) series intends to make up for this lacuna by publishing extensive grammars that are solidly based on recent theoretical and empirical advances. They intend to present the facts as completely as possible and in a way that will “speak” to modern linguists but will also and increasingly become a new type of grammatical resource for the semi- and non- specialist. Such grammar works are, of necessity, quite voluminous. And compiling them is a huge task. Furthermore, no grammar can ever be complete. Instead new subdomains can always come under scientific scrutiny and lead to additional volumes. We therefore intend to build up these grammars incrementally, volume by volume. In view of the encyclopaedic nature of grammars, and in view of the size of the works, adequate search facilities must be provided in the form of good indices and extensive cross-referencing. -

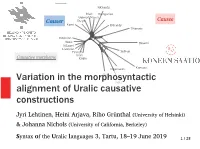

Variation in the Morphosyntactic Alignment of Uralic Causative

0.1 NKhanty Mari Hungarian Udmurt Mansi Causer Erzya Causee Komi EKhanty TNenets Estonian Votic SSaami NSaami Livonian Finnish Selkup Inari Causative morpheme Kildin Kamass Nganasan Variation in the morphosyntacticSEst Veps alignment of Uralic causative constructions Jyri Lehtinen, Heini Arjava, Riho Grünthal (University of Helsinki) & Johanna Nichols (University of California, Berkeley) Syntax of the Uralic languages 3, Tartu, 18–19 June 2019 1 / 28 Causative alternation in Uralic ● Extension into the Uralic languages of the approach described in Nichols et al. (2004) – Lexical valence orientation: Transitivizing vs. detransitivizing (or causativizing vs. decausativizing) languages – In addition, phylogenetic models of Uralic language relationships – Phylogenies taking into account both valence orientation (grammar) and origin of relevant forms (etymology) 2 / 28 Causative alternation in Uralic ● 22 Uralic language varieties: – South Sámi, North Sámi, Inari Sámi, Kildin Sámi – Finnish, Veps, Votic, Estonian, Southern Estonian, Livonian – Erzya – Meadow Mari – Udmurt, Komi-Zyrian – Hungarian, Northern Mansi, Eastern Khanty, Northern Khanty – Tundra Nenets, Nganasan, Kamass, Selkup 3 / 28 Alternation in animate verbs ● For animate verbs, all surveyed languages are predominantly causativizing – e.g. ’eat’ / ’feed’: North Sámi borrat / borahit; Estonian sööma / söötma; Northern Mansi tēŋkwe / tittuŋkwe; Hungarian eszik / etet ● Little decaus., much caus.: North Sámi, S Estonian, Mari, Samoyed; much decaus., little caus.: Kildin Sámi, Livonian, -

Syntactic Classes of the Arabic Active Participle and Their Equivalents in Translation: a Comparative Study in Two English Quranic Translations

Syntactic Classes of the Arabic Active Participle and their Equivalents in Translation: A Comparative Study in Two English Quranic Translations Hassan A. H. Gadalla, Ph.D. in Linguistics, Assiut University, Egypt [Published in the Bulletin of the Faculty of Arts, Assiut University, Egypt. Vol. 18, Jan. 2005, pp. 1-37.] 0. Introduction: This study attempts to provide an analysis of the syntactic classes of Arabic active participle forms and discuss their translations based on a comparative study of two English Quranic translations by Ali (1934) and Pickthall (1930). It starts with a brief introduction to the active participle in Arabic and the Arab grammarians' discussion of its syntactic classes. Then, it explains the study aim and technique. The third section presents an analysis of the results of the study by discussing the various renderings of the Arabic active participle in the two English translations of the Quran. For the phonemic symbols used to transcribe Arabic data, see Appendix (1) and for the symbols and abbreviations employed in the study, see Appendix (2). 1 1. Syntactic Classes of the Arabic Active Participle: The active participle (AP) is a morphological form derived from a verb to refer to the person or animate being that performs the action denoted by the verb. In Classical and Modern Standard Arabic grammars, it is called /?ism-u l-faa9il/ 'noun of the agent' and it has two patterns; one formed from the primary triradical verb and the other from the derived triradical as well as the quadriradical verbs. The former has the form [Faa9iL], e.g.