The Relationship Between Attitudes and Perspectives of American

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sign Language Typology Series

SIGN LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY SERIES The Sign Language Typology Series is dedicated to the comparative study of sign languages around the world. Individual or collective works that systematically explore typological variation across sign languages are the focus of this series, with particular emphasis on undocumented, underdescribed and endangered sign languages. The scope of the series primarily includes cross-linguistic studies of grammatical domains across a larger or smaller sample of sign languages, but also encompasses the study of individual sign languages from a typological perspective and comparison between signed and spoken languages in terms of language modality, as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to sign language typology. Interrogative and Negative Constructions in Sign Languages Edited by Ulrike Zeshan Sign Language Typology Series No. 1 / Interrogative and negative constructions in sign languages / Ulrike Zeshan (ed.) / Nijmegen: Ishara Press 2006. ISBN-10: 90-8656-001-6 ISBN-13: 978-90-8656-001-1 © Ishara Press Stichting DEF Wundtlaan 1 6525XD Nijmegen The Netherlands Fax: +31-24-3521213 email: [email protected] http://ishara.def-intl.org Cover design: Sibaji Panda Printed in the Netherlands First published 2006 Catalogue copy of this book available at Depot van Nederlandse Publicaties, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag (www.kb.nl/depot) To the deaf pioneers in developing countries who have inspired all my work Contents Preface........................................................................................................10 -

Critical Inquiry in Language Studies New Directions in ASL-English

This article was downloaded by: [Gallaudet University], [Adam Stone] On: 26 August 2014, At: 09:23 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Critical Inquiry in Language Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hcil20 New Directions in ASL-English Bilingual Ebooks Adam Stonea a Gallaudet University Published online: 22 Aug 2014. To cite this article: Adam Stone (2014) New Directions in ASL-English Bilingual Ebooks, Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 11:3, 186-206, DOI: 10.1080/15427587.2014.936242 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2014.936242 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Negation in Kata Kolok Grammaticalization Throughout Three Generations of Signers

UNIVERSITEIT VAN AMSTERDAM Graduate School for Humanities Negation in Kata Kolok Grammaticalization throughout three generations of signers Master’s Thesis Hannah Lutzenberger Student number: 10852875 Supervised by: Dr. Roland Pfau Dr. Vadim Kimmelman Dr. Connie de Vos Amsterdam 2017 Abstract (250 words) Although all natural languages have ways of expressing negation, the linguistic realization is subject to typological variation (Dahl 2010; Payne 1985). Signed languages combine manual signs and non-manual elements. This leads to an intriguing dichotomy: While non-manual marker(s) alone are sufficient for negating a proposition in some signed languages (non- manual dominant system), the use of a negative manual sign is required in others (manual dominant system) (Zeshan 2004, 2006). Kata Kolok (KK), a young signing variety used in a Balinese village with a high incidence of congenital deafness (de Vos 2012; Winata et al. 1995), had previously been classified as an extreme example of the latter type: the manual sign NEG functions as the main negator and a negative headshake remains largely unused (Marsaja 2008). Adopting a corpus-based approach, the present study reevaluates this claim. The analysis of intergenerational data of six deaf native KK signers from the KK Corpus (de Vos 2016) reveals that the classification of KK negation is not as straightforward as formerly suggested. Although KK signers make extensive use of NEG, a negative headshake is widespread as well. Furthermore, signers from different generations show disparate tendencies in the use of specific markers. Specifically, the involvement of the manual negator slightly increases over time, and the headshake begins to spread within the youngest generation of signers. -

![Arxiv:2012.11981V1 [Cs.HC] 22 Dec 2020 That Deaf People Can Use in Order to Communicate in a Sign Language [6]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4176/arxiv-2012-11981v1-cs-hc-22-dec-2020-that-deaf-people-can-use-in-order-to-communicate-in-a-sign-language-6-1234176.webp)

Arxiv:2012.11981V1 [Cs.HC] 22 Dec 2020 That Deaf People Can Use in Order to Communicate in a Sign Language [6]

Speak with signs: Active learning platform for Greek Sign Language, English Sign Language, and their translation Maria Papatsimouli1, Lazaros Lazaridis1, Konstantinos-Filippos Kollias1, Ioannis Skordas1, and George F. Fragulis1;∗ 1Laboratory of Robotics, Embedded and Integrated Systems, Dept. of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Western Macedonia, Hellas Abstract. Sign Language is used to facilitate the communication between Deaf and non-Deaf people. It uses signs-words with basic structural elements such as handshape, parts of face, body or space, and the orientation of the fingers-palm. Sign Languages vary from people to people and from country to country and evolve as spoken languages. In the current study, an application which aims at Greek Sign Language and English Sign Language learning by hard of hearing people and talking people, has been developed. The application includes grouped signs in alphabetical order. The user can find Greek Sign Language signs, English sign language signs and translate from Greek sign language to English sign language. The written word of each sign, and the corresponding meaning are displayed. In addition, the sound is activated in order to enable users with partial hearing loss to hear the pronunciation of each word. The user is also provided with various tasks in order to enable an interaction of the knowledge acquired by the user. This interaction is offered mainly by multiple- choice tasks, incorporating text or video. The current application is not a simple sign language dictionary as it provides the interactive participation of users. It is a platform for Greek and English sign language active learning. Keywords: Deaf, Sign Language, Greek Sign Lan- 1.1 Deaf and Sign Languages guage, English Sign Language, Learning, Interaction, Ac- tive Learning, Open Source software. -

Variation in Mouthing Occurrence in Greek Sign Language (GSL); the Case of Register and Grammatical Class

Variation in mouthing occurrence in Greek Sign Language (GSL); the case of register and grammatical class By Ioanna Tsourma A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF RESEARCH Department of English Language and Applied Linguistics School of English Drama and American and Canadian Studies University of Birmingham 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis explores the mouthing occurrence rates across different registers (informative and narrative) and grammatical classes in Greek Sign Language (GSL). A general consensus has been reached dividing mouth activity into at least two subcategories of mouth actions: ‗mouth gestures‘ and ‗mouthings‘ (see edited volume by Boyes Braem & Sutton-Spence, 2001). Data consist of 45‘ of video recordings from six native and near-native1 signers, transcribed using a software tool for annotating multimedia video recordings (ELAN). In an effort to gain some control over the influence of individual variation, all six signers have an example of SL production in both registers. A combination of semantic, syntactic and morphological criteria (Schwager & Zeshan, 2008) has been utilized in order to classify all manual signs for their grammatical class, in an effort to study the potential impact of grammatical class on mouthing occurrence. -

A Plan for Developing an Auslan Communication Technologies Pipeline

A Plan for Developing an Auslan Communication Technologies Pipeline Jessica Korte1[0000−0002−4412−7199], Axel Bender2, Guy Gallasch2, Janet Wiles1[0000−0002−4051−4116], and Andrew Back1[0000−0001−5474−1910] 1 The University of Queensland, Australia fj.korte,j.wiles,[email protected] 2 Defense Science and Technology, Australia fAxel.Bender,[email protected] Abstract. AI techniques for mainstream spoken languages have seen a great deal of progress in recent years, with technologies for transcrip- tion, translation and text processing becoming commercially available. However, no such technologies have been developed for sign languages, which, as visual-gestural languages, require multimodal processing ap- proaches. This paper presents a plan to develop an Auslan Communi- cation Technologies Pipeline (Auslan CTP), a prototype AI system en- abling Auslan-in, Auslan-out interactions, to demonstrate the feasibility of Auslan-based machine interaction and language processing. Such a system has a range of applications, including gestural human-machine interfaces, educational tools, and translation. Keywords: Auslan, Australian Sign Language, sign language recogni- tion, sign language production, sign language processing Fig. 1. The proposed Auslan Communication Technologies Pipeline architecture. Each module represents a segment of functionality which requires the development of specific AI approaches: the Recognition Module, intended to recognise sign input, requires devel- opment of Auslan recognition as a multimodal language; the Processing Module, which provides the functionality of the pipeline, requires Natural Sign Language Processing; and the Production Module, which will output Auslan signing, requires human-like pro- duction of sign output that is acceptable to the Deaf community. -

DEAF INTERPRETING in EUROPE Exploring Best Practice in the Field

DEAF INTERPRETING IN EUROPE Exploring best practice in the field Christopher Stone, Editor 1 Deaf Interpreting in Europe. Exploring best practice in the field. Editor: Christopher Stone. Danish Deaf Association. 2018. ISBN 978-87-970271-0-3 Co-funded by the Erasmus+ programme of the European Union FSupportedunded by bythe the Co-funded by the Erasmus+ programmeprogramme Erasmus+ programme of the European Union of the European UnionUnion 2 How to access the emblem You can download the emblem from our website in two different formats. After downloading the .zip file, please click 'extract all files' or unzip the folder to access the .eps file required. The different formats are: . JPG: standard image format (no transparency). Ideal for web use because of the small file size. EPS: requires illustration software such as Adobe Illustrator. Recommended for professional use on promotional items and design. Some visual do’s and don’ts ✓. Do resize the emblem if needed. The minimum size it can be is 10mm in height. Co-funded by the Erasmus+ programme of the European Union Co-funded by the Erasmus+ programme of the European Union Preface This publication is the outcome of the Erasmus+ project Developing Deaf Interpreting. The project has been underway since September 2015 and has been a cooperation between Higher Educational Institutions in Europe undertaking deaf interpreter training, as well as national and European NGOs in the field. The project partners are: Institute for German Sign Language (IDGS) at Hamburg University, Coimbra Polytechnic Institute (IPC), Humak University of Applied Sciences, European Forum of Sign Language Interpreters (efsli), and the Danish Deaf Association (DDA). -

Sign Language Recognition, Generation, And

Sign Language Recognition, Generation, and Translation: An Interdisciplinary Perspective Danielle Bragg1 Oscar Koller2 Mary Bellard2 Larwan Berke3 Patrick Boudreault4 Annelies Braffort5 Naomi Caselli6 Matt Huenerfauth3 Hernisa Kacorri7 Tessa Verhoef8 Christian Vogler4 Meredith Ringel Morris1 1Microsoft Research - Cambridge, MA USA & Redmond, WA USA {danielle.bragg,merrie}@microsoft.com 2Microsoft - Munich, Germany & Redmond, WA USA {oscar.koller,marybel}@microsoft.com 3Rochester Institute of Technology - Rochester, NY USA {larwan.berke,matt.huenerfauth}@rit.edu 4Gallaudet University - Washington, DC USA {patrick.boudreault,christian.vogler}@gallaudet.edu 5LIMSI-CNRS - Orsay Cedex, France [email protected] 6Boston University - Boston, MA USA [email protected] 7University of Maryland - College Park, MD USA [email protected] 8Leiden University - Leiden, Netherlands [email protected] ABSTRACT of the Deaf, there are over 300 sign languages used around Developing successful sign language recognition, generation, the world, and 70 million deaf people using them [89]. Sign and translation systems requires expertise in a wide range of languages, like all languages, are naturally evolved, highly felds, including computer vision, computer graphics, natural structured systems governed by a set of linguistic rules. They language processing, human-computer interaction, linguistics, are distinct from spoken languages – i.e., American Sign Lan- and Deaf culture. Despite the need for deep interdisciplinary guage (ASL) is not a manual form of English – and do not knowledge, existing research occurs in separate disciplinary have standard written forms. However, the vast majority of silos, and tackles separate portions of the sign language pro- communications technologies are designed to support spoken cessing pipeline. This leads to three key questions: 1) What or written language (which excludes sign languages), and most does an interdisciplinary view of the current landscape reveal? hearing people do not know a sign language. -

LEARNING MATERIALS for GREEK SIGN LANGUAGE AS a FIRST LANGUAGE Materiais De Aprendizagem Para a Língua De Sinais Grega Como Primeira Língua

INES | Revista Espaço | Rio de Janeiro | nº 45 | jan-jun | 2016 LEARNING MATERIALS FOR GREEK SIGN LANGUAGE AS A FIRST LANGUAGE Materiais de aprendizagem para a Língua De Sinais Grega como primeira língua Dr. Maria Mertzani49 RESUMO ABSTRACT The National Strategic Reference O National Strategic Reference Fra- Framework (NSRF) the years 2007-2013 mework (NSRF) realizou, nos anos realised the project entitled "Design 2007-2013, o projeto intitulado "Con- and development of accessible educa- cepção e desenvolvimento de materi- ais educativos acessíveis para alunos tional materials for students with disa- com deficiência - Ação Horizontal" bility-Horizontal Action‖ with the scope com o objetivo de criar materiais to create educational materials for educativos para crianças com necessi- children with special needs. In this, dades especiais. A Língua de Sinais Greek Sign Language (GSL) as a first Grega (GSL) como primeira língua (L1) language (L1) in school education was na educação escolar foi seguida, com followed, based on the new Special base na nova Lei de Educação Especial Education Law 3699/2008 and the 2004 3699/2008 e no currículo de 2004 GSL, e foram produzidos seis tipos de GSL curriculum, and six types of educa- materiais educativos para a aprendiza- tional materials for the learning of the gem da língua pela primeira vez no language were produced for the first sistema educacional nacional grego. time in Greek national educational Este artigo tem como objetivo discutir system. This paper aims at discussing o desenho e os princípios -

Statistical Machine Translation for Greek to Greek Sign Language Using Parallel Corpora Produced Via Rule- Based Machine Translation

Statistical Machine Translation for Greek to Greek Sign Language Using Parallel Corpora Produced via Rule- Based Machine Translation Dimitrios Kouremenos1, Klimis Ntalianis2, Giorgos Siolas3 and Andreas Stafylopatis4 1 School of Electrical & Computer Engineering National Technical University of Athens 15780 Athens, Greece [email protected] 2 Department of Business Administration University of West Attica Athens, Greece [email protected] 3 School of Electrical & Computer Engineering National Technical University of Athens 15780 Athens, Greece [email protected] 4 School of Electrical & Computer Engineering National Technical University of Athens 15780 Athens, Greece [email protected] Abstract. One of the objectives of Assistive Technologies is to help people with disabilities communicate with others and provide means of access to in- formation. As an aid to Deaf people, we present in this work a novel prototype Rule-Based Machine Translation (RBMT) system for the creation of large qual- ity written Greek text to Greek Sign Language (GSL) glossed corpora. In par- ticular, the proposed RBMT system supports the professional translator of GSL to produce high quality parallel Greek text - GSL glossed corpus, which is then used as training data by the Statistical Machine Translation (SMT) MOSES [1] application system. It should be noted that the whole process is robust and flex- ible, since it does not demand deep grammar knowledge of GSL. With this work we manage to overcome the two biggest obstacles in Natural Processing Language (NLP) of GSL. Firstly, the lack of written system and secondly the lack of grammar and finally we have been able to lay the foundations for an au- tonomous translation system of Greek text to GSL. -

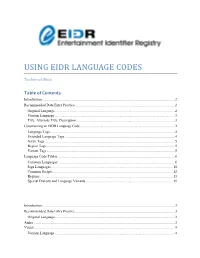

Using Eidr Language Codes

USING EIDR LANGUAGE CODES Technical Note Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Recommended Data Entry Practice .............................................................................................................. 2 Original Language..................................................................................................................................... 2 Version Language ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Title, Alternate Title, Description ............................................................................................................. 3 Constructing an EIDR Language Code ......................................................................................................... 3 Language Tags .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Extended Language Tags .......................................................................................................................... 4 Script Tags ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Region Tags ............................................................................................................................................. -

MS-ASL: a Large-Scale Data Set and Benchmark for Understanding American Sign Language

VAEZI JOZE, KOLLER: MS-ASL 1 MS-ASL: A Large-Scale Data Set and Benchmark for Understanding American Sign Language Hamid Reza Vaezi Joze Microsoft [email protected] Redmond, WA, USA Oscar Koller Microsoft [email protected] Munich, Germany Abstract Sign language recognition is a challenging and often underestimated problem com- prising multi-modal articulators (handshape, orientation, movement, upper body and face) that integrate asynchronously on multiple streams. Learning powerful statistical models in such a scenario requires much data, particularly to apply recent advances of the field. However, labeled data is a scarce resource for sign language due to the enor- mous cost of transcribing these unwritten languages. We propose the first real-life large-scale sign language data set comprising over 25,000 annotated videos, which we thoroughly evaluate with state-of-the-art methods from sign and related action recognition. Unlike the current state-of-the-art, the data set allows to investigate the generalization to unseen individuals (signer-independent test) in a realistic setting with over 200 signers. Previous work mostly deals with limited vocabulary tasks, while here, we cover a large class count of 1000 signs in challenging and unconstrained real-life recording conditions. We further propose I3D, known from video classifications, as a powerful and suitable architecture for sign language recogni- tion, outperforming the current state-of-the-art by a large margin. The data set is publicly available to the community. 1 Introduction In the US, approximately around 500,000 people use American sign language (ASL) as primary means of communication [49]. ASL is also used in Canada, Mexico and 20 other countries.