Sonic Spaces, Spiritual Bodies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Angriff Der Melancholie Malen, Anti-Kriegs-Demos, Fußball: Für Musik Haben Die Einst So Coolen Futuristen Von Massive Attack Nur Noch Wenig Zeit

Angriff der Melancholie Malen, Anti-Kriegs-Demos, Fußball: Für Musik haben die einst so coolen Futuristen von Massive Attack nur noch wenig Zeit. VON CHRISTOPH DALLACH Dummerweise hat das neue Album jede nur mögliche Werbung nötig. Denn so hoch die Erwartungen an das einstige Pop-Avantgarde-Genie wa- rfolg im Pop ist auch immer eine Frage des ren, so bitter werden sie nun enttäuscht: neun Moll-Electro-Hop-Balladen, Timings. Und was das betrifft, hat das pa- die grau und bedeutungsschwanger ohne jeden Pep dahinwummern. Auch Ezifistische britische Musiker-Kollektiv, das die üblichen Gastsänger wie Reggae-Veteran Horace Andy und die kurz- sich ganz martialisch Massive Attack nennt, kei- haarige Heulsuse Sinéad O’Connor helfen da nichts mehr. ne glückliche Hand. Als Anfang der neunziger Der Aussetzer der Bristoler Elektro-Stars zeigt, wie schwierig es ist, im Mu- Jahre die erste Single seines Debüt-Albums ãBlue sikgeschäft über mehrere Jahre innovativ zu bleiben. Das ist umso trauri- Lines“ erschien, verscheuchten die Amerikaner ger, als es der ganzen Branche derzeit an Innovationen mangelt. Dabei gerade Saddam Hussein aus Kuweit. Die Musiker waren Massive Attack mal eine Institution, die Ma§stäbe für die moderne beschlossen, zeitweilig die Attacke aus ihrem Na- Popmusik gesetzt hat. Ende der achtziger Jahre, hervorgegangen aus der men zu streichen. HipHop-DJ-Künstler-Gang Wild Bunch in der britischen Hafenstadt Bristol, In diesem Monat erscheint mit ã100th Window“ hatten Massive Attack prägenden Anteil an der Entstehung des so genann- (Virgin) das vierte Werk von Massive Attack, wie- ten TripHop. Einem Sound, der von gebremsten HipHop-Beats und ge- der gibt’s Krach zwischen dem Chef der Iraker pflegter Melancholie bestimmt wurde und bis heute in Cafés, Clubs und und den Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika, und Boutiquen nachhallt. -

Jah Free 2016

JAH FREE 2016 THE DUB ACTIVIST The unique sounds of JAH FREE MUSIC seems to have no boundaries, he really can’t contain or control the movement of his music or where it will take him next. The people really do have the power and it is their love, vibes and support which keeps Jah Free Music very much alive and well today. The man himself never having had a plan, tries to take a natural musical path of progression, following the vibes and trying to always stand for the positive, his most important aim is to bring a ‘one love’ message in his musical works and live shows for anyone who cares to listen. Jah Free has been involved in the UK, European and now global reggae music scene for some 35 years with Roots, Dub, Digital productions and remixes. He first started out playing keys, percussion and singing in his band Tallowah back in the late to early 70s/80s, the band was formed by himself and his musically talented friends. The band’s name was later to become “Bushfire”, remembered by most as a highly successful UK Roots band for its time. Even now people mention those times and the live shows they enjoyed. Bushfire were asked to perform outside of the UK in Europe at festivals notably taking its own Wango Riley Stage on the road with its own mixing desk and P.A included, this being where Jah Free first learnt his many skills in live mixing. Worth mentioning that the Wango Rileys stage went on to become a very well known stage on the festival circuit over its many years, but sadly burnt down in the 90s. -

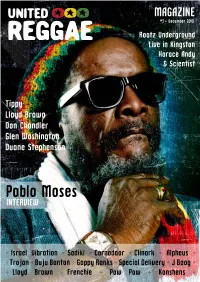

Pablo Moses INTERVIEW

MAGAZINE #3 - December 2010 Rootz Underground Live in Kingston Horace Andy & Scientist Tippy Lloyd Brown Don Chandler Glen Washington Duane Stephenson Pablo Moses INTERVIEW * Israel Vibration * Sadiki * Cornadoor * Clinark * Alpheus * * Trojan * Buju Banton * Gappy Ranks * Special Delivery * J Boog * * Lloyd Brown * Frenchie * Pow Pow * Konshens * United Reggae Mag #3 - December 2010 Want to read United Reggae as a paper magazine? In addition to the latest United Reggae news, views andNow videos you online can... each month you can now enjoy a free pdf version packed with most of United Reggae content from the last month.. SUMMARY 1/ NEWS •Lloyd Brown - Special Delivery - Own Mission Records - Calabash J Boog - Konshens - Trojan - Alpheus - Racer Riddim - Everlasting Riddim London International Ska Festival - Jamaican-roots.com - Buju Banton, Gappy Ranks, Irie Ites, Sadiki, Tiger Records 3 - 9 2/ INTERVIEWS •Interview: Tippy 11 •Interview: Pablo Moses 15 •Interview: Duane Stephenson 19 •Interview: Don Chandler 23 •Interview: Glen Washington 26 3/ REVIEWS •Voodoo Woman by Laurel Aitken 29 •Johnny Osbourne - Reggae Legend 30 •Cornerstone by Lloyd Brown 31 •Clinark - Tribute to Michael Jackson, A Legend and a Warrior •Without Restrictions by Cornadoor 32 •Keith Richards’ sublime Wingless Angels 33 •Reggae Knights by Israel Vibration 35 •Re-Birth by The Tamlins 36 •Jahdan Blakkamoore - Babylon Nightmare 37 4/ ARTICLES •Is reggae dying a slow death? 38 •Reggae Grammy is a Joke 39 •Meet Jah Turban 5/ PHOTOS •Summer Of Rootz 43 •Horace Andy and Scientist in Paris 49 •Red Strip Bold 2010 50 •Half Way Tree Live 52 All the articles in this magazine were previously published online on http://unitedreggae.com.This magazine is free for download at http://unitedreggae.com/magazine/. -

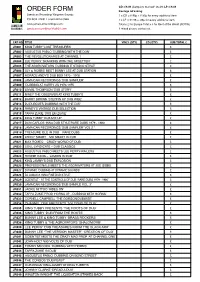

Order Form Order Form

CD: £9.49 (Samplers marked* £6.49) LP: £9.49 ORDER FORM Postage &Packing: Jamaican Recording/ Kingston Sounds 1 x CD = 0.95p + 0.35p for every additional item PO BOX 32691 London W14 OWH 1 x LP = £1.95 + .85p for every additional item JAMAICAN www.jamaicanrecordings.com Total x 2 for Europe Total x 3 for Rest of the World (ROTW) RECORDINGS [email protected] If mixed please contact us. CAT NO. TITLE VINLY (QTY) CD (QTY) SUB TOTAL £ JR001 KING TUBBY 'LOST TREASURES' £ JR002 AUGUSTUS PABLO 'DUBBING WITH THE DON' £ JR003 THE REVOLUTIONARIES AT CHANNEL 1 £ JR004 LEE PERRY 'SKANKING WITH THE UPSETTER' £ JR005 THE AGGROVATORS 'DUBBING IT STUDIO STYLE' £ JR006 SLY & ROBBIE MEET BUNNY LEE AT DUB STATION £ JR007 HORACE ANDY'S DUB BOX 1973 - 1976 £ JR008 JAMAICAN RECORDINGS 'DUB SAMPLER' £ JR009 'DUBBING AT HARRY J'S 1970-1975 £ JR010 LINVAL THOMPSON 'DUB STORY' £ JR011 NINEY THE OBSERVER AT KING TUBBY'S £ JR012 BARRY BROWN 'STEPPIN UP DUB WISE' £ JR013 DJ DUBCUTS 'DUBBING WITH THE DJS' £ JR014 RANDY’S VINTAGE DUB SELECTION £ JR015 TAPPA ZUKIE ‘DUB EM ZUKIE’ £ JR016 KING TUBBY ‘DUB MIX UP’ £ JR017 DON CARLOS ‘INNA DUB STYLE’RARE DUBS 1979 - 1980 £ JR018 JAMAICAN RECORDINGS 'DUB SAMPLER' VOL 2 * £ JR019 TREASURE ISLE IN DUB – RARE DUBS £ JR020 LEROY SMART – MR SMART IN DUB £ JR021 MAX ROMEO – CRAZY WORLD OF DUB £ JR022 SOUL SYNDICATE – DUB CLASSICS £ JR023 AUGUSTUS PABLO MEETS LEE PERRY/WAILERS £ JR024 RONNIE DAVIS – ‘JAMMIN IN DUB’ £ JR025 KING JAMMY’S DUB EXPLOSION £ JR026 PROFESSIONALS MEETS THE AGGRAVATORS AT JOE GIBBS £ JR027 DYNAMIC ‘DUBBING AT DYNAMIC SOUNDS’ £ JR028 DJ JAMAICA ‘INNA FINE DUB STYLE’ £ JR029 SCIENTIST - AT THE CONTROLS OF DUB ‘RARE DUBS 1979 - 1980’ £ JR030 JAMAICAN RECORDINGS ‘DUB SAMPLE VOL. -

Wavelength (December 1984)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 12-1984 Wavelength (December 1984) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (December 1984) 50 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/50 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF NEW ORLEANS EARL K LONG LIBRARY ACQUISITIONS DEPT NEW ORLEANS. LA 70148 1101 S.PETERS PHVSALIA PRODUCTION PRESENTATION NOONE UNOER18 ADMITTED ISSUE NO. 50 e DECEMBER 1984 "''m not sure, but I'm almost she1o's positive, that all music came from New Orleans." -Ernie K-Doe, 1979 D EPARTMENTS LIVE BANDS EVERY December News .... .... .. .. ... 4 Golden Moments . ........... ..... 8 NIGHT OF THE WEEK Flip City . ......... ............. 8 (NO COVER EVER!!!) New Bands ....... ..... .. ... 10 Caribbean . .. .. ........ ... .. .. 12 ENTRANCE ON SOUTH PETERS BETWEEN JULIA & ST. JOSEPH Dinette Set . ......... ............ 14 Rare Record . .. .... .. .. ... ... 16 Reviews . .. ...... ..... ... ... 16 shei Ia's features local, national, Listings . .. ........... .. .. .. 23 and international groups such as ... Last Page . ....................... 30 FEATURES Number 50 . 19 Dear Santa .. .... .. .. .. .. 22 Lady Rae New Orleans 1984 .... .. .. .. ... 25 Neville Brothers The Cold Records .. ........ ... .. ...... 31 One-Stops . .. .. ..... .. .. .. 35 Radia!ors HooDoo Guru's Hanoi Rocks Tim Shaw Cover design by Steve St. Germam. For informa Belfegore Java tion on purchasing cover art, ca/1 504/895-2342. John Fred & The Playboys Mrolberof f Habit JD & The Jammers Force o . -

WAR GAMES Any Genre Is Somewhat of a Damocles Sword

OFF THE FLOOR OFF THE FLOOR Books, art, movies, etc... Words: KIRSTY ALLISON as anonymous gate-holders to all things trip-hop. much observers of the culture around them as art WAR GAMES Any genre is somewhat of a Damocles sword. The makers. So this feeds into a rich loop of creativity. This new Massive Attack book is well group’s continuing sonic warfare mirrors Bristol’s “Adam Curtis is a BBC documentary film-maker worth investigating... port, bashing with all the waves of the world’s who has challenged television quite deeply. They tides, from slavery to silks, spices and the roots/ first worked together for the 2013 Manchester history of St Pauls. We speak to Melissa Chemam, International Festival. Curtis called it a ‘gilm’: whose encyclopaedic new book Out Of The Comfort gig + film. I’m not sure it fits. The visuals and the Zone has just been translated into English from music create something very special, but it is an her French original. additional layer and, much as Curtis’ messages “For me, Massive Attack are a living organism,” are powerful, overall, it only works because it’s Chemam says. “They emerged as a collective in Massive Attack.” 1988, with 3D, Daddy G and Mushroom, but the group wouldn’t be complete without their guest Punk was an influence on Massive Attack, vocalists. First came Horace Andy, Shara Nelson you say in the book: “In 1980, Bristol was and rapper Tricky. But the latter two left, so particularly sensitive to tensions. On 2nd suddenly the ever-evolving collective became not April, riots erupted in St Pauls, when the police only a concept, but a trademark. -

United Reggae Magazine #7

MAGAZINE #12 - October 2011 Queen Ifrica INTERVIEW FRANZ JOB SOLO BANTON DAWEH CONGO JOHNNY CLARKE JUNIOR MURVIN DON CORLEON, PRESSURE AND PROTOJE Sugar Minott - Dennis Brown - Peter Tosh - Tony Rebel J-Boog - Ce’Cile - Ruff Scott - I-Wayne - Yabass - Raging Fyah Bunny Lee and The Agrovators - Sly and Robbie - Junior Reid United Reggae Magazine #12 - October 2011 Want to read United Reggae as a paper magazine? Now you can... In addition to the latest United Reggae news, views and videos online each month you can now enjoy a SUMMARY free pdf version packed with most of United Reggae content from the last month. 1/ NEWS EDITORIAL by Erik Magni 2/ INTERVIEWS • Don Corleon, Pressure and Protoje 16 • Solo Banton 18 • Johnny Clarke 23 • Daweh Congo 25 • Queen Ifrica 29 • Franz Job 32 • Junior Murvin 35 3/ REVIEWS • The Upsessions - Below The Belt 41 • J-Boog - Backyard Boogie 42 • CeCile - Jamaicanization 44 Discover new music • Ruff Scott - Roots And Culture 45 • I-Wayne - Life Teachings 46 In the heydays of music magazines in the 90’s and early 2000’s getting a complimentary • Yabass - Back A Yard Dub 47 music CD was a regular pleasure. I for one found several new artists and groups due to • Bunny Lee and The Agrovators - Dub Will Change Your Mind 48 this promotional tool. Since then the music and publishing businesses have radically • Raging Fyah - Judgement Day 49 changed. Consumers have taken their reading and listening habits online and this has • The Bristol Reggae Explosion 2: The 1980s 50 lead to a dramatic decrease in sold physical units. -

STEVE HARNELL Catches up with Massive Attack's Robert Del Naja at the Band's Bristol Studios to Get the Lowdown on Their

4 www.thisisbristol.co.uk Thursday, February 4, 2010 Thursday, February 4, 2010 www.thisisbristol.co.uk 5 Music Food www.crackerjack.co.uk Warm chocolate STEVE HARNELL brownie at Review Hermanos catches up with Keeping Massive Attack’s Back on the Attack Hermanos Robert Del Naja at 55 Queens Road, Clifton, Bristol, Asia, Australia and New Zealand, the BS8 1QQ. Tel: 0117 9294323 States and Canada. South America, Massive Attack’s the band’s Bristol too. We’re even talking about going Grant “Daddy G” t was the soup that studios to get the back to the Middle East and Africa.” Marshall and Robert first caught my eye The new album sees Massive “3D” Del Naja I working with more collaborators when I walked past lowdown on their than ever before. It’s something of a it in the dream team of acclaimed vocalists Hermanos, a café bar on Clifton Triangle. which takes in Damon Albarn, much-anticipated Elbow’s Guy Garvey, former Mazzy The small menu in the window Star frontwoman Hope Sandoval, TV started with the words ‘Moro’s On The Radio’s Tunde Adebimpe, beetroot soup with black cumin’, new album a reference to a dish that appears former Tricky muse Martina at one of London’s best Heligoland Topley-Bird and the ever-present restaurants. reggae veteran Horace Andy. Great offer to And then, a few lines below it, “I’ve been banging on about I spotted ‘Homage to Stephen family making a Gothic soul album for years assive Attack have now but it just hasn’t happened. -

Articulation of Rastafarian Livity in Finnish Roots Reggae Sound System Performances

Listening to Intergalactic Sounds – Articulation of Rastafarian Livity in Finnish Roots Reggae Sound System Performances TUOMAS JÄRVENPÄÄ University of Eastern Finland Abstract: Rastafari is an Afro-Jamaican religious and social movement, which has since the 1970s spread outside of the Caribbean mainly through reggae music. This paper contributes to the academic discussion on the localization processes of Rastafari and reggae with an ethnographic account from the Nordic context, asking how Finnish reggae artists with Rastafarian conviction mobilize this identification in their per- formance. The paper focuses on one prominent Finnish reggae sound system group, Intergalaktik Sound. The author sees reggae in Finland as divided between contemporary musical innovation and the preservation of musical tradition. In this field, Intergalaktik Sound attempts to preserve what they consider to be the traditional Jamaican form of reggae sound system performance. For the Intergalaktik Sound vocalists, this specific form of perfor- mance becomes an enchanted space within a secular Finnish society, where otherwise marginal Rastafarian convictions can be acted out in public. The author connects the aesthetic of this performance to the Jamaican dub-music tradition, and to the concept of a ‘natural life’, which is a central spiritual concept for many Finnish Rastafarians. The article concludes that these sound system performances constitute a polycentric site where events can be experienced and articulated simultaneously as religious and secular by different individuals in the same space. Keywords: Rastafari, sound system, localization, re-enchantment, ethnography Reggae, in its various forms, has emerged during the past decade as one of the most visible and vibrant forms of Finnish popular music. -

The Snow Miser Song 6Ix Toys - Tomorrow's Children (Feat

(Sandy) Alex G - Brite Boy 1910 Fruitgum Company - Indian Giver 2 Live Jews - Shake Your Tuchas 45 Grave - The Snow Miser Song 6ix Toys - Tomorrow's Children (feat. MC Kwasi) 99 Posse;Alborosie;Mama Marjas - Curre curre guagliò still running A Brief View of the Hudson - Wisconsin Window Smasher A Certain Ratio - Lucinda A Place To Bury Strangers - Straight A Tribe Called Quest - After Hours Édith Piaf - Paris Ab-Soul;Danny Brown;Jhene Aiko - Terrorist Threats (feat. Danny Brown & Jhene Aiko) Abbey Lincoln - Lonely House - Remastered Abbey Lincoln - Mr. Tambourine Man Abner Jay - Woke Up This Morning ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE - Are We Experimental? Adolescents - Democracy Adrian Sherwood - No Dog Jazz Afro Latin Vintage Orchestra - Ayodegi Afrob;Telly Tellz;Asmarina Abraha - 808 Walza Afroman - I Wish You Would Roll A New Blunt Afternoons in Stereo - Kalakuta Republik Afu-Ra - Whirlwind Thru Cities Against Me! - Transgender Dysphoria Blues Aim;Qnc - The Force Al Jarreau - Boogie Down Alabama Shakes - Joe - Live From Austin City Limits Albert King - Laundromat Blues Alberta Cross - Old Man Chicago Alex Chilton - Boplexity Alex Chilton;Ben Vaughn;Alan Vega - Fat City Alexia;Aquilani A. - Uh La La La AlgoRythmik - Everybody Gets Funky Alice Russell - Humankind All Good Funk Alliance - In the Rain Allen Toussaint - Yes We Can Can Alvin Cash;The Registers - Doin' the Ali Shuffle Amadou & Mariam - Mon amour, ma chérie Ananda Shankar - Jumpin' Jack Flash Andrew Gold - Thank You For Being A Friend Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness - Brooklyn, You're -

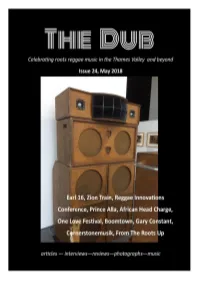

The Dub Issue 24 May 2018

1 BJ aka Ras Brother John Rest In Power 26 May 1960 - 28 March 2018 2 Editorial Dub Front cover – Heritage HiFi, built and restored by Dr Huxtable of Axis Sound System Dear Reader, Welcome to issue 24 for the month of Simeon. This month has been one of meeting many people, renewing old friendships and sadly saying goodbye to some no longer with us. The Dub this month is packed like never before. We have in depth interviews with Earl 16 and Zion Train’s Neil Perch, live reviews of Reading Dub Club and African Head Charge, coverage of April’s Reggae Innovations Conference in Birmingham, our regular features from Pete Clack and Cornerstonemusik as well as previews for the Boomtown and One Love Festivals later this year. We will have some of our team at both those festivals, so there should be reviews of some of the artists in issues yet to come. Salute as always to Marco Fregnan of Reggaediscography and Sista Mariana of Rastaites for keeping The Dub flowing. Welcome to The Dub Editor – Dan-I [email protected] The Dub is available to download for free at reggaediscography.blogspot.co.uk and rastaites.com The Dub magazine is not funded and has no sponsors. While this allows for artistic freedom, it also means that money for printing is very limited. If anyone is interested in printed copies, they should contact me directly and I can ask our printers, Parchment of Oxford, to get some of the issues required for the cost of £2.50 each. -

Speech Given at Afrika Eye Film Festival – 12 Nov 2016

SPEECH GIVEN AT AFRIKA EYE FILM FESTIVAL – 12 NOV 2016 Five Corners of Reggae: what reggae music means to me Dr Shawn-Naphtali Sobers Welcome to the Afrika Eye film festival screening of Roots, Reggae, Rebellion, the documentary on the history or reggae music presented by Akala. Today we are honoured to have Mykaell Riley from the legendary reggae band Steel Pulse with us, who features in the film. I’ll be interviewing Mykaell after the screening about his experience of Steel Pulse and what he’s doing now, in his new career as a scholar of music, an academic at the University of the Westminster, and please do ask him lots of questions. We also have a video message by the director of the film, James Hale, after this short introduction I have been asked to give, which I was honoured to accept. I’d like to share with you a personal exploration of reggae music means to me, especially in my formative teenage years, the impact it had on me and that I could see happening, and its significance across five aspects of life – which I call the Five Corners of Reggae Music. 1 - Cultural / Educational Music with a message of a proud Black African identity. Talking about the slavery in a way that was different to school, and singing names such as of Marcus Garvey and Haile Selassie, using words such as Sattamassagana, (an Amharic word meaning ‘give thanks and praises’). Infused with Biblical quotes and codes - roots reggae became like text-books for those of who were inspired by the music’s teaching and wanted to take it further.