Articulation of Rastafarian Livity in Finnish Roots Reggae Sound System Performances

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Rey Vallenato De La Academia Camilo Andrés Molina Luna Pontificia

EL REY VALLENATO DE LA ACADEMIA CAMILO ANDRÉS MOLINA LUNA PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD JAVERIANA FACULTAD DE ARTES TESIS DE PREGRADO BOGOTÁ D.C 2017 1 Tabla de contenido 1.Introducción ........................................................................................................ 3 2.Objetivos ............................................................................................................. 3 2.1.Objetivos generales ............................................................................................... 3 2.2.Objetivos específicos ............................................................................................ 3 3.Justificación ....................................................................................................... 4 4.Marco teórico ...................................................................................................... 4 5.Metodología y análisis ..................................................................................... 22 6.Conclusiones .................................................................................................... 32 2 1. Introducción A lo largo de mi carrera como músico estuve influenciado por ritmos populares de Colombia. Específicamente por el vallenato del cual aprendí y adquirí experiencia desde niño en los festivales vallenatos; eventos en los cuales se trata de rescatar la verdadera esencia de este género conformado por caja, guacharaca y acordeón. Siempre relacioné el vallenato con todas mis actividades musicales. La academia me dio -

Media and Advertising Information Why Advertise on Bigup Radio? Ranked in the Top 50,000 of All Sites According to Amazon’S Alexa Service

Media and Advertising Information Why Advertise on BigUp Radio? Ranked in the top 50,000 of all sites according to Amazon’s Alexa service Audience 16-34 year-old trend-setters and early adopters of new products. Our visitors purchase an average of $40–$50 each time they buy music on bigupradio.com and more than 30% of those consumers are repeat customers. Typical Traffic More than 1,000,000 unique page views per month Audience & Traffic 1.5 million tune-ins to the BigUp Radio stations Site Quick Facts Over 75,000 pod-cast downloads each month of BigUp Radio shows Our Stations Exclusive DJ Shows A Strong Image in the Industry Our Media Player BigUp Radio is in touch with the biggest artists on the scene as well as the Advertising Opportunities hottest upcoming new artists. Our A/R Dept listens to every CD that comes in selecting the very best tracks for airplay on our 7 stations. Among artists that Supporting Artists’ Rights have been on BigUp Radio for interviews and special guest appearances are: Rate Card Beenie Man Tanya Stephens Anthony B Contact Information: Lil Jon I Wayne TOK Kyle Russell Buju Banton Gyptian Luciano (617) 771.5119 Bushman Collie Buddz Tami Chynn [email protected] Cutty Ranks Mr. Vegas Delly Ranx Damian Marley Kevin Lyttle Gentleman Richie Spice Yami Bolo Sasha Da’Ville Twinkle Brothers Matisyahu Ziggi Freddie McGregor Jr. Reid Worldwide Reggae Music Available to anyone with an Internet connection. 7 Reggae Internet Radio Stations Dancehall, Roots, Dub, Ska, Lovers Rock, Soca and Reggaeton. -

Read Or Download

afrique.q 7/15/02 12:36 PM Page 2 The tree of life that is reggae music in all its forms is deeply spreading its roots back into Afri- ca, idealized, championed and longed for in so many reggae anthems. African dancehall artists may very well represent the most exciting (and least- r e c o g n i z e d ) m o vement happening in dancehall today. Africa is so huge, culturally rich and diverse that it is difficult to generalize about the musical happenings. Yet a recent musical sampling of the continent shows that dancehall is begin- ning to emerge as a powerful African musical form in its own right. FromFrom thethe MotherlandMotherland....Danc....Danc By Lisa Poliak daara-j Coming primarily out of West Africa, artists such as Gambia’s Rebellion D’Recaller, Dancehall Masters and Senegal’s Daara-J, Pee GAMBIA Froiss and V.I.B. are creating their own sounds growing from a fertile musical and cultural Gambia is Africa’s cross-pollination that blends elements of hip- dancehall hot spot. hop, reggae and African rhythms such as Out of Gambia, Rebel- Senegalese mbalax, for instance. Most of lion D’Recaller and these artists have not yet spread their wings Dancehall Masters are on the international scene, especially in the creating music that is U.S., but all have the musical and lyrical skills less rap-influenced to explode globally. Chanting down Babylon, than what is coming these African artists are inspired by their out of Senegal. In Jamaican predecessors while making music Gambia, they’re basi- that is uniquely their own, praising Jah, Allah cally heavier on the and historical spiritual leaders. -

Shilliam, Robbie. "Dread Love: Reggae, Rastafari, Redemption." the Black Pacific: Anti- Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections

Shilliam, Robbie. "Dread Love: Reggae, RasTafari, Redemption." The Black Pacific: Anti- Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015. 109–130. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 23 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474218788.ch-006>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 23 September 2021, 11:28 UTC. Copyright © Robbie Shilliam 2015. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Dread Love: Reggae, RasTafari, Redemption Introduction Over the last 40 years roots reggae music has been the key medium for the dissemination of the RasTafari message from Jamaica to the world. Aotearoa NZ is no exception to this trend wherein the direct action message that Bob Marley preached to ‘get up stand up’ supported the radical engagements in the public sphere prompted by Black Power.1 In many ways, Marley’s message and demeanour vindicated the radical oppositional strategies that activists had deployed against the Babylon system in contradistinction to the Te Aute Old Boy tradition of tactful engagement. No surprise, then, that roots reggae was sometimes met with consternation by elders, although much of the issue revolved specifically around the smoking of Marijuana, the wisdom weed.2 Yet some activists and gang members paid closer attention to the trans- mission, through the music, of a faith cultivated in the Caribbean, which professed Ethiopia as the root and Haile Selassie I as the agent of redemption. And they decided to make it their faith too. -

Chant Down Babylon: the Rastafarian Movement and Its Theodicy for the Suffering

Verge 5 Blatter 1 Chant Down Babylon: the Rastafarian Movement and Its Theodicy for the Suffering Emily Blatter The Rastafarian movement was born out of the Jamaican ghettos, where the descendents of slaves have continued to suffer from concentrated poverty, high unemployment, violent crime, and scarce opportunities for upward mobility. From its conception, the Rastafarian faith has provided hope to the disenfranchised, strengthening displaced Africans with the promise that Jah Rastafari is watching over them and that they will someday find relief in the promised land of Africa. In The Sacred Canopy , Peter Berger offers a sociological perspective on religion. Berger defines theodicy as an explanation for evil through religious legitimations and a way to maintain society by providing explanations for prevailing social inequalities. Berger explains that there exist both theodicies of happiness and theodicies of suffering. Certainly, the Rastafarian faith has provided a theodicy of suffering, providing followers with religious meaning in social inequality. Yet the Rastafarian faith challenges Berger’s notion of theodicy. Berger argues that theodicy is a form of society maintenance because it allows people to justify the existence of social evils rather than working to end them. The Rastafarian theodicy of suffering is unique in that it defies mainstream society; indeed, sociologist Charles Reavis Price labels the movement antisystemic, meaning that it confronts certain aspects of mainstream society and that it poses an alternative vision for society (9). The Rastas believe that the white man has constructed and legitimated a society that is oppressive to the black man. They call this society Babylon, and Rastas make every attempt to defy Babylon by refusing to live by the oppressors’ rules; hence, they wear their hair in dreads, smoke marijuana, and adhere to Marcus Garvey’s Ethiopianism. -

SS05 Naple Full Programme.Pdf

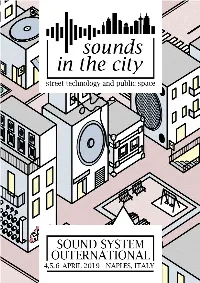

Across the globe the adaptation of Jamaican sound system culture has stimulated an innovative approach to sound technologies deployed to re-configure public spaces as sites for conviviality, celebration, resistance and different ways-of-knowing. In a world of digital social media, the shared, multi-sensory, social and embodied experience of the sound system session becomes ever more important and valuable. Sound System Outernational #5 – “Sounds in the City: Street Technology and Public Space” (4-5-6 April, 2019 - Naples, Italy) is designed as a multi-layered event hosted at Università degli Studi di Napoli L’Orientale with local social movement partners. Over three days and interacting with the city of Naples in its rich academic, social, political and musical dimensions, the event includes talks, roundtables, exhibitions and film screenings. It also features sound system dances hosting local and international performers in some of the city’s most iconic social spaces. The aim of the program is to provide the chance for foreign researchers to experience the local sound system scene in the grassroots venues that constitute this culture’s infrastructure in Naples. This aims to stimulate a fruitful exchange between the academic community and local practitioners, which has always been SSO’s main purpose. Sounds in the City will also provide the occasion for the SSO international research network meeting and the opportunity for a short-term research project on the Napoli sound system scene. Thursday, April 4th the warm-up session Thursday, April 4th “Warm Up Session” (16:30 to midnight) Venue: Palazzo Giusso, Università L’Orientale - Room 3.5 (Largo S. -

Jah Free 2016

JAH FREE 2016 THE DUB ACTIVIST The unique sounds of JAH FREE MUSIC seems to have no boundaries, he really can’t contain or control the movement of his music or where it will take him next. The people really do have the power and it is their love, vibes and support which keeps Jah Free Music very much alive and well today. The man himself never having had a plan, tries to take a natural musical path of progression, following the vibes and trying to always stand for the positive, his most important aim is to bring a ‘one love’ message in his musical works and live shows for anyone who cares to listen. Jah Free has been involved in the UK, European and now global reggae music scene for some 35 years with Roots, Dub, Digital productions and remixes. He first started out playing keys, percussion and singing in his band Tallowah back in the late to early 70s/80s, the band was formed by himself and his musically talented friends. The band’s name was later to become “Bushfire”, remembered by most as a highly successful UK Roots band for its time. Even now people mention those times and the live shows they enjoyed. Bushfire were asked to perform outside of the UK in Europe at festivals notably taking its own Wango Riley Stage on the road with its own mixing desk and P.A included, this being where Jah Free first learnt his many skills in live mixing. Worth mentioning that the Wango Rileys stage went on to become a very well known stage on the festival circuit over its many years, but sadly burnt down in the 90s. -

Rastalogy in Tarrus Riley's “Love Created I”

Rastalogy in Tarrus Riley’s “Love Created I” Darren J. N. Middleton Texas Christian University f art is the engine that powers religion’s vehicle, then reggae music is the 740hp V12 underneath the hood of I the Rastafari. Not all reggae music advances this movement’s message, which may best be seen as an anticolonial theo-psychology of black somebodiness, but much reggae does, and this is because the Honorable Robert Nesta Marley OM, aka Tuff Gong, took the message as well as the medium and left the Rastafari’s track marks throughout the world.1 Scholars have been analyzing such impressions for years, certainly since the melanoma-ravaged Marley transitioned on May 11, 1981 at age 36. Marley was gone too soon.2 And although “such a man cannot be erased from the mind,” as Jamaican Prime Minister Edward Seaga said at Marley’s funeral, less sanguine critics left others thinking that Marley’s demise caused reggae music’s engine to cough, splutter, and then die.3 Commentators were somewhat justified in this initial assessment. In the two decades after Marley’s tragic death, for example, reggae music appeared to abandon its roots, taking on a more synthesized feel, leading to electronic subgenres such as 1 This is the basic thesis of Carolyn Cooper, editor, Global Reggae (Kingston, Jamaica: Canoe Press, 2012). In addition, see Kevin Macdonald’s recent biopic, Marley (Los Angeles, CA: Magonlia Home Entertainment, 2012). DVD. 2 See, for example, Noel Leo Erskine, From Garvey to Marley: Rastafari Theology (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2004); Dean MacNeil, The Bible and Bob Marley: Half the Story Has Never Been Told (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2013); and, Roger Steffens, So Much Things to Say: The Oral History of Bob Marley, with an introduction by Linton Kwesi Johnson (New York and London: W.W. -

The Aura of Dubplate Specials in Finnish Reggae Sound System Culture

“Chase Sound Boys Out of Earth”: The Aura of Dubplate Specials in Finnish Reggae Sound System Culture Feature Article Kim Ramstedt Åbo Akademi University (Finland) Abstract This study seeks to expand our understanding of how dubplate specials are produced, circulated, and culturally valued in the international reggae sound system culture of the dub diaspora by analysing the production and performance of “Chase the Devil” (2005), a dubplate special commissioned by the Finnish MPV sound system from Jamaican reggae singer Max Romeo. A dubplate special is a unique recording where, typically, a reggae artist re-records the vocals to one of his or her popular songs with new lyrics that praise the sound system that commissioned the recording. Scholars have previously theorized dubplates using Walter Benjamin’s concept of aura, thereby drawing attention to the exclusivity and uniqueness of these traditionally analog recordings. However, since the advent of digital technologies in both recording and sound system performance, what Benjamin calls the “cult value” of producing and performing dubplates has become increasingly complex and multi-layered, as digital dubplates now remediate prior aesthetic forms of the analog. By turning to ethnographic accounts from the sound system’s DJ selectors, I investigate how digital dubplates are still culturally valued for their aura, even as the very concept of aura falls into question when applied to the recording and performance of digital dubplates. Keywords: aura, dubplate special, DJ, performance, reggae, recording, authenticity Kim Ramstedt is a PhD candidate in musicology at Åbo Akademi University in Finland. In his dissertation project, Ramstedt is studying DJs as cultural intermediaries and the localization of musical cultures through DJ practices. -

Créolité and Réunionese Maloya: from ‘In-Between’ to ‘Moorings’

Créolité and Réunionese Maloya: From ‘In-between’ to ‘Moorings’ Stephen Muecke, University of New South Wales An old Malbar is wandering in the countryside at night, and, seeing a light, approaches a cabin.1 It is open, so he goes in. He is invited to have a meal. No questions are asked; but he sings a ‘busted maloya’ [maloya kabosé] that speaks of his desire to open his wings and fly away, to accept the invitation to sleep in the cabin, to fall into the arms of the person narrating the ballad, and to weep. The whole company sings the ‘busted maloya.’2 Malbar is the name for Tamils descended from indentured labourers from parts of South India including the Malabar Coast and Pondicherry, where the French had another colony. Estimated to number 180,000, these diasporic Tamils had lost their language and taken up the local lingua franca, Creole, spoken among the Madagascans, French, Chinese and Africans making up the population of Réunion in the Indian Ocean. Creole, as a language and set of cultural forms, is not typical of many locations in the Indian Ocean. While the central islands of Mauritius, the Seychelles, Rodriguez, Agalega, Chagos and Réunion have their distinct varieties of French Creole language, Creole is not a concept that has currency in East Africa, Madagascar or South Asia. Versions of creolized English exist in Northern and Western Australia; at Roper River in the 1 Thanks to Elisabeth de Cambiaire and the anonymous reviewers of this paper for useful additions and comments, and to Françoise Vergès and Carpanin Marimoutou for making available the UNESCO Dossier de Candidature. -

LTB Portable Sound System P/N 051923 REV B Fender Musical Instruments 7975 North Hayden Road, Scottsdale, Arizona 85258 U.S.A

PORTABLE SOUND SYSTEMS From Fender Pro Audio Owner's Manual for LTB Portable Sound System P/N 051923 REV B Fender Musical Instruments 7975 North Hayden Road, Scottsdale, Arizona 85258 U.S.A. Fender knows the importance of sound reinforcement. From the simple box-top mixer to today's professional touring concert systems, the need to communicate, to make the connection between the performer and the audience is foremost in Fender's mind. Perhaps no other single piece of gear can make or break your band's sound. You see, your sound system is more than just a combination of dials, wires and speakers. It is an integral part of the audio chain and should be treated with special care and attention to detail. At Fender, we know what building quality musical instruments and sound reinforcement equipment is all about. In fact, many of the world's best sounding electric musical instruments and sound reinforcement equipment proudly wear the Fender name. Whether you need a simple box top powered mixer for your Saturday afternoon jam, or a professional full-size concert system, Fender has the sound reinforcement equipment to meet your needs. Likewise, your decision to purchase Fender pro audio gear is one you will appreciate with each performance for years to come. Wishing you years of enjoyment and a heartfelt thank you, Bill Schultz Bill Schultz Chairman Fender Musical Instruments Corporation THETHE FENDERFENDER LLTBTB PORTABLE POWERED MIXER INTRODUCTION 80 Watts into 4Ω The LTB: an 80 watt professional powered mixer from your friends at Fender® Pro Audio. We are sure you will find your new LTB sound system to be both 3-Band Equalizer a unique and effective sound reinforcement product, providing years of trouble-free service. -

The Spirit of Dancehall: Embodying a New Nomos in Jamaica Khytie K

The Spirit of Dancehall: embodying a new nomos in Jamaica Khytie K. Brown Transition, Issue 125, 2017, pp. 17-31 (Article) Published by Indiana University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/686008 Access provided by Harvard University (20 Feb 2018 17:21 GMT) The Spirit of Dancehall embodying a new nomos in Jamaica Khytie K. Brown As we approached the vicinity of the tent we heard the wailing voices, dominated by church women, singing old Jamaican spirituals. The heart beat riddim of the drums pulsed and reverberated, giving life to the chorus. “Alleluia!” “Praise God!” Indecipherable glossolalia punctu- ated the emphatic praise. The sounds were foreboding. Even at eleven years old, I held firmly to the disciplining of my body that my Catholic primary school so carefully cultivated. As people around me praised God and yelled obscenely in unknown tongues, giving their bodies over to the spirit in ecstatic dancing, marching, and rolling, it was imperative that I remained in control of my body. What if I too was suddenly overtaken by the spirit? It was par- ticularly disconcerting as I was not con- It was imperative that vinced that there was a qualitative difference between being “inna di spirit I remained in control [of God]” and possessed by other kinds of my body. What if of spirits. I too was suddenly In another ritual space, in the open air, lacking the shelter of a tent, heavy overtaken by the spirit? bass booms from sound boxes. The seis- mic tremors radiate from the center and can be felt early into the Kingston morning.