Versions, Dubs and Riddims: Dub and the Transient Dynamics of Jamaican Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dub Issue 15 August2017

AIRWAVES DUB GREEN FUTURES FESTIVAL RADIO + TuneIn Radio Thurs - 9-late - Cornerstone feat.Baps www.greenfuturesfestivals.org.uk/www.kingstongreenradi o.org.uk DESTINY RADIO 105.1FM www.destinyradio.uk FIRST WEDNESDAY of each month – 8-10pm – RIDDIM SHOW feat. Leo B. Strictly roots. Sat – 10-1am – Cornerstone feat.Baps Sun – 4-6pm – Sir Sambo Sound feat. King Lloyd, DJ Elvis and Jeni Dami Sun – 10-1am – DestaNation feat. Ras Hugo and Jah Sticks. Strictly roots. Wed – 10-midnight – Sir Sambo Sound NATURAL VIBEZ RADIO.COM Daddy Mark sessions Mon – 10-midnight Sun – 9-midday. Strictly roots. LOVERS ROCK RADIO.COM Mon - 10-midnight – Angela Grant aka Empress Vibez. Roots Reggae as well as lo Editorial Dub Dear Reader First comments, especially of gratitude, must go to Danny B of Soundworks and Nick Lokko of DAT Sound. First salute must go to them. When you read inside, you'll see why. May their days overflow with blessings. This will be the first issue available only online. But for those that want hard copies, contact Parchment Printers: £1 a copy! We've done well to have issued fourteen in hard copy, when you think that Fire! (of the Harlem Renaissance), Legitime Defense and Pan African were one issue publications - and Revue du Monde Noir was issued six times. We're lucky to have what they didn't have – the online link. So I salute again the support we have from Sista Mariana at Rastaites and Marco Fregnan of Reggaediscography. Another salute also to Ali Zion, for taking The Dub to Aylesbury (five venues) - and here, there and everywhere she goes. -

Angriff Der Melancholie Malen, Anti-Kriegs-Demos, Fußball: Für Musik Haben Die Einst So Coolen Futuristen Von Massive Attack Nur Noch Wenig Zeit

Angriff der Melancholie Malen, Anti-Kriegs-Demos, Fußball: Für Musik haben die einst so coolen Futuristen von Massive Attack nur noch wenig Zeit. VON CHRISTOPH DALLACH Dummerweise hat das neue Album jede nur mögliche Werbung nötig. Denn so hoch die Erwartungen an das einstige Pop-Avantgarde-Genie wa- rfolg im Pop ist auch immer eine Frage des ren, so bitter werden sie nun enttäuscht: neun Moll-Electro-Hop-Balladen, Timings. Und was das betrifft, hat das pa- die grau und bedeutungsschwanger ohne jeden Pep dahinwummern. Auch Ezifistische britische Musiker-Kollektiv, das die üblichen Gastsänger wie Reggae-Veteran Horace Andy und die kurz- sich ganz martialisch Massive Attack nennt, kei- haarige Heulsuse Sinéad O’Connor helfen da nichts mehr. ne glückliche Hand. Als Anfang der neunziger Der Aussetzer der Bristoler Elektro-Stars zeigt, wie schwierig es ist, im Mu- Jahre die erste Single seines Debüt-Albums ãBlue sikgeschäft über mehrere Jahre innovativ zu bleiben. Das ist umso trauri- Lines“ erschien, verscheuchten die Amerikaner ger, als es der ganzen Branche derzeit an Innovationen mangelt. Dabei gerade Saddam Hussein aus Kuweit. Die Musiker waren Massive Attack mal eine Institution, die Ma§stäbe für die moderne beschlossen, zeitweilig die Attacke aus ihrem Na- Popmusik gesetzt hat. Ende der achtziger Jahre, hervorgegangen aus der men zu streichen. HipHop-DJ-Künstler-Gang Wild Bunch in der britischen Hafenstadt Bristol, In diesem Monat erscheint mit ã100th Window“ hatten Massive Attack prägenden Anteil an der Entstehung des so genann- (Virgin) das vierte Werk von Massive Attack, wie- ten TripHop. Einem Sound, der von gebremsten HipHop-Beats und ge- der gibt’s Krach zwischen dem Chef der Iraker pflegter Melancholie bestimmt wurde und bis heute in Cafés, Clubs und und den Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika, und Boutiquen nachhallt. -

Read Or Download

afrique.q 7/15/02 12:36 PM Page 2 The tree of life that is reggae music in all its forms is deeply spreading its roots back into Afri- ca, idealized, championed and longed for in so many reggae anthems. African dancehall artists may very well represent the most exciting (and least- r e c o g n i z e d ) m o vement happening in dancehall today. Africa is so huge, culturally rich and diverse that it is difficult to generalize about the musical happenings. Yet a recent musical sampling of the continent shows that dancehall is begin- ning to emerge as a powerful African musical form in its own right. FromFrom thethe MotherlandMotherland....Danc....Danc By Lisa Poliak daara-j Coming primarily out of West Africa, artists such as Gambia’s Rebellion D’Recaller, Dancehall Masters and Senegal’s Daara-J, Pee GAMBIA Froiss and V.I.B. are creating their own sounds growing from a fertile musical and cultural Gambia is Africa’s cross-pollination that blends elements of hip- dancehall hot spot. hop, reggae and African rhythms such as Out of Gambia, Rebel- Senegalese mbalax, for instance. Most of lion D’Recaller and these artists have not yet spread their wings Dancehall Masters are on the international scene, especially in the creating music that is U.S., but all have the musical and lyrical skills less rap-influenced to explode globally. Chanting down Babylon, than what is coming these African artists are inspired by their out of Senegal. In Jamaican predecessors while making music Gambia, they’re basi- that is uniquely their own, praising Jah, Allah cally heavier on the and historical spiritual leaders. -

Linton Kwesi Johnson: Poetry Down a Reggae Wire

LINTON KWESI JOHNSON: POETRY DOWN A REGGAE WIRE by Robert J. Stewart for "Poetry, Motion, and Praxis: Caribbean Writers" panel XVllth Annual Conference CARIBBEAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION St. George's, Grenada 26-29 May, 1992 LINTON KWESI JOHNSON: POETRY DOWN fl RE66flE WIRE Linton Kwesi Johnson had been writing seriously for about four years when his first published poem appeared in 1973. There had been nothing particularly propitious in his experience up to then to indicate that within a relatively short period of time he would become an internationally recognized writer and performer. Now, at thirty-nine years of age, he has published four books of poetry, has recorded seven collections of his poems set to music, and has appeared in public readings and performances of his work in at least twenty-one countries outside of England. He has also pursued a parallel career as a political activist and journalist. Johnson was born in Chapelton in the parish of Clarendon on the island of Jamaica in August 1952. His parents had moved down from the mountains to try for a financially better life in the town. They moved to Kingston when Johnson was about seven years old, leaving him with his grandmother at Sandy River, at the foot of the Bull Head Mountains. He was moved from Chapelton All-Age School to Staceyville All-Age, near Sandy River. His mother soon left Kingston for England, and in 1963, at the age of eleven, Linton emigrated to join her on Acre Lane in Brixton, South London.1 The images of black and white Britain immediately impressed young Johnson. -

Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-18-2007 Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984 Caree Banton University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Banton, Caree, "Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984" (2007). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 508. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/508 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974 – 1984 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History By Caree Ann-Marie Banton B.A. Grambling State University 2005 B.P.A Grambling State University 2005 May 2007 Acknowledgement I would like to thank all the people that facilitated the completion of this work. -

The Performance of Accents in the Work of Linton Kwesi Johnson and Lemn Sissay

Thamyris/Intersecting No. 14 (2007) 51-68 “Here to Stay”: The Performance of Accents in the Work of Linton Kwesi Johnson and Lemn Sissay Cornelia Gräbner Introduction In his study Accented Cinema, Hamid Naficy uses the term “accent” to designate a new cinematic genre. This genre, which includes diasporic, ethnic and exilic films, is char- acterized by a specific “accented” style. In his analysis of “accented style,” Naficy broad- ens the term “accent” to refer not only to speech but also to “the film’s deep structure: its narrative visual style, characters, subject matter, theme, and plot” (Naficy 23). Thus, the term “accent” describes an audible characteristic of speech but can also be applied to describe many characteristics of artistic products that originate in a par- ticular community. “Accented films” reflect the dislocation of their authors through migration or exile. According to Naficy, the filmmakers operate “in the interstices of cultures and film practices” (4). Thus, Naficy argues, “accented films are interstitial because they are created astride and in the interstices of social formations and cinematic practices” (4). Naficy’s use of the term interstice refers back to Homi Bhabha, who argues that cultural change originates in the interstices between different cultures. Interstices are the result of “the overlap and displacement of domains of difference” (Bhabha 2). In the interstice, “social differences are not simply given to experience through an already authenticated cultural tradition” (3). Thus, the development of alternative styles and models of cultures, and the questioning of the cultures that dominate the space outside the interstice is encouraged. -

The Dub June 2018

1 Spanners & Field Frequency Sound System, Reading Dub Club 12.5.18 2 Editorial Dub Front cover – Indigenous Resistance: Ethiopia Dub Journey II Dear Reader, Welcome to issue 25 for the month of Levi. This is our 3rd anniversary issue, Natty Mark founding the magazine in June 2016, launching it at the 1st Mikey Dread Festival near Witney (an event that is also 3 years old this year). This summer sees a major upsurge in events involving members of The Dub family – Natty HiFi, Jah Lambs & Lions, Makepeace Promotions, Zion Roots, Swindon Dub Club, Field Frequency Sound System, High Grade and more – hence the launch of the new Dub Diary Newsletter at sessions. The aim is to spread the word about forthcoming gigs and sessions across the region, pulling different promoters’ efforts together. Give thanks to the photographers who have allowed us to use their pictures of events this month. We welcome some new writers this month too – thanks you for stepping up Benjamin Ital and Eric Denham (whose West Indian Music Appreciation Society newsletter ran from 1966 to 1974 and then from 2014 onwards). Steve Mosco presents a major interview with U Brown from when they recorded an album together a few years ago. There is also an interview with Protoje, a conversation with Jah9 from April’s Reggae Innovations Conference, a feature on the Indigenous Resistance collective, and a feature on Augustus Pablo. Welcome to The Dub Editor – Dan-I [email protected] The Dub is available to download for free at reggaediscography.blogspot.co.uk and rastaites.com The Dub magazine is not funded and has no sponsors. -

Interview with Donovan Germain 25 Years Penthouse Records

Interview with Donovan Germain 25 Years Penthouse Records 02/19/2014 by Angus Taylor Jamaican super-producer Donovan Germain recently celebrated 25 years of his Penthouse label with the two-disc compilation Penthouse 25 on VP Records. But Germain’s contribution to reggae and dancehall actually spans closer to four decades since his beginnings at a record shop in New York. The word “Germane” means relevant or pertinent – something Donovan has tried to remain through his whole career - and certainly every reply in this discussion with Angus Taylor was on point. He was particularly on the money about the Reggae Grammy, saying what has long needed to be said when perennial complaining about the Grammy has become as comfortable and predictable as the awards themselves. How did you come to migrate to the USA in early 70s? My mother migrated earlier and I came and joined her in the States. I guess in the sixties it was for economic reasons. There weren’t as many jobs in Jamaica as there are today so people migrated to greener pastures. I had no choice. I was a foolish child, my mum wanted me to come so I had to come! What was New York like for reggae then? Very little reggae was being played in New York. Truth be told Ken Williams was a person who was very instrumental in the outbreak of the music in New York. Certain radio stations would play the music in the grave yard hours of the night. You could hear the music at half past one, two o’clock. -

The Spirit of Dancehall: Embodying a New Nomos in Jamaica Khytie K

The Spirit of Dancehall: embodying a new nomos in Jamaica Khytie K. Brown Transition, Issue 125, 2017, pp. 17-31 (Article) Published by Indiana University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/686008 Access provided by Harvard University (20 Feb 2018 17:21 GMT) The Spirit of Dancehall embodying a new nomos in Jamaica Khytie K. Brown As we approached the vicinity of the tent we heard the wailing voices, dominated by church women, singing old Jamaican spirituals. The heart beat riddim of the drums pulsed and reverberated, giving life to the chorus. “Alleluia!” “Praise God!” Indecipherable glossolalia punctu- ated the emphatic praise. The sounds were foreboding. Even at eleven years old, I held firmly to the disciplining of my body that my Catholic primary school so carefully cultivated. As people around me praised God and yelled obscenely in unknown tongues, giving their bodies over to the spirit in ecstatic dancing, marching, and rolling, it was imperative that I remained in control of my body. What if I too was suddenly overtaken by the spirit? It was par- ticularly disconcerting as I was not con- It was imperative that vinced that there was a qualitative difference between being “inna di spirit I remained in control [of God]” and possessed by other kinds of my body. What if of spirits. I too was suddenly In another ritual space, in the open air, lacking the shelter of a tent, heavy overtaken by the spirit? bass booms from sound boxes. The seis- mic tremors radiate from the center and can be felt early into the Kingston morning. -

Dennis Brown ARTIST: Dennis Brown TITLE: The

DATE March 27, 2003 e TO Vartan/Um Creative Services/Meire Murakami FROM Beth Stempel EXTENSION 5-6323 SUBJECT Dennis Brown COPIES Alice Bestler; Althea Ffrench; Amy Gardner; Andy McKaie; Andy Street; Anthony Hayes; Barry Korkin; Bill Levenson; Bob Croucher; Brian Alley; Bridgette Marasigan; Bruce Resnikoff; Calvin Smith; Carol Hendricks; Caroline Fisher; Cecilia Lopez; Charlie Katz; Cliff Feiman; Dana Licata; Dana Smart; Dawn Reynolds; [email protected]; Elliot Kendall; Elyssa Perez; Frank Dattoma; Frank Perez; Fumiko Wakabayashi; Giancarlo Sciama; Guillevermo Vega; Harry Weinger; Helena Riordan; Jane Komarov; Jason Pastori; Jeffrey Glixman; Jerry Stine; Jessica Connor; Jim Dobbe; JoAnn Frederick; Joe Black; John Gruhler; Jyl Forgey; Karen Sherlock; Kelly Martinez; Kerri Sullivan; Kim Henck; Kristen Burke; Laura Weigand; Lee Lodyga; Leonard Kunicki; Lori Froeling; Lorie Slater; Maggie Agard; Marcie Turner; Margaret Goldfarb; Mark Glithero; Mark Loewinger; Martin Wada; Melanie Crowe; Michael Kachko; Michelle Debique; Nancy Jangaard; Norma Wilder; Olly Lester; Patte Medina; Paul Reidy; Pete Hill; Ramon Galbert; Randy Williams; Robin Kirby; Ryan Gamsby; Ryan Null; Sarah Norris; Scott Ravine; Shelin Wing; Silvia Montello; Simon Edwards; Stacy Darrow; Stan Roche; Steve Heldt; Sujata Murthy; Todd Douglas; Todd Nakamine; Tracey Hoskin; Wendy Bolger; Wendy Tinder; Werner Wiens ARTIST: Dennis Brown TITLE: The Complete A&M Years CD #: B0000348-02 UPC #: 6 069 493 683-2 CD Logo: A&M Records & Chronicles Attached please find all necessary liner notes and credits for this package. Beth Dennis Brown – Complete A&M Years B0000348-02 1 12/01/19 11:49 AM Dennis Brown The Complete A&M Years (CD Booklet) Original liner notes from The Prophet Rides Again This album is dedicated to the Prophet Gad (Dr. -

The A-Z of Brent's Black Music History

THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY BASED ON KWAKU’S ‘BRENT BLACK MUSIC HISTORY PROJECT’ 2007 (BTWSC) CONTENTS 4 # is for... 6 A is for... 10 B is for... 14 C is for... 22 D is for... 29 E is for... 31 F is for... 34 G is for... 37 H is for... 39 I is for... 41 J is for... 45 K is for... 48 L is for... 53 M is for... 59 N is for... 61 O is for... 64 P is for... 68 R is for... 72 S is for... 78 T is for... 83 U is for... 85 V is for... 87 W is for... 89 Z is for... BRENT2020.CO.UK 2 THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY This A-Z is largely a republishing of Kwaku’s research for the ‘Brent Black Music History Project’ published by BTWSC in 2007. Kwaku’s work is a testament to Brent’s contribution to the evolution of British black music and the commercial infrastructure to support it. His research contained separate sections on labels, shops, artists, radio stations and sound systems. In this version we have amalgamated these into a single ‘encyclopedia’ and added entries that cover the period between 2007-2020. The process of gathering Brent’s musical heritage is an ongoing task - there are many incomplete entries and gaps. If you would like to add to, or alter, an entry please send an email to [email protected] 3 4 4 HERO An influential group made up of Dego and Mark Mac, who act as the creative force; Gus Lawrence and Ian Bardouille take care of business. -

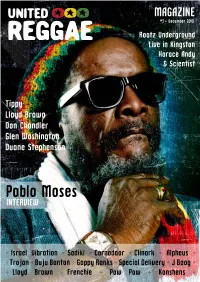

Pablo Moses INTERVIEW

MAGAZINE #3 - December 2010 Rootz Underground Live in Kingston Horace Andy & Scientist Tippy Lloyd Brown Don Chandler Glen Washington Duane Stephenson Pablo Moses INTERVIEW * Israel Vibration * Sadiki * Cornadoor * Clinark * Alpheus * * Trojan * Buju Banton * Gappy Ranks * Special Delivery * J Boog * * Lloyd Brown * Frenchie * Pow Pow * Konshens * United Reggae Mag #3 - December 2010 Want to read United Reggae as a paper magazine? In addition to the latest United Reggae news, views andNow videos you online can... each month you can now enjoy a free pdf version packed with most of United Reggae content from the last month.. SUMMARY 1/ NEWS •Lloyd Brown - Special Delivery - Own Mission Records - Calabash J Boog - Konshens - Trojan - Alpheus - Racer Riddim - Everlasting Riddim London International Ska Festival - Jamaican-roots.com - Buju Banton, Gappy Ranks, Irie Ites, Sadiki, Tiger Records 3 - 9 2/ INTERVIEWS •Interview: Tippy 11 •Interview: Pablo Moses 15 •Interview: Duane Stephenson 19 •Interview: Don Chandler 23 •Interview: Glen Washington 26 3/ REVIEWS •Voodoo Woman by Laurel Aitken 29 •Johnny Osbourne - Reggae Legend 30 •Cornerstone by Lloyd Brown 31 •Clinark - Tribute to Michael Jackson, A Legend and a Warrior •Without Restrictions by Cornadoor 32 •Keith Richards’ sublime Wingless Angels 33 •Reggae Knights by Israel Vibration 35 •Re-Birth by The Tamlins 36 •Jahdan Blakkamoore - Babylon Nightmare 37 4/ ARTICLES •Is reggae dying a slow death? 38 •Reggae Grammy is a Joke 39 •Meet Jah Turban 5/ PHOTOS •Summer Of Rootz 43 •Horace Andy and Scientist in Paris 49 •Red Strip Bold 2010 50 •Half Way Tree Live 52 All the articles in this magazine were previously published online on http://unitedreggae.com.This magazine is free for download at http://unitedreggae.com/magazine/.