The Archaeology of Folk and Official Religion During the High Middle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vega-Sicilia-DI-2018-Np.Pdf

www.vntgimports.com Vega Sicilia needs no introduction and is considered, by most, to be one of the top ten wineries in the world. They cater to a very select clientele in 85 countries, and even then only exports 40 percent of its limited production of 130,000 bottles a year. The other 60 percent is sold in Spain. The jewel in the winery’s crown, Vega Sicilia Unico, takes 10 years to produce. The Valbuena is not a second wine. Rather, it is a different expression that has aged for less time, and will drink sooner, than Unico. It is a wine that comes from the younger vines and, it is mostly made with the varieties of Tempranillo and Merlot, rather than Cabernet Sauvignon. Bodegas Alión was formed in 1986 as a winery which would be run independently to its big brother, the great Vega Sicilia. This 85-hectare wine estate was founded by the Álvarez family to provide a modern expression of Ribera del Duero wine. 35 hectares of the estate is located around the winery, with a further 50 hectares dedicated to Alión within the historic Vega Sicilia vineyards. Unlike Vega Sicilia, where we find a merging of the traditional and modern winemaking techniques, Alión is made using state-of-the-art equipment. Forward and uncompromising, these are wines with impressive frames and show an alternative side of Tinto Fino. Pintia realizes the desire of the Álvarez family to make the best Toro wine, a designation that gives wines body, exoticism, an explosion of aromas, and a modern personality and character. -

Diapositiva 1

Dossier de prensa Dossier de prensa Actividades y Fiestas 1. Akelarre. Dólmen de la Hechicera. Elvillar. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 2. Concierto. Iglesia de Yécora. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 3. Experiencia en viñedo. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 4. Fiesta de la Vendimia. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 5. Fiestas en Laguardia. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 6. Laguardia_noche. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 7. Lanciego. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 8. Lapuebla de Labarca. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 9. Mountain Bike. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 10. Tremolar de la bandera. Oyón-Oion. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 11. Pisando uvas. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Servicios Turísticos Thabuca Vino y Cultura 12. Yécora. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 13. Piraguas en el Ebro. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 14. 4X4 entre viñedos. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 15. Almuerzo entre viñedos. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 16. Pórtico de Laguardia. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 17. Envinando en Bodega. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas Dossier de prensa Actividades y Fiestas 1. Akelarre. Dólmen de 2. Concierto. Iglesia de 3. Experiencia en viñedo 4. Fiesta de la Vendimia 5. Fiestas en Laguardia. la Hechicera. Elvillar Yécora. 6. Laguardia_noche. 7. Lanciego. 8. Lapuebla de Labarca. 9. Mountain Bike. 10. Tremolar de la bandera. Oyón 11. Pisando uvas 14. 4X4 entre viñedos 13. Piraguas en el Ebro. -

Lunes, 6 De Septiembre De 1999 L B.O.T.H.A. Núm. 105 1999Ko Irailaren 6A, Astelehena L A.L.H.A.O

Lunes, 6 de septiembre de 1999 L B.O.T.H.A. Núm. 105 1999ko irailaren 6a, astelehena L A.L.H.A.O. 105. zk. 8.851 3.- TRAMITACION, PROCEDIMIENTO Y FORMA DE ADJU- 3.- IZAPIDETZA, PROZEDURA ETA ADJUDIKATZEKO DICACION: MODUA: a) Tramitación: Ordinaria. a) Izapidetza: ohikoa. b) Procedimiento: Abierto. b) Prozedura: irekia. c) Forma de Adjudicación: Concurso. c) Adjudikatzeko modua: lehiaketa. 4.- PRESUPUESTO BASE DE LICITACION: Importe total: 4.- LIZITAZIOAREN OINARRIZKO AURREKONTUA: zenbate- Hasta 12.000.000 pesetas. koa guztira: 12.000.000 pezeta arte. 5.- ADJUDICACION: 5.- ADJUDIKAZIOA: a) Fecha: 11 de mayo de 1999. a) Data: 1999ko maiatzaren 11a. b) Contratista: Consultoría, Formación y Servicios Informá- b) Kontrataria: Consultoría, Formación y Servicios Informá- ticos Lerk, S.L. ticos Lerk, S.L. c) Nacionalidad: Española. c) Nazionalitatea: espainiarra. d) Importe adjudicación: 9.083.398 pesetas. d) Adjudikazioaren zenbatekoa: 9.083.398 pezeta. e) Resolución de adjudicación: Orden Foral del Diputado e) Adjudikazioaren ebazpena: Foru eta Toki Administrazio Foral titular del Departamento de Administración Foral y Local eta Eskualde Garapenerako Saileko foru diputatu titularraren y Desarrollo Comarcal de la Diputación Foral de Alava número 250 zenbakidun Foru Agindua, 1999ko maiatzaren 11koa. 307 de 11 de mayo de 1999. Vitoria-Gasteiz, 25 de agosto de 1999.— La Directora de Eco- Vitoria/Gasteiz, 1999ko abuzutuaren 25a.— Ekonomia nomía, Mª TERESA CRESPO DEL CAMPO. Zuzendaria, Mª TERESA CRESPO DEL CAMPO. DEPARTAMENTO DE HACIENDA, OGASUN, -

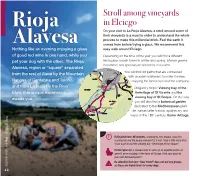

Rioja Alavesa, a Stroll Around Some of Their Vineyards Is a Must in Order to Understand the Whole Process to Make This Millennial Drink

Stroll among vineyards in Elciego Rioja On your visit to La Rioja Alavesa, a stroll around some of their vineyards is a must in order to understand the whole process to make this millennial drink. Feel the earth it Alavesa comes from before trying a glass. We recommend this Nothing like an evening enjoying a glass easy walk around Elciego. of good red wine in one hand, while you Depending on the time of the year you will find a different pet your dog with the other. The Rioja landscape: brown tones in winter and spring, intense greens in summer and spectacular red tones in autumn. Alavesa, region or “square” separated from the rest of Alava by the Mountain You will find dirt paths that are connected with wooden walkways to make it easier, Ranges of Cantabria and Toloño, enjoying the landscape and the company. and from La Rioja by the River Obligatory stops: Viewing bay of the Ebro, this unique experience Hermitage of St Vicente and the awaits you. viewing bay of St Roque. On the way you will also find abotanical garden dedicated to the Mediterranean plant life, named after historic apothecary and mayor in the 18th century, Xavier Arizaga. Rioja Alavesa ~ Estimated time: 45 minutes, stopping to take photos, enjoy the countryside and the peace and quiet (2.5 km). Save a little more time if you want to visit the viewing bay “Hermitage of San Roque”. Perfect plan for: a relaxed walk to work up an appetite before an with your dog aperitif, wine included, in the town of Elciego: clink your glass to your well-behaved pooch! Be attentive that your “best friend” does not eat any grapes, as these are highly toxic for many dogs. -

Cuadrilla De Laguardia- Rioja Alavesa 2020/2021 Laiaeskola Laguardia-Rioja Alavesa

Cuadrilla de Laguardia- Rioja Alavesa 2020/2021 www.laiaeskola.eus LAIAeskola Laguardia-Rioja Alavesa Información, contacto e inscripciones: Servicio de Igualdad de la Cuadrilla de Rioja Alavesa: 945 60 02 52 [email protected] Carretera Vitoria, 2. 01300 Laguardia, Álava Plazo para actividades con inscripción: hasta tres días antes del comien- zo del curso. Servicio de ludoteca y transporte: hasta tres días antes del comienzo de la actividad. Para estar al día, ¡apúntate al boletín digital mensual a través de la página web! Recibirás toda la información sobre actividades, recursos, actualidad y novedades. Las actividades presenciales se realizarán cumpliendo siempre las medi- das de prevención, seguridad e higiene recomendadas por el protocolo de actuación contra el COVID-19. @Laiaeskola @LaiaEskola @LaiaEskola www.laiaeskola.eus #LAIAeskolaArabakoErrioxa Secretaría Técnica de LAIAeskola: Berdintasun Proiektuak, S. Coop. www.berdintasun.org Portada e ilustración: Higi Vandis www.higinia.com Diseño y maquetación: La Debacle www.ladebacle.com Imprime: Diputación Foral Álava Para descargar descargar Para el folleto: D.L.: LG G 00483-2020 Índice LAIAeskola Laguardia-Rioja Alavesa 5 Un racimo de acciones para la igualdad en la Cuadrilla de Laguardia-Rioja Alavesa 6 Presentación de LAIAeskola y diálogo con Ángela Nzambi: “Las luchas de las mujeres en África” 8 Taller: Coaching y Liderazgo para mujeres de los Concejos de Álava 9 Club de Lectura Feminista “La Hora Violeta” en castellano 10 Club de Lectura Feminista en euskera -

Ruta Del Vino De Rioja Alavesa Dossier De Prensa Dossier De Prensa

Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa Dossier de Prensa Dossier de Prensa La Rioja Alavesa La Rioja Alavesa está situada al margen de la ribera del Ebro y desciende en laderas escalonadas desde la Sierra de Cantabria. Goza de un microclima privilegiado para el cultivo de la vid, una tradición que se remonta en Álava más allá de la época romana. La Cuadrilla de Rioja Laguardia-Rioja Alavesa está integrada por los municipios de Baños de Ebro-Mañueta, Kripán, Elciego, Elvillar-Bilar, Labastida-Bastida, Laguardia, Lanciego-Lantziego, Lapuebla de Labarca, Leza, Moreda de Álava, Navaridas, Oyón-Oion, Samaniego, Villabuena de Álava-Eskuernaga y Yécora-Ekora. Estos pueblos, vinculados tradicionalmente a la cultura del vino, conservan aún el encanto de las villas medievales levantadas entre viñedos y atesoran un vasto patrimonio natural, arqueológico y artístico. 2 Dossier de Prensa Los vinos de Rioja Alavesa La Rioja Alavesa cuenta con 12.000 hectáreas de viñedos. Sus vinos - elaborados dentro del marco de control del Consejo Regulador de la Denominación de Origen Calificada Rioja- gozan de un merecido prestigio internacional. La calidad de sus caldos se debe, en gran medida, al suelo arcillo- calcáreo (excelente para que las cepas absorban la humedad necesaria), al clima y a la ubicación de los viñedos tras la Sierra Cantabria (que protege las viñas de los vientos fríos del Norte y permite que la cepa aproveche mejor el calor), así como al cuidado de sus gentes en conjugar el legado histórico de elaboración y las nuevas tecnologías. En Rioja Alavesa el visitante puede degustar desde caldos elaborados en cuevas medievales hasta vinos obtenidos en las instalaciones más vanguardistas del momento. -

Discover Rioja Alavesa Through…

EN FR DISCOVER RIOJA ALAVESA DÉCOUVREZ LA RIOJA ALAVESA TAILOR-MADE TOURISM TOURISM OFFICES LET US GUIDE YOU! TOURISME À LA CARTE OFFICES DU TOURISME LAISSEZ NOUS VOUS GUIDER DANS LA RIOJA ALAVESA TOURIST MAP OF ROUTE OF THE DOLMENS In addition to the guided tours offered by the tourist offices, in Rioja Alavesa there are also specialized services. In Labastida/Bastida specialized wine tourism travel agencies LA ROUTE DES DOLMENS can help you organise a bespoke trip. Thabuca Wine Tours and Riojaalavesaturismo. LAGUARDIA If you want to organize a trip to Rioja Alavesa, we can help you. We can provide you with com. In Laguardia there is Top Rioja agency too. our experience and know-how to prepare an “à la carte” trip, with personalized routes and RIOJA ALAVESA Something that characterizes Rioja Alavesa is its prehistoric remains. A total of eight Thanks to several specialized guides you can enjoy adventure, sport, nature, wine, oil Casa Garcetas. Mayor, 52 · T. 945 600 845 unique experiences so you can get to know, first hand, each corner and all the delights of dolmens at the foot of the flamboyant Toloño Mountain Range makes it an ideal route and gastronomy. Tour the region in a 4X4 vehicle, go rock climbing, hiking, kayaking E. [email protected] · W. www.laguardia-alava.com this land of wine. by car. They are among the largest and most spectacular dolmens in all the Basque and canoeing on the Ebro, SUP (Stand Up Paddle) boards, tour the region with an Country. Well-looked after and accessible, visitors will discover the magic they hide. -

Folleto Turismo Familiar

Piérdete por ÁLAVA Turismo Familiar Es un territorio que, pese a su pequeño tamaño, ofrece multitud de contrastes paisajísticos y de re- cursos turísticos diferentes, convirtiéndolo en un destino sumamente diverso y divertido para toda la familia. En el recorrido podréis apreciar detalles de la iden- tidad vasca, folklore, artesanía y la reconocida gas- tronomía, o visitar numerosos museos históricos o de arte contemporáneo que os posicionarán en la historia de este pueblo. Podréis hacer senderismo por Parques Natura- les de gran belleza, o dar paseos en bici por las Vías Verdes; pararos a observar aves o pegaros un baño en las playas de interior categorizadas con bandera azul, por la calidad de sus aguas. Desde dólmenes perfectamente conservados, murallas medievales, iglesias de gran valor artís- tico pasando por edificios neoclásicos o de mo- derna construcción, se os mostrará un exquisito patrimonio que sorprende por su valor y diversi- dad histórica. Pero aún hay más, porque Araba-Álava es un territorio lleno de festividades y celebracio- nes con un carácter propio e indiscutible di- versión. Consulta tu agenda y si te coincide alguna de ellas, anímate a participar. Somos gente muy acogedora, ya lo veréis... Las • Llodio • Artziniega 7Cuadrillas Respaldiza • • Aramaio • Amurrio • Gujuli • Legutio • Murgia • Zalduondo Zuhatzu • • Alegría- • Araia • Villanueva Kuartango Dulantzi • Salvatierra de Valdegovía • Vitoria- • Nanclares Gasteiz • Salinas de la Oca de Añana Sobrón • • Maestu Rivabellosa • Berantevilla • • Sta. Cruz de • Peñacerrada Campezo • Urturi • Labastida Ayala/Aiara • Laguardia Añana Campezo-Montaña Alavesa / Kanpezu-Arabako Mendialdea • Oyón-Oion Laguardia-Rioja Alavesa / Guardia-Arabako Errioxa Llanada Alavesa / Arabako Lautada Gorbeialdea Vitoria-Gasteiz Ayala / Aiara Cañón de Delika Mirador y Salto del Nervión Salburua Sierra Salvada Parque Goikomendi -Kuxkumendi Paseo entre los viñedos del Txakolí Bosque solidario Añana Parque Natural de Valderejo Camino de Santiago en familia Jardín Botánico de Sta. -

Ruta Medieval En Álava R1

Ruta medieval en Álava R1 Rutas entre Artziniega y Laguardia, que comparten cultura e historia: cascos medievales muy bien conservados, torres y murallas defensivas, y viñedos que se transforman en grandes vinos. Ruta medieval en Álava R1 Mi viaje Laguardia Conjunto histórico Laguardia Iglesia de Santa María de los Reyes Torre Abacial de Laguardia Estanque celtibérico de Laguardia Salinillas de Buradón Murallas de Salinillas de Buradón Salinas de Añana Valle Salado de Salinas de Añana Jardín Botánico de Santa Catalina Vitoria-Gasteiz Ciudad de Vitoria-Gasteiz Catedral de Santa María Visitas guiadas a la Catedral de Santa María Torre de Los Anda Palacio Bendaña Casa del Cordón Iglesia de San Miguel Arcángel Iglesia de San Pedro Apóstol Los Arquillos Oficina Municipal de Turismo de Vitoria-Gasteiz Santuario de Nuestra Señora de Estíbaliz Quejana Conjunto monumental de Quejana Palacio de los Ayala Museo de Arte Sacro de Quejana Oficina de Turismo de Quejana Artziniega Casco Medieval de Artziniega Santuario de Nuestra Señora de la Encina Museo Etnográfico de Artziniega Museo Taller Santxotena Oficina de Turismo de Artziniega Laguardia Conjunto histórico Laguardia Lugar de interés, Conjunto histórico Laguardia está situada al sur del territorio histórico de Álava y ocupa un lugar privilegiado dentro de Rioja Alavesa. Su ubicación en el centro de esta comarca responde al talante guerrero de su fundador y la misión defensiva que los reyes de Navarra encargaron a la villa, denominándola inicialmente con el nombre de “La Guarda de Navarra”. Laguardia, Álava, España +34945600845 http://www.laguardia-alava.com [email protected] Cómo llegar Ayuntamiento Laguardia Laguardia Iglesia de Santa María de los Reyes Lugar de interés, Arquitectura religiosa La iglesia de Santa María de los Reyes, situada en la zona norte de Laguardia, comenzó a construirse a finales del siglo XII en estilo románico. -

THE BASQUE COUNTRY a Varied and San Sebastián Seductive Region

1 Bilbao San Sebastián Vitoria-Gasteiz All of the TOP experiences detailed in TOP in this catalogue are subject to change and EXPE may be updated. Therefore, we advise you RIEN to check the website for the most up to date CE prices before you book your trip. www.basquecountrytourism.net 22 14 32 40 City break getaways 6 6 Bilbao 14 San Sebastián 22 Vitoria-Gasteiz 32 Gastronomy 40 Wine Tourism 44 50 44 The Basque Coast 50 Active Nature 56 Culture 60 Unmissable experiences 56 62 Practical information Bilbao San Sebastián Vitoria- Gasteiz 4 THE BASQUE COUNTRY a varied and San Sebastián seductive region You are about to embark on an adventure If you explore the history of the figures with many attractions: a varied landscape, who have marked the personality of these a mild climate, ancient culture, renowned communities, you will discover how their gastronomy... These are the nuances maritime, industrial and agricultural that make the Basque Country a tourist character, always diverse and enterprising, destination you will be delighted to has been bred. discover. And if you find the coastal and inland Two colours will accompany you on your villages interesting, you will be fascinated journey through the Basque Country: the by the three capitals. Bilbao will surprise green of the mountains and valleys, and you with its transformation from the blue of the sea. an industrial city to an avant garde metropolis, that brings together the You will discover that the Basque people world's best architects. San Sebastián, maintain strong links with the natural exquisite and unique, will seduce you with resources of the land and the sea. -

The City 12 Its Peculiar Almond Shape and the Remais of Allow Me to Offer You the Most Exquisite Dishes Have You Come with Children? 40 Its Walls, Awaits You

Plaza de España, 1 t. 945 16 15 98 f. 945 16 11 05 [email protected] www.vitoria-gasteiz.org/tourism turismo_vitoria Visitor’s turismovitoria GUIDE Certifications: Contributors: A small destination with Giant possibilities Published by: Congress and Tourism board. Employment and Sustainable Economic Development Department. Texts: Arbat, Miguel de Andrés. Design and layout: Line Recta, Creative Dream. Translated by: Traductores-Intérpretes GDS, S.L. Photographs: Erredehierro, Daniel Llano, Quintas fotógrafos, Javier Agote. Sinestesia Studios, Iosu Izarra, Creative dream, Jaizki Fontaneda. Printed by: Héctor Soluciones Gráficas. Edition: 8. Date: 3/2019 Welcome to Contents Vitoria-Gasteiz. We would like to do everything possible to festivals and shows for all tastes (from A bit of history 04 make your stay exceed you expectations. magicians and puppeteers to jazz or rock How to move around Vitoria-Gasteiz? 08 An almost thousand-year-old city that still music). preserves much of its medieval layout, with Discover the city 12 its peculiar almond shape and the remais of Allow me to offer you the most exquisite dishes Have you come with children? 40 its walls, awaits you. You will find a medieval that the gastronomy of Álava has to offer, Vitoria-Gasteiz, but one that is also Gothic, sophisticated recipes of the so-called new Would you like to go shopping? 42 Renaissance, neoclassical and modern. Basque cuisine and our famous pintxos. A Our cuisine 44 tip, everything will taste better if accompanied Would you like to go out tonight? 46 Vitoria-Gasteiz holds the sustainable tourism with a good wine from the Rioja Alavesa certification Biosphere, with the widest vineyards or a glass of txakoli. -

Ethnicity and Identity in a Basque Borderland, Rioja Alavesa, Spain

ETHNICITY AND IDENTITY IN A BASQUE BORDERLAND: RIOJA ALAVESA, SPAIN By BARBARA ANN HENDRY A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1991 Copyright 1991 by Barbara Ann Hendry ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The help of numerous individuals in Spain and the United States enabled me to complete this dissertation— it is difficult to adequately acknowledge them all in these few short pages. To begin, without the generous hospitality, friendship, and assistance of many people in Rioja and Rioja Alavesa in 1985 and 1987, this research would not have been possible. For purposes of confidentiality, I will not list individual names, but, thank all of those in Albelda de Iregua, San Vicente de la Sonsierra, Brihas, Elciego, Laguardia, and, especially, Lapuebla de Labarca, who graciously let me share in their lives. Friends in the city of Logroho were also supportive, especially Charo Cabezon and Julio Valcazar. Stephanie Berdofe shared her home during my first weeks in the field, and buoyed my spirits and allayed my doubts throughout the fieldwork. Carmelo Lison Tolosana welcomed me to Spain and introduced me to several of his students. Maribel Fociles Rubio and Jose Lison Areal discussed their respective studies of identity in Rioja and Huesca, and helped me to formulate the interview schedule I used in Rioja Alavesa. They, and Jose's wife. Pilar, provided much warm hospitality during several brief trips to Madrid. iii The government administrators I interviewed in Rioja Alavesa and Vitoria were cooperative and candid.