Ethnicity and Identity in a Basque Borderland, Rioja Alavesa, Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Connections Between Sámi and Basque Peoples

Connections between Sámi and Basque Peoples Kent Randell 2012 Siidastallan Outside of Minneapolis, Minneapolis Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota “D----- it Jim, I’m a librarian and an armchair anthropologist??” Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Connections between Sámi and Basque Peoples Hard evidence: - mtDNA - Uniqueness of language Other things may be surprising…. or not. It is fun to imagine other connections, understanding it is not scientific Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Documentary: Suddenly Sámi by Norway’s Ellen-Astri Lundby She receives her mtDNA test, and express surprise when her results state that she is connected to Spain. This also surprised me, and spurned my interest….. Then I ended up living in Boise, Idaho, the city with the largest concentration of Basque outside of Basque Country Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota What is mtDNA genealogy? The DNA of the Mitochondria in your cells. Cell energy, cell growth, cell signaling, etc. mtDNA – At Conception • The Egg cell Mitochondria’s DNA remains the same after conception. • Male does not contribute to the mtDNA • Therefore Mitochondrial mtDNA is the same as one’s mother. Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Four generation mtDNA line Sisters – Mother – Maternal Grandmother – Great-grandmother Jennie Mary Karjalainen b. Kent21 Randell March (c) 2012 1886, --- 2012 Siidastallan,parents from Kuusamo, Finland Linwood Township, Minnesota Isaac Abramson and Jennie Karjalainen wedding picture Isaac is from Northern Norway, Kvaen father and Saami mother from Haetta Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, village. -

How Can a Modern History of the Basque Country Make Sense? on Nation, Identity, and Territories in the Making of Spain

HOW CAN A MODERN HISTORY OF THE BASQUE COUNTRY MAKE SENSE? ON NATION, IDENTITY, AND TERRITORIES IN THE MAKING OF SPAIN JOSE M. PORTILLO VALDES Universidad del Pais Vasco Center for Basque Studies, University of Nevada (Reno) One of the more recurrent debates among Basque historians has to do with the very object of their primary concern. Since a Basque political body, real or imagined, has never existed before the end of the nineteenth century -and formally not until 1936- an «essentialist» question has permanently been hanging around the mind of any Basque historian: she might be writing the histo- ry of an non-existent subject. On the other hand, the heaviness of the «national dispute» between Basque and Spanish identities in the Spanish Basque territories has deeply determined the mean- ing of such a cardinal question. Denying the «other's» historicity is a very well known weapon in the hands of any nationalist dis- course and, conversely, claiming to have a millenary past behind one's shoulders, or being the bearer of a single people's history, is a must for any «national» history. Consequently, for those who consider the Spanish one as the true national identity and the Basque one just a secondary «decoration», the history of the Basque Country simply does not exist or it refers to the last six decades. On the other hand, for those Basques who deem the Spanish an imposed identity, Basque history is a sacred territory, the last refuge for the true identity. Although apparently uncontaminated by politics, Basque aca- demic historiography gently reproduces discourses based on na- - 53 - ESPANA CONTEMPORANEA tionalist assumptions. -

Vega-Sicilia-DI-2018-Np.Pdf

www.vntgimports.com Vega Sicilia needs no introduction and is considered, by most, to be one of the top ten wineries in the world. They cater to a very select clientele in 85 countries, and even then only exports 40 percent of its limited production of 130,000 bottles a year. The other 60 percent is sold in Spain. The jewel in the winery’s crown, Vega Sicilia Unico, takes 10 years to produce. The Valbuena is not a second wine. Rather, it is a different expression that has aged for less time, and will drink sooner, than Unico. It is a wine that comes from the younger vines and, it is mostly made with the varieties of Tempranillo and Merlot, rather than Cabernet Sauvignon. Bodegas Alión was formed in 1986 as a winery which would be run independently to its big brother, the great Vega Sicilia. This 85-hectare wine estate was founded by the Álvarez family to provide a modern expression of Ribera del Duero wine. 35 hectares of the estate is located around the winery, with a further 50 hectares dedicated to Alión within the historic Vega Sicilia vineyards. Unlike Vega Sicilia, where we find a merging of the traditional and modern winemaking techniques, Alión is made using state-of-the-art equipment. Forward and uncompromising, these are wines with impressive frames and show an alternative side of Tinto Fino. Pintia realizes the desire of the Álvarez family to make the best Toro wine, a designation that gives wines body, exoticism, an explosion of aromas, and a modern personality and character. -

Previous Studies

ABSTRACTS OF THE CONGRESS 1.- PREVIOUS STUDIES 1.1.- Multidisciplinary studies (historical, archaeological, etc.). 30 ANALYSIS AND PROPOSAL OF RENOVATION CRITERIA AT THE BUILDING HEADQUARTER OF THE PUBLIC WORKS REGIONAL MINISTER IN CASTELLÓN (GAY AND JIMÉNEZ, 1962) Martín Pachés, Alba; Serrano Lanzarote, Begoña; Fenollosa Forner, Ernesto ……...... 32 NEW CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE STUDY OF THE HERMITAGES SETTING AROUND CÁCERES Serrano Candela, Francisco ……...... 55 THE ORIENTATION OF THE ROMANESQUE CHURCHES OF VAL D’ARAN IN SPAIN (11TH-13TH CENTURIES) Josep Lluis i Ginovart; Mónica López Piquer ……...... 73 SANTO ANTÔNIO CONVENT IN IGARASSU, PE – REGISTER OF AN INTERVENTION Guzzo, Ana Maria Moraes; Nóbrega, Claudia ……...... 104 DONIBANE N134: HISTORICAL-CONSTRUCTIVE ANALYSIS OF LATE MEDIEVAL VILLAGE MANOR HOUSE IN PASAIA (GIPUZKOA - SPAIN) Luengas-Carreño, Daniel; Crespo de Antonio, Maite; Sánchez-Beitia, Santiago ……...... 126 CONSERVATION OF PREFABRICATED RESIDENTIAL HERITAGE OF THE CENTURY XX. JEAN PROUVÉ’S WORK Bueno-Pozo, Verónica; Ramos-Carranza, Amadeo ……...... 169 COMPARED ANALYSIS AS A CONSERVATION INSTRUMENT.THE CASE OF THE “MASSERIA DEL VETRANO” (ITALY) Pagliuca, Antonello; Trausi, Pier Pasquale ……...... 172 THE INTERRELATION BETWEEN ARCHITECTURAL CONCEPTION AND STRUCTURE OF THE DOM BOSCO SANCTUARY THROUGH THE RECOUPERATION OF ITS DESIGN Oliveira, Iberê P.; Brandão, Jéssica; Pantoja, João C.; Santoro, Aline M. C. ……...... 177 THE SILVER ROAD THROUGH COLONIAL CHRONICLES. TOOLS FOR THE ANALYSIS AND ENHANCEMENT OF HISTORIC LANDSCAPE Malvarez, María Florencia ……...... 202 ANTHROPIC TRANSFORMATIONS AND NATURAL DECAY IN URBAN HISTORIC AGGREGATES: ANALYSIS AND CRITERIA FOR CATANIA (ITALY) Alessandro Lo Faro; Angela Moschella; Angelo Salemi; Giulia Sanfilippo ……...... 216 THE BRICK BUILT FAÇADES OF TIERRA DE PINARES IN SEGOVIA. THE CASE OF PINARNEGRILLO Gustavo Arcones-Pascual; Santiago Bellido-Blanco; David Villanueva-Valentín-Gamazo; Alberto Arcones-Pascual ……..... -

Pais Vasco 2018

The País Vasco Maribel’s Guide to the Spanish Basque Country © Maribel’s Guides for the Sophisticated Traveler ™ August 2018 [email protected] Maribel’s Guides © Page !1 INDEX Planning Your Trip - Page 3 Navarra-Navarre - Page 77 Must Sees in the País Vasco - Page 6 • Dining in Navarra • Wine Touring in Navarra Lodging in the País Vasco - Page 7 The Urdaibai Biosphere Reserve - Page 84 Festivals in the País Vasco - Page 9 • Staying in the Urdaibai Visiting a Txakoli Vineyard - Page 12 • Festivals in the Urdaibai Basque Cider Country - Page 15 Gernika-Lomo - Page 93 San Sebastián-Donostia - Page 17 • Dining in Gernika • Exploring Donostia on your own • Excursions from Gernika • City Tours • The Eastern Coastal Drive • San Sebastián’s Beaches • Inland from Lekeitio • Cooking Schools and Classes • Your Western Coastal Excursion • Donostia’s Markets Bilbao - Page 108 • Sociedad Gastronómica • Sightseeing • Performing Arts • Pintxos Hopping • Doing The “Txikiteo” or “Poteo” • Dining In Bilbao • Dining in San Sebastián • Dining Outside Of Bilbao • Dining on Mondays in Donostia • Shopping Lodging in San Sebastián - Page 51 • Staying in Bilbao • On La Concha Beach • Staying outside Bilbao • Near La Concha Beach Excursions from Bilbao - Page 132 • In the Parte Vieja • A pretty drive inland to Elorrio & Axpe-Atxondo • In the heart of Donostia • Dining in the countryside • Near Zurriola Beach • To the beach • Near Ondarreta Beach • The Switzerland of the País Vasco • Renting an apartment in San Sebastián Vitoria-Gasteiz - Page 135 Coastal -

Spanish Censuses of the Sixteenth Century

BYU Family Historian Volume 1 Article 5 9-1-2002 Spanish Censuses of the Sixteenth Century George R. Ryskamp Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byufamilyhistorian Recommended Citation The BYU Family Historian, Vol. 1 (Fall 2002) p.14-22 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Family Historian by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Spanish Censuses of the Sixteenth Century by George R. Ryskamp, J.D., AG A genealogist tracing family lines backwards This article will be organized under a combination of in Spain will almost certainly find a lack of records the first and second approach, looking both at the that have sustained his research as he reaches the year nature of the original order to take the census and 1600. Most significantly, sacramental records in where it may be found, and identifying the type of about half ofthe parishes begin in or around the year census to be expected and the detail of its content. 1600, likely reflecting near universal acceptance and application of the order for the creation of baptismal Crown Censuses and marriage records contained in the decrees of the The Kings ofCastile ordered several censuses Council of Trent issued in 1563. 1 Depending upon taken during the years 1500 to 1599. Some survive the diocese between ten and thirty percent of only in statistical summaries; others in complete lists. 5 parishes have records that appear to have been In each case a royal decree ordered that local officials written in response to earlier reforms such as a (usually the municipal alcalde or the parish priest) similar decrees from the Synod of Toledo in 1497. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Memoria Del Trabajo Fin De Grado

MEMORIA DEL TRABAJO FIN DE GRADO ANÁLISIS ECONÓMICO Y FINANCIERO DE LAS BODEGAS DE VINO DE LA DENOMINACIÓN DE ORIGEN DE TACORONTE-ACENTEJO ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL ANALYSIS OF WINERY IN PROTECTED DESIGNATION OF ORIGIN IN TACORONTE-ACENTEJO Grado en Administración y Dirección de Empresas FACULTAD DE ECONOMÍA, EMPRESA Y TURISMO Curso Académico 2015 /2016 Autor: Dña. Bárbara María Morales Fariña Tutor: D. Juan José Díaz Hernández. San Cristóbal de La Laguna, a 3 de Marzo de 2016 1 VISTO BUENO DEL TUTOR D. Juan José Díaz Hernández del Departamento de Economía, Contabilidad y Finanzas CERTIFICA: Que la presente Memoria de Trabajo Fin de Grado en Administración y Dirección de Empresas titulada “Análisis Económico y Financiero de las bodegas de vino de la denominación de origen de Tacoronte-Acentejo” y presentada por la alumna Dña. Bárbara María Morales Fariña , realizada bajo mi dirección, reúne las condiciones exigidas por la Guía Académica de la asignatura para su defensa. Para que así conste y surta los efectos oportunos, firmo la presente en La Laguna a 3 de Marzo de dos mil dieciséis. El tutor Fdo: D. Juan José Díaz Hernández. San Cristóbal de La Laguna, a 3 de Marzo de 2016 2 ÍNDICE 1 INTRODUCCIÓN………………………………………………………………....5 2 EL SECTOR VINÍCOLA…………………………………………………….……6 2.1 El sector vinícola en Canarias………………………………………..….6 2.2 El sector del vino en la isla de Tenerife……………………………...…..8 2.3 Las denominaciones de origen en la isla de Tenerife…………………..10 2.4 La denominación de origen de Tacoronte-Acentejo………………........12 3 ESTUDIO ECONÓMICO -

Diapositiva 1

Dossier de prensa Dossier de prensa Actividades y Fiestas 1. Akelarre. Dólmen de la Hechicera. Elvillar. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 2. Concierto. Iglesia de Yécora. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 3. Experiencia en viñedo. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 4. Fiesta de la Vendimia. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 5. Fiestas en Laguardia. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 6. Laguardia_noche. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 7. Lanciego. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 8. Lapuebla de Labarca. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 9. Mountain Bike. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 10. Tremolar de la bandera. Oyón-Oion. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 11. Pisando uvas. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Servicios Turísticos Thabuca Vino y Cultura 12. Yécora. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 13. Piraguas en el Ebro. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 14. 4X4 entre viñedos. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 15. Almuerzo entre viñedos. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 16. Pórtico de Laguardia. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas 17. Envinando en Bodega. © Ruta del Vino de Rioja Alavesa / Quintas Dossier de prensa Actividades y Fiestas 1. Akelarre. Dólmen de 2. Concierto. Iglesia de 3. Experiencia en viñedo 4. Fiesta de la Vendimia 5. Fiestas en Laguardia. la Hechicera. Elvillar Yécora. 6. Laguardia_noche. 7. Lanciego. 8. Lapuebla de Labarca. 9. Mountain Bike. 10. Tremolar de la bandera. Oyón 11. Pisando uvas 14. 4X4 entre viñedos 13. Piraguas en el Ebro. -

Wine List Bolero Winery

WINE LIST BOLERO WINERY White & Rosé Wines Glass/Bottle* Red Wines Glass/Bottle* 101 2019 Albariño 10/32 108 2017 Garnacha 12/40 102 2018 Verdelho 10/32 110 NV Poco Rojo 12/32 103 2018 Garnacha Blanca 10/29 111 2019 Cabernet Sauvignon Reserve 20/80 104 2018 Libido Blanco 10/28 115 2004 Tesoro del Sol 12/50 50% Viognier, 50% Verdelho Zinfandel Port 105 2016 Muscat Canelli 10/24 116 2017 Monastrell 14/55 107 2018 Garnacha Rosa 10/25 117 2017 Tannat 12/42 109 Bolero Cava Brut 10/34 Signature Wine Flights Let's Cool Down Talk of the Town The Gods Must be Crazy Bolero Albariño Bolero Tannat 2016 Bodegas Alto Moncayo "Aquilon" Bolero Verdelho Bolero Monastrell 2017 Bodegas El Nido "El Nido" Bolero Libido Blanco Bolero Cabernet Sauvignon Reserve 2006 Bodegas Vega Sicilia "Unico" $18 $26 $150 Bizkaiko Txakolina is a Spanish Denominación de Origen BIZKAIKO TXAKOLINA (DO) ( Jatorrizko Deitura in Basque) for wines located in the province of Bizkaia, Basque Country, Spain. The DO includes vineyards from 82 different municipalities. White Wines 1001 2019 Txomin Etzaniz, Txakolina 48 1002 2019 Antxiola Getariako, Txakolina 39 Red Wine 1011 2018 Bernabeleva 36 Rosé Wine Camino de Navaherreros 1006 2019 Antxiola Rosé, 39 Getariako Hondarrabi Beltz 1007 2019 Ameztoi Txakolina, Rubentis Rosé 49 TERRA ALTA Terra Alta is a Catalan Denominación de Origen (DO) for wines located in the west of Catalonia, Spain. As the name indicates, Terra Alta means High Land. The area is in the mountains. White Wine Red Wine 1016 2018 Edetària 38 1021 2016 Edetària 94 Via Terra, Garnatxa Blanca Le Personal Garnacha Peluda 1017 2017 Edetària Selecció, Garnatxa Blanca 64 1022 2017 "Via Edetana" 90 1018 2017 Edetària Selecció, Garnatxa Blanca (1.5ml) 135 BIERZO Bierzo is a Spanish Denominación de Origen (DO) for wines located in the northwest of the province of León (Castile and León, Spain) and covers about 3,000 km. -

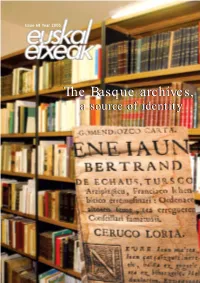

The Basquebasque Archives,Archives, Aa Sourcesource Ofof Identityidentity TABLE of CONTENTS

Issue 68 Year 2005 TheThe BasqueBasque archives,archives, aa sourcesource ofof identityidentity TABLE OF CONTENTS GAURKO GAIAK / CURRENT EVENTS: The Basque archives, a source of identity Issue 68 Year 3 • Josu Legarreta, Basque Director of Relations with Basque Communities. The BasqueThe archives,Basque 4 • An interview with Arantxa Arzamendi, a source of identity Director of the Basque Cultural Heritage Department 5 • The Basque archives can be consulted from any part of the planet 8 • Classification and digitalization of parish archives 9 • Gloria Totoricagüena: «Knowledge of a common historical past is essential to maintaining a people’s signs of identity» 12 • Urazandi, a project shining light on Basque emigration 14 • Basque periodicals published in Venezuela and Mexico Issue 68. Year 2005 ARTICLES 16 • The Basque "Y", a train on the move 18 • Nestor Basterretxea, sculptor. AUTHOR A return traveller Eusko Jaurlaritza-Kanpo Harremanetarako Idazkaritza 20 • Euskaditik: The Bishop of Bilbao, elected Nagusia President of the Spanish Episcopal Conference Basque Government-General 21 • Euskaditik: Election results Secretariat for Foreign Action 22 • Euskal gazteak munduan / Basque youth C/ Navarra, 2 around the world 01007 VITORIA-GASTEIZ Nestor Basterretxea Telephone: 945 01 7900 [email protected] DIRECTOR EUSKAL ETXEAK / ETXEZ ETXE Josu Legarreta Bilbao COORDINATION AND EDITORIAL 24 • Proliferation of programs in the USA OFFICE 26 • Argentina. An exhibition for the memory A. Zugasti (Kazeta5 Komunikazioa) 27 • Impressions of Argentina -

Comparing the Basque Diaspora

COMPARING THE BASQUE DIASPORA: Ethnonationalism, transnationalism and identity maintenance in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Peru, the United States of America, and Uruguay by Gloria Pilar Totoricagiiena Thesis submitted in partial requirement for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2000 1 UMI Number: U145019 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U145019 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Theses, F 7877 7S/^S| Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully acknowledge the supervision of Professor Brendan O’Leary, whose expertise in ethnonationalism attracted me to the LSE and whose careful comments guided me through the writing of this thesis; advising by Dr. Erik Ringmar at the LSE, and my indebtedness to mentor, Professor Gregory A. Raymond, specialist in international relations and conflict resolution at Boise State University, and his nearly twenty years of inspiration and faith in my academic abilities. Fellowships from the American Association of University Women, Euskal Fundazioa, and Eusko Jaurlaritza contributed to the financial requirements of this international travel.