How Can a Modern History of the Basque Country Make Sense? on Nation, Identity, and Territories in the Making of Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Connections Between Sámi and Basque Peoples

Connections between Sámi and Basque Peoples Kent Randell 2012 Siidastallan Outside of Minneapolis, Minneapolis Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota “D----- it Jim, I’m a librarian and an armchair anthropologist??” Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Connections between Sámi and Basque Peoples Hard evidence: - mtDNA - Uniqueness of language Other things may be surprising…. or not. It is fun to imagine other connections, understanding it is not scientific Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Documentary: Suddenly Sámi by Norway’s Ellen-Astri Lundby She receives her mtDNA test, and express surprise when her results state that she is connected to Spain. This also surprised me, and spurned my interest….. Then I ended up living in Boise, Idaho, the city with the largest concentration of Basque outside of Basque Country Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota What is mtDNA genealogy? The DNA of the Mitochondria in your cells. Cell energy, cell growth, cell signaling, etc. mtDNA – At Conception • The Egg cell Mitochondria’s DNA remains the same after conception. • Male does not contribute to the mtDNA • Therefore Mitochondrial mtDNA is the same as one’s mother. Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Four generation mtDNA line Sisters – Mother – Maternal Grandmother – Great-grandmother Jennie Mary Karjalainen b. Kent21 Randell March (c) 2012 1886, --- 2012 Siidastallan,parents from Kuusamo, Finland Linwood Township, Minnesota Isaac Abramson and Jennie Karjalainen wedding picture Isaac is from Northern Norway, Kvaen father and Saami mother from Haetta Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, village. -

Spanish Censuses of the Sixteenth Century

BYU Family Historian Volume 1 Article 5 9-1-2002 Spanish Censuses of the Sixteenth Century George R. Ryskamp Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byufamilyhistorian Recommended Citation The BYU Family Historian, Vol. 1 (Fall 2002) p.14-22 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Family Historian by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Spanish Censuses of the Sixteenth Century by George R. Ryskamp, J.D., AG A genealogist tracing family lines backwards This article will be organized under a combination of in Spain will almost certainly find a lack of records the first and second approach, looking both at the that have sustained his research as he reaches the year nature of the original order to take the census and 1600. Most significantly, sacramental records in where it may be found, and identifying the type of about half ofthe parishes begin in or around the year census to be expected and the detail of its content. 1600, likely reflecting near universal acceptance and application of the order for the creation of baptismal Crown Censuses and marriage records contained in the decrees of the The Kings ofCastile ordered several censuses Council of Trent issued in 1563. 1 Depending upon taken during the years 1500 to 1599. Some survive the diocese between ten and thirty percent of only in statistical summaries; others in complete lists. 5 parishes have records that appear to have been In each case a royal decree ordered that local officials written in response to earlier reforms such as a (usually the municipal alcalde or the parish priest) similar decrees from the Synod of Toledo in 1497. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor A Thesis in the Department of History Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts (History) at Concordia University Montréal, Québec, Canada March 2019 © Kyle McCreanor, 2019 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Kyle McCreanor Entitled: Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: _________________________________ Chair Dr. Andrew Ivaska _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Ted McCormick _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Cameron Watson _________________________________ Supervisor Dr. Gavin Foster Approved by _________________________________________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director _______________ 2019 _________________________________________ Dean of Faculty iii Abstract Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor This thesis examines the relationships between Irish and Basque nationalists and nationalisms from 1895 to 1939—a period of rapid, drastic change in both contexts. In the Basque Country, 1895 marked the birth of the Partido Nacionalista Vasco (Basque Nationalist Party), concurrent with the development of the cultural nationalist movement known as the ‘Gaelic revival’ in pre-revolutionary Ireland. In 1939, the Spanish Civil War ended with the destruction of the Spanish Second Republic, plunging Basque nationalism into decades of intense persecution. Conversely, at this same time, Irish nationalist aspirations were realized to an unprecedented degree during the ‘republicanization’ of the Irish Free State under Irish leader Éamon de Valera. -

Pathways out of Violence Desecuritization and Legalization of Bildu and Sortu in the Basque Country Bourne, Angela

Roskilde University Pathways out of violence Desecuritization and legalization of Bildu and Sortu in the Basque Country Bourne, Angela Published in: Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe Publication date: 2018 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Bourne, A. (2018). Pathways out of violence: Desecuritization and legalization of Bildu and Sortu in the Basque Country. Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe, 17(3), 45-66. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe Vol 17, No 3, 2018, 45-66. Copyright © ECMI 2018 This article is located at: http://www.ecmi.de/fileadmin/downloads/publications/JEMIE/201 8/Bourne.pdf Pathways out of Violence: Desecuritization and Legalization of Bildu and Sortu in the Basque Country Angela Bourne Roskilde University Abstract In this article, I examine political processes leading to the legalization of the Batasuna- successor parties, Bildu and Sortu. -

California's Legal Heritage

California’s Legal Heritage n the eve of California’s statehood, numerous Spanish Civil Law Tradition Odebates raged among the drafters of its consti- tution. One argument centered upon the proposed o understand the historic roots of the legal tradi- retention of civil law principles inherited from Spain Ttion that California brought with it to statehood and Mexico, which offered community property rights in 1850, we must go back to Visigothic Spain. The not conferred by the common law. Delegates for and Visigoths famously sacked Rome in 410 CE after years against the incorporation of civil law elements into of war, but then became allies of the Romans against California’s common law future used dramatic, fiery the Vandal and Suevian tribes. They were rewarded language to make their cases, with parties on both with the right to establish their kingdom in Roman sides taking opportunities to deride the “barbarous territories of Southern France (Gallia) and Spain (His- principles of the early ages.” Though invoked for dra- pania). By the late fifth century, the Visigoths achieved ma, such statements were surprisingly accurate. The complete independence from Rome, and King Euric civil law tradition in question was one that in fact de- established a code of law for the Visigothic nation. rived from the time when the Visigoths, one of the This was the first codification of Germanic customary so-called “barbarian” tribes, invaded and won Spanish law, but it also incorporated principles of Roman law. territory from a waning Roman Empire. This feat set Euric’s son and successor, Alaric, ordered a separate in motion a trajectory that would take the Spanish law code of law known as the Lex Romana Visigothorum from Europe to all parts of Spanish America, eventu- for the Hispanic Romans living under Visigothic rule. -

The Tubal Figure in Early Modern Iberian Historiography, 16Th and 17Th Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert THE TUBAL FIGURE IN EARLY MODERN IBERIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY, 16TH AND 17TH CENTURY MATTHIAS GLOËL UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DE TEMUCO CHILE Date of receipt: 16th of May, 2016 Final date of acceptance: 13th of September, 2016 ABSTRACT This study is dedicated to the use of the biblical figure Tubal in early modern Iberian chronicles. The focus will be centered on how it is used in different ways in the different kingdoms (Castile, Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia, Portugal and the Basque Provinces and Navarre) and what the authors are trying to achieve through this. Results show that while Castilian authors try to prove Spanish antiquity with the Tubal settlement, in other kingdom, especially in Catalonia, Portugal and Navarre there is a more regional use of the myth. Most of these authors try to prove that their own kingdom is the territory where Tubal settled, which would give a pre-eminence of antiquity to it in comparison to the other Iberian territories. KEYWORDS Early Modern History, Chronicles, Myths, Spanish Monarchy, Tubal. CapitaLIA VERBA Prima Historia Moderna, Chronica, Mythi, Monarchia Hispanica, Tubal. IMAGO TEMPORIS. MEDIUM AEVUM, XI (2017) 27-51 / ISSN 1888-3931 / DOI 10.21001/itma.2017.11.01 27 28 MATTHIAS GLOËL 1. Introduction Myths have always played an outstanding part in human history and they are without any doubt much older than science. This is also valid for chronicles or historiographical works. Christian historians in particular broke up the division between myth and history, which had been established by classical historiography.1 Only pagan stories remained myths, while the Bible gained the recognition of true history.2 Early Modern chronicles from the Iberian Peninsula are no exception to this phenomenon. -

Comparing the Basque Diaspora

COMPARING THE BASQUE DIASPORA: Ethnonationalism, transnationalism and identity maintenance in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Peru, the United States of America, and Uruguay by Gloria Pilar Totoricagiiena Thesis submitted in partial requirement for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2000 1 UMI Number: U145019 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U145019 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Theses, F 7877 7S/^S| Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully acknowledge the supervision of Professor Brendan O’Leary, whose expertise in ethnonationalism attracted me to the LSE and whose careful comments guided me through the writing of this thesis; advising by Dr. Erik Ringmar at the LSE, and my indebtedness to mentor, Professor Gregory A. Raymond, specialist in international relations and conflict resolution at Boise State University, and his nearly twenty years of inspiration and faith in my academic abilities. Fellowships from the American Association of University Women, Euskal Fundazioa, and Eusko Jaurlaritza contributed to the financial requirements of this international travel. -

The Effect of Franco in the Basque Nation

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses Summer 7-14-2011 The Effect of Franco in the Basque Nation Kalyna Macko Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Macko, Kalyna, "The Effect of Franco in the Basque Nation" (2011). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 68. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/68 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Macko 1 The Effect of Franco in the Basque Nation By: Kalyna Macko Pell Senior Thesis Primary Advisor: Dr. Jane Bethune Secondary Advisor: Dr. Clark Merrill Macko 2 Macko 3 Thesis Statement: The combined nationalist sentiments and opposition of these particular Basques to the Fascist regime of General Franco explained the violence of the terrorist group ETA both throughout his rule and into the twenty-first century. I. Introduction II. Basque Differences A. Basque Language B. Basque Race C. Conservative Political Philosophy III. The Formation of the PNV A. Sabino Arana y Goiri B. Re-Introduction of the Basque Culture C. The PNV as a Representation of the Basques IV. The Oppression of the Basques A. Targeting the Basques B. Primo de Rivera C. General Francisco Franco D. Bombing of Guernica E. -

Size Matters: the Values Behind Basque Food, Font and Semiotics

BOGA: Basque Studies Consortium Journal Volume 7 Issue 1 Article 3 October 2019 Size Matters: The Values Behind Basque Food, Font and Semiotics Kerri Lesh University of Nevada, Reno, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.boisestate.edu/boga Part of the Basque Studies Commons, Food Studies Commons, Linguistic Anthropology Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Lesh, Kerri (2019) "Size Matters: The Values Behind Basque Food, Font and Semiotics," BOGA: Basque Studies Consortium Journal: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. 10.18122/boga/vol7/iss1/3/boisestate Available at: https://scholarworks.boisestate.edu/boga/vol7/iss1/3 Size Matters: The Values Behind Basque Food, Font and Semiotics Cover Page Footnote A great thanks for the support of Cameron Watson and Daniel Montero in helping me revise this article. Additionally, I would like to thank everyone that was part of my fieldwork in the Basque Country and to my fellow panel members with whom this article was presented at the American Anthropological Association (AAA). This article is available in BOGA: Basque Studies Consortium Journal: https://scholarworks.boisestate.edu/boga/ vol7/iss1/3 Size Matters: The Values Behind Basque Food, Font and Semiotics Kerri Lesh, PhD. “People look for the origin of the wine they consume, they want to link it to the terroir … they are looking for something more than just the quality of the product, but rather the story behind the wine, the histories that lie behind a glass, and being able to focus in on a particular bodega, on the places where it is cultivated and produced. -

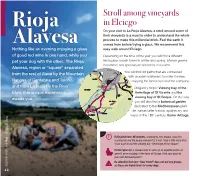

Rioja Alavesa, a Stroll Around Some of Their Vineyards Is a Must in Order to Understand the Whole Process to Make This Millennial Drink

Stroll among vineyards in Elciego Rioja On your visit to La Rioja Alavesa, a stroll around some of their vineyards is a must in order to understand the whole process to make this millennial drink. Feel the earth it Alavesa comes from before trying a glass. We recommend this Nothing like an evening enjoying a glass easy walk around Elciego. of good red wine in one hand, while you Depending on the time of the year you will find a different pet your dog with the other. The Rioja landscape: brown tones in winter and spring, intense greens in summer and spectacular red tones in autumn. Alavesa, region or “square” separated from the rest of Alava by the Mountain You will find dirt paths that are connected with wooden walkways to make it easier, Ranges of Cantabria and Toloño, enjoying the landscape and the company. and from La Rioja by the River Obligatory stops: Viewing bay of the Ebro, this unique experience Hermitage of St Vicente and the awaits you. viewing bay of St Roque. On the way you will also find abotanical garden dedicated to the Mediterranean plant life, named after historic apothecary and mayor in the 18th century, Xavier Arizaga. Rioja Alavesa ~ Estimated time: 45 minutes, stopping to take photos, enjoy the countryside and the peace and quiet (2.5 km). Save a little more time if you want to visit the viewing bay “Hermitage of San Roque”. Perfect plan for: a relaxed walk to work up an appetite before an with your dog aperitif, wine included, in the town of Elciego: clink your glass to your well-behaved pooch! Be attentive that your “best friend” does not eat any grapes, as these are highly toxic for many dogs. -

1 Centro Vasco New York

12 THE BASQUES OF NEW YORK: A Cosmopolitan Experience Gloria Totoricagüena With the collaboration of Emilia Sarriugarte Doyaga and Anna M. Renteria Aguirre TOTORICAGÜENA, Gloria The Basques of New York : a cosmopolitan experience / Gloria Totoricagüena ; with the collaboration of Emilia Sarriugarte Doyaga and Anna M. Renteria Aguirre. – 1ª ed. – Vitoria-Gasteiz : Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia = Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco, 2003 p. ; cm. – (Urazandi ; 12) ISBN 84-457-2012-0 1. Vascos-Nueva York. I. Sarriugarte Doyaga, Emilia. II. Renteria Aguirre, Anna M. III. Euskadi. Presidencia. IV. Título. V. Serie 9(1.460.15:747 Nueva York) Edición: 1.a junio 2003 Tirada: 750 ejemplares © Administración de la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco Presidencia del Gobierno Director de la colección: Josu Legarreta Bilbao Internet: www.euskadi.net Edita: Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia - Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco Donostia-San Sebastián, 1 - 01010 Vitoria-Gasteiz Diseño: Canaldirecto Fotocomposición: Elkar, S.COOP. Larrondo Beheko Etorbidea, Edif. 4 – 48180 LOIU (Bizkaia) Impresión: Elkar, S.COOP. ISBN: 84-457-2012-0 84-457-1914-9 D.L.: BI-1626/03 Nota: El Departamento editor de esta publicación no se responsabiliza de las opiniones vertidas a lo largo de las páginas de esta colección Index Aurkezpena / Presentation............................................................................... 10 Hitzaurrea / Preface.........................................................................................