ARTICLE Grand Strategizing in and For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SALNÂMELERE GÖRE ADANA VĠLÂYETĠ‟NĠN DEMOGRAFĠK VE KÜLTÜREL YAPISI (Adana Merkez, Kozan, Cebel-I Bereket, Ġçel Ve Mersin Sancağı)

T.C. Mersin Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Tarih Ana Bilim Dalı SALNÂMELERE GÖRE ADANA VĠLÂYETĠ‟NĠN DEMOGRAFĠK VE KÜLTÜREL YAPISI (Adana Merkez, Kozan, Cebel-i Bereket, Ġçel ve Mersin Sancağı) Sırma HASGÜL YÜKSEK LĠSANS TEZĠ Mersin, 2016 T.C. Mersin Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Tarih Ana Bilim Dalı SALNÂMELERE GÖRE ADANA VĠLÂYETĠ‟NĠN DEMOGRAFĠK VE KÜLTÜREL YAPISI (Adana Merkez, Kozan, Cebel-i Bereket, Ġçel ve Mersin Sancağı) Sırma HASGÜL DanıĢman Yrd. Doç. Dr. Ġbrahim BOZKURT YÜKSEK LĠSANS TEZĠ Haziran, 2016 i ÖNSÖZ Bu çalıĢmada, günümüzde Çukurova olarak adlandırılabilecek olan Adana Vilayeti‟nin, 1870-1902 yılları arasındaki durumu çeĢitli açılardan incelenmiĢtir. Adana Vilayeti‟nin bu dönemde içerisinde yaĢadığı idari, demografik ve kültürel değiĢim ve bu değiĢimlerin yansımaları bazen genel hatlarıyla bazen de kaza ve sancak bazında belirlenmeye çalıĢılmıĢtır. Bu çalıĢma konusunun belirlenmesi, belgelerin sağlanması ve tezin yürütülmesi sırasında hiçbir zaman yardımlarını esirgemeyen, ayrıca her zaman, her konuda bana yol gösteren ve destekleyen danıĢman hocam Yrd. Doç. Dr. Ġbrahim BOZKURT‟a teĢekkürlerimi sunarım. Ayrıca değerli önerilerinden ve teze katkılarından dolayı sayın Doç. Dr. ġenay ÖZDEMĠR GÜMÜġ‟e ve Yrd. Doç. Dr. Volkan PAYASLI‟ya teĢekkürlerimi sunmak isterim. Üniversitedeki eğitim hayatım süresince çalıĢmalarımda ve her türlü problemimde manevi desteğini ve yardımlarını hep yanımda hissettiğim değerli hocam Mehtap ERGENOĞLU‟na ve ilgilerinden dolayı tüm hocalarıma çok teĢekkür ederim. Tezde kullandığım -

Içel Sancaği'nin Yönetim Merkezi Olmak Için Kazalar

A. Ü. Türkiyat Araştırmaları Enstitüsü Dergisi [TAED] 56, ERZURUM 2016, 1215-1253 İÇEL SANCAĞI’NIN YÖNETİM MERKEZİ OLMAK İÇİN KAZALAR ARASINDA YAŞANAN MÜCADELE Ahmet Ali GAZEL Öz Karamanoğulları Beyliği’nin ortadan kaldırılmasıyla oluşturulan İçel Sancağı idarî olarak farklı eyaletlere bağlanmış ve son olarak 1869 yılında Adana Vilayeti’ne bağlanmıştır. 1915 yılında ise müstakil sancak haline dönüştürülmüştür. İçel Sancağı’nın bu isimle anılan bir merkezi olmadığı için sancak merkezi farklı tarihlerde farklı kazalar olmuştur. 1869’dan önce merkez Ermenek iken bu tarihte sancak Adana Vilayeti’ne bağlanınca vilayet merkezine yakınlığı sebebiyle sancak merkezi Silifke’ye alınmıştır. Ancak bu durum uzun zamandır sancak merkezliğini elinde bulunduran Ermeneklileri rahatsız etmiştir. Yapılan değişiklik Silifkelilerle Ermenekliler arasında 1919 yılına kadar sürecek hukuki ve siyasi bir mücadelenin de başlangıcı olmuştur. Ermenekliler değişik zamanlarda hükümet merkezine verdikleri arzuhallerde merkezin tekrar Ermenek’e alınmasını isterken Silifkeliler de birçok ekonomik ve coğrafi faktörü öne sürerek Silifke’de kalmasını istemişlerdir. Bildiride iki kazanın sancak merkezi olmak için verdikleri mücadele Osmanlı Arşivine dayalı olarak anlatılacaktır. Anahtar Sözcükler: İçel Sancağı, Ermenek, Silifke, Adana. THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN ERMENEK AND SILIFKE FOR BECOMING THE CAPITAL OF THE SANJAK OF ICEL Abstract The Sanjak of İçel, which was founded along with the destruction of Karamanids, was involved in several different principalities administratively and ultimately connected to the Province of Adana in 1869. In 1915, it became an independent sanjak. Because the Sanjak of İçel did not have the capital called İçel, different districts became its capitals on different dates. Before 1869, the capital was Ermenek while it was replaced by Silifke in 1869 when the sanjak was connected to the Province of Adana due to its geographic proximity to the provincial capital. -

Talaat Pasha's Report on the Armenian Genocide.Fm

Gomidas Institute Studies Series TALAAT PASHA’S REPORT ON THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE by Ara Sarafian Gomidas Institute London This work originally appeared as Talaat Pasha’s Report on the Armenian Genocide, 1917. It has been revised with some changes, including a new title. Published by Taderon Press by arrangement with the Gomidas Institute. © 2011 Ara Sarafian. All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-1-903656-66-2 Gomidas Institute 42 Blythe Rd. London W14 0HA United Kingdom Email: [email protected] CONTENTS Introduction by Ara Sarafian 5 Map 18 TALAAT PASHA’S 1917 REPORT Opening Summary Page: Data and Calculations 20 WESTERN PROVINCES (MAP) 22 Constantinople 23 Edirne vilayet 24 Chatalja mutasarriflik 25 Izmit mutasarriflik 26 Hudavendigar (Bursa) vilayet 27 Karesi mutasarriflik 28 Kala-i Sultaniye (Chanakkale) mutasarriflik 29 Eskishehir vilayet 30 Aydin vilayet 31 Kutahya mutasarriflik 32 Afyon Karahisar mutasarriflik 33 Konia vilayet 34 Menteshe mutasarriflik 35 Teke (Antalya) mutasarriflik 36 CENTRAL PROVINCES (MAP) 37 Ankara (Angora) vilayet 38 Bolu mutasarriflik 39 Kastamonu vilayet 40 Janik (Samsun) mutasarriflik 41 Nigde mutasarriflik 42 Kayseri mutasarriflik 43 Adana vilayet 44 Ichil mutasarriflik 45 EASTERN PROVINCES (MAP) 46 Sivas vilayet 47 Erzerum vilayet 48 Bitlis vilayet 49 4 Talaat Pasha’s Report on the Armenian Genocide Van vilayet 50 Trebizond vilayet 51 Mamuretulaziz (Elazig) vilayet 52 SOUTH EASTERN PROVINCES AND RESETTLEMENT ZONE (MAP) 53 Marash mutasarriflik 54 Aleppo (Halep) vilayet 55 Urfa mutasarriflik 56 Diyarbekir vilayet -

Catalogue: May #2

CATALOGUE: MAY #2 MOSTLY OTTOMAN EMPIRE, THE BALKANS, ARMENIA AND THE MIDDLE EAST - Books, Maps & Atlases 19th & 20th Centuries www.pahor.de 1. COSTUMES OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE A small, well made drawing represents six costumes of the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East. The numeration in the lower part indicates, that the drawing was perhaps made to accompany a Anon. [Probably European artist]. text. S.l., s.d. [Probably mid 19th century] Pencil and watercolour on paper (9,5 x 16,5 cm / 3.7 x 6.5 inches), with edges mounted on 220 EUR later thick paper (28 x 37,5 cm / 11 x 14,8 inches) with a hand-drawn margins (very good, minor foxing and staining). 2. GREECE Anon. [Probably a British traveller]. A well made drawing represents a Greek house, indicated with a title as a house between the port city Piraeus and nearby Athens, with men in local costumes and a man and two young girls in House Between Piraeus and Athens. central or west European clothing. S.l., s.d. [Probably mid 19th century]. The drawing was perhaps made by one of the British travellers, who more frequently visited Black ink on thick paper, image: 17 x 28 cm (6.7 x 11 inches), sheet: 27 x 38,5 cm (10.6 x 15.2 Greece in the period after Britain helped the country with its independence. inches), (minor staining in margins, otherwise in a good condition). 160 EUR 3. OTTOMAN GEOLOGICAL MAP OF TURKEY: Historical Context: The Rise of Turkey out of the Ottoman Ashes Damat KENAN & Ahmet Malik SAYAR (1892 - 1965). -

Adana Hamidiye Sanayi Mektebi Sultan Ii

USAD, Bahar 2019; (10): 179-202 E-ISSN: 2548-0154 SULTAN II. ABDÜLHAMİD’İN BİR YADİGÂRI: ADANA HAMİDİYE SANAYİ MEKTEBİ SULTAN II. ABDULHAMID'S ONE MEMENTO: ADANA HAMİDİYE INDUSTRY SCHOOL Ali Rıza GÖNÜLLÜ* Osmanlı Devletinde modern anlamda mesleki ve teknik eğitim konusunda çalışmalar Tanzimat’ın ilanından sonra başlamıştır. Ancak Mithat Paşa tarafından ıslahhanelerin kurulması ile mesleki ve teknik eğitim ülke genelinde yaygınlaşmaya başlamıştır. Mesleki ve teknik eğitim hizmetleri Sultan II. Abdülhamid döneminde önemli bir yoğunluk kazanmıştır. Bu dönemde Osmanlı ülkesinin muhtelif yerlerinde çeşitli mesleki ve teknik mektepler açılmıştır. Bunlar arasında erkek sanayi mektepleri de bulunuyordu. Sultan II. Abdülhamid Döneminde hizmete giren sanayi mekteplerinden birisi de Adana’da açılan Hamidiye Sanayi Mektebidir. Bu mektep Sultan II. Abdülhamid’in tahta geçişinin 25. Yıldönümü hatırasına, Adana Islahhanesinin, Adana Hamidiye Sanayi Mektebi haline dönüştürülmesi ile 22 Ağustos 1900 tarihinde eğitim faaliyetine başlamıştır. Bu mektebin hizmete girmesinde Adana Valiliğinin, mahalli halkın, Adana Ziraat ve Sanayi Odasının önemli katkıları olmuştur. Beş yıl süreli olan Adana Hamidiye Sanayi Mektebinin 6 Şubat 1901 tarihinde yıllara göre ders cetveli yayınlanmıştır. Bu ders cetveline göre kültür dersleri ile birlikte muhtelif dini dersler mektebin müfredat programında yer almıştır. Ayrıca bu mektepte yabancı dil olarak da Farsça, Arapça ve Fransızca öğretiliyordu. Teorik dersler için sabahları sanat öğretiminden evvel bir saat ve akşamları yemekten sonra iki saat tahsis edilmiştir. Adana Hamidiye Sanayi Mektebinin işleyişi, diğer bazı sanayi mektepleri gibi, Islahhaneler Nizamnamesinin hükümlerine göre tanzim edilmiştir. 1900 yılında Adana Hamidiye Sanayi Mektebinin mektep meclisi Ali Said Efendi’nin başkanlığında altı azadan meydana gelmiştir. Aynı yılmektebin * Dr. Alanya Mesleki ve Teknik Anadolu Lisesi, Alanya/Türkiye, [email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7659-8657. -

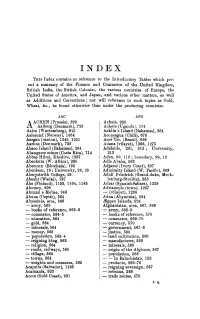

Fables Which L•Re- Ent a Summary of the Finance and Commerce of the Unit

INDEX THIS Index contains no reference to the Introductory 'fables which l•re• ent a summary of the Finance and Commerce of the United Kingdom, British India., the British Colanies, the various countries of Europe, the United States of America, and Japan, and various other matters, as well as Additions and Con-ections ; nor will reference to such topics as Gold, Wheat, &c., be found otherwise than under the producing countries. AAC AFG ACHEN (Prussia), 829 Achaia, 920 A Aalborg (Denmark), 725 Achole (Uganda), 174 Au.len (Wurtemberg}, 915 Acklin's Island (Baha.mas), 264 Aalesund (Norwu.y), 1064 Aconcagua (Chili), 676 Aargu.u (cu.nton), 1249, 1251 Acre Ter. (Brazil), 659 Aarhus (Denmu.rk), 725 Adana (vilayet), 1266, 1275 Abaca Islu.nd (Baham&l!}, 264 Adelaide, 281, 312 ; University, Abu.ngarez mines (Costa Rica), 714 313 Abbas Hilmi, Khedive, 1287 Aden, 99. 119 ; boundary, 99, 12 Abeokuta (W. Africa), 230 Adis Ababa, 563 Abercorn (Rhodesia), 192 Adjame (Ivory Coast), 807 Aberdeen, 19; University, 28, 29 Admiralty Island (W. Pacific), 863 Aberystwith College, 29 Adolf Friedrich (Grand-duke, Meck- Abeshr (Wadai), 797 lenburg-Strelitz), 888 Abo (Finlu.nd), 1163, 1164, 1186 Adrar (Spanish Sahara), 1229 Abomey, 808 Adriu.nople (town), 1267 Abrnzzi e M.olise, 946 - (vilayet), 1266 Abuua. (Coptic), 664 Adua (Abyssinia), 564 Abyssinia, area, 663 lEgean Islands, 924 -army, 663 Afghanistan, area, 567, 568 - books of reference, 666-6 : - army, 568-9 - commerce, 664-6 - books of reference, 570 - education, 664 - commerce, 569-70 -gold, 564 - currency, -

Persistence of Armenian and Greek Influence in Turkey

Minorities and Long-run Development: Persistence of Armenian and Greek Influence in Turkey ∗ Cemal Eren Arbatlı Gunes Gokmen y July 2015 Abstract Mass deportations and killings of Ottoman Armenians during WWI and the Greek-Turkish population exchange after the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922 were the two major events of the early 20th century that permanently changed the ethno-religious landscape of Anatolia. These events marked the end of centuries-long coexistence of the Muslim populations with the two biggest Christian communities of the region. These communities played a dominant role in craftsmanship, manufacturing, commerce and trade in the Empire. In this paper, we empirically investigate the long-run contribution of the Armenian and Greek communities in the Ottoman period on regional development in modern Turkey. We show that districts with greater presence of Greek and Armenian minorities at the end of the 19th century are systematically more densely populated, more urbanized and exhibit greater economic activity today. These results are qualitatively robust to accounting for an extensive set of geographical and historical factors that might have influenced long-run development on the one hand and minority settlement patterns on the other. We explore two potential channels of persistence. First, we provide evidence that Greeks and Armenians might have contributed to long-run economic development through their legacy on human capital accumulation at the local level. This finding possibly reflects the role of inter-group spillovers of cultural values, technology and know-how as well as the self-selection of skilled labor into modern economic sectors established by Armenian and Greek entrepreneurs. -

M. Sabri KOZ Devlet Ve Vilâyet Salnameleri, Il Yilliklari

ADANA VILAYETI SALNAMELERINDE YATIRLAR, ZIYARETLER M. Sabri KOZ Devlet ve Vilâyet Salnameleri, Il Yilliklari: Devlet salnameleri, Tanzimat'tan sonra Batiya açilmanin tanitma ve bilgilendirmeye yönelik yayin çalismalarindandir. Devletin yakandan asagiya kadar yönetim birimlerini, merkezden atanan devlet memurlarim ya da yerel yöneticileri, istatistiksel bilgileri veren bu kitaplarin ilki 1847'de çikmis, 1922'ye kadar 68 yil için yayimlanmistir. Devlet Salnâmeleri'nin yönetim birimleri, yer, kurum ve yönetici, memur adlari disinda yerel konulara fazla yer ayiramadigi biliniyor. Bu yüzden 1866'dan itibaren Bosna Vilâyeti Salnamesi ile baslayip 1921- 1922'de yayimlanan Müstakil Bolu Sancagi Salnamesi ile son bulan vilâyet salnameleri görülen lüzum üzerine yayimlanmaya baslamis, böylece yerel bilgilerin daha ayrintili bir biçimde ele alindigi resmî kaynaklar ortaya çikmistir1. l Osmanli döneminde yayimlanan devlet, vilayet ve diger özel salnamelerle ilgili yararli bir katalog yayimlanmistir: Hasan Duman (Haz.), Osmanli Yilliklari (Salnameler ve Nevsaller), Bibliyografya ve Bazi Istanbul Kütüphanelerine Göre Bir Katalog Denemesi, Islâm Tarih, Sanat ve Kültürü Arastirma Merkezi (1RCICA) Yayinlan; Istanbul, 1982; 135, 7 s. Ancak aradan geçen yillar boyunca elde edilen yeni bilgi, künye ve kütüphaneler eklenerek gelistirilmesi, bulunabilecek eksik ve yanlislarin düzeltilmesi yerinde olacaktir. M. Seyfettin Ozege'nin, Eski Harflerle Basilmis Türkçe Eserler Katalogu adli eserinde de salname künyelerine yer verilmistir. (C.1-5, Istanbul, 1971-1979, -

20 CIÉPO Symposium

University of Crete Foundation for Research Department of History and Technology - Hellas and Archaeology Institute for Mediterranean Studies 20th CIÉPO Symposium New Trends in Ottoman Studies Rethymno, Crete, Greece 27 June – 1 July 2012 Organised in collaboration with the Region of Crete, Regional Unit of Rethymno, and the Municipality of Rethymno 1 Organising Committee Gülsün Aksoy-Aivali Antonis Anastasopoulos Elias Kolovos Marinos Sariyannis Honorary Committee Prof. Jean-Louis Bacqué-Grammont (Honorary President, CIÉPO) Prof. Vassilis Demetriades (Honorary Researcher, IMS/FORTH) Prof. Costas Fotakis (President, FORTH) Prof. Christos Hadziiossif (Director, IMS/FORTH) Prof. Katerina Kopaka (Dean, School of Letters, University of Crete) Ms Maria Lioni (Regional Vice Governor of Crete, Rethymno) Mr Giorgis Marinakis (Mayor of Rethymno) Ass. Prof. Socrates Petmezas (Chair, Department of History and Archaeology, University of Crete) Prof. Euripides G. Stephanou (Rector, University of Crete) Prof. Michael Ursinus (President, CIÉPO) Prof. Elizabeth A. Zachariadou (Honorary Researcher, IMS/FORTH) Symposium Secretariat Eleni Sfakianaki Katerina Stathi Technical Support Alexandros Maridakis Symposium Assistants Marilena Bali Angeliki Garidi Michalis Georgellis Despoina Giannakaki Myrsini Kavalari Georgia Korontzi Alexandra Kriti Christos Kyriakopoulos Giannis Lambrakis Iordanis Panagiotidis Stelios Parlamas Stamatia Partsafa Ioanna Petroulidi Milan Prodanović Panagiota Sfyridaki 2 Panel Abstracts 1. Panels are listed in alphabetical order on the basis of the family name of the panel leader. 2. The names of the other panelists of each panel are listed by order of presentation. 3. The panels’ paper abstracts are listed together with the abstracts of the independent papers in the next section. 3 A. Nükhet Adıyeke (başkan), Nuri Adıyeke, Mehmet Ali Demirbaş, Melike Kara (Wed 27, 16.30, r. -

The Ottoman Empire

TEACHING MODERN SOUTHEAST EUROPEAN HISTORY Alternative Educational Materials The Ottoman Empire THE PUBLICATIONS AND TEACHER TRAINING ACTIVITIES OF THE JOINT HISTORY PROJECT HAVE BEEN MADE POSSIBLE THROUGH THE KIND FINANCIAL BACKING OF THE FOLLOWING: UK FOREIGN & COMMONWEALTH OFFICE Norwegian People’s Aid United States Institute of Peace Swiss Development Agency DR. PETER MAHRINGER FONDS TWO ANONYMOUS DONORS THE CYPRUS FEDERATION OF AMERICA Royal Dutch Embassy in Athens WINSTON FOUNDATION FOR WORLD PEACE And with particular thanks for the continued support of: 2nd Edition in the English Language CDRSEE Rapporteur to the Board for the Joint History Project: Costa Carras Executive Director: Nenad Sebek Director of Programmes: Corinna Noack-Aetopulos CDRSEE Project Team: George Georgoudis, Biljana Meshkovska, Antonis Hadjiyannakis, Jennifer Antoniadis and Louise Kallora-Stimpson English Language Proofreader: Jenny Demetriou Graphic Designer: Anagramma Graphic Designs, Kallidromiou str., 10683, Athens, Greece Printing House: Petros Ballidis and Co., Ermou 4, Metamorfosi 14452, Athens, Greece Disclaimer: The designations employed and presentation of the material in the book do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the publisher (CDRSEE) nor on the sponsors. This book contains the views expressed by the authors in their individual capacity and may not necessarily reflect the views of the CDRSEE and the sponsoring agencies. Print run: 1000 Copyright: Center for Democracy and Reconciliation in Southeast Europe (CDRSEE) -

Re-Envisioning Global Development

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:46 24 May 2016 Re-Envisioning Global Development Re-Envisioning Global Development elaborates an alternative ontology and way of thinking about global development during recent centuries – one linked, not to nations and regions, but to a set of essentially trans- national relations and connections. This angle of vision provides the basis for an original perspective on capitalist development from its origins to the present day. Most approaches to understanding contemporary development assume that industrial capitalism was achieved through a process of nationally organised economic growth, and that in recent years its organisation has become increasingly trans-local or global. However, Halperin shows that nationally organised economic growth has rarely been the case – it has only recently come to characterise a few countries and for only a few decades. Halperin argues that capitalist development has, everywhere and from the start, involved – not whole nations or societies – but only sectors or geographical areas within states. By bringing this aspect of historically ‘normal’ capitalist development into clearer focus, the book clarifies the spe- cific conditions and circumstances that enabled European economies to pur- sue a more broad-based development following World War II, and what pre- vented a similar outcome in the contemporary ‘third world’. It also clarifies the nature, spatial extent and circumstances of current globalising trends. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:46 24 May 2016 Wide-ranging and provocative, this innovative text is required reading for advanced level students and scholars in development studies, develop- ment economics and political science. Sandra Halperin is Professor of International Relations and Co-Director of the Centre for Global and Transnational Politics at Royal Holloway, Uni- versity of London. -

Cihannüma TARİH VE COĞRAFYA ARAŞTIRMALARI DERGİSİ JOURNAL of HISTORY and GEOGRAPHY STUDIES

Cihannüma TARİH VE COĞRAFYA ARAŞTIRMALARI DERGİSİ JOURNAL OF HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY STUDIES CİLT / VOLUME III SAYI / ISSUE 1 Temmuz / July 2017 İZMİR KÂTİP ÇELEBİ ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL VE BEŞERİ BİLİMLER FAKÜLTESİ Cihannüma TARİH VE COĞRAFYA ARAŞTIRMALARI DERGİSİ JOURNAL OF HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY STUDIES P-ISSN: 2149-0678 / E-ISSN: 2148-8843 Sahibi/Owner İzmir Kâtip Çelebi Üniversitesi Sosyal ve Beşeri Bilimler Fakültesi adına Prof. Dr. Turan GÖKÇE Editör / Editor Doç. Dr. Cahit TELCİ, İzmir Kâtip Çelebi Üniversitesi, Türkiye Sorumlu Yazı İşleri Müdürü / Responsible Editor Yrd. Doç. Dr. Beycan HOCAOĞLU, İzmir Kâtip Çelebi Üniversitesi, Türkiye Yayın Kurulu / Editorial Board Assoc. Prof. Nabil Al-TIKRITI, University of Mary Washington, ABD Doç. Dr. Yahya ARAZ, Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi, Türkiye Dr. Elisabetta BENIGNI, Universitá degli Studi di Torino, İtalya Dr. Zaur GASIMOV, Orient Institut Istanbul, Almanya Prof. Dr. Vehbi GÜNAY, Ege Üniversitesi, Türkiye Assoc. Prof. Barbara S. KINSEY, Universty of Central Florida, ABD Yrd. Doç. Dr. İrfan KOKDAŞ, İzmir Kâtip Çelebi Üniversitesi, Türkiye Doç. Dr. Özer KÜPELİ, İzmir Kâtip Çelebi Üniversitesi, Türkiye Assoc. Prof. Kent F. SCHULL, Binghamton University, ABD Yrd. Doç. Dr. Haydar YALÇIN, İzmir Kâtip Çelebi Üniversitesi, Türkiye Yayın Türü / Publication Type Uluslararası Hakemli Süreli Yayın / International Peer-reviewed Periodicals Yayın Sıklığı / Publication Frequency Yılda İki Sayı / Biannually Yazışma Adresi / CorrespondingAddress İzmir Kâtip Çelebi Üniversitesi Sosyal ve Beşeri Bilimler Fakültesi,