Volume 8, No. 2 Issue 22

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abstract Why We Turn the Page: a Literary Theory Of

ABSTRACT WHY WE TURN THE PAGE: A LITERARY THEORY OF DYNAMIC STRUCTURALISM Justin J. J. Ness, Ph.D. Department of English Northern Illinois University, 2019 David J. Gorman, Director This study claims that every narrative text intrinsically possesses a structure of fixed relationships among its interest components. The progress of literary structuralism gave more attention to the static nature of what a narrative is than it did to the dynamic nature of how it operates. This study seeks to build on the work of those few theorists who have addressed this general oversight and to contribute a more comprehensive framework through which literary critics may better chart the distinct tensions that a narrative text cultivates as it proactively produces interest to motivate a reader’s continued investment therein. This study asserts that the interest in narrative is premised on three affects— avidity, anxiety, and curiosity—and that tensions within the text are developed through five components of discourse: event, description, dialog, sequence, and presentation. NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DEKALB, ILLINOIS MAY 2019 WHY WE TURN THE PAGE: A LITERARY THEORY OF DYNAMIC STRUCTURALISM BY JUSTIN J. J. NESS ©2019 Justin J. J. Ness A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Dissertation Director: David J. Gorman ACKNOWLEDGMENTS David Gorman, the director of my project, introduced me to literary structuralism six years ago and has ever since challenged me to ask the simple questions that most people take for granted, to “dare to be stupid.” This honesty about my own ignorance was—in one sense, perhaps the most important sense—the beginning of my life as a scholar. -

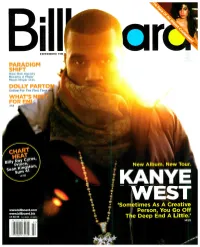

`Sometimes As a Creative

EXPERIENCE THE PARADIGM SHIFT How One Agency Became A Major Music Player >P.25 DOLLY PARTO Online For The First Tim WHAT'S FOR >P.8 New Album. New Tour. KANYE WEST `Sometimes As A Creative www.billboard.com Person, You Go Off www.billboard.biz US $6.99 CAN $8.99 UK E5.50 The Deep End A Little.' >P.22 THE YEAR MARK ROHBON VERSION THE CRITICS AIE IAVIN! "HAVING PRODUCED AMY WINEHOUSE AND LILY ALLEN, MARK RONSON IS ON A REAL ROLL IN 2007. FEATURING GUEST VOCALISTS LIKE ALLEN, IN NOUS AND ROBBIE WILLIAMS, THE WHOLE THING PLAYS LIKE THE ULTIMATE HIPSTER PARTY MIXTAPE. BEST OF ALL? `STOP ME,' THE MOST SOULFUL RAVE SINCE GNARLS BARKLEY'S `CRAZY." PEOPLE MAGAZINE "RONSON JOYOUSLY TWISTS POPULAR TUNES BY EVERYONE FROM RA TO COLDPLAY TO BRITNEY SPEARS, AND - WHAT DO YOU KNOW! - IT TURNS OUT TO BE THE MONSTER JAM OF THE SEASON! REGARDLESS OF WHO'S OH THE MIC, VERSION SUCCEEDS. GRADE A" ENT 431,11:1;14I WEEKLY "THE EMERGING RONSON SOUND IS MOTOWN MEETS HIP -HOP MEETS RETRO BRIT -POP. IN BRITAIN, `STOP ME,' THE COVER OF THE SMITHS' `STOP ME IF YOU THINK YOU'VE HEARD THIS ONE BEFORE,' IS # 1 AND THE ALBUM SOARED TO #2! COULD THIS ROCK STAR DJ ACTUALLY BECOME A ROCK STAR ?" NEW YORK TIMES "RONSON UNITES TWO ANTITHETICAL WORLDS - RECENT AND CLASSIC BRITPOP WITH VINTAGE AMERICAN R &B. LILY ALLEN, AMY WINEHOUSE, ROBBIE WILLIAMS COVER KAISER CHIEFS, COLDPLAY, AND THE SMITHS OVER BLARING HORNS, AND ORGANIC BEATS. SHARP ARRANGING SKILLS AND SUITABLY ANGULAR PERFORMANCES! * * * *" SPIN THE SOUNDTRACK TO YOUR SUMMER! THE . -

Commentary V2 Proofed FINAL

!1 Sonic autoethnographies: six | records | of | the | listening | self Iain Findlay-Walsh Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Music (Composition) School of Culture and Creative Arts College of Arts University of Glasgow February 2016 !2 Portfolio contents 1. Commentary (including portfolio on USB flash drive) 2. plastic 2 x CD case - corresponding to postface 3. 1 x CD wrapped in packing tape - corresponding to In Posterface: 1 4. 12” art print in PVC sleeve - corresponding to Somehere in 5. removable vinyl sticker - corresponding to _omiting in the changing room !3 Acknowledgements Thanks to Louisa-Jane, Blue and Bon Findlay-Walsh for providing the support and space to develop and complete this work. Thanks to Nick Fells and Martin Parker Dixon, who supervised throughout the project. Thanks to the following for supporting me in this work, providing opportunities to test and present parts of it, and contributing to the ideas and practice. Alasdair Campbell, Clare McFarlane, Tristan Partridge, John Campbell, May Campbell, Ruth Campbell, FK Alexander, Rob Alexander, Nick Anderson, Calum Beith, Rosana Cade, Liam Casey, Martin Cloonan, Lewis Cook, Carlo Cubero, Euan Currie, Anne Danielsen, Neil Davidson, Barry Esson, Stuart Evans, Paul Gallagher, Mark Grimshaw, Louise Harris, Paul Henry, Fielding Hope, Katia Isakoff, Bryony McIntyre, Emily McLaren, Jamie McNeill, Rickie McNeill, Felipe Otondo, Dale Perkins, Emily Roff, Calum Scott, Toby Seay, Sam Smith, Craig Tannoch, Rupert Till, Fritz Welch, Simon Zagorski-Thomas. !4 Abstract This commentary accompanies a portfolio of pieces which combine soundscape composition and record production methods with aspects of autoethnographic practice. This work constitutes embodied research into relations between everyday auditory experience, music production and reception, and selfhood. -

Triller Network Acquires Verzuz: Exclusive

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayMARCH 9, 2021 Page 1 of 25 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Triller Network Acquires Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debuts at No. 1 on Billboard’s lion audience impressions, up 16%). Top Country• Verzuz Albums Founders chart dated April 18. In its first week (endingVerzuz: April 9), it Exclusive earnedSwizz 46,000 Beatz equivalent & album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cordingTimbaland to Nielsen Talk Music/MRC Data. andBY total GAIL Country MITCHELL Airplay No. 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideTriller Partnership: marks Hunt’s second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chart‘This and fourthPuts a top Light 10. It followsVerzuz, freshman the LPpopular livestream music platform creat- in music todayYoung’s than Verzuz,” first of six said chart Bobby entries, Sarnevesht “Sleep With,- MontevalloBack on, which Creatives’ arrived at theed summit by Swizz in No Beatz- and Timbaland, has been acquired executive chairmanout You,” andreached co-owner No. 2 in of December Triller, in 2016. an- He vember 2014 and reigned for nineby weeks. Triller To Network, date, parent company of the Triller app. -

HECUBA by Euripides

HECUBA by Euripides translated by Jay Kardan and Laura-Gray Street POLYDORUS HECUBA CHORUS POLYXENA ODYSSEUS TALTHYBIUS THERAPAINA AGAMEMNON POLYMESTOR Script copyright Jay Kardan and Laura-Gray Street. Apply to the authors for performance permissions. Hecuba — translated by Kardan and Street — in Didaskalia 8 (2011) 32 POLYDORUS I come from bleakest darkness, where corpses lurk and Hades lives apart from other gods. I am Polydorus, youngest son of Hecuba and Priam. My father, worried Troy might fall to Greek offensives, sent me here, to Thrace, my mother’s father’s home and land of his friend Polymestor, who controls this rich plain of the Chersonese and its people with his spear. My father sent a large stash of gold with me, to insure that, if Ilium’s walls indeed (10) were toppled, I’d be provided for. He did all this because I was too young to wear armor, my arms too gangly to carry a lance. As long as the towers of Troy remained intact, and the stones that marked our boundaries stood upright, and my brother Hector was lucky with his spear, I thrived living here with my father’s Thracian friend, like some hapless sapling. (20) But once Troy was shattered—Hector dead, our home eviscerated, and my father himself slaughtered on Apollo’s altar by Achilles’ murderous son— then Polymester killed me. This “friend” tossed me dead into the ocean for the sake of gold, so he could keep Priam’s wealth for himself. My lifeless body washes ashore and washes back to sea with the waves’ endless ebb and flow, and remains unmourned, unburied. -

The Comic Way Towards the Universal Self: Socioecological Trauma and the Wounds Left by Survival

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2021 The Comic Way Towards the Universal Self: Socioecological Trauma and the Wounds Left by Survival Gabriel Bugarin Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bugarin, Gabriel, "The Comic Way Towards the Universal Self: Socioecological Trauma and the Wounds Left by Survival" (2021). WWU Graduate School Collection. 1034. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/1034 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Comic Way Towards the Universal Self: Socioecological Trauma and the Wounds Left by Survival By Gabriel Bugarin Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts ADVISORY COMMITTEE Dr. Kathryn Trueblood, Chair Dr. Jane Wong Dr. Chris Loar GRADUATE SCHOOL David L. Patrick, Dean Master’s Thesis In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non-exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. -

Sojourner Adjustment : a Diary Study

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1992 Sojourner Adjustment : A Diary Study Susan Elizabeth Hemstreet Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hemstreet, Susan Elizabeth, "Sojourner Adjustment : A Diary Study" (1992). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4377. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6261 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Susan Elizabeth Hemstreet for the Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages presented January 21, 1992. Title: Sojourner Adjustment: A Diary Study. APPROVED BY THE MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Maqone ~. Terdal, Chair Suwako Watanabe The focus of the ethnographic diary study is introduced and contextualized in the opening chapter with a site description. The thesis examines the diaries written during a sojourn of over two years in Japan . and proposes to answer the question, "How did the sojourner's initial maladjustment subsequently develop into satisfactory adjustment?" 2 The literature on diary studies, culture shock and sojourner adjustment is reviewed in order to establish standards of the diary study genre and a framework from which to analyze the diary. Using the qualitative methods of a diary study, salient themes of the adjustment are examined. The diarist's progression through the adjustment stages as proposed by the literature is supported, and the coping strategies of escapism, reaching out to people, writing, positive thinking, religious beliefs, compulsive behaviors, goal-setting and seeing the experience as finite are discussed in depth. -

EU Page 01 COVER.Indd

entertaining u newspaper JACKSONVILLE design issue Daryl Bunn exhibit at Jane Gray Gallery | 48 Hour Film Project | Suicide Notes: new record store | Matthew’s Fine Dining free weekly guide to entertainment and more | august 9-15, 2007 | www.eujacksonville.com 2 august 9-15, 2007 | entertaining u newspaper table of contents Cover Photo by Rachel Best Henley - Home of Daryl Bunn feature Design Nation ................................................................................................. PAGES 16-23 Daryl Bunn (interview) ............................................................................. PAGES 16-17 Urban Architectural Design ...............................................................................PAGE 18 Personal Design ....................................................................................... PAGES 18-21 Interior Design .................................................................................................PAGE 19 Landscape Design ...........................................................................................PAGE 20 Tattoo Design ...................................................................................................PAGE 21 Event Design ............................................................................................ PAGES 22-23 Music Design .................................................................................................PAGES 23 movies Movies in Theaters this Week ........................................................................... -

Metonymy & Trauma

ii METONYMY & TRAUMA RE-PRESENTING DEATH IN THE LITERATURE OF W. G. S E B A L D Andrew Michael Watts A research dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD English University of New South Wales 2006 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: WATTS First name: ANDREW Other names: MICHAEL Abbreviation for degree as given in the University Calendar: PhD School: ENGLISH Faculty: ARTS Title: Metonymy & Trauma: Re-presenting Death in the Literature of W. G. Sebald Abstract 350 words maximim: (PLEASE TYPE) Novel: Fragments of a Former Moon The novel Fragments of a Former Moon (FFM) invokes the paradoxical earlier death of the still-living protagonist. The unmarried German woman is told that her skeletal remains have been discovered in Israel, thirty-eight years since her body was interred in 1967. This absurd premise raises issues of representing death in contemporary culture; death's destabilising effect on the individual's textual representation; post-Enlightenmentdissolution of the modern rational self; and problems of mimetic post- Holocaust representation. Using W G Sebald's fiction as a point of departure, FFM's photographic illustrations connote modes of textual representation that disrupt the autobiographical self, invoking mortality and its a-temporal (representational) displacement. As with Sebald's recurring references to the Holocaust, FFM depicts a psychologically unstable protagonist seeking to recover repressed memories of an absent past. Research dissertation: Metonymy &Trauma: Re-presenting Death in the Literature of W. G. Sebald The dissertation centres on the effect of metonymy in the rhetoric of textually-constructedidentity and its contemporary representation in the face of death. -

Teen Tour of the Summer: Star-Studded Nextfest to Visit 29 Cities Across North America

May 23, 2007 Teen Tour of the Summer: Star-Studded Nextfest to Visit 29 Cities Across North America Aly & AJ, Corbin Bleu and Drake Bell to Headline Nextfest With Special Guest Bianca Ryan Tickets on Sale Beginning June 2nd LOS ANGELES, May 23 /PRNewswire-FirstCall/ -- Bringing a blast of youthful energy to this summer's tour schedule, Live Nation (NYSE: LYV) today announced dates for Nextfest, the hottest teen tour in recent memory. Headlined by superstars Aly & AJ, Corbin Bleu and Drake Bell, and joined by newcomer Bianca Ryan, Nextfest kicks off on July 11th at Phoenix, Arizona's Dodge Theatre and runs through September 1st, hitting 29 cities in all. Tickets for the Live Nation produced tour go on sale nationwide beginning on Saturday, June 2nd and are available at www.livenation.com. A full list of dates is below. Aly & AJ are readying their third Hollywood Records album, Insomniatic, for a July 10th release. With anticipation building fueled by the hit single "Potential Break Up Song," Aly & AJ are poised to improve upon the platinum plus status of their previous album Into The Rush. The duo is already busy promoting the new album and single, as well as their upcoming MTV film, Super Sweet 16, due out July 8th, with multiple appearances scheduled on MTV and other national television shows. They also grace millions of Post's Honeycomb cereal boxes in a national promotion. Aly & AJ are currently filming the pilot to their own MTV show, some of which will take place on this tour. Coming soon: The launch of an "Aly & AJ" book series, "Aly & AJ" Xbox and Nintendo video games, a doll series by Huckleberry Toys, apparel by FEA Merchandising, backpacks and accessories by Accessory Network, headwear by Bioworld, jewelry and hair accessories by IMT, cosmetics by Townley Girl and domestics by J Franco. -

FTI 2009 CD DVD Consumer Price List

CHILDREN'S CD and DVD ENTERTAINMENT [email protected] Canadian wholesale price list January 2009 www.firetheimagination.ca code description retail AL SIMMONS MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 801464200629 AL SIMMONS: CELERY STALKS AT MIDNIGHT - CD $10.95 801464200520 AL SIMMONS: SOMETHING FISHY - CD $10.95 ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS (DVDs also available) MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 793018298629 ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS SOUNDTRACK (2007) - CD $26.95 076744008824 CHIPMUNKS ADVENTURE - CD $15.95 5099921310225 CHIPMUNKS SING THE BEATLES - CD $12.95 ALY AND AJ MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 720616264220 ALY AND AJ: INSOMNIATIC - CD $22.95 720616264022 ALY AND AJ: INTO THE RUSH (Deluxe Edition) - CD with DVD $23.95 720616250520 ALY AND AJ: INTO THE RUSH - CD $22.95 ANNE MURRAY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 724353548520 ANNE MURRAY: THERE'S A HIPPO IN MY TUB - CD $16.95 ANN RACHLIN - GREAT COMPOSERS SPOKEN WORD 9781902680088 ANN RACHLIN: HAPPY BIRTHDAY, MR. BEETHOVEN: THE LIFE OF BEETHOVEN - CD $19.95 9781902680095 ANN RACHLIN: MOZART THE MIRACLE MAESTRO: THE LIFE OF MOZART - CD $19.95 9781902680125 ANN RACHLIN: MR. HANDEL'S FIREWORKS PARTY: THE LIFE OF HANDEL - CD $19.95 9781902680101 ANN RACHLIN: ONCE UPON THE THAMES: THE LIFE OF HANDEL - CD $19.95 9781902680118 ANN RACHLIN: PAPA HAYDN'S SURPRISE: THE LIFE OF HAYDN - CD $19.95 ANN RACHLIN - RUSSIAN BALLETS SPOKEN WORD 9781902680163 ANN RACHLIN: CINDERELLA: THE STORY OF THE BALLET - CD $19.95 9781902680187 ANN RACHLIN: FIREBIRD, THE: THE STORY OF THE BALLET - CD $19.95 9781902680149 ANN RACHLIN: NUTCRACKER: THE STORY OF THE -

Music.Video.Print.Kids Cover Final2 6/27/07 9:14 PM Page 2

Cover_final3 6/28/07 7:51 PM Page 1 September 2007 New Releases September 25, 2007 October 2, 2007 music.video.print.kids Cover_final2 6/27/07 9:14 PM Page 2 Deck the halls this season with the highly sought after and never released to retail Relient K Christmas album. It’s finally available on com- pact disc with 3 new songs this Christmas. Cover_final3 6/28/07 7:47 PM Page 3 David Crowder Band REMEDY is coming 9.25.07! Cover_final2 6/27/07 9:14 PM Page 4 Bebo Norman’s very first Christmas album. CHRISTMAS... FROM THE REALMS OF GLORY brings Christmas to stores nationwide 10.2.07! Cover_final2 6/27/07 9:14 PM Page 5 Amy Grant Greatest Hits All new, first ever COMPLETE COLLECTION of Amy’s hits spanning her entire 30 year career in music available 10.2.07 Sept07_Contents_prf1 6/27/07 9:19 PM Page 2 .september 2007 5 Check Your Stock 6 Product Updates 7 Street Date 09.25.07 27 Street Date 10.02.07 39 Street Date 10.09.07 41 Order Today 43 On Tour 49 New Release Order Form September 25, 2007 RECORDED MUSIC PRINT ALY & AJ Acoustic Hearts of Winter (p. 14) BOHANNON, MITCH Cut Capo Guitar Course (p. 24) BRENNAN, MOYA Signature (p. 14) DAVID CROWDER*BAND Remedy (p. 24) CASH, JOHNNY Gospel Music of Johnny Cash (p. 9) VARIOUS Christmas Carols (p. 25) DAVID CROWDER*BAND Remedy (p. 8) VARIOUS Christmas Medleys (p. 25) GREENE, JESSICA 4 The World (p. 16) HOBBS, DARWIN The Best Of Darwin Hobbs (p.