Sojourner Adjustment : a Diary Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hello, Ladies and Gentlemen. It's Great to Be Here in Cleveland, Ohio, Or In

Hello, ladies and gentlemen. It's great to be here in Cleveland, Ohio, or in Ohio. And today I'm going to share a message of resilience and redemption, a message of hope, a message that will hopefully rejuvenate you. How many of you parked out? No, no red need your hands. But a lot of you that I seek a lot for child welfare as Foster Paris and Department of Social Services and such as a lot of people that I meet at this time of the year is burnt out time, and it's all right. That tells me it's all right to be burnt out. That tells me you are on fire at one point. So I'm about to get to fire back. And also a lot of you that became false apparent with social workers that I found. Don't try to get rich. It's not something you chose like a get rich doing this. I've met the most special people that are fought er person social workers, and I realized they're not doing it for the outcome. They're doing it for the outcome. And I'm here to share with you the outcome of what is possible from a great social worker and great, loving, committed foster parents that were so dedicated to me growing up to becoming the man I am. See how I came in the story, how I came in this life is a crazy story my mother won't tell to my face. They to me, to my face all the issues that happened. -

Sense of Place in Appalachia. INSTITUTION East Tennessee State Univ., Johnson City

DOCUMENT. RESUME ED 313 194 RC 017 330 AUTHOR Arnow, Pat, Ed. TITLE Sense of Place in Appalachia. INSTITUTION East Tennessee State Univ., Johnson City. Center for Appalachian Sttdies and Services. PUB DATE 89 NOTE 49p.; Photographs will not reproduce well. AVAILABLE FROMNow and Then, CASS, Box 19180A, ETSU, Johnson City, TN 37614-0002 ($3.50 each; subscription $9.00 individual and $12.00 institution). PUB TYPE Collected Works -Serials (022) -- Viewpoints (120) -- Creative Works (Literature,Drama,Fine Arts) (030) JOURNAL CIT Now and Then; v6 n2 Sum 1989 EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Essays; Interviews; *Novels; Photographs; Poetry; *Regional Attitudes; Regional Characteristics; *Rural Areas; Short Stories IDENTIFIERS *Appalachia; Appalachian Literature; Appalachian People; *Place Identity; Regionalism; Rural Culture ABSTRACT This journal issue contains interviews, essays, short stc-ies, and poetry focusing on sense of place in Appalachia. In iLterviews, author Wilma Dykeman discussed past and recent novels set in Appalachia with interviewer Sandra L. Ballard; and novelist Lee Smith spoke with interviewer Pat Arnow about how Appalachia has shaped her writing. Essays include "Eminent Domain" by Amy Tipton Gray, "You Can't Go Home If You Haven't Been Away" by Pauline Binkley Cheek, and "Here and Elsewhere" by Fred Waage (views of regionalism from writers Gurney Norman, Lou Crabtree, Joe Bruchac, Linda Hogan, Penelope Schott and Hugh Nissenson). Short stories include "Letcher" by Sondra Millner, "Baptismal" by Randy Oakes, and "A Country Summer" by Lance Olsen. Poems include "Honey, You Drive" by Jo Carson, "The Widow Riley Tells It Like It Is" by P. J. Laska, "Words on Stone" by Wayne-Hogan, "Reeling In" by Jim Clark, "Traveler's Rest" by Walter Haden, "Houses" by Georgeann Eskievich Rettberg, "Seasonal Pig" by J. -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

Parents of New Rising 6Th Graders, Welcome to Providence Day. This Is

Parents of New Rising 6th Graders, Welcome to Providence Day. This is an exciting time for both you and your child, and yet, we realize there is a great deal of information to sort through. This letter will explain the summer reading expectation for your child’s English class. In English, we will spend a good part of the year reading novels to help explore literary elements, practice sound reading skills, and promote clear communication. In the summer, we want your son or daughter to stay attached to reading and novels. This year, with the help of Mrs. Bynum (Head of the MS English Dept), Mrs. May (Middle School Librarian) and the MS Battle of the Books Club, we have compiled a list of what we believe to be a great variety of interesting novels from which your child will select at least one novel to read independently. When classes resume in August, each student will be asked to complete activities in English class related to the novel of their choosing. In addition, we also request that our students not read any of the novels attached to our English curriculum for the coming year. We would like to make sure you can follow along with very specific reading assignments and skills as we work our way through these pieces. It is preferred that we read along with classmates and make discoveries and predictions together. If you have any questions, please reach out to either of us. Have a wonderful summer. We look forward to seeing you in August. Enjoy the reading! Sincerely, Connie Scully [email protected] Ryan Harper [email protected] 20162017 Rising 6th Grade Summer Reading Choices Directions: Select one novel from this list to read this summer. -

Part Four Jack the Call

"I told him I wouldn't tell you," I explained. "It's so weird," he said. "I have no idea why he's mad at me all of a sudden. None. Can't you at least give me a hint?" I looked over at where August was across the room, talking to our moms. I wasn't about to break my solid oath that I wouldn't tell anyone about what he overheard at Halloween, but I felt bad for Jack. "Bleeding Scream," I whispered in his ear, and then walked away. Part Four Jack Now here is my secret. It is very simple. It is only with one's heart that one can see clearly. What is essential is invisible to the eye. —Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince The Call So in August my parents got this call from Mr. Tushman, the middle-school director. And my Mom said: "Maybe he calls all the new students to welcome them," and my dad said: "That's a lot of kids he'd be calling." So my mom called him back, and I could hear her talking to Mr. Tushman on the phone. This is exactly what she said: "Oh, hi, Mr. Tushman. This is Amanda Will, returning your call? Pause. Oh, thank you! That's so nice of you to say. He is looking forward to it. Pause. Yes. Pause. Yeah. Pause. Oh. Sure. Long pause. Ohhh. Uh-huh. Pause. Well, that's so nice of you to say. Pause. Sure. Ohh. Wow. Ohhhh. Super long pause. I see, of course. -

CA M P W O O D. Jan, 4Th, 1862. Dear Sister:- I Received Your Letter

51 CA M P W O O D. Jan, 4th, 1862. Dear Sister:- I received your letter yesterday and was delighted to learn when I read it that you are all well at home. It shocked me some to hear of Dr. Clover’s death. This makes two very unexpected deaths in Alliance since I left. You spoke of several that were to our school day before your spelling school and I know them all except the last gentleman mentioned. You must describe him more in your nest. I am glad you had such a good spelling school. You spoke about Thomas seeing Mr. Valley. I suppose it is Joseph Rockhill’s brother-in-law. I have not seen anything of John yet. If he is in a battery it is likely I will see him, but if you hear what battery he is in, please inform me. Every letter I get they commenced by saying that you do not know of anything to write but I believe I have not seen a sheet come to camp yet that was not filled on every side and generally some written cross ways. That is just the way I think when I commence to write, but before I am done the sheet is full on every side. P.D.Green, the man Father saw at Urbana, from our battery, got back last evening. He brought between fifty and seventy five letters for the batter and a package of Mittens from the good folks at Randolph for our squad. There were more than a pair a piece for us; I think there were about thirty pair. -

AC/DC BONFIRE 01 Jailbreak 02 It's a Long Way to the Top 03 She's Got

AC/DC AEROSMITH BONFIRE PANDORA’S BOX DISC II 01 Toys in the Attic 01 Jailbreak 02 Round and Round 02 It’s a Long Way to the Top 03 Krawhitham 03 She’s Got the Jack 04 You See Me Crying 04 Live Wire 05 Sweet Emotion 05 T.N.T. 06 No More No More 07 Walk This Way 06 Let There Be Rock 08 I Wanna Know Why 07 Problem Child 09 Big 10” Record 08 Rocker 10 Rats in the Cellar 09 Whole Lotta Rosie 11 Last Child 10 What’s Next to the Moon? 12 All Your Love 13 Soul Saver 11 Highway to Hell 14 Nobody’s Fault 12 Girls Got Rhythm 15 Lick and a Promise 13 Walk All Over You 16 Adam’s Apple 14 Shot Down in Flames 17 Draw the Line 15 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 18 Critical Mass 16 Ride On AEROSMITH PANDORA’S BOX DISC III AC/DC 01 Kings and Queens BACK IN BLACK 02 Milk Cow Blues 01 Hells Bells 03 I Live in Connecticut 02 Shoot to Thrill 04 Three Mile Smile 05 Let It Slide 03 What Do You Do For Money Honey? 06 Cheesecake 04 Given the Dog a Bone 07 Bone to Bone (Coney Island White Fish) 05 Let Me Put My Love Into You 08 No Surprize 06 Back in Black 09 Come Together 07 You Shook Me All Night Long 10 Downtown Charlie 11 Sharpshooter 08 Have a Drink On Me 12 Shithouse Shuffle 09 Shake a Leg 13 South Station Blues 10 Rock and Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution 14 Riff and Roll 15 Jailbait AEROSMITH 16 Major Barbara 17 Chip Away the Stone PANDORA’S BOX DISC I 18 Helter Skelter 01 When I Needed You 19 Back in the Saddle 02 Make It 03 Movin’ Out AEROSMITH 04 One Way Street PANDORA’S BOX BONUS CD 05 On the Road Again 01 Woman of the World 06 Mama Kin 02 Lord of the Thighs 07 Same Old Song and Dance 03 Sick As a Dog 08 Train ‘Kept a Rollin’ 04 Big Ten Inch 09 Seasons of Wither 05 Kings and Queens 10 Write Me a Letter 06 Remember (Walking in the Sand) 11 Dream On 07 Lightning Strikes 12 Pandora’s Box 08 Let the Music Do the Talking 13 Rattlesnake Shake 09 My Face Your Face 14 Walkin’ the Dog 10 Sheila 15 Lord of the Thighs 11 St. -

Thandie Newton the Enneagram Oliver James Nathaniel Parker

Nathaniel Parker The Inspector’s mystery solved Thandie Newton Embracing otherness The Enneagram explained by Tim Laurence Oliver James Love Bombing 2013 elcome to the second edition of the Hoffman magazine, Wnow celebrating over 45 years of the Hoffman Process around the world. Contents This issue contains a sumptuous smorgasbord of articles to help satisfy the The Story of Hoffman 2 appetite of your mind, body, and spirit. How I Learnt to be Me 4 I am grateful to all our contributors for their willingness to share their Nathaniel Parker 7 stories and experiences with us. I am also delighted that actor Nathaniel Help... I Sound Like 10 Parker agreed to be our front cover star and to share his story with you all. my Mother Our offerings this year include an introduction to the Enneagram with Tim Here to Learn About 13 Laurence, articles on yoga, parenting, mindfulness, addictions, and nutrition, Love as well as the chance to win a glorious hamper courtesy of Rude Health. Dunford House Thandie Newton 15 Embracing Otherness Historical, idyllic retreat at the foot of the South Downs This year also sees the launch of an intriguing menu of workshops for you to explore. Our parenting workshops, teenage workshops, one-day What’s Your Number? 18 relationship workshops for couples and individuals, and our Hoffman The Enneagram Explained introductory day, all offer you fresh ways to learn to be more present and The Power of Love 21 loving to those around you. Dunford House is a beautiful and discreet venue set in 60 acres of private Gymnastics for the Soul 24 woodland in West Sussex at the foot of the stunning South Downs, only one Whether this is your first contact with Hoffman, or you are coming back Living a Souful Life 28 for second helpings, I hope you find something here to stimulate your hour from London. -

Narrative Structure and Reimagined Negotiations in the Victorian Female Bildungsroman Devon Boyers

William & Mary W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2019 'I walk pure before God!': Narrative Structure and Reimagined Negotiations in the Victorian Female Bildungsroman Devon Boyers Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Boyers, Devon, "'I walk pure before God!': Narrative Structure and Reimagined Negotiations in the Victorian Female Bildungsroman" (2019). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1366. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1366 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Introduction 3 Independence and Regeneration in Jane Eyre 9 Personal and Public Re-Imaging in North and South 32 Interwoven Bildungsromane in The Small House at Allington 55 Conclusion 68 Boyers 2 Introduction ‘By the time he has decided, after painful soul-searching, the sort of accommodation to the modern world he can honestly make, he has left his adolescence behind and entered upon his maturity.’ – JEROME BUCKLEY, Season of Youth1 The German term Bildungsroman refers to a “novel of formation,” and although German literary critics have debated its meaning, in Anglo-American criticism -

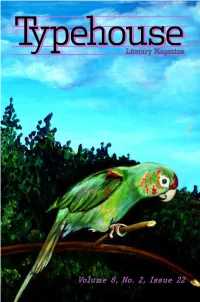

Volume 8, No. 2 Issue 22

Volume 8, No. 2 Issue 22 ©2021 Typehouse Literary Magazine. All rights reserved. No part of this periodical may be reproduced in any form without written permission. Typehouse Literary Magazine is published triannually. Established 2013. Typehouse Literary Magazine Editor in Chief: Val Gryphin Senior Editors: Nadia Benjelloun (Prose) Lily Blackburn (Craft Essay) Jiwon Choi (Poetry) Mariya Khan (Prose and Poetry) Yukyan Lam (Prose) Jared Linder (Prose) Kameron Ray Morton (Prose) Alan Perry (Poetry) Trish Rodriguez (Prose) Kate Steagall (Prose) T. E. Wilderson (Prose) Associate Editors: Sally Badawi (Prose and Poetry) Charlotte Edwards (Prose) Teddy Engs (Prose) Jody Gerbig (Prose) Erin Karbuczky (Prose) Typehouse is a writer-run literary magazine based out of Portland, Oregon. We are always looking for well-crafted, previously unpublished writing and artwork that seeks to capture an awareness of the human condition. To learn more about us, visit our website at www.typehousemagazine.com. Cover Artwork: Jay and Turkey II, 24" x 36,” Acrylic on Canvas, from The Three Jay and Turkey Paintings by Elizabeth Eve King (E.E. King) (see page 49). Table of Contents Fiction: The Soap Carver Ryan Doskocil 2 Last Lost Boy Sara Herchenroether 14 Later Is One of Our Tags Jessica Evans 28 Nothing Ha-Ha Funny at the Edge of the Light Esem Junior 32 With Love, From Waystation 4 Brittany J. Smith 54 Zombie Kate Wendy Elizabeth Wallace 76 Lilac Boy Christopher Barker 81 That Changes Everything Naira Wilson 94 The Time Spider David Evan Krebs 104 Takahashi -

The Art of Being Human First Edition

The Art of Being Human First Edition Michael Wesch Michael Wesch Copyright © 2018 Michael Wesch Cover Design by Ashley Flowers All rights reserved. ISBN: 1724963678 ISBN-13: 978-1724963673 ii The Art of Being Human TO BABY GEORGE For reminding me that falling and failing is fun and fascinating. iii Michael Wesch iv The Art of Being Human FIRST EDITION The following chapters were written to accompany the free and open Introduction to Cultural Anthropology course available at ANTH101.com. This book is designed as a loose framework for more and better chapters in future editions. If you would like to share some work that you think would be appropriate for the book, please contact the author at [email protected]. v Michael Wesch vi The Art of Being Human Praise from students: "Coming into this class I was not all that thrilled. Leaving this class, I almost cried because I would miss it so much. Never in my life have I taken a class that helps you grow as much as I did in this class." "I learned more about everything and myself than in all my other courses combined." "I was concerned this class would be off-putting but I needed the hours. It changed my views drastically and made me think from a different point of view." "It really had opened my eyes in seeing the world and the people around me differently." "I enjoyed participating in all 10 challenges; they were true challenges for me and I am so thankful to have gone out of my comfort zone, tried something new, and found others in this world." "This class really pushed me outside my comfort