The Comic Way Towards the Universal Self: Socioecological Trauma and the Wounds Left by Survival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Bad Boy's Diary

mmY Frederick Warne and Co., Publisliers, NOTABLE NOVELS. COMFX.ETS EDITIONS. Large crown 8vo, SIXPENCE each, Picture Wrappers. 1 SCOTTISH CHIEFS. Miss JANB POET'EII. 2 UNCLB TOM'S CABIN". HABBIZT BjiECHIiB STOWE. 3 ST. CLAIK OF THE ISLES. ELIZABETH HELME. 4 CHILDEEW OF THE ABBEY. E. M. EocHE. 5 THE LAMPIiIGHTEE. Miss CUMMINS, 6 MABEL VAXJGHABT. Miss CUMMINS. 7 THADDEUS OF "WARSA-W. Miss PuRTER. 8 THE HOWARDS OF GLEN LUWA. Miss WARNER. 9 THE OLD ENGLISH BABON, &o. &<i. CLARA EEETE. 10 THE HUNGARIAN" BROTHERS. Miss POBTEE. 11 MARRIAGE. Miss FEKEIEE. 12 INHERITANCE. Miss FEBBIEE. 13 DESTINY. Miss FEBEIEB. 14 THE KING'S O-WN. Captain MAEETAT. 15 THE NAVAL OFFICER. Cai'tain MAEETAT. 16 NE-WTON FORSTER. Captain MABBTAT. 17 RICHELIEU. G, P, R. JAMES. 18 DARNLEY. G. P, E, JAMES. 19 PHILIP AUGUSTUS. G, P, E, JAMES. 20 TOM CRINGLE'S LOG. MICHAEL SOOTT. 21 PETER SIMPLE. Captain MARRTAT. 22 MARY OF BURGUNDY. G, P. E. JAMES. 23 JACOB FAITHFUL. Captain MAEETAT. 24 THE GIPSY. G. P, E, JAMES. 25 CRUISE OF THE MIDGE. MICHAEL SCOTT. 26 TWO YEARS BEFORE THE MAST. E. H. DANA. 27 THE PIRATE, AND THE THREE CUTTERS, Captain MAEETAT, 23 HENRY MASTERTON. G, P. E, JAMES. 29 JOHN MAESTON HALL. G, P, E. JAMES. 30 JAPHET IN SEARCH OF A FATHER. Captain MARBYAT. 31 THE •WOLF OF BADENOCH. Sir THOMAS DICK LAUDEK. 32 CALEB "WILLIAMS. WILLIAM Goowiif. 33 THE PACHA OF MANY TALES. Captain MAEETAT. 34 THE VICAR OF "WAKEFIEBD, OLITEE GoLDSMITn. 35 MR. MIDSHIPMAN EASY. Captain MARRTAT. 36 ATTILA. G. -

Volume I. Washington City, D. C., April 23, 1871. Number 7

<d VOLUME I. WASHINGTON CITY, D. C., APRIL 23, 1871. NUMBER 7. A HYMN TO THE TYPES. ing revolution of the earth, and hear the march bably; of my own age, though her self-pos- "In a month I set out for my trav&k. An- in the morning, there to nod in chairs by the the foot-lights shouting "fire! fire!" A terri- records, an order issued to the legation in Paris Mr. Babbitt observed that part of the leather W8S I BT CHAIUJEB'. O. KALPINE. of the moon in her attendant orbit. session might have stafliped her as much older; easy coach conveyed me to Londph, and the side of a bed-ridden mother, a widow whom ble uproar succeeded. The manager went when Mr. Polk was President, and Mr. Buchanan discolored ; and wheu he reached the boat, a t'h'éy supported oii their hard won pittance, Secretary of Stute, directing the minister to send darkly colored liquid was dripping from the sack. H O eiliinl. myriad army, whbse trae metal "My parents loved mfe tenderly, and, fail- but the bloom of her cheek, and her bosom just third day I lay sick in Paris. Sqr§ of Bftdy on tho stage and tried to quiet the alarmed such private letters as he might place in the dis- With lufinlte labor he Worked his dispatches • Ne'er flinched nor blenched before the despot Wrong! ing to soothe or conciliate me, they removed ripening, were indices of a girl's years. She and of brain, strained in nerve, and stunned fifty Cents, or at most a dollar a night. -

Rebecca Sugar Songs from Adventure Time & Steven

REBECCA SUGAR SONGS FROM ADVENTURE TIME & STEVEN UNIVERSE This book is a collection of ukulele tabs for songs by Rebecca Sugar from shows Adventure Time and Steven Universe. Tabs, lyrics, and background art by Rebecca Sugar. Rebecca Sugar is an American artist, composer, and director who is best known for being a writer and storyboard artist on Adventure Time as well as being the creator of Steven Universe. Material gathered and book designed by Angela Liu. Cover art and icons provided by Angela Liu. Made for Communication Design Fundamentals, 2015 (Carnemgie Mellon University). Table of Contents Adventure Time 4 - As a Tropical Island 6 - Oh Fionna 8 - My Best Friends in the World 10 - Remember You 12 - Good Little Girl Steven Universe 14 - Steven Universe Theme 16 - Be Wherever You Are As a Tropical Island Adventure Time / Season 3, Ep 2: Morituri Te Salutamux Air date: July 18, 2011 G C D7 G On a tropical island, on a tropical island. G C D7 G On a tropical island, on a tropical island! G C On a tropical island, D7 G Underneath a motlen lava moon. G C Hangin’ with the hoola dancers, D7 G Asking questions cause they got all the answers. G G Puttin’ on lotion, sitting by the ocean. C D7 Rubbin’ it on my body, rubbin’ it on my body. G G B7 Cmaj7 Get me out of this ca-a-ave, C7 G B7 Cmaj7 cause’ it’s nothin’ but a gladiator gra-a-ave. G G B7 Cmaj7 And if we stick to the pla-a-an, C7 G B7 Cmaj7 I think I’ll turn into a lava ma-a-an. -

I;' August. 1969

MARK TWAIN'S DEVELOPMENT OF THE NARRATIVE AND VERNACULAR PERSONA TECHNIQUE ,r~ ... : tI;' A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE KANSAS STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE OF EMPORIA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS POR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS By JAY H. BOYLAN .-/ August. 1969 111:' -< J J _ ! j/ Approved for the Major Department r I, itbo... .- Approved for the Graduate Council tf ~~ r)Q8.... ~:rL'09 "'0 .....,t) PREFACE Mark ~qain was such a dominant personality that he literally commanded the full attention of his day with his ac tivities. It has been said that he was the world's most well~known figure in his time. Twain's speaking tours in America and abroad helped him to create and maintain his image as a kind of representative American personality; in many ways he seemed the embodiment of the new man, the new spirit. After Twain's death in 1910, the force of his personality was so strong that it continued to overshadow his works. The early theories of Brooks' therefore were in the best traditions of biographical criticism and in the best traditions of Twain criticism; Brooks and others kept the emphasis on the man, Twain, rather than on his works. Brooks' idea, that Twain was a "divine amateur" who was thwarted by a psychological wound, is obviously in keeping with the forces of that time. What is not so obvious is tha.t Twain's supporters such as Devoto were, also, a part of this same tradition. Devoto defended Twain by trying to show from Twain's life that he was not psycho logically "wounded." The whole period of the 1920's and 1930's was an unfortunate one for Twain criticism because it was dominated by Mark Twain with a concomitant de-emphasis of his works and their merits. -

Rebecca Sugar Songs from Adventure Time & Steven

REBECCA SUGAR SONGS FROM ADVENTURE TIME & STEVEN UNIVERSE 1 Table of Contents Adventure Time 4 - As a Tropical Island 5 - Oh Fionna 6 - My Best Friends in the World 8 - Remember You 10 - All Gummed Up Inside 11 - Oh Bubblegum 12 - Good Little Girl Steven Universe 14 - Steven Universe Theme 15 - End Credits Song 16 - Drive My Van Into Your Heart 18 - Giant Woman 19 - Be Wherever You Are 20 - Strong in the Real Way This book is a collection of ukulele tabs for songs by Rebecca Sugar from shows Adventure Time and Steven Universe. Tabs, lyrics, and background art by Rebecca Sugar. Rebecca Sugar is an American artist, composer, and director who was a writer and storyboard artist on Adventure Time and is the creator of Steven Universe. Material gathered and book designed by Angela Liu. Cover art and icons provided by Angela Liu. Made for Communication Design Fundamentals, 2015. 2 3 As a Tropical Island Oh Fionna Adventure Time / Season 3, Ep 2: Morituri Te Salutamux Adventure Time / Season 3, Ep 9: Fionna and Cake Air date: July 18, 2011 Air date: September 5, 2011 G C D7 G C E7 Am On a tropical island, on a tropical island. I feel like nothing was real, until I met you. G C D7 G Dm G7 C G7 On a tropical island, on a tropical island! I feel like we connect, and I really get you. C E7 Am G C If I said “You’re a beautiful girl,” would it upset you? On a tropical island, Dm G7 D7 G Because the way you look tonight, Underneath a motlen lava moon. -

Commentary V2 Proofed FINAL

!1 Sonic autoethnographies: six | records | of | the | listening | self Iain Findlay-Walsh Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Music (Composition) School of Culture and Creative Arts College of Arts University of Glasgow February 2016 !2 Portfolio contents 1. Commentary (including portfolio on USB flash drive) 2. plastic 2 x CD case - corresponding to postface 3. 1 x CD wrapped in packing tape - corresponding to In Posterface: 1 4. 12” art print in PVC sleeve - corresponding to Somehere in 5. removable vinyl sticker - corresponding to _omiting in the changing room !3 Acknowledgements Thanks to Louisa-Jane, Blue and Bon Findlay-Walsh for providing the support and space to develop and complete this work. Thanks to Nick Fells and Martin Parker Dixon, who supervised throughout the project. Thanks to the following for supporting me in this work, providing opportunities to test and present parts of it, and contributing to the ideas and practice. Alasdair Campbell, Clare McFarlane, Tristan Partridge, John Campbell, May Campbell, Ruth Campbell, FK Alexander, Rob Alexander, Nick Anderson, Calum Beith, Rosana Cade, Liam Casey, Martin Cloonan, Lewis Cook, Carlo Cubero, Euan Currie, Anne Danielsen, Neil Davidson, Barry Esson, Stuart Evans, Paul Gallagher, Mark Grimshaw, Louise Harris, Paul Henry, Fielding Hope, Katia Isakoff, Bryony McIntyre, Emily McLaren, Jamie McNeill, Rickie McNeill, Felipe Otondo, Dale Perkins, Emily Roff, Calum Scott, Toby Seay, Sam Smith, Craig Tannoch, Rupert Till, Fritz Welch, Simon Zagorski-Thomas. !4 Abstract This commentary accompanies a portfolio of pieces which combine soundscape composition and record production methods with aspects of autoethnographic practice. This work constitutes embodied research into relations between everyday auditory experience, music production and reception, and selfhood. -

HECUBA by Euripides

HECUBA by Euripides translated by Jay Kardan and Laura-Gray Street POLYDORUS HECUBA CHORUS POLYXENA ODYSSEUS TALTHYBIUS THERAPAINA AGAMEMNON POLYMESTOR Script copyright Jay Kardan and Laura-Gray Street. Apply to the authors for performance permissions. Hecuba — translated by Kardan and Street — in Didaskalia 8 (2011) 32 POLYDORUS I come from bleakest darkness, where corpses lurk and Hades lives apart from other gods. I am Polydorus, youngest son of Hecuba and Priam. My father, worried Troy might fall to Greek offensives, sent me here, to Thrace, my mother’s father’s home and land of his friend Polymestor, who controls this rich plain of the Chersonese and its people with his spear. My father sent a large stash of gold with me, to insure that, if Ilium’s walls indeed (10) were toppled, I’d be provided for. He did all this because I was too young to wear armor, my arms too gangly to carry a lance. As long as the towers of Troy remained intact, and the stones that marked our boundaries stood upright, and my brother Hector was lucky with his spear, I thrived living here with my father’s Thracian friend, like some hapless sapling. (20) But once Troy was shattered—Hector dead, our home eviscerated, and my father himself slaughtered on Apollo’s altar by Achilles’ murderous son— then Polymester killed me. This “friend” tossed me dead into the ocean for the sake of gold, so he could keep Priam’s wealth for himself. My lifeless body washes ashore and washes back to sea with the waves’ endless ebb and flow, and remains unmourned, unburied. -

THE ATHEISM of MARK TWAIN: the EARLY YEARS THESIS Presented

37c A:) 2 THE ATHEISM OF MARK TWAIN: THE EARLY YEARS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Wesley Britton, B.A. Denton, Texas April, 1986 Britton, Wesley A. , The Atheism of Mark Twain: The Early Years. Master of Arts (English),, Augustj198 6 , 73 pp. , bibliography 26 titles. Many Twain scholars believe that his skepticism was based on personal tragedies of later years. Others find skepticism in Twain's work as early as The Innocents Abroad. This study determines that Twain's atheism is evident in his earliest writings. Chapter One examines what critics have determined Twain's religious sense to be. These contentions are dis- cussed in light of recent publications and older, often ignored, evidence of Twain' s atheism. Chapter Two is a biographical look at Twain's literary, family, and community influences, and at events in Twain's life to show that his religious antipathy began when he was quite young. Chapter Three examines Twain's early sketches and journalistic squibs to prove that his voice, storytelling techniques, subject matter, and antipathy towards the church and other institutions are clearly manifested in his early writings. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTIO. .... .. .. .. .. .. .. Chapter I. THE CRITICAL BACKGROUND . .. .. .. 7 ... .- .- .-- .- .* .- --26 II, BIOGRAPHY - III. THE EARLY WRITINGS . .44 CONCLUSION .. ,. 0. , . .. 09. .. ... 67 BIBLIOGRAPHY. .. .. .. .0. .a.071 INTRODUCTION The purpose of this study is to demonstrate that from a very early age, Samuel Langhorn Clemens had no strong religious convictions, and that, indeed, for most of his life, he was an atheist. -

Metonymy & Trauma

ii METONYMY & TRAUMA RE-PRESENTING DEATH IN THE LITERATURE OF W. G. S E B A L D Andrew Michael Watts A research dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD English University of New South Wales 2006 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: WATTS First name: ANDREW Other names: MICHAEL Abbreviation for degree as given in the University Calendar: PhD School: ENGLISH Faculty: ARTS Title: Metonymy & Trauma: Re-presenting Death in the Literature of W. G. Sebald Abstract 350 words maximim: (PLEASE TYPE) Novel: Fragments of a Former Moon The novel Fragments of a Former Moon (FFM) invokes the paradoxical earlier death of the still-living protagonist. The unmarried German woman is told that her skeletal remains have been discovered in Israel, thirty-eight years since her body was interred in 1967. This absurd premise raises issues of representing death in contemporary culture; death's destabilising effect on the individual's textual representation; post-Enlightenmentdissolution of the modern rational self; and problems of mimetic post- Holocaust representation. Using W G Sebald's fiction as a point of departure, FFM's photographic illustrations connote modes of textual representation that disrupt the autobiographical self, invoking mortality and its a-temporal (representational) displacement. As with Sebald's recurring references to the Holocaust, FFM depicts a psychologically unstable protagonist seeking to recover repressed memories of an absent past. Research dissertation: Metonymy &Trauma: Re-presenting Death in the Literature of W. G. Sebald The dissertation centres on the effect of metonymy in the rhetoric of textually-constructedidentity and its contemporary representation in the face of death. -

Adventure Time Princess Day Dvd

Adventure time princess day dvd click here to download Cartoon Network: Adventure Time - Princess Day (V7). Oh My GLOB! It's practically princess overload in Cartoon Networks latest release Adventure Time: Princess Day. Featuring fan favorite leading royal lady Lumpy Space Princess on the amaray, this is the 7th Adventure Time volume releasing with 16 full episodes. DVD Summary: Oh My GLOB! It's practically princess overload in Cartoon Networks latest release Adventure Time: Princess Day. Featuring fan favorite leading royal lady Lumpy Space Princess on the amaray, this is the 7th Adventure Time volume releasing with 16 full episodes. Adventure Time: Princess Day releases just. Even though it is Princess Day, not every princess in the series appeared in the episode. This episode was released on DVD before it aired on TV. Marceline is shown holding a bottle of sunscreen in the promotional artwork and in her first appearance in the episode, which explains why she was unharmed in the morning. Oh My Glob! So. Many. Princesses!!! Check out this royalty-filled clip from the all-new Princess Day episode. Princess Day” is a fun episode, but it's especially notable for two specific reasons. To start, the episode was released on home video two days ago as part of a DVD compilation, the first time Cartoon Network has released an episode on video before airing it. It's also the first episode—not including the. Cartoon Network is at it again with another cartoon collection aimed at undiscerning fans who NEED some episodes NOW and are not concerned about bonus features and complete season sets and story continuity. -

Volume 8, No. 2 Issue 22

Volume 8, No. 2 Issue 22 ©2021 Typehouse Literary Magazine. All rights reserved. No part of this periodical may be reproduced in any form without written permission. Typehouse Literary Magazine is published triannually. Established 2013. Typehouse Literary Magazine Editor in Chief: Val Gryphin Senior Editors: Nadia Benjelloun (Prose) Lily Blackburn (Craft Essay) Jiwon Choi (Poetry) Mariya Khan (Prose and Poetry) Yukyan Lam (Prose) Jared Linder (Prose) Kameron Ray Morton (Prose) Alan Perry (Poetry) Trish Rodriguez (Prose) Kate Steagall (Prose) T. E. Wilderson (Prose) Associate Editors: Sally Badawi (Prose and Poetry) Charlotte Edwards (Prose) Teddy Engs (Prose) Jody Gerbig (Prose) Erin Karbuczky (Prose) Typehouse is a writer-run literary magazine based out of Portland, Oregon. We are always looking for well-crafted, previously unpublished writing and artwork that seeks to capture an awareness of the human condition. To learn more about us, visit our website at www.typehousemagazine.com. Cover Artwork: Jay and Turkey II, 24" x 36,” Acrylic on Canvas, from The Three Jay and Turkey Paintings by Elizabeth Eve King (E.E. King) (see page 49). Table of Contents Fiction: The Soap Carver Ryan Doskocil 2 Last Lost Boy Sara Herchenroether 14 Later Is One of Our Tags Jessica Evans 28 Nothing Ha-Ha Funny at the Edge of the Light Esem Junior 32 With Love, From Waystation 4 Brittany J. Smith 54 Zombie Kate Wendy Elizabeth Wallace 76 Lilac Boy Christopher Barker 81 That Changes Everything Naira Wilson 94 The Time Spider David Evan Krebs 104 Takahashi -

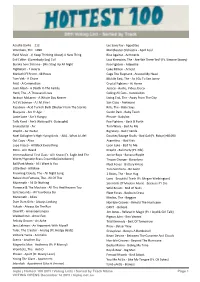

Triple J Hottest 100 2011 | Voting Lists | Sorted by Track Name Page 1 VOTING OPENS December 14 2011 | Triplej.Net.Au

Azealia Banks - 212 Les Savy Fav - Appetites Wombats, The - 1996 Manchester Orchestra - April Fool Field Music - (I Keep Thinking About) A New Thing Rise Against - Architects Evil Eddie - (Somebody Say) Evil Last Kinection, The - Are We There Yet? {Ft. Simone Stacey} Buraka Som Sistema - (We Stay) Up All Night Foo Fighters - Arlandria Digitalism - 2 Hearts Luke Million - Arnold Mariachi El Bronx - 48 Roses Cage The Elephant - Around My Head Tom Vek - A Chore Middle East, The - As I Go To See Janey Feist - A Commotion Crystal Fighters - At Home Juan Alban - A Death In The Family Justice - Audio, Video, Disco Herd, The - A Thousand Lives Calling All Cars - Autobiotics Jackson McLaren - A Whole Day Nearer Living End, The - Away From The City Art Vs Science - A.I.M. Fire! San Cisco - Awkward Kasabian - Acid Turkish Bath (Shelter From The Storm) Kills, The - Baby Says Bluejuice - Act Yr Age Caitlin Park - Baby Teeth Lanie Lane - Ain't Hungry Phrase - Babylon Talib Kweli - Ain't Waiting {Ft. Outasight} Foo Fighters - Back & Forth Snakadaktal - Air Tom Waits - Bad As Me Drapht - Air Guitar Big Scary - Bad Friends Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds - AKA…What A Life! Douster/Savage Skulls - Bad Gal {Ft. Robyn}+B1090 Cut Copy - Alisa Argentina - Bad Kids Lupe Fiasco - All Black Everything Loon Lake - Bad To Me Mitzi - All I Heard Drapht - Bali Party {Ft. Nfa} Intermashional First Class - All I Know {Ft. Eagle And The Junior Boys - Banana Ripple Worm/Hypnotic Brass Ensemble/Juiceboxxx} Tinpan Orange - Barcelona Ball Park Music - All I Want Is You Fleet Foxes - Battery Kinzie Little Red - All Mine Tara Simmons - Be Gone Frowning Clouds, The - All Night Long 2 Bears, The - Bear Hug Naked And Famous, The - All Of This Lanu - Beautiful Trash {Ft.